|

Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind (manga)

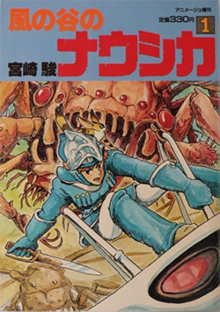

Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind (Japanese: 風の谷のナウシカ, Hepburn: Kaze no Tani no Naushika) is a Japanese manga series written and illustrated by Hayao Miyazaki. It tells the story of Nausicaä, a princess of a small kingdom on a post-apocalyptic Earth with a toxic ecosystem, who becomes involved in a war between kingdoms while an environmental disaster threatens humankind. Prior to creating Nausicaä, Miyazaki had worked as an animator for Toei Animation, Nippon Animation and Tokyo Movie Shinsha (TMS), the latter for whom he had directed his feature directorial debut, Lupin III: The Castle of Cagliostro (1979). After working on an aborted film adaptation of Richard Corben's comic book Rowlf for TMS, he agreed to create a manga series for Tokuma Shoten's monthly magazine Animage, initially on the condition that it would not be adapted into a film. The development of Nausicaä was influenced by the Japanese Heian period tale The Lady who Loved Insects, a similarly-named character from Homer's epic poem Odyssey and the Minamata Bay mercury pollution. The setting and visual style of the manga was influenced by Mœbius. It was serialized intermittently in Animage from February 1982 to March 1994 and the individual chapters were collected and published by Tokuma Shoten in seven tankōbon volumes. It was serialized with an English translation in North America by Viz Media from 1988 to 1996 as a series of 27 comic book issues and has been published in collected form multiple times. Since its initial serialization, Nausicaä has become a commercial success, particularly in Japan, where the series has more than 17 million copies in circulation. The manga and the 1984 film adaptation, written and directed by Miyazaki and released following the serialization of the manga's first sixteen chapters, received universal acclaim from critics and scholars for its characters, themes, and art. The manga and film versions of Nausicaä are also credited for the foundation of Studio Ghibli, the animation studio for which Miyazaki created several of his most recognized works. SynopsisSettingThe story is set in the future at the closing of the ceramic era, 1,000 years after the Seven Days of Fire, a cataclysmic global war, in which industrial civilization self-destructed. Although humanity survived, the land surface of the Earth is still heavily polluted and the seas have become poisonous. Most of the world is covered by the Sea of Corruption, a toxic forest of fungal life and plants which is steadily encroaching on the remaining open land. It is protected by large mutant insects, including the massive Ohmu. Humanity clings to survival in the polluted lands beyond the forest, periodically engaging in bouts of internecine fighting for the scarce resources that remain. The ability for space travel has been lost but the earth-bound remnants of humanity can still use gliders and powered aircraft for exploration, transportation and warfare. Powered land vehicles are entirely nonexistent though, with humanity regressed to dependence on riding animals and beasts-of-burden. Plot Nausicaä is the teenage princess of the Valley of the Wind, a state on the periphery of what was once known as Eftal, a kingdom destroyed by the Sea of Corruption, a poisonous forest, 300 years ago. An inquisitive young woman, she explores the territories surrounding the Valley on a jet-powered glider, and studies the Sea of Corruption. When the Valley goes to war, she takes her ailing father's place as military chief. The leaders of the Periphery states are vassals to the Torumekian Emperor and are obliged to send their forces to help when he invades the neighboring Dorok lands. The Torumekians have a strong military, but the Doroks, whose ancestors bioengineered the progenitors of the Sea of Corruption, have developed a genetically modified version of a mold from the Sea of Corruption. When the Doroks introduce this mold into battle, its rapid growth and mutation result in a daikaisho (roughly translated from Japanese as "great tidal wave"), which floods across the land and draws the insects into the battle, killing as many Doroks as Torumekians. In doing so, the Sea of Corruption spreads across most of the Dorok nation, uprooting or killing vast numbers of civilians and rendering most of the land uninhabitable. The Ohmu and other forest insects respond to this development and sacrifice themselves to pacify the expansion of the mold, which is beyond human control. Nausicaä resigns herself to joining in their fate. However, one of the Ohmu encapsulates her inside itself in a protective serum, allowing her to survive the mold. She is recovered by her companions, people she met after leaving the Valley and who have joined her on her quest for a peaceful coexistence. The fact that the mold can be manipulated and used as a weapon disturbs Nausicaä. Her treks into the forest have already taught her that the Sea of Corruption is actually purifying the polluted land. The Forest People, humans who have learned to live in harmony with the Sea of Corruption, confirm this is the purpose of the Sea of Corruption and one of them shows Nausicaä a vision of the restored Earth at the center of the forest. Nausicaä travels deeper into Dorok territory, where her coming has long been prophesied, to seek those responsible for manipulating the mold. There, she encounters a dormant God Warrior who, upon activation, assumes she is his mother and places his destructive powers at her disposal. Faced with this power and its single minded and childlike visions of the world, she engages the creature, names him and persuades him to travel with her to Shuwa, the Holy City of the Doroks. Here she enters the Crypt, a giant monolithic construct from before the Seven Days of Fire. She learns that the last scientists of the industrial era had foreseen the end of their civilization. They created the Sea of Corruption to clean the land of pollution, altered human genes to cope with the changed ecology, stored their own personalities inside the Crypt and waited for the day when they could re-emerge, leaving the world at the mercy of their artificially created caretaker. However, their continual manipulation of the population and the world's environment is at odds with Nausicaä's belief in the natural order. She argues that mankind's behaviour has not been improved significantly by the activities of those inside the crypt, and the crypt itself is incapable of change. Strife and cycles of violence have continued to plague the world in the thousand years following their interference, as Nausicaä believes humanity has no need for the crypt any longer. She orders the God-Warrior to destroy its progenitors, forcing humanity to live or die without further influence from the old society's technology. Nausicaä exits the crypt in time to see its total collapse, and the death of the old king of Torumekia. Nausicaä commands the crowd that has been waiting outside the crypt that "... they must live." DevelopmentPrecursors and early developmentMiyazaki began his professional career in the animation industry as an inbetweener at Toei in 1963 but soon had additional responsibilities in the creation processes.[2] While working primarily on animation projects for television and cinema, he also pursued his dream of creating manga.[3] In conjunction with his work as a key animator on the film The Wonderful World of Puss 'n Boots (1969) his manga adaptation of the same title was published in 1969. That same year a pseudonymous serialization started of his manga People of the Desert. His manga adaptation of the film Animal Treasure Island (1971) was serialized in 1971.[4] After the release of Lupin III: The Castle of Cagliostro (1979), Miyazaki, now at the Tokyo Movie Shinsha (TMS), began working on his ideas for an animated film adaptation of Richard Corben's comic book Rowlf and pitched the idea to Yutaka Fujioka at TMS. In November 1980, a proposal was drawn up to acquire the film rights.[5] Around that time Miyazaki was also approached for a series of magazine articles by the editorial staff of Tokuma Shoten's Animage. During subsequent conversations he showed his sketchbooks and talked about basic outlines for envisioned animation projects with Toshio Suzuki and Osamu Kameyama, at the time working as editors for Animage. They saw the potential for collaboration on Tokuma's development into animation. Initially two projects were proposed to Tokuma Shoten, that are significant for the eventual creation of Nausicaä: Warring States Demon Castle (戦国魔城, Sengoku ma-jō), to be set in the Sengoku period, and the adaptation of Corben's Rowlf, but they were rejected, on July 9, 1981. The proposals were rejected because the company was unwilling to fund anime projects not based on existing manga and because the rights for the adaptation of Rowlf could not be secured.[6] An agreement was reached that Miyazaki could start developing his sketches and ideas into a manga for the magazine with the proviso that it would never be made into a film.[7][a] Miyazaki stated in an interview, "Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind only really began to take shape once I agreed to serialize it."[9] In the December 1981 issue of Animage, it was announced that a new manga series would start in the February 1982 issue of the magazine, despite the fact that Miyazaki had not completed the first episode. The illustrated notice introduced the new series' main character, title and concept.[10] The first chapter, 18 pages, was published in the February 1982 issue. Miyazaki would continue developing the story for another 12 years with frequent interruptions along the way.[11] Influences Miyazaki had given other names to the main character during development, but he settled on Nausicaä based on the name of the Greek princess of the same name from the Odyssey, as portrayed in Bernard Evslin's Encyclopedia of Greek mythology, translated into Japanese by Minoru Kobayashi.[b] In his essay On Nausicaä (ナウシカのこと, Naushika no koto), printed in volume one of the manga, Miyazaki wrote that he was also inspired by The Lady who Loved Insects, a Japanese tale from the Heian period about a young court lady who preferred studying insects rather than wearing fine clothes or choosing a husband.[15] Helen McCarthy considers Shuna from Shuna's Journey to be prototypical to Nausicaä.[16] The story’s fantasy and science fiction elements were influenced by a variety of works from Western authors, including Ursula K. Le Guin's Earthsea, Brian Aldiss's Hothouse, Isaac Asimov's Nightfall, and J.R.R Tolkien's The Lord of the Rings.[17] The setting and visual style of the manga often reference Jean Giraud (Mœbius), whose wordless 1975 comic Arzach had deeply impressed Miyazaki.[18] Among the inspirations for the environmental themes Miyazaki has mentioned the Minamata Bay mercury pollution.[citation needed] The Sea of Corruption is based on the forests on the Japanese island of Yakushima and the marshes of the Sivash, or Rotten Sea, in Ukraine.[19][c] The works of botanist Sasuke Nakao were among Miyazaki's inspirations for the environment of the story. Miyazaki mentions Nakao in the context of a question he was asked about the place Nausicaä takes in the ecology boom, explaining his shift from a desert to a forest setting. Nakao's influence on his work has been noted by Shiro Yoshioka.[21] Miyazaki has identified Tetsuji Fukushima's Sabaku no Maō 沙漠の魔王 (The Evil Lord of the Desert), a story he first read while still in primary school, as one of his earliest influences. Kentaro Takekuma has also observed this continuity in Miyazaki's work and places it within the tradition of illustrated stories, emonogatari (絵物語), and manga Miyazaki read while growing up, pointing out the influence of Fukushima on Miyazaki's People of the Desert which he in turn identifies as a precursor for both Shuna's Journey, created in watercolour and printed in colour, and Nausicaä.[22] CreationMiyazaki drew the Nausicaä chapters primarily in pencil. The work was printed monochrome in sepia toned ink.[23][d] Frederik L. Schodt observed differences between Nausicaä and other Japanese manga. He has noted that it was serialized in the large A4 size of Animage, much larger than the normal size for manga. Schodt has also observed that Miyazaki drew much of Nausicaä in pencil without inking, and that the page and panel layouts, as well as the heavy reliance on storytelling, are more reminiscent of French comics than of Japanese manga. In appearance and sensibilities, Nausicaä reminds Schodt of the works of Mœbius.[24] Takekuma has noted stylistic changes in Miyazaki's artwork over the course of the series. He points out that, particularly in the first chapters, the panels are densely filled with background, which makes the main characters difficult to discern without paying close attention. According to Takekuma this may be partially explained by Miyazaki's use of pencil, without inking, for much of the series. Takekuma points out that by employing pencil Miyazaki does not give himself the option of much variation in his line. He notes that in the later chapters Miyazaki uses his line art to draw attention to individuals and that he more frequently separates them from the background. As a result there are more panels in which the main characters stand out vividly in the latter part of the manga.[25] Miyazaki has stated in interviews that he frequently worked close to publication deadlines and that he was not always able to finish his monthly instalments for serialization in Animage. On such occasions he sometimes created apologetic cartoons. These were printed in the magazine, instead of story panels, to explain to his readers why there were fewer pages that month or why the story was absent entirely. Miyazaki has indicated that he continued making improvements to the story prior to the publication of the tankōbon volumes, in which chapters from the magazine were collected in book form.[26] Changes made throughout the story, before the release of each tankōbon volume, range from subtle additions of shading to the insertion of entirely new pages. Miyazaki also redrew panels and sometimes the artwork was changed on whole pages. He made alterations to the text and changed the order in which panels appeared. The story as re-printed in the tankōbon spans 7 volumes for a combined total of 1060 pages.[27] Miyazaki has said that the lengthy creation process of the Nausicaä manga, repeatedly tackling its themes as the story evolved over the years, not only changed the material but also affected his personal views on life and changed his political perspectives. He also noted that his continued struggle with the subject matter in the ongoing development of the Nausicaä manga allowed him to create different, lighter, films than he would have been able to make without Nausicaä providing an outlet for his more serious thoughts throughout the period of its creation.[28] Marc Hairston notes that, “Tellingly, Miyazaki’s first film after finishing the Nausicaä manga was Mononoke Hime, which examined many of the themes from the manga and is arguably the darkest film of his career.”[29] LocalizationNausicaä of the Valley of the Wind was initially translated into English by Toren Smith and Dana Lewis. Smith, who had written comics in the U.S. since 1982, wrote an article on Warriors of the Wind (the heavily edited version of the film adaptation released in the U.S. in the 1980s) for the Japanese edition of Starlog, in which he criticized what Manson International had done to Miyazaki's film. The article came to the attention of Miyazaki himself, who invited Smith to Studio Ghibli for a meeting. On Miyazaki's insistence, Smith's own company Studio Proteus was chosen as the producer of the English-language translation. Smith hired Dana Lewis to collaborate on the translation. Lewis was a professional translator in Japan who also wrote for Newsweek and had written cover stories for such science fiction magazines as Analog Science Fiction and Fact and Amazing Stories. Smith hired Tom Orzechowski for the lettering and retouching.[30] Studio Proteus was responsible for the translation, the lettering, and the retouching of the artwork, which was flipped left-to-right to accommodate English readers. The original Japanese dialogue was re-lettered by hand, the original sound effects were replaced by English sound effects, and the artwork was retouched to accommodate the new sound effects. When Miyazaki resumed work on the manga following one of the interruptions, Viz chose another team, including Rachel Thorn and Wayne Truman, to complete the series.[31] The current seven-volume, English-language "Editor's Choice" edition is published in right-to-left reading order: while it retains the original translations, the lettering was done by Walden Wong. The touch-up art and lettering for the Viz Media deluxe two-volume box set was also done by Walden Wong.[32][33] Eriko Ogihara-Schuck compared the Japanese-language manga and anime with their English translations, and demonstrated that American translations resulted in the "Christianizing of Miyazaki's animism", especially in the film version. One cause is the lack of English equivalents for some Japanese concepts; the other is the Judeo-Christian background and idioms of the Western translators, which introduced a dualistic worldview absent in the original.[34] Publication history The manga was serialized in Tokuma Shoten's monthly Animage magazine between 1982 and 1994.[35] The series initially ran from the February 1982 issue to the November 1982 issue when the first interruption occurred due to Miyazaki's work related trip to Europe.[36] Serialization resumed in the December issue and the series ran again until June 1983 when it went on hiatus again due to Miyazaki's work on the film adaptation of the series. Serialization of the manga resumed for the third time from the August 1984 issue but halted again in the May 1985 issue when Miyazaki placed the series on hiatus to work on Castle in the Sky. Serialization resumed for the fourth time in the December 1986 issue and was halted again in June 1987 when Miyazaki placed the series on hiatus to work on the films My Neighbor Totoro and Kiki's Delivery Service. The series resumed for the fifth time in the April 1990 issue and was halted in the May 1991 issue when Miyazaki worked on Porco Rosso. The series resumed for the final time in the March 1993 issue. The final panel is dated January 28, 1994. The last chapter was released in the March 1994 issue of Animage. By the end Miyazaki had created 59 chapters, of varying length, for publication in the magazine. In an interview, conducted shortly after serialization of the manga had ended, he noted that this amounts to approximately 5 years worth of material. He stated that he did not plan for the manga to run that long and that he wrote the story based on the idea that it could be stopped at any moment.[37][38] The chapters were slightly modified and collected in seven tankōbon volumes, in soft cover B5 size.[39] The first edition of volume one is dated September 25, 1982. It contains the first eight chapters and was re-released on July 20, 1983, with a newly designed cover and the addition of a dustcover.[40][e] Volume two has the same July 20, 1983, release date. It contains chapters 9 through 14. Together with chapters 15 and 16, printed in the Animage issues for May and June 1983, these were the only 16 chapters completed prior to the release of the Nausicaä film in March 1984. The seventh book was eventually released on January 15, 1995.[40] The entire series was also reprinted in two deluxe volumes in hard cover and in A4 size labeled Jokan (上巻, first volume) and Gekan (下巻, final volume) which were released on November 28, 1996.[42][43] The seven books, which remain in print individually, have also been released in box sets twice, on August 25, 2002, and, with a redesigned box, on October 31, 2003.[44][45] English translations are published in North America and the United Kingdom by Viz Media. As of 2013 Viz Media has released the manga in five different formats. Initially the manga was printed flipped and with English translations of the sound effects. Publication of English editions began in 1988 with the release of episodes from the story under the title Nausicaä of the Valley of Wind in the "Viz Select Comics" series. This series ran until 1996. It consists of 27 issues. In October 1990 Viz Media also started publishing the manga as Viz Graphic Novel, Nausicaä of the Valley of Wind. The last of the seven Viz Graphic Novels in this series appeared in January 1997. Viz Media reprinted the manga in four volumes titled Nausicaä of the Valley of Wind: Perfect Collection, which were released from October 1995 to October 1997. A box set of the four volumes was later released in January 2000. In 2004 Viz Media re-released the seven-volume format in an "Editors Choice" edition titled Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind. In this version the manga is left unflipped and the sound effects are left untranslated.[46] Viz Media released its own deluxe two-volume box set on November 6, 2012.[47] The manga was also licensed in Australia by Madman Entertainment,[48] in Finland by Sangatsu Manga,[49][50] in France by Glénat,[51] in Spain by Planeta DeAgostini,[52] in Italy by Panini Comics under its Planet Manga imprint,[53] in the Netherlands by Glénat Benelux,[54] in Germany by Carlsen Verlag,[55] in Korea by Haksan Culture Company[56] and in Taiwan by Taiwan Tohan.[57] In Brazil it was initially published in July 2006 by Conrad Editora, before it ceased in March 2009 after only five volumes were released and since August 2022, it is being republished by Editora JBC.[58][59] Original edition

Perfect Collection

Deluxe edition

Related mediaFilmWhen serialization of the manga was underway and the story had proven to be popular among its readers, Animage came back on their promise not to turn the manga into an animation project and approached Miyazaki to make a 15 minute Nausicaä film. Miyazaki declined. Instead he proposed a sixty-minute OVA. In a counter offer Tokuma agreed to sponsor a feature-length film for theatrical release.[85] The film adaptation of Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind was released on March 11, 1984. It was released before Studio Ghibli was established, but it is generally considered a Studio Ghibli film. Helen McCarthy has noted that it was Miyazaki's creation of the Nausicaä manga " ... that had, in a way, started the actual process of his studio's development".[86] The film was released with a recommendation from the World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF).[87] In his retrospective on 50 years of Postwar Manga, Osamu Takeuchi wrote that, in an ironic twist of fate, the Nausicaä film had been playing in theatres at the same time as the 1984 anime adaptation of one of the illustrated stories Miyazaki had grown up reading, Kenya Boy, originally written by Soji Yamakawa in 1951. Takeuchi observed that the release of its inspirational predecessor "would have been devoured" by Miyazaki's Nausicaä in a competition of the two works. He went on to note that, in spite of a brief Yamakawa revival around that time, the media for story telling had progressed and a turning point in time had been passed.[88] The story of the Nausicaä film is much simpler than that of the manga, roughly corresponding to the first two books of the manga, the point the story had reached when film production began.[38] In his interview for Yom (1994) Miyazaki explained that he worked from the precept that a film requires an opening and a closing of the story. He stated that, within the confines he set for closing the story, he took the film's narrative up to Nausicaä's "Copernican turn (コペルニクス的転回, koperunikusutekitenkai)", which came after the character realises the nature of the Sea of Corruption.[89] There are significant differences in plot, with more locations, factions and characters appearing in the manga, as well as more detailed environmentalist themes. The tone of the manga is also more philosophical than the film. Miyazaki has Nausicaä explore the concepts of fatalistic nihilism and has her struggle with the militarism of major powers. The series has been interpreted from the views of utopian concepts, as well as religious studies.[90] In The Christianizing of Animism in Manga and Anime, Eriko Ogihara-Schuck conducted a comparative analysis of the religious themes in the manga and the film. Ogihara-Schuck wrote that Miyazaki had started out with animistic themes, such a belief in the god of the wind, in the early chapters of the manga, had conflated the animistic and Judeo-Christian traditions in the anime adaptation, but had returned to the story by expanding on the animistic themes and by infusing it with a non-dualistic worldview when he created additional chapters of the manga, dissatisfied with the manner in which these themes had been handled for the film. Drawing on the scene in which Nausicaä sacrifices her own life, in order to placate the stampeding Ohmu, and is subsequently resurrected by the miraculous powers of these giant insects, Ogihara-Schuck notes that "Japanese scholars Takashi Sasaki and Masashi Shimizu consider Nausicaä a Christ-like savior, and American scholar Susan Napier considers her as an active female messiah figure". Ogihara-Schuck contrasts these views with Miyazaki's own belief in the omnipresence of gods and spirits and Hiroshi Aoi's argument that Nausicaä's self-sacrifice is grounded on an animistic recognition of such spirits. Ogihara-Schuck quotes Miyazaki's comments in which he indicated that Nausicaä's self-sacrifice is not as a savior of her people but is a decision driven by her desire to return the baby Ohmu and by her respect for nature, as she is "dominated by animism". Ogihara-Schuck concludes that in many of his later films, much more than in the anime version of Nausicaä, Miyazaki expressed his own belief in the animistic world view and is at his most direct in the manga by putting the dualistic world view and the animistic belief in tension and, through Nausicaä's ultimate victory, makes the animistic world view superior.[34] No chapters of the manga were published in the period between the July 1983 issue and the August 1984 issue of Animage but series of Nausicaä Notes and The Road to Nausicaa were printed in the magazine during this interim period.[38] Frequently illustrated with black and white images from the story boards as well as colour illustrations from the upcoming release of the film, these publications provide background about the history of the manga and development of the film. 1984 was declared The Year of Nausicaä, on the cover of the February 1984 issue of Animage.[91][92] OtherSeveral other Nausicaä related materials have been released. Hayao Miyazaki's Image Board Collection (宮崎駿イメージボード集, Miyazaki Hayao imējibōdo-shū) contains a selection from the sketchbooks Miyazaki created between 1980 and 1982 to record his ideas for potential future projects. The book was published by Kodansha on March 20, 1983.[93] The Art of Nausicaä (ジ・アート・オブ 風の谷のナウシカ, Ji āto Obu kaze no tani no naushika) is the first in the art books series. The book was put together by the editorial staff of Animage. They collated material that had previously been published in the magazine to illustrate the evolution of Miyazaki's ideas into finished projects. The book contains reproductions from Miyazaki's Image Boards interspersed with material created for the film, starting with selected images related to the two film proposals rejected in 1981.[94] The book also contains commentary of assistant director Kazuyoshi Katayama and a summary of The road to Nausicaä (ナウシカの道, naushika no michi). It was released by Tokuma Shoten on June 20, 1984.[95] Haksan released the art book in Korean on December 29, 2000.[96] Glénat released the art book in French on July 7, 2001.[97] Tokuma Shoten also released the contents of the book on CD-ROM for Windows 95 and Macintosh, with the addition of excerpts from Joe Hisaishi's soundtrack from the film.[98][99] The Art of Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind: Watercolor Impressions was released by Tokuma Shoten on September 5, 1995. The book contains artwork of the manga in watercolor, a selection of storyboards for the film, autographed pictures by Hayao Miyazaki and an Interview on the Birth of Nausicaä.[100] Glénat released the book in French on November 9, 2006.[101] Viz Media released the book in English on November 6, 2007.[102] Viz's version of the book was released in Australia by Madman Entertainment on July 10, 2010.[103] In 2012, the first live-action Studio Ghibli production, the short film Giant God Warrior Appears in Tokyo, was released, which shares the same fictional universe as Nausicaä.[104][105] A kabuki play adaptation, covering the events of the movie, was performed in December 2019.[106][107] ReceptionIn 1994, Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind, received the Japan Cartoonists Association Award Grand Prize (大賞, taishō), an annual prize awarded by a panel of association members, consisting of fellow cartoonists.[108][109] The manga has sold more than 10 million copies in Japan alone.[108][110] After the 1984 release of the film adaptation, sales for the manga dramatically increased, despite the plot differences between the two works.[111] In the spring of 1994, shortly after serialization had concluded, a combined total of 5.27 million Nausicaä tankōbon volumes had already been published. At the time Volumes 1 through 6 were in print. Volume 7 was not released until January 15, 1995. By 2005, over 11 million copies had been released for all 7 volumes combined.[112][f] In December 2020, it was announced that the series had more than 17 million copies in circulation.[115][116] Nausicaä was included by Stephen Betts in the comic book–centered reference book 1001 Comics You Must Read Before You Die, who said of the series:

Setre, writing for Japanator, said "Nasuicaa [sic] is an amazing manga. And no matter what you may think of Miyazaki this story deserves to be read. It has great characters (some of which could star in their own series), a great sense of adventure and scale, and an awesome story."[118] In his July 14, 2001, review of Viz Media's four volume Perfect Collection edition, of the manga, Michael Wieczorek of Ex.org compared the series to Princess Mononoke stating, "Both stories deal with man's struggle with nature and with each other, as well as with the effects war and violence have on society." Wieczoek gave a mixed review on the detail of the artwork in this, 8.08 in × 5.56 in (20.5 cm × 14.1 cm) sized, edition, stating, "It is good because the panels are just beautiful to look at. It is bad because the size of the manga causes the panels within to be very small, and some of these panels are just crammed with detailed artwork. That can sometimes cause some confusion about what is happening to which person during an action scene."[46][119] The Perfect Collection edition of the manga is out of print.[120] In his column House of 1000 Manga for the Anime News Network (ANN) Jason Thompson wrote that "Nausicaa is as grim as Grave of the Fireflies".[120] Mike Crandol of ANN praised the manga stating, "I dare say the manga is Hayao Miyazaki's finest work ever—animated, printed, or otherwise—and that's saying a lot. Manga allows for a depth of plot and character unattainable in the cinematic medium, and Miyazaki uses it to its fullest potential."[121] Pamela Gossin and Marc Hairston drew parallels between the Nausicaä story and On Your Mark, the music video Miyazaki created for the Japanese duo Chage and Aska. They interpreted the release of the winged girl at the end of the music video as Miyazaki setting free his character.[122] Miyazaki started creating On Your Mark the same month the seventh volume of the Nausicaä manga was released.[123] Kyle Anderson of Nerdist describes the setting as a steampunk post-apocalypse.[124] Philip Boyes of Eurogamer describes the technology in Nausicaä and Castle in the Sky as dieselpunk.[125] Notes

Citations

Sources

External links

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||