|

Portraits of Wolfgang Amadeus MozartNumerous historical paintings and other works of art purport to depict the composer Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart. Of these, only a fraction can be shown by historical evidence to be authentic portrayals. They exist amid a great number of inauthentic ones, which are either fraudulent or else sentimental works of the imagination. Of the authentic portraits, the posthumous 1819 painting by Barbara Krafft is the best known. The task of distinguishing authentic from inauthentic portraits has occupied Mozart scholars for many years. BackgroundA few portraits of Mozart were made during his lifetime, but most were realised after his death, as his fame spread. According to Robert Bory, 62 portraits of Mozart and pictorial representations of all kinds exist;[1] but they vary widely in size, support, media used, style and degree of fidelity. Mozart experts who have examined the portraits, such as Arthur Hutchings, Arthur Schurig, Martin Braun and Alfred Einstein, emphasize the contrast between the sheer number of artworks that purport to represent Mozart and their sparse iconographic value.[2] Schurig wrote in 1913: "Mozart has been the subject of more portraits quite unrelated to his actual appearance than any other famous man. An adoring posterity has not conceived a more incorrect physical image of any other notability."[3] Such views arise from the analysis of the existing paintings, miniatures, sketches, drawings, cameos, and engravings of the composer. Julius Leisching[4] and Max Zenger[5] made a first selection and Otto Erich Deutsch established a list of the authentic portraits and the forgeries, mostly from the 19th century.[6] The conclusion of this work is that only eight works of art,[3] of unequal interest, were produced by authors who knew Mozart directly, or by sketches taken from drawings made from life. Since then, Mozart's "biographical paintings" have been published with more care, generally following the criteria that emerged from this analysis.[3] The following contemporaries of Mozart signed loose portraits of him:[3][5] Pompeo Batoni, François Joseph Bosio, Breitkopf, Joseph Duplessis, Nicolò Grassi, Jean-Baptiste Greuze, Giambettino Cignaroli, Louis Carrogis Carmontelle, Johann Nepomuk della Croce, Dominicus van der Smissen, Martin Knoller, Dora Stock, and Pietro Antonio Lorenzoni, among many others. Although they are not faithful to the physical features of the composer, these portraits provide important iconographic data either on musical instruments or on other people appearing in them.[3] The inauthentic portraits consist of three types. First are portraits of other people (most often young male musicians), claimed later to be of Mozart. Second are forgeries of various kinds, created for money or fame, in which the image is claimed to represent Mozart but is fabricated. The third category is formed by fantastical paintings, the product of the artist's imagination, with no basis in Mozart's actual appearance or in existing iconography. Most of these are inspired by the abundant supply of myths and legends that arose surrounding Mozart.[7][8] Authentic portraits of MozartEven the few portraits that have passed muster as authentic have not escaped criticism. Alfred Einstein wrote: "No earthly remains of Mozart survived save a few wretched portraits, no two of which are alike".[9] Anonymous 1763 portraitThis shows Mozart in front of a keyboard looking at the viewer, dressed in court costumes given to him in 1762 as a gift from Empress Maria Theresa, which came from the wardrobe of Archduke Maximilian Francis of Austria,[10] as documented in a letter by Wolfgang's father Leopold Mozart on 19 October 1762.[11] It is considered to be the earliest authentic portrait of Mozart, being commissioned by Leopold himself. It is attributed to Austrian painter Pietro Antonio Lorenzoni,[12] who also painted Wolfgang's sister Maria Anna Mozart. The artist executed first the interiors, instruments and clothes before the children posed.[13] It is oil on canvas, and currently owned by the Mozarteum in Salzburg (inherited directly from the Mozart family)[10] and displayed at Mozart's birthplace. Multiple copies of the painting also exist in different media. Carmontelle's 1763–64 family portraitThis shows Wolfgang at the harpsichord, with Leopold behind playing the violin and Maria Anna "as if she were singing". It was painted by French artist Louis Carrogis Carmontelle during the stay of the Mozart family in Paris of 1763-64,[14] part of the grand family tour through most of Western Europe. It was commissioned by Friedrich Melchior, Baron von Grimm, patron of the Mozarts at the time.[15] The subsequent engraving copy made from it is documented in a letter from Leopold to Lorenz Hagenauer on 1 April 1764.[16] A large number of copies of the engraving were made, which Leopold used for advertising and gift purposes, and some of which he also sold.[17] Mozart's sister was referring to the engraving when she wrote to Breitkopf & Sohn on 24 November 1799:[18]

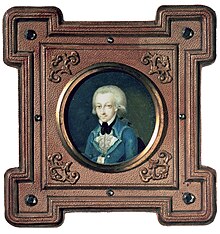

It is a watercolour on paper, with subsequent copies being made on griffel, sanguine, gouache, and engraving. The original is currently owned by and exhibited at the Musée Condé in the Château de Chantilly.[21] Anonymous 1770 Verona portrait This shows Mozart looking at the viewer while playing the dubious "Molto allegro" in G major (K. 72a),[22] on a harpsichord made in Venice on 1583 by Giovanni Celestius.[23] It was painted in Verona between January 6–7 of 1770,[24] commissioned by Venetian tax collector Pietro Lugiati, who also housed Mozart and his father during their stay in the city.[23] Leopold Mozart reports on the origins of this picture in his letter to his wife on 7 January 1770.[25][26] The authorship is disputed between Saverio Dalla Rosa and Giambettino Cignaroli.[27] Arthur Schurig considered it to be the best and most faithful portrait of Mozart as a young man.[25] It is oil on canvas, and was previously owned by the descendants of pianist Alfred Cortot,[28] but it was sold to an anonymous art collector in 2019 at a Christie's auction house in Paris. Initally valued at around one million euros, the painting was finally acquired for over four million,[29] making it not only the highest-priced portrait of Mozart, but the highest-priced artefact related to him. Anonymous 1773 miniature This shows the upper half of Mozart looking at the viewer. It was apparently painted in Milan in 1773, during the third journey of Mozart in Italy. It is attributed to the Austrian-Italian artist Martin Knoller, a teacher in the academy of arts of Milan at the time.[30] Knoller was known to the Mozart family even before the first trip to Italy, according to a letter by Leopold to his wife on 17 February 1770.[31][32] The portrait was in the possession of Wolfgang's sister Maria Anna Mozart, possibly given by Mozart himself. The dating of this picture derives from a letter of 2 July 1819, in which she referred to the painting.[33][34][31] Barbara Krafft probably took it, alongside the Salzburg family portrait and Lange's miniature as a basis for her own posthumous portrait. Despite this, a few experts still cast doubts on its authenticity.[35] It is a watercolour on ivory, surrounded by a leather frame, and currently owned by the Mozarteum in Salzburg.[36] Anonymous 1777 Bologna portraitThis represents Mozart wearing the chivalric Order of the Golden Spur, conferred on him by Pope Clement XIV on 4 July 1770.[37] It is an anonymous copy realised in Salzburg in 1777, from a lost original dated 1770,[38] commissioned by Giovanni Battista Martini. Wolfgang met Martini in Bologna in 1770, during his first travel to Italy. The friar instructed the young Mozart and helped him in being accepted as a member of the famous Accademia Filarmonica di Bologna,[39][40] one of the most respected musical institutions in Europe at the time. The painting is mentioned by Leopold in a letter to Martini, who remarked "It has little value as a piece of art, but as to the issue of resemblance, I can assure you that it is perfect".[41][42] It is attributed to Johann Nepomuk della Croce.[43] It is oil on canvas, and is currently exhibited at the Museo internazionale e biblioteca della musica in Bologna.[44] A copy was made in 1925 by Italian painter Antonio Maria Nardi, which is owned and exhibited by the Mozarteum in Salzburg.[45] Another copy in watercolour was realised by John Singer Sargent in 1873, exhibited at the Fitzwilliam Museum.[46] Anonymous 1780–81 family portraitThis shows Wolfgang and his sister Maria Anna playing four hands on a keyboard, with Leopold by the side holding a violin. In the wall hangs a medallion with the picture of Anna Maria Mozart, who had died suddenly in 1778 while accompanying Wolfgang in travel to Paris.[47] The small statue of Apollo in the background symbolizes the musical nature of the Mozart family.[48] The portrait was painted between 1780 and 1781, traditionally attributed to Johann Nepomuk della Croce, but this is disputed by scholars such as Simon Keefe, who claims it was created in an anonymous Salzburg workshop,[49] and George Dieter, who points to a name confusion as the origin of the supposed attribution.[50] The painting was commissioned by Leopold,[48] and its progress is referenced in a series of letters between Wolfgang, Maria Anna and Leopold.[51][52][53][54][55][56] After Mozart's death, Barbara Krafft used his portrayal as a basis for her own posthumous portrait.[38]: Notes on Table 1 In 1829, when Mary and Vincent Novello met with and interviewed Constanze Mozart, her son Franz Xaver Wolfgang Mozart stated that the image of Wolfgang in this painting was one of the best likenesses of him.[57] It is oil on canvas, currently owned and exhibited at the Mozarteum in Salzburg.[58] Lange's 1782–83 unfinished portraitThis shows Mozart (without wig) from the shoulders upwards. It was painted between 1782 and 1783[59] by Austrian actor and amateur painter Joseph Lange, brother-in-law of Mozart. It was originally a completed miniature before being affixed to a larger canvas, probably with the intention of portraying the composer playing the keyboard, but the enlarged painting was never completed,[60][61] fostering false theories that it was begun shortly before Mozart's death in 1791. This miniature origin was rediscovered in 2009 by musicologist Michael Lorenz, after a very intensive restoration in the early 1960s had blurred the limits.[61] In spring of 1783, Mozart had the miniature sent to his father in Salzburg, alongside with a similar one of Constanze, both referenced in a letter.[62][63] Lange had a personal relationship with Mozart beyond common family ties: both were masons and socialized around the same circles.[64] Lange had a couple of roles in Mozart's works, most notably the Musik zu einer Pantomime (K. 446/416d)[59] and the comic singspiel Der Schauspieldirektor (K. 486).[65] Lange also painted a small portrait of Constanze in 1782 which was later also enlarged.[61] During Leopold Mozart's visit to Vienna in 1785, Lange drew a portrait of him as well, but this depiction was lost.[66] After Mozart's death, when Constanze was interviewed by Vincent and Mary Novello, she said that Lange's portrait was "by far the best likeness of him".[67][68][69][70][71] On the other hand, Schurig described it as "of little artistic value, but despite the intention to beautify it, it is not without charm".[62] It is oil on canvas, currently owned and exhibited at the Mozarteum in Salzburg.[72] Anonymous 1783–85 portrait A side profile of the upper half of Mozart. It is dated circa 1783–85 and attributed to Austrian artist Joseph Hickel, part of the Austrian Imperial Court.[73] The painting was in possession of the Hagenauer family, which had strong ties with the Mozarts.[74] It was bought in 2005 by an American collector and rediscovered in a 2008 auction in London, which began an authentication process.[75] It is considered authentic by the Mozarteum in Salzburg, supported by experts Cliff Eisen,[76] Simon Keefe[77] and Martin Braun[78] among others. Eisen pointed out that the red coat of the painting matched the description of a coat Mozart desired and obtained, as documented in two letters of the period.[79][80] Braun realised an extensive study of the painting, comparing with the authentic ones and analysing the facial features, concluding it was authentic.[81] It is oil on canvas, currently owned by a private collector. Stock's 1789 miniature This portrait, another side profile, was realised during Mozart's stay in Dresden in April 1789, while he was on a journey to Berlin. Mozart visited the family of consistorial councillor Christian Gottfried Körner, a friend of Schiller. A member of the family was Körner's sister-in-law Dora Stock, who was a talented artist and took the occasion to sketch a portrait of Mozart.[82][83][84] It is considered the last authentic portrait of Mozart before his death in 1791. (Some doubts are cast by Cliff Eisen[85] and other experts,[86] most notably because of the lack of mentions in the Mozart correspondence, but it is still widely considered to be authentic.) The work is in silverpoint on ivory board and is currently owned by the Mozarteum in Salzburg. Due to its fragility and the potential harm of the sun, the original is protected in the museum vault, only a copy being exhibited. Krafft's posthumous 1819 portrait This is by far the most commonly reproduced and most famous portrait of Mozart, enjoying enormous popularity since the bicentenary of 1956.[87] It was created in 1819 (28 years after Mozart's death) by Austrian painter Barbara Krafft,[88] commissioned by Joseph Sonnleithner for a portrait collection of well-known composers in the Society of Friends of Music in Vienna.[89] For the task, Krafft was supplied with three portraits of Mozart given by Maria Anna Mozart;[90][91][92] (1) Possibly the 1773 miniature (2) The 1780 Salzburg family portrait and (3) The miniature version of the Lange portrait.[93] Thus, despite being painted posthumously, the portrait is considered as very accurate to Mozart's real appearance, as corroborated by her sister Maria Anna.[94][95][6] It is oil on canvas, currently part of the collection of Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde. Dubious portraits of MozartGreuze's 1763–64 portrait This supposedly shows the upper half of Mozart as painted by French artist Jean-Baptiste Greuze. Like Carmontelle's watercolour, it was apparently created during the stay of the Mozart family in Paris in 1763–64.[96] Before the sitter was thought to be Mozart, the picture was known as "portrait of a boy", and it was speculated that Greuze was the painter. The rediscovered portrait was first exhibited at the Mozart Museum in Salzburg, during the Mozart Festival of 1910 from July 25 to October 28.[97] The authorship of Greuze was confirmed after his signature was found in the portrait. However, the identification of the sitter as Mozart has never been fully confirmed, and therefore should be treated with scepticism. We find no mention of the painting in the correspondence of the Mozart family, nor do the biographers of Mozart or Greuze mention it. Leisching and Schurig described the portrait as either inauthentic or a forgery,[98][99] but this was before the signature and other details were discovered. Deutsch also considered it to be inauthentic.[6] Composer and neurobiologist Martin Braun realised an extensive study of the portrait, analysing the facial features and comparing them with the known authentic portraits of Mozart. He came to the conclusion that not only was the painting authentic, but the model was effectively Mozart himself.[96] This claim is supported by Mozart lecturer Daniel N. Leeson. It is oil on canvas, and is currently owned by Yale University and exhibited at Yale University Art Gallery.[100] Anonymous 1763–67 dual miniature portrait This supposedly represents Wolfgang and his sister Maria Anna, who holds a music score. It was created circa 1763–67, and attributed to Austrian court miniaturist Johann Eusebius Alphen (1741–1772). Alphen met the Mozart family on several occasions in those years in Brussels, Paris and Vienna.[101][102][103] Arthur Schurig included the miniature in his list of inauthentic Mozart portraits, but without bringing any concrete evidence as of why.[104] On the other hand, Canadian musicologist and Mozart expert Cliff Eisen concluded that the miniature was authentic.[105] However, it is still considered doubtful by most experts. It is watercolour and opaque or poster paint on ivory, and currently owned by the Mozarteum in Salzburg. Anonymous 1767–68 portrait This supposedly shows Mozart holding a score while looking at the viewer. It was apparently painted circa 1767–68 in Vienna,[106] authorship being disputed between Johann Eusebius Alphen and Pietro Antonio Lorenzoni. According to Mozart expert Manfred Schmid, the painting was in possession of the Hagenauer family (whose members were very close to the Mozart family and frequently appear in their correspondence),[107] Their Mozart collection was sold circa 1920 in Cologne. However, lack of provenance for the painting has kept experts and researchers divided as to its authentication. Mozart musicologist Rudolph Angermüller expressed positive views on it. The technique used is unknown. It is currently owned and displayed at the Mozarteum in Salzburg.[106] Anonymous 1770 Florence portrait This apparently shows Mozart at the keyboard, surrounded by the Gavard des Pivets family and Thomas Linley playing the violin. It was supposedly painted in 1770 in Florence, where Leopold and Wolfgang encountered violinist Pietro Nardini, whom they had met at the start of their grand tour of Europe.[108] However, no firm authorship of any artist has yet been established. Giuseppe Maria Gavard des Pivets was the finance administrator of the court of Grand Duke of Tuscany Leopoldo I (later Holy Roman Emperor Leopold II).[109] Wolfgang also met Thomas Linley, an English violin prodigy and a pupil of Nardini. The two formed a close friendship, making music and playing together "not as boys but as men", as Leopold remarked.[110][111] However, we find no mention of a painting being made for the occasion, and neither is there any reference to a pictorial representation in the correspondence of the Mozart family, and thus the portrait is considered dubious. It is oil on canvas, was previously owned by the descendants of pianist Alfred Cortot, and has been owned by a private collector since it was sold in an auction in 2019.[112] Delahaye's 1772 portrait This apparently shows the upper half of Mozart. It is dated 1772 and executed by French painter Jean-Baptiste Delahaye[113] on the reverse of the canvas.[114] However, it is heavily disputed whether the portrayed is actually Mozart. Martin Braun analyzed and compared the painting with authentic portraits (Bologna and Salzburg family paintings), and concluded that the facial elements of the sitter matched Mozart's.[114] Despite this, it is still considered inauthentic by several Mozart experts.[38] No references to the portrait appear in the Mozart correspondence, nor do external facts confirm the attribution. The painting was previously known as "Portrait of a Young Man", bringing the possibility that the sitter was claimed to be Mozart long after the artwork was made. It is oil on canvas; its earliest known owner was the writer Duchess Mechtilde Christiane Maria Lichnowsky, née Countess von und zu Arco-Zinneberg.[115] She was a descendant of the Arco and Lichnowsky families, which had close ties to the Mozarts, and possibly acquired the portrait.[116] It is currently privately owned after a January 2006 auction in Salzburg. Anonymous 1773–75 portrait This apparently shows Mozart looking at the viewer while wearing a valuable diamond ring, which he received as a gift from Empress Maria Theresa on 3 October 1762.[30] It is dated circa 1773–75, and no firm authorship of any artist has yet been established. Schurig initially considered it to be inauthentic,[117] but later changed his mind, remarking on the similarity of the facial features when compared with the authentic paintings.[30] Despite this, it is still considered doubtful due to a lack of research and consensus among experts. It is oil on canvas, currently owned and exhibited at the Mozarteum in Salzburg.[118] Anonymous 1780–83 miniature This supposedly shows Mozart.[119] It is dated circa 1780–83 and attributed to Johann Nepomuk della Croce. It's considered dubious and is not mentioned in the correspondence of the family. Schurig included it in his list of inauthentic portraits, pointing at physical differences in the ears when compared with the authentic paintings.[119] It is gouache on parchment, and currently owned by the Vienna Museum.[120] Grassi's 1783–85 portrait This apparently represents Mozart circa 1783–85. It is attributed to Austrian painter Josef Grassi, supposedly having been lost and rediscovered in Moscow in 1988. As with most of the dubious portraits, we find no reference or mention in the family correspondence, or other direct source from the period. The painting also has not yet been analyzed by Mozart experts or studied to determine its authenticity. It is known that Mozart and Grassi met in Vienna after the former's arrival there.[121] It is oil on canvas or cardboard, and currently part of the collection of the Glinka Music Museum in Moscow.[122][123] Edlinger 1790 portrait This is by far the most controversial and divisive of the doubtful Mozart portraits. It was supposedly painted in Munich between October and November of 1790 by Austrian artist Johann Georg Edlinger, during Mozart's stay in that city just a year before his death. In a letter to Constanze, the composer wrote that he originally wanted to stay for a single day, but the Elector asked him to remain to perform a concert for kings of the Two Sicilies Ferdinand I and Maria Carolina of Austria. Mozart also took advantage and visited several friends he had met in Mannheim.[124][125] The portrait was bought from a Munich art dealer in 1934, and remained in a gallery warehouse for 70 years.[126] It remained there, both the sitter and the author being unknown until 1981, when Rolf Schenk identified the painting as a work of Edlinger.[127] In 1995, Wolfgang Seiller, a descendant of Edlinger, noticed a similarity of the person depicted to Mozart in the Bologna portrait. Four years later, Rainer Michaelis and Wolfgang Seiller confirmed this attribution based on biographical data of Mozart and Edlinger, as well as on a detailed comparison of the portraits.[128] This claim was also supported by Schenk. After a restoration in 2004, the portrait was exhibited to the public on January 27 of 2005, on Mozart's 249th anniversary,[129] and news of the discovery quickly spread.[130][131][129] Most of these focused on the unflattering physical portrayal of Mozart. Several Mozart scholars, historians and musicologist examined the portrait and a division formed between supporters and deniers of the authenticity of the painting. Rudolph Angermüller and Gabriele Ramsauer questioned that the sitter was Mozart, asserting that it was instead a local businessman named Joseph Anton Steiner.[132][133] This issue was addressed by Braun and Michaelis, both of whom pointed out that two different portraits had been mixed up.[134] Braun also realised a detailed comparison with the Bologna portrait, further solidifying his claim that the sitter was Mozart.[128] On the other hand, scholar Volkmar Braunbehrens argued that, while Mozart did visit the city in that year, there is no reference of a painting being realised during the stay. Not only that, but the painter's name is also absent in Mozart's letters of these days.[135] John Jenkins is also cautious on the Mozart attribution, pointing to multiple differences with Lange's portrait as an example.[135] Volker Hagedorn was also critical of the attribution and its inconsistencies.[136] In 2006, the Mozart attribution was also confirmed by four art historians at the Austrian State Gallery in Vienna: Gerbert Frodl, Sabine Grabner, Michael Krapf, and Udo Felbinger. Sculptor Wolfgang Eckert realised a bust based on the painting, and during the project he concluded that the 1789 miniature made by Dora Stock shows the greatest similarity to Edlinger's portrait, which also would substantiate the attribution of a Mozart image created by Edlinger.[137] It is oil on canvas, and is owned and exhibited by the Gemäldegalerie Museum.[138] Inauthentic portraits of MozartHelbling's 1765–67 portrait This supposedly shows Mozart looking at the viewer while playing the keyboard. It is dated circa 1765–67, painted by Austrian artist Franz Thaddäus Helbling.[139] For a long time it was considered to be authentic, being included in Schurig's list of authentic portraits of Mozart.[140] However, on further inspection, it was discovered that the sitter is actually Count Karl Maximilian Graf Firmian.[38][141] It is oil on canvas, and currently owned by the Mozarteum in Salzburg.[142] Smissen's 1766 portrait This apparently shows a young Mozart. It was allegedly painted in Holland in the spring of 1766 by German artist Dominicus van der Smissen. On the back is a handwritten note: "Mozart as a youth, painted by van Smissen." This is impossible because Smissen died on 6 January 1760.[104] It also has been attributed to a non-existent J. Vander Smissen, or even Domenicus' son Jakob van Smissen (1735–1813). A false idea of explaining the signature as "Devotus van Smissen" was born, because Smissen was supposed to have been a devout Mennonite.[104] The portrait itself lacks any fidelity to the model, specially in the face features and eye colour. The painting is probably a forgery created to capitalize on the name of the composer. It is oil on canvas, and currently in the Mozarteum in Salzburg. Anonymous 1767 portrait This supposedly shows Mozart at the keyboard, wearing a Chinese coat and looking at the viewer while pages of a score lie in his lap. It was apparently painted in 1767, and attributed to either Jean-Baptiste Perronneau or Joseph Duplessis. However, no evidence connects the boy in the picture with Mozart.[143] We find no reference to the painting in the correspondence of the Mozart family, nor does any clue indicate the composer is the model, suggesting that the sitter was falsely attributed to be Mozart much later on. It is oil on canvas, and currently owned by the Louvre Museum and exhibited at Musée de la Musique.[144] Dubeck or Jäger's 1808/1870 portrait This, supposedly representing Mozart, was painted by Burchard Dubeck in 1808, 17 years after the death of Mozart. It is also attributed to German painter Karl Jäger and dated 1870. Not much is known about the painting and the circumstances surrounding it, as no detailed investigation has yet been done. It is widely considered to be inauthentic for the lack of fidelity to the model, specially when compared with the authentic portraits. Max Zenger included it in his list of false portraits, favoring the 1870 date, and attacking it with relish: the work is a "paradigm example of kitsch portrayals"; and noting that even at the time of writing (1941) it is "by no means to be found solely on candy boxes."[98] The work is now privately owned; the medium used is unknown.[145] Kaulbach's 1873 painting Better known as "Mozart's Last Days", this shows the dying composer attended by his wife Constanze and his sister-in-law Sophie Weber, with the unfinished Requiem at his feet while his friends in the background rehearse the work. It was painted in 1873 by German artist Hermann von Kaulbach, and acquired by the Vienna Gallery (currently the Vienna Museum) in 1874.[146] The painting was very popular, specially after an engraving of it was realized. However, the picture forms part of the fantasy portrayals of Mozart, offering a purely romantic vision of the physical appearance of the composer, disregarding the authentic extant iconography. It is oil on canvas, and the original is currently exhibited at the Mozarteum in Salzburg. The painting is based on a story told about Mozart in the 19th century; i.e. that he really did participate in a rehearsal of his Requiem on the day before his death. In the preserved version of the story, there were only four singers present, of which one was Mozart himself. For details and origin see Benedikt Schack and Death of Mozart. See alsoReferences

Sources

|