|

MetroMoves

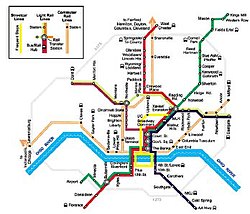

MetroMoves was a 2002 proposal by the Southwest Ohio Regional Transit Authority (SORTA) to expand and improve public transportation in the greater Cincinnati metropolitan area.[1] The 30-year vision included the addition of light rail lines, commuter rail lines, streetcars in the downtown area, and expanded bus routes.[2] When put to a vote the citizens of Hamilton County rejected the proposal by nearly a 2-to-1 ratio, 68.4% to 31.6%.[3] HistoryCincinnati transit planners began advocating light rail in 1993 when the Ohio-Kentucky-Indiana Regional Council of Governments (OKI) recommended a light rail feasibility study for the area along Interstate 71.[4] In 1998 a solution was adopted to build a 19-mile rail line that stretched from Cooper Road in Blue Ash to 12th Street in Covington.[4] The line would then form a backbone for subsequent rail lines to connect communities in the region.[4] MetroMoves began in 2000 as a plan to improve the city's bus system, but it was expanded to include the rail lines from the 1998 solution.[5][6][7] The complete plan was estimated to cost $4.2 billion, with the Hamilton County portion costing $2.6 billion for the rail lines and another $100 million for the expanded bus lines.[1] Of Ohio's $2.7 billion, half was to be paid by the federal government, a quarter by the state of Ohio, and the last quarter by a one-half cent Hamilton County sales tax levy.[1][8] In other words, about $39.50 per year per Hamilton County resident.[5] Commuter rails to Lawrenceburg, Middletown, Milford, and Hamilton would only be built if the surrounding counties could raise $1.02 billion to help pay for the lines.[5] The light rail portion was estimated to take 30 years to complete,[1] with the Covington-Blue Ash line scheduled to open in 2008.[4] Several public figures opposed the plan, including Mayor Charlie Luken and Congressman Steve Chabot—the latter of whom referred to the plan as a "boondoggle."[4] Mayor Luken accused SORTA of using tax payer money to illegally promote a ballot issue,[9] but SORTA argued that they were obligated to promote public transit and educate its citizens about possible options.[10] Additionally, there were concerns that citizens would be "double taxed" because SORTA already had an earnings tax,[11] and that federal funding would be low due to the highly competitive "New Start" program. Opposition to MetroMoves was led by a group called Alternatives to Light Rail Transit (ALERT). They argued that light rail is not workable over the long run, that highway systems are the lifeline of most businesses in the region and in the country, and that a study showed MetroMoves would have an insignificant effect on traffic congestion.[12] Others opposed MetroMoves because they didn't like the price tag, thought construction would disrupt neighborhoods, or they simply favored other transit options.[4] Proponents of MetroMoves argued that the new system would create 36,000 new jobs, spark new development, connect 300,000 existing jobs that do not have transit, save the TriState $85.1 million in gas and other auto-related costs, and eliminate much of the need for bus passengers to go into downtown to transfer lines.[5][12] The new transit plan was backed by Procter & Gamble, Fifth Third Bank, the Sierra Club, and the League of Women Voters.[13][14] A few weeks before Election Day $331,000 was raised to help promote MetroMoves, while ALERT raised less than $6,000.[14] During this time both sides participated in numerous public debates, where both reiterated the same arguments and accused each other of distorting the same set of facts to their advantage.[3] Additionally, citizens were reminded that Paul Brown Stadium opened $52 million over budget in 2000,[5] which was also funded by a half-cent tax levy.[15] On November 5, 2002 the tax levy, known as "Issue 7," was rejected by 68.4 percent of Hamilton County residents.[3] MetroMoves received the most support in Clifton and Avondale, but received the strongest opposition in suburbs such as Indian Hill, Madeira, and Wyoming.[16] Because of the way federal funding for public transit works this meant the plan could not be reconsidered for at least another five years.[16] There was a chance the project could bypass this by putting MetroMoves back on the ballot in the spring, but the CEO of Metro said, "there is nothing that leads me to believe today that things will change significantly in the public's mind over the next four to five months."[16] In 2003 the Ohio Elections Commission found ALERT guilty of using a false statement in an anti-MetroMoves television ad that ran during the 2002 fall campaign.[17] The ad stated that the Federal Transit Administration (FTA) rated the MetroMoves plan as one of the worst in the country, but the FTA said it does not rate transit plans against one another.[17] Regardless, later that year Stephan Louis, the leader of ALERT, was chosen as a member of SORTA's board.[17][18] In 2008 interest was renewed in MetroMoves due to a 4% system-wide increase in Cincinnati bus ridership when compared to 2007.[8] The bus ridership increased as high as 24% and 17% on some routes from April 2007 to April 2008.[8] As of July 2008 there were no plans to put either MetroMoves or a new transit plan on the ballot, though support is reportedly growing.[8] When SORTA's light rail plan failed in 2002, gas prices were at $1.42 a gallon and support from public leaders was expected to be much better.[8] PlanLight railThe regional rail plan was developed by SORTA, OKI, the Transit Authority of Northern Kentucky (TANK), and Hamilton County.[19] Liberty, Brighton, and Hopple stations were originally built in the 1920s as part of the unfinished Cincinnati subway.[20]

See also

References

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||