|

Red Terror

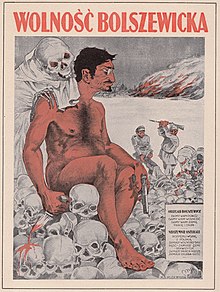

The Red Terror (Russian: красный террор, romanized: krasnyy terror) was a campaign of political repression and executions in Soviet Russia carried out by the Bolsheviks, chiefly through the Cheka, the Bolshevik secret police. It officially started in early September 1918 and lasted until 1922.[4][5] Arising after assassination attempts on Vladimir Lenin along with the successful assassinations of Petrograd Cheka leader Moisei Uritsky and party editor V. Volodarsky[6] in alleged retaliation for Bolshevik mass repressions, the Red Terror was modeled on the Reign of Terror of the French Revolution,[7] and sought to eliminate political dissent, opposition, and any other threat to Bolshevik power.[8][better source needed] More broadly, the term can be applied to Bolshevik political repression throughout the Russian Civil War (1917–1922).[9][10][11] Bolshevik leaders attempted to excuse the severe repression as a necessary response to the White Terror initiated in 1917. HistoryBackgroundWhen the Revolution took power in November 1917, many top Bolsheviks hoped to avoid much of the violence which would come to define this period.[12] Through one of its first decrees on 8 November 1917, the Second All-Russian Congress of Soviets of Workers' and Soldiers' Deputies abolished the death penalty. It had first been canceled by the February Revolution and then restored by the Kerensky's government. Not a single death sentence was issued in the first three months of Lenin's government,[6] which consisted in fact of a coalition with the Left Socialist-Revolutionaries, who, albeit terrorists in the tsarist era, were staunch opponents of the death penalty. However, as pressure mounted from the White Armies and from international intervention, the Bolsheviks moved closer to Lenin's harsher perspective. The decision to enact the Red Terror was also driven by the initial "massacre of their 'Red' prisoners by the office-cadres during the Moscow insurrection of October 1917", allied intervention in the Russian Civil War, and the large-scale massacres of Reds during the Finnish Civil War in which 10,000 to 20,000 revolutionaries had been killed by the Finnish Whites.[6] In December 1917, Felix Dzerzhinsky was appointed to the duty of rooting out counterrevolutionary threats to the Soviet government. He was the director of the All-Russian Extraordinary Commission (aka Cheka), a predecessor of the KGB that served as the secret police for the Soviets.[13] From spring 1918, the Bolsheviks started physical elimination of opposition and other socialist and revolutionary factions, anarchists among the first, according to the anarchist activists Alexander Berkman and Emma Goldman:

On 21 February 1918, the death penalty was also formally re-established, as an exceptional revolutionary instrument, with the famous decree Socialist Homeland is in Danger!.[15] In article 8, it read as follows: "Enemy agents, profiteers, marauders, hooligans, counter-revolutionary agitators and German spies are to be shot on the spot".[16] The first and second pages of the so-called "Lenin's Hanging Order" concerning a peasant revolt in Penza governorate; the "order" was not carried out as such On 16 June, more than two months prior to the events that would officially catalyze the Terror, a new decree re-established the death penalty as an ordinary jurisdictional measure by instructing the Revolutionary People's Courts to use it "as the only punishment for counter-revolutionary offences".[15] Prior to the events that would officially catalyze the Terror,[11] Lenin issued orders and made speeches which included harsh expressions and descriptions of brutal measures to be taken against the "class enemies", which, however, often were not actual orders or were not carried out as such.[17] For example, in a telegram, which became known as "Lenin's hanging order", he demanded to "crush" landowners in Penza and to publicly hang "at least 100 kulaks, rich bastards, and known bloodsuckers"[11] in response to a peasant revolt there; yet, only the 13 organizers of the murder of local authorities and the uprising were arrested, while the uprising was ended with a number of propaganda activities;[17] in 1920, having received information that in Estonia and Latvia, with which Soviet Russia had concluded peace treaties, volunteers were being enrolled in anti-Bolshevik detachments, Lenin offered to "advance by 10–20 miles (versts) and hang kulaks, priests, landowners" "while pretending to be greens",[18] but instead, Lenin's government confined itself to sending diplomatic notes; Lenin even urged to "hang" Anatoly Lunacharsky and "Communist scum". Russian historian Vladlen Loginov explains that while relatively peaceful resolutions of conflicts following Lenin's brutal declarations and "harsh words" and "orders" offering hard measures took place "not always and not everywhere", Lenin complained in his letters that[17] his bureaucratic "apparatus has already become gigantic — in some places excessively so — and under such conditions a “personal dictatorship” is entirely unrealizable and attempts to realize it would only be harmful."[19] Loginov explains that Lenin attempted to compensate this "lack of real power" with either with "abundance of decrees" or "simply with strong words."[17] Lenin had justified the state response to the kulak revolts due to the preceding 258 uprisings that had occurred in 1918 and the threat of the White Terror. He summarised his view that either the "kulaks massacre vast numbers of workers, or the workers ruthlessly suppress the revolt of the predatory kulak minority... There can be no middle course".[20] Beginnings Leonid Kannegisser, a young military cadet of the Imperial Russian Army, assassinated Moisey Uritsky on August 17, 1918, outside the Petrograd Cheka headquarters in retaliation for the execution of his friend and other officers.[21] On August 30, Socialist Revolutionary Fanny Kaplan unsuccessfully attempted to assassinate Vladimir Lenin.[7][13] During interrogation by the Cheka, she made the following statement:

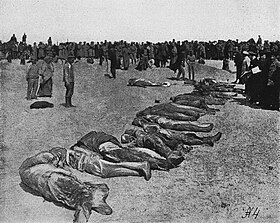

Kaplan referenced the Bolsheviks' growing authoritarianism, citing their forcible shutdown of the Constituent Assembly in January 1918, the elections to which they had lost. When it became clear that Kaplan would not implicate any accomplices, she was executed in Alexander Garden, near the western walls of the Kremlin. "Most sources indicate that Kaplan was executed on 3 September, the day after her transfer to the Kremlin". In 1958 the commander of the Kremlin, the former Baltic sailor Pavel Dmitriyevich Malkov (1887–1965)[23] revealed he had personally executed Kaplan on that date upon the specific orders of Yakov Sverdlov, chief secretary of the Bolshevik Central Committee.[24]: 442 She was killed with a bullet to the back of the head.[25] Her corpse was bundled into a barrel and set alight so that her "remains [might] be destroyed without a trace", as Sverdlov had instructed.[26] These events persuaded the government to heed Dzerzhinsky's lobbying for greater terror against opposition. The campaign of mass repressions would officially begin thereafter.[7][13] The Red Terror is considered to have officially begun between 17 and 30 August 1918.[7][13] Implementation     While recovering from his wounds, Lenin instructed: "It is necessary – secretly and urgently to prepare the terror."[27] In immediate response to the two attacks, Chekists killed approximately 1,300 "bourgeois hostages" held in Petrograd and Kronstadt prisons.[28] Bolshevik newspapers were especially integral to instigating an escalation in state violence: on August 31, the state-controlled media launched the repressive campaign through incitement of violence. One article appearing in Pravda exclaimed: "the time has come for us to crush the bourgeoisie or be crushed by it.... The anthem of the working class will be a song of hatred and revenge!"[13] The next day, the newspaper Krasnaia Gazeta stated that "only rivers of blood can atone for the blood of Lenin and Uritsky."[13] The first official announcement of a Red Terror was published in Izvestia on September 3, titled "Appeal to the Working Class": it had been drafted by Dzerzhinsky and his assistant Jēkabs Peterss and called for the workers to "crush the hydra of counter-revolution with massive terror!"; it would also make clear that "anyone who dares to spread the slightest rumor against the Soviet regime will be arrested immediately and sent to a concentration camp".[29] Izvestia also reported that, in the 4 days since the attempt on Lenin, over 500 hostages had been executed in Petrograd alone.[13] Subsequently, on September 5, the Council of People's Commissars issued a decree "On Red Terror", prescribing "mass shooting" to be "inflicted without hesitation;" the decree ordered the Cheka "to secure the Soviet Republic from the class enemies by isolating them in concentration camps", as well as stating that counter-revolutionaries "must be executed by shooting [and] that the names of the executed and the reasons of the execution must be made public."[13][30][31] According to official numbers, the Bolsheviks executed 500 "representatives of overthrown classes" (kulaks) immediately after the assassination of Uritsky.[32] Soviet commissar Grigory Petrovsky called for an expansion of the Terror and an "immediate end of looseness and tenderness."[8] In October 1918, Cheka commander Martin Latsis likened the Red Terror to a class war, explaining that "we are destroying the bourgeoisie as a class."[8] On October 15, the leading Chekist Gleb Bokii, summing up the officially-ended Red Terror, reported that, in Petrograd, 800 alleged enemies had been shot and another 6,229 imprisoned.[27] Casualties in the first two months were between 10,000 and 15,000 based on lists of summarily executed people published in newspaper Cheka Weekly and other official press. A declaration About the Red Terror by the Sovnarkom on 5 September 1918 stated:

As the Russian Civil War progressed, significant numbers of prisoners, suspects and hostages were executed because they belonged to the "possessing classes". Numbers are recorded for cities occupied by the Bolsheviks:

In Crimea, Béla Kun and Rosalia Zemlyachka, with Vladimir Lenin's approval,[35] had 50,000 White prisoners of war and civilians summarily executed by shooting or hanging after the defeat of general Pyotr Wrangel at the end of 1920. They had been promised amnesty if they would surrender.[36] This is one of the largest massacres in the Civil War.[37][13] The figures related to the massacre in Crimea remain contested. Anarchist and Bolshevik Victor Serge gave a lower figure for White officers around 13,000 which he claims were exaggerated. Yet, he condemned Kun for his treacherous actions towards allied anarchists and surrendering whites.[38] According to social scientist, Nikolay Zayats, from the National Academy of Sciences of Belarus the large, “fantastic” estimates derived from eyewitness accounts and White army emigre press. A Crimean Cheka report in 1921 showed that 441 people were shot with a modern estimation that 5,000–12,000 people in total were executed in Crimea.[39] At the same time, Lenin took measures even at the peak of the civil war to prevent the abuse of power by the Cheka. The case of Mrs. Pershikova may be symbolic: in 1919, she was arrested for defacing a picture-portrait of Lenin, but Lenin ordered to liberate her:[19]

On 16 March 1919, all military detachments of the Cheka were combined in a single body, the Troops for the Internal Defense of the Republic (a branch of the Cheka), which numbered at least 200,000 in 1921. These troops policed labor camps, ran the Gulag system, conducted prodrazverstka (requisitions of food from peasants), and put down peasant rebellions, riots by workers, and mutinies in the Red Army (which was plagued by desertions).[11] One of the main organizers of the Red Terror for the Bolshevik government was 2nd-Grade Army Commissar Yan Karlovich Berzin (1889–1938), whose real name was Pēteris Ķuzis. He took part in the October Revolution of 1917 and afterwards worked in the central apparatus of the Cheka. During the Red Terror, Berzin initiated the system of taking and shooting hostages to stop desertions and other "acts of disloyalty and sabotage".[40][page needed] As chief of a special department of the Latvian Red Army (later the Russian 15th Army), Berzin played a part in the suppression of the Red sailors' uprising at Kronstadt in March 1921. He particularly distinguished himself in the course of the pursuit, capture, and killing of captured sailors.[40][page needed] Affected groups Among the victims of the Red Terror were tsarists, liberals, non-Bolshevik socialists, anarchists, members of the clergy, ordinary criminals, counter-revolutionaries, and other political dissidents. Later, industrial workers who failed to meet production quotas were also targeted.[8] The first victims of the Terror were the Socialist Revolutionaries (SR). Over the months of the campaign, over 800 SR members were executed, while thousands more were driven into exile or detained in labor camps.[8] In a matter of weeks, executions carried out by the Cheka doubled or tripled the number of death sentences pronounced by the Russian Empire over the 92-year period from 1825 to 1917.[28] While the Socialist Revolutionaries were initially the primary targets of the terror, most of its direct victims were associated with the preceding regimes.[41][13] Peasants The Bolsheviks promised: We'll give you peace We'll give you freedom We'll give you land Work and bread Despicably they cheated They started a war With Poland Instead of freedom they brought The fist Instead of land – confiscation Instead of work – misery Instead of bread – famine. The Internal Troops of the Cheka and the Red Army practiced the terror tactics of taking and executing numerous hostages, often in connection with desertions of forcefully mobilized peasants. According to Orlando Figes, more than 1 million people deserted from the Red Army in 1918, around 2 million people deserted in 1919, and almost 4 million deserters escaped from the Red Army in 1921.[42] Around 500,000 deserters were arrested in 1919 and close to 800,000 in 1920 by Cheka troops and special divisions created to combat desertions.[11] Thousands of deserters were killed, and their families were often taken hostage. According to Lenin's instructions,

In September 1918, in just twelve provinces of Russia, 48,735 deserters and 7,325 brigands were arrested: 1,826 were executed and 2,230 were deported. A typical report from a Cheka department stated:

Estimates suggest that during the suppression of the Tambov Rebellion of 1920–1921, around 100,000 peasant rebels and their families were imprisoned or deported and perhaps 15,000 executed.[44] During the rebellion, Mikhail Tukhachevsky (chief Red Army commander in the area) authorized Bolshevik military forces to use chemical weapons against villages with civilian population and rebels.[45] Publications in local Communist newspapers openly glorified liquidations of "bandits" with the poison gas.[46] This campaign marked the beginning of the Gulag, and some scholars have estimated that 70,000 were imprisoned by September 1921 (this number excludes those in several camps in regions that were in revolt, such as Tambov). Conditions in these camps led to high mortality rates, and "repeated massacres" took place. The Cheka at the Kholmogory camp adopted the practice of drowning bound prisoners in the nearby Dvina river.[47] Occasionally, entire prisons were "emptied" of inmates via mass shootings prior to abandoning a town to White forces.[48][49] Industrial workersOn 16 March 1919, Cheka stormed the Putilov factory. Hundreds of workers who went to a strike were arrested, of whom around 200 were executed without trial during the next few days.[50][51] Numerous strikes took place in the spring of 1919 in cities of Tula, Oryol, Tver, Ivanovo, and Astrakhan. Starving workers sought to obtain food rations matching those of Red Army soldiers. They also demanded the elimination of privileges for Bolsheviks, freedom of the press, and free elections. The Cheka mercilessly suppressed all strikes, using arrests and executions.[52] In the city of Astrakhan, a revolt led by the White Guard forces broke out. In preparing this revolt, the Whites managed to smuggle more than 3000 rifles and machine guns into the city. The leaders of the plot decided to act on the night 9–10 March 1919. The rebels were joined by wealthy peasants from the villages, which suppressed the Committees of the Poor, and committed massacres against rural activists. Eyewitnesses reported atrocities in villages such as Ivanchug, Chagan, Karalat. In response, Soviet forces led by Kirov undertook to suppress this revolt in the villages, and together with the Committees of the Poor restored Soviet power. The revolt in Astrakhan was brought under control by 10 March, and completely defeated by the 12th. More than 184 were sentenced to death, including monarchists, and representatives of the Kadets, Left-Socialist Revolutionaries, repeat offenders, and persons shown to have links with British and American intelligence services.[53] The opposition media with political opponents like Chernov, and Melgunov, and others would later say that between 2,000 and 4,000 were shot or drowned from 12 to 14 of March 1919.[54] [55] However, strikes continued. Lenin had concerns about the tense situation regarding workers in the Ural region. On 29 January 1920, he sent a telegram to Vladimir Smirnov stating "I am surprised that you are putting up with this and do not punish sabotage with shooting; also the delay over the transfer here of locomotives is likewise manifest sabotage; please take the most resolute measures."[56] At these times, there were numerous reports that Cheka interrogators used torture. At Odessa, the Cheka tied White officers to planks and slowly fed them into furnaces or tanks of boiling water; in Kharkiv, scalpings and hand-flayings were commonplace: the skin was peeled off victims' hands to produce "gloves";[57] the Voronezh Cheka rolled naked people around in barrels studded internally with nails; victims were crucified or stoned to death at Yekaterinoslav; the Cheka at Kremenchuk impaled members of the clergy and buried alive rebelling peasants; in Oryol, water was poured on naked prisoners bound in the winter streets until they became living ice statues; in Kiev, Chinese Cheka detachments placed rats in iron tubes sealed at one end with wire netting and the other placed against the body of a prisoner, with the tubes being heated until the rats gnawed through the victim's body in an effort to escape.[58] Executions took place in prison cellars or courtyards, or occasionally on the outskirts of town, during the Red Terror and Russian Civil War. After the condemned were stripped of their clothing and other belongings, which were shared among the Cheka executioners, they were either machine-gunned in batches or dispatched individually with a revolver. Those killed in prison were usually shot in the back of the neck as they entered the execution cellar, which became littered with corpses and soaked with blood. Victims killed outside the town were moved by truck, bound and gagged, to their place of execution, where they sometimes were made to dig their own graves.[59] According to Edvard Radzinsky, "it became a common practice to take a husband hostage and wait for his wife to come and purchase his life with her body".[32] During decossackization, there were massacres, according to historian Robert Gellately, "on an unheard of scale". The Pyatigorsk Cheka organized a "day of Red Terror" to execute 300 people in one day, and took quotas from each part of town. According to the Chekist Karl Lander, the Cheka in Kislovodsk, "for lack of a better idea", killed all the patients in the hospital. In October 1920 alone more than 6,000 people were executed. Gellately adds that Communist leaders "sought to justify their ethnic-based massacres by incorporating them into the rubric of the 'class struggle'".[60] Clergy Members of the clergy were subjected to particularly brutal abuse. According to documents cited by Alexander Yakovlev, then head of the Presidential Committee for the Rehabilitation of Victims of Political Repression, priests, monks and nuns were crucified, thrown into cauldrons of boiling tar, scalped, strangled, given Communion with melted lead and drowned in holes in the ice.[61] An estimated 3,000 were put to death in 1918 alone.[61] Number of deathsThere is no consensus among the Western historians on the number of deaths from the Red Terror. James Ryan writes that there were "at lowest estimates" "on average" 28,000 executions per year from December 1917 to February 1922.,[62] and that the number of people shot during the initial period of the Red Terror is at least 10,000.[41] Estimates for the whole period range from of 50,000[63] executions to an upper of 140,000[63][64] to 200,000 people (plus an additional 400,000 killed in prisons or in suppressions of local rebellions[1] - the latter (highest) figures were presented by Robert Conquest. The lowest among the estimates "of those who died at the hands of the Soviet government" cited by Evan Mawdsley is a figure of 12,733 executed by the Cheka between 1917 and 1920 as estimated by Martin Latsis; Mawdsley writes that "Latsis's figures seem too low, and Conquest's too high, but one can only guess", implying the figures of 50,000 victims presented by William Henry Chamberlin and 140,000 victims presented by George Leggett to be more plausible.[65] Ronald Hingley wrote that Chamberlin's estimate "must be nearer the truth" than "1,700,000, which appears to be a considerable exaggeration."[3] Some contemporary historians present figures exceeding a million of victims: Dietrich Beyrau believes the number of victims of the Red Terror to be "up to 1.3 millions" compared to between 20,000 and 100,000 of the White Terror,[66] while a Russian historian V. Erlikhman, whose estimates are cited by Jonathan D. Smele, presents the figure of 1,200,000 deaths caused by the Red Terror compared to 300,000 victims of the White Terror.[67] In 1924, Popular Socialist, Sergei Melgunov (1879–1956), published a detailed account on the Red Terror in Russia, where he cited Professor Charles Saroléa's counts of 1,766,188 executions. He questioned the accuracy of the figures, but endorsed Saroléa's "characterisation of terror in Russia", stating it "in general matches reality".[68][b] Other sources have also characterized the widely circulated claim of 1,700,000 deaths to be a "wild exaggeration" and placed estimations closer to 50,000 over the three year Civil War period.[70] British historian Ronald Hingley attributed the exaggerated claim of 1,700,000 to a quoted statement from White Army leader Anton Denikin.[3] However, according to historian W. Bruce Lincoln (1989), the best estimations for the number of executions in total put the number at about 100,000.[71] According to Robert Conquest, a total of 140,000 people were shot in 1917–1922, but Jonathan D. Smele estimates they were considerably fewer, "perhaps less than half that many".[72] According to others, the number of people shot by the Cheka in 1918–1922 is about 37,300 people, shot in 1918–1921 by the verdicts of the tribunals – 14,200, although executions and atrocities were not limited to the Cheka, having been organized by the Red Army as well.[39][73] Justification by Bolsheviks

The Red Terror in Soviet Russia was justified in Soviet historiography as a wartime campaign against counter-revolutionaries during the Russian Civil War of 1918–1922, targeting those who sided with the Whites (White Army). In his book, Terrorism and Communism: A Reply to Karl Kautsky, Trotsky also argued that the reign of terror began with the White Terror under the White Guard forces and the Bolsheviks responded with the Red Terror.[74] Kautsky pleaded with Lenin against using violence as a form of terrorism because it was indiscriminate, intended to frighten the civilian population and included the taking and executing hostages: "Among the phenomena for which Bolshevism has been responsible, terrorism, which begins with the abolition of every form of freedom of the Press, and ends in a system of wholesale execution, is certainly the most striking and the most repellent of all."[75] Martin Latsis, chief of the Ukrainian Cheka, stated in the newspaper Krasny Terror (Red Terror):

Lenin in response mildly criticized Latsis' determination:

The Red Terror was described succinctly from the Bolshevik point of view by Grigory Zinoviev in mid-September 1918:

From an opposite point of view to the Bolsheviks', in November 1918, Left Socialist Revolutionary leader Maria Spiridonova, while being in prison and awaiting trial, condemned the Red Terror in her Open Letter to the Central Executive of the Bolshevik party. She wrote:

Interpretations by historiansHistorians such as Stéphane Courtois and Richard Pipes have argued that the Bolsheviks needed to use terror to stay in power because they lacked popular support;[11][79] Pipes is a representative of 'neo-traditionalist' historians who oppose 'revisionists', who put an emphasis on the 'popular' nature of the Bolshevik Revolution, and follow 'totalitarian' approach which continued the 'traditionalist' approach which dominated during the Cold War; for 'traditionalists' and 'neo-traditionalists', the Revolution was something imposed 'from above' by the revolutionaries with political guile and brute force.[65] Although the Bolsheviks dominated among workers, soldiers and in their revolutionary soviets, they won less than a quarter of the popular vote in elections for the Constituent Assembly held soon after the October Revolution, since they commanded much less support among the peasantry. The Constituent Assembly elections predated the split between the Right SRs, who had opposed the Bolsheviks, and the Left SRs, who were their coalition partners, consequentially many peasant votes intended for the latter went to the SRs.[80][81][82] Massive strikes by Russian workers were "mercilessly" suppressed during the Red Terror.[80] According to Pipes, terror was inevitably justified by Lenin's belief that human lives were expendable in the cause of building the new order of communism. Pipes has quoted Marx's observation of the class struggles in 19th-century France: "The present generation resembles the Jews whom Moses led through the wilderness. It must not only conquer a new world, it must also perish in order to make room for the people who are fit for a new world"; yet, Pipes noted that neither Karl Marx nor Friedrich Engels encouraged mass murder.[79][83] Eric Hobsbawm, despite his sympathy for the October Revolution and Communist movements, also recognized Lenin's beliefs, like his view of political struggle as a total war and a zero-sum game, as one of the reasons of the Red Terror and the mass violence carried out by the Bolsheviks, although he writes that "it was not so much the belief that a great end justifies all the means necessary to achieve it..., or even the belief that the sacrifices imposed on the present generation, however large, are as nothing to the benefits which will be reaped by the endless generations of the future", but "the application of the principle of total war to all times. Leninism, perhaps because of the powerful strain of voluntarism which made other Marxists distrust Lenin as a 'Blanquist' or 'Jacobin,' thought essentially in military terms, as his own admiration for Clausewitz would indicate, even if the entire vocabulary of Bolshevik politics did not bear witness to it."[84] Orlando Figes' view was that Red Terror was implicit, not so much in Marxism itself, but in the tumultuous violence of the Russian Revolution. He noted that there were a number of Bolsheviks, led by Lev Kamenev, Nikolai Bukharin, and Mikhail Olminsky, who criticized the actions and warned that thanks to "Lenin's violent seizure of power and his rejection of democracy," the Bolsheviks would be "forced to turn increasingly to terror to silence their political critics and subjugate a society they could not control by other means."[85] Figes also asserts that the Red Terror "erupted from below. It was an integral element of the social revolution from the start. The Bolsheviks encouraged but did not create this mass terror. The main institutions of the Terror were all shaped, at least in part, in response to these pressures from below."[86] The Hungarian historian Tamás Krausz supports the view that terror was rather a result of objective processes, and notes that Lenin, as Trotsky wrote earlier, formed his more differentiated position regarding terror over a period of years, and in the period of the First Russian Revolution, Lenin objected terror as a means of "expropriating private property", since the revolutionary forces were not at war with individuals, but with the system, and viewed terror only as a secondary tool of countering state violence in the moments of revolutionary upheaval, and in 1907, the Bolsheviks accepted a resolution which denounced terror and rejected it as a method in advance; Krausz writes that terror was not something rooted in revolutionary theory, but a result of a combination of Russian traditions of political violence with the cult of violence brought by World War I and the escalation of struggle into a civil war, in which both sides sought to annihilate each other, and likely with Mikhail Bakunin's idea of a "collective Razin" embodied both in the popular rebellion and in the popular leader "at the head of the masses", a concept spread among Russian revolutionaries, and the Marxist concept of 'dictatorship of proletariat'; Lenin also drew the idea of a necessity of terror from his reading of the histories of the French Revolution and American Civil War.[19] Leszek Kołakowski wrote that while Bolsheviks (especially Lenin) were very much focused on the Marxian concept of "violent revolution" and dictatorship of the proletariat long before the October Revolution, implementation of the dictatorship was clearly defined by Lenin as early as in 1906, when he argued it must involve "unlimited power based on force and not on law," power that is "absolutely unrestricted by any rules whatever and based directly on violence." In The State and Revolution of 1917, Lenin once again reiterated the arguments raised by Marx and Engels calling for use of terror. Voices such as Kautsky calling for moderate use of violence met "furious reply" from Lenin in The Proletarian Revolution and the Renegade Kautsky (1918). Another theoretical and systematic argument in favor of organized terror in response to Kautsky's reservations was written by Trotsky in The Defense of Terrorism (1921). Trotsky argued that in the light of historical materialism, it is sufficient that the violence is successful for it to justify its rightness. Trotsky also introduced and provided ideological justification for many of the future features characterizing the Bolshevik system such as "militarization of labor" and concentration camps.[87] A number of historians, such as Pipes and Nicolas Werth (The Black Book of Communism), contrasted the Red and White Terrors, claiming that while Red Terror was a political strategy and a "revolutionary" means of reconstructing the world, ideological and instrumental, the White Terror was restorative, arbitrary and a temporary measure, mere "repressive violence" to re-establish a previous status quo.[84][88] Robert Conquest was convinced that "unprecedented terror must seem necessary to ideologically motivated attempts to transform society massively and speedily, against its natural possibilities",[80] while Werth wrote:

Such notion is refuted by Peter Holquist and Joshua Sanborn.[84] Holquist wrote that "White violence may have been less centralized and systematic, but it did not lack ideological underpinnings. [...] It is hard to imagine that the massacre of tens of thousands of Jews by the anti-Soviet armies during the civil wars... could have occurred without some form of ideology – and particularly the virulent linkage drawn between Jews and Communists."[88] According to Sanborn, the terror carried out by the Russian Imperial Army and the Whites was as 'revolutionary' as their Red counterpart:[84]

James Ryan claims that Lenin never advocated for the physical extermination of the entire bourgeoisie as a class, just the execution of those who were actively involved in opposing and undermining Bolshevik rule.[90] He did intend to bring about "the overthrow and complete abolition of the bourgeoisie" through non-violent political and economic means, but he also noted that in reality the period of transition from capitalism to communism 'is a period of un unprecedentedly violent class struggle in unprecedentedly acute forms, and, consequently, during this period the state must inevitably be a state that is democratic in a new way (for the proletariat and propertyless in general) and dictatorial in a new way (against the bourgeoise)'.[91] Historical significance  The Red Terror was significant because it was the first of numerous communist terror campaigns which were waged in Soviet Russia and many other countries.[92][page needed] It also triggered the Russian Civil War according to historian Richard Pipes.[79] Menshevik Julius Martov wrote about the Red Terror:

The term "Red Terror" was later used in reference to other campaigns of violence which were waged by communist or communist-affiliated groups. Some other events which were also called "Red Terrors" include:

See also

Notes

References

Bibliography and further readingSee also: Bibliography of the Russian Revolution and Civil War § Violence and terror

External links

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||