|

Milan Ressel

Milan Ressel (1 December 1934, Ostrava - 16 July 2020, Prague) was a Czech painter, printmaker, illustrator and restorer. LifeMilan Ressel was the son of Alfred Ressel, a Czechoslovak army officer who fled with his entire family to England via Hungary, Yugoslavia and France under dramatic circumstances at the turn of 1939/1940. As a major general, he commanded the artillery of the 1st Czechoslovak Army Corps in the Soviet Union since 1944.[1] Milan's older brother Fred enlisted in the British Army in 1944 and took part in the siege of Dunkirk. After the war the family returned to Czechoslovakia. His father was discharged from the army in the early 1950s and worked for a year and a half in the coal mines in Ostrava, then in Prague car repair shops and in an advertising company.[2] As a young boy Milan Ressel experienced the heavy bombing of London at the turn of 1940–1941, and his wartime experiences and his personal acquaintance with English literature for the young later influenced his work. After returning to Prague, he studied at the Higher School of Arts and Crafts in Prague (1949-1953) and from 1953 to 1959 at the Academy of Fine Arts in Prague with prof. Miloslav Holý, Karel Minář, Karel Souček. His friends included Karel Nepraš, Bedřich Dlouhý, Jaroslav Vožniak and Theodor Pištěk. He was a founding member and first goalkeeper of the Paleta vlasti hockey club and a member of the Association of Prague Painters. Since the 1970s, he has been a freelance artist, comic book creator, illustrator, graphic designer and mural restorer.[citation needed] Milan Ressel lived and worked in Prague and Středokluky near Prague. WorkIn the 1960s, he belonged to the circle of artists who devoted themselves to informel, and his free work was influenced by his friendship with artists from the Šmidra group (Koblasa, Nepraš, Dlouhý, Vožniak). The search for the artist's distinctive style was shaped between an inclination towards classical painting and the need to experiment. His abstract paintings from 1965 to 1966 contain hints of real objects and do not lose touch with the sensory world.[citation needed] In the second half of the 1960s he devoted himself almost exclusively to drawing. From smaller formats, he gradually worked his way up to monumental compositions. His utopian illustrations, which are close in content to Ray Bradbury's science fiction, are based on rational reflections on the real prospects of civilization and on the artist's sheer imagination.[3]

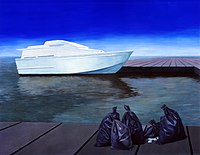

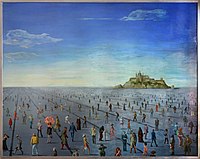

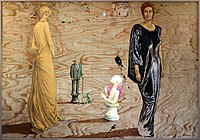

Ressel does not succumb to the fascination of the development of technology, but he does conjecture its effects on the devastation of nature and on the life of contemporary man. The drawings, with their abundance of minute detail, depict a world full of uncertainty and warning signs of possible self-destruction through war catastrophy or over-exploitation of nature. They express a certain anxiety about the cold modern architectures and industrial networks that increasingly surround nature. His compositions juxtapose the earthly and the cosmic, the ephemeral and the permanent, the vegetative and the organic with the technical and the inanimate. He acknowledges beauty and magical appeal to the world of machines and technology, which is a projection of human dreaming of distant worlds. He sees them as a natural part of reality and rather seeks the possibilities of mutual symbiosis and harmony.[4] In 1969 he accepted the offer of editor-in-chief Jiří Bínek to draw comic strips based on scripts by Ludvík Souček (Ten-eyed, Kraken)[5] for the youth magazine Ohníček.[6] He was offered another job by the editor Vlastislav Toman, who, in the temporarily freer atmosphere of the late 1960s, pushed the comic strip The Adventures of John Carter into the ABC magazine. In 1973 he illustrated Ludvík Souček's science fiction short stories The Interest of the Galaxy and in the 1980s he illustrated Jules Verne's book The Secret of Wilhelm Storitz (Mladá fronta, 1985) and Svatopluk Hrnčír's Země Zet (1990). Some of Ressel's comic strips are considered classics of the genre.[7] During the normalization he also made his living as a restorer. In the 1980s Milan Ressel returned to painting. Compared to his drawings, his paintings show a simplification of pictorial composition and an open space that invites free play of imagination. The basic realism of colours and forms is preserved, but there are different patterns that are beyond the visual experience of the real world. Most of the paintings are composed as a stage space set in a landscape, bordered by backdrops of trees, architecture or rocks. The artist reconsiders the ordinary relations of reality according to the logic of dreams and explores the psychic resonances of unexpected encounters, confronting technology and nature with each other and being inspired by the mystery of associations. The relativization of spatial relations and the "mannerist" use of perspective are also means of evoking an atmosphere of fiction. There are frequent quotations of works by other artists in new contexts (Bosch, Gaudí, Moore, Vyšší Brod (Hohenfurth) cycle).[citation needed] The space of the paintings is impersonal and "depopulated". The human trace appears in them through various references, but the figure appears in Ressel's paintings only from the mid-1990s onwards. In the composition This Is Us (1996), the figures emerge from the painting onto the stage in the foreground, but they are all deliberately static, and the ambiguity of the content is confirmed by the artist's static fixation of two figures on sticks stuck into the carpet.[citation needed] Milan Ressel depicts reality without imitating it. His painting is built as much on spontaneity as on an intellectually meditative component.[4]

Restoration work (selection)

Illustrations (selection)

Representation in collections

Exhibitions

References

SourcesCatalogues

External links |

||||||||||||