|

Madonna and business

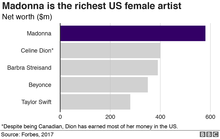

American singer-songwriter and businesswoman Madonna received significant coverage by business journalism, becoming the first solo entrepreneur woman to grace a Forbes cover (1990). She started some enterprises in her career, including Maverick and its subdivision Maverick Records. She was one of the first women in music to have established an entertainment company and a record label. In its early years, Maverick Records became the highest-grossing artist-run label. Her entrepreneur's profile became visible to her public image in her first decades, receiving praise, although it was the only role recognized by many of her critics. Despite the ever-evolving nature of business, Madonna received immediate and retrospectively interest from marketing, management and businesses communities. She was discussed in related themes, including capitalism, marketing strategies and consumerism. Called the "Material Girl", Madonna also epitomized the consumer ethos of the 1980s and beyond, for which she attained both cultural praise and severe criticisms. She was considered the ultimate in crass commercialism and the epitome of banal consumerism. Madonna has been continually considered by many critics as only a marketing product. Furthermore, Madonna is also credited with pioneering some brand management strategies, and for helping shape music business. Madonna also served as a role model of self-actualization and reinvention, inspiring expressions coined in the 2000s such as the "Madonna effect" by business professor Oren Harari and the "Madonna-curve" used by a think tank author for NATO. Commercial and financially, Madonna became for a short-span the highest-grossing woman in media and ended as the highest-earning female musician of the 20th century. Into the 21st century, Madonna continued as the richest woman in music until being surpassed in 2019. She also became the first female artist to have earned more than $100 million in a single year (2009), and scored then the highest-earnings for a female pop star (2013). Madonna has appeared as Forbes top-earning female musician a record 11 times, spanning four separate decades. Culturally, Madonna's figure impacted tourism of some places, including Belize's San Pedro Town thanks to "La Isla Bonita", and during the 2000s in Israel which lead her being praised due to Second Intifada crisis. Critical backgroundCommunity interest

—The Madonna Connection (1993).[2]

For many reasons, Madonna's semiotics extended to marketing, academic, management and business communities over the years. During the height of her career, media scholar Douglas Kellner considered "one cannot fully grasp the Madonna phenomenon without analyzing her marketing and publicity strategies".[3] Andrew Morton commented her "success has certainly impressed the business community".[4] Various authors working in the Madonna studies, focused its developments in marketing strategies and consumer culture.[5][6] She also became a "central image" in the studies of commercialism according to authors of The Madonna Companion: Two Decades of Commentary (1999),[7] and embodied capitalism to intellectuals according to Ann Power in 1998.[8] In 1995, professor Suzanna Danuta Walters explains Madonna was generally represented as a "personification of commodity capitalism".[9] For decades, businesses also used Madonna as a role model of self-reinvention.[10] Stephen Brown (University of Ulster marketing professor) seen her case as "relevant" to the consumer research community when analyzed her in 2003.[11] In the early 2000s, Kelley School of Business considered her more than a "pop cult icon" describing "she is someone every can learn from", although counter to conventional to 4Ps variety.[12] Effects on Madonna's public imageRegarding critical perceptions, Madonna's business profile became visibly to her public image, leading her critics to have a "popular answer" when it comes to define her, that "she's done it through sheer business savvy", according to Jennifer Egan in 2002.[13] In fact, Ludovic Hunter-Tilney commented for Financial Times in 2008, that for her critics she is right to describe herself as a businesswoman but wrong to call herself an artist.[14] According to professor Robert Miklitsch from Ohio University in From Hegel to Madonna: Towards a General Economy of Commodity Fetishism (1998), she is "largely a story about publicity and marketing".[15] Professor Ann Cvetkovich similarly considered her a product of "intense marketing and public relations campaigns", but also reflects that the relationships between her production and reception by world audiences "must be articulated".[16] List of associated enterprises and brands

CharitySome endorsementsAreasBusinesswoman roleMadonna has started various enterprises.[19] She became one of the first female celebrities to have ever established an entertainment company and a record label,[20][21] and became one of the first female CEOs in the industry.[22] Madonna received positive commentaries in the community; she is "herself a corporation, and a rather diverse one" wrote Miklitsch.[17] Similarly, Colin Barrow a visiting scholar at the Cranfield School of Management described her as "an organisation unto herself",[23] and Kevin Sessums also described her "a corporation in the form of flesh".[24] Despite positive commentaries, Madonna debuted in an era when most entertainers avoided labels of "manager" or "businesswoman",[25] marked by a cultural perception at that time of art and commerce. American political analyst Matt Towery, described in 1998: "Madonna never tries to portray herself as a corporate manager or captain of industry".[26] She herself downplayed her role, saying "I don't think is necessary for people to know that".[27] Madonna was also quoted as saying: "I'm very flattered that everyone thinks I'm such a good businesswoman, but I think that to say that I'm a great manipulator, that I have great marketing savvy is ultimately an insult, because it undermines my power as an artist".[28] On the contrary, her profile became notorious at that time and her entrepreneurial talent begun labeled "legend" to the public perception and insiders.[29] In 2007, Billboard explained Madonna's CEO "has a reputation as being a tenacious executive as ubiquitous as her music".[21] Publicity and endorsements In her early career, Madonna also earned a reputation of being a "calculating businesswoman",[30] which led The Canberra Times to describe it as a "crucial difference" between her and other American industry fellows.[25][30] She refrained from commercializing her brand with all sorts of products, and which Forbes commented that fellows such as Bill Cosby and Michael Jackson who "eagerly hawk products, Madonna refuses to do so [...] more likely she fears it might sully her image as an artist".[30] On the other hand, her tactics of marketing and publicity were especially noted during her first decades of career. She was described as a "supreme expert on marketing" by The Daily Gazette in 1997.[31] Although some considered she "rigid control of her own publicity",[32] British novelist Martin Amis also said that she understands "her publicity gets publicity".[33] Nekesa Mumbi Moody from Associated Press wrote in 2006, that "Madonna certainly has been the embodiment of the adage, 'there's no such thing as bad publicity'".[34] In 1990, Richard Harrington from Washington Post called her "Our Lady of Perpetual Hype".[35] He cited Paul Grein from Billboard who also considered the singer a "very smart and very shrewd artist", whose generates a lot of publicity, interpreting it as her "key to staying on top". Grein concludes "her career events are as carefully choreographed as the GOP convention".[35] Branding Madonna is one of the first celebrities to protect her name as trademark.[36] According to Irish Examiner, she did it in 1979 when still unknown.[37] Authors of Gen Z, Explained (2022), including Jane Shaw, held that "the 'selfmark' trend can be traced back to Madonna in the 1980s".[38] Madonna also impacted in her generation the usage of a one-single name. In 1987, Radio & Records noted an increase of female singers with one-name, while the phenomenon goes back beyond her, the magazine perceived an increase in the era, after singer's debut.[39] In 2022, American Songwriter magazine said: "If she didn't invent the one-name legacy then she sure made it real".[40] Various branding experts appreciated her ability to expand her brand, including marketing executive Sergio Zyman and author Armin Brott agreed in The End of Advertising as We Know It (2003), "unlike almost anyone else in her business" she has an "uncanny ability to retool" her brand further adding "no one repositions herself as well —or as frequently— as Madonna".[41] TrendsMadonna was recognized in the community and media as a trend-setter, and "widely perceived to be on the cutting edge" for that reason, according to authors of Emotionally Intelligent Leadership (2009).[42] In 2008, Rashod Ollison from The Baltimore Sun described it as her "career hallmark".[43] A commentator said in 1998 for The Vancouver Sun, "Madonna is to trend-surfing what Stephen Hawking is to cosmology".[44] According to business theorists Jamie Anderson and Martin Kupp for London Business School in 2006, Madonna is "one of the world's first artists to bring this approach to the music industry".[45] Professor and editor Popy Belasco even named her the "first coolhunter in history".[46] Linda Mihalick, professor in the Merchandising department at University of North Texas, commented "her ability to set trends became unrivaled".[47] Marketing expert Roger Blackwell explained "she becomes the conduit", introduction and acceptance of a wide range of trends in areas from fashion to expression, dance, lifestyle and more.[48] However, a turning point occurred during the release of her album Hard Candy (2008) and has since continually deemed as a follower of trends.[43][49] Legacy

Entertainment Weekly (1999)[50]

Madonna has been noted as a self-marketer. Her performance at the inaugural MTV Video Music Awards in 1984, was called a defining moment in her career as she emerged as a self-made star, according to The Greenwood Encyclopedia of Rock History (2006),[51] while Bitch magazine highlighted it as a marketing strategy and a defining moment for women in rock.[52] Overall, Irish Examiner commented in 2018 that "she broke new ground, harnessing and marketing herself".[37] Ohio State University scholar David Bruenger held that "she pioneered brand management strategies".[53] She is credited for helping transform "self-reinvention" and "multiple identities" into a business strategy in her industry according to Brown.[54] In 2007, she was included among Billboard's Power Players recognizing women in the entertainment industry who "have made an important mark on the music business".[21] In 1992, a contributor from The Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing, describes Madonna as a signifier of changing "world's views" of the boundaries between "music, entertainment, and business", along with other figures like Bill Gates with similar impacts, such as world's views on information-processing.[55] Similarly, hispanic scholars in Bitch She's Madonna (2018), grant her also a notable role for help shaping music businesses as "we know it".[56] In 1986, The Sunday Times commented with Madonna's spurt to fame, "new heights have been scaled or new depths plumbed".[57] The advent of Madonna usher the "phenomenon of star as multimedia impresario" considered Gerald Marzorati.[13] In both 1990s and 2000s, she signed some of the largest music deals, and some commentators seen them as influential for helping shape music businesses; Madonna's 1992 deal with Warner, was according to BBC Worldwide in 1994, "seen by many as the symbol of the kind of new relationship between a global media star and the moneymen".[58] Madonna became the founding artist in Live Nation's division, "Artist Nation" in 2007.[59] Described as a "radical deal" by BBC, they referred she was the first "major star" to choose an all-in-one agreement with a tour company over a traditional record deal.[60] In HumanCentric (2020), analyst Mike Saunders largely explored its impact, calling the deal a "milestone" that clearly helped change the way of many aspects in the concert industry, a sector that would later become a leading source of music revenues.[61] In Peer to Peer and the Music Industry (2010), Matthew David also explored Madonna's move as the "first big name" further calling it "significant".[62] Madonna's forays within the wireless world would also impacted the medium, including during the release of American Life in 2003, as claims Rick Mathieson in Branding Unbound (2005).[63] Previously, in 2000, The Business Times called her the "epitome of m-commerce".[64] Cultural impactAccording to Encyclopædia Britannica in 2009, Madonna "achieved levels of power of control [that were nearly] unprecedented for a woman in the entertainment industry".[65] Biographer Chris Dickers noted how she was referred to as "the most successful woman in the history of the music business".[66] For instance, Deutsche Welle in its English version called her "music business' most successful woman" in 2018.[67] Two decades prior, The Daily Telegraph commented in 1998: "Madonna is arguably the most successful businesswoman in the entertainment industry (her only rival for the title being Sherry Lansing, chairman of Paramount)".[68] Madonna's business profile transcended music industry, as she began referred by various corporations and businesses as a role model, mainly for self-reinvention.[10] Lyve Lab's director at Israel and Singapore named her a role model in early 2023.[69] According to Alfons Cornella from Deusto Business School in 2007, node used the phrase "this is a Madonna company" to define a company capable of reinventing successively.[70] Spanish Socialist Workers' Party also recognized Madonna's reinvention in 2015.[71] Years later in 2017, Uruguayan newspaper El Observador, also noted how a company used Madonna's reinvention as a central theme.[72] Expressions coined

RecognitionDuring her career, Madonna was referred variously by media, including "Queen of Marketing", "Queen of Rebranding", "Queen of Branding" and "Queen of Trends".[78][79][80][81] In early 1990, Jon Pareles called her "Queen of Multimedia Promotion".[82] In the mid-2000s, MuchMusic named her "the world's top trend-maker".[83] In the 1990s, scholar Douglas Kellner called her as "one of the greatest PR machines in history".[15] Various called her a "marketing genius", including Brown in 2004.[11] A contributor from Slate magazine in 1999, listed as the "Madonnas" of the age of stock market, and celebration of the entrepreneur to individuals from Bill Gates to Steve Ballmer.[84] American accountant Sharon Lechter, in 2014, noted that she has received acclaim for her role as a businesswoman in media.[85] She received positive commentaries both immediate and retrospectively. Dan Bigman from Forbes noted how in early 1990s, they deemed her as one of "shrewdest businesswomen we'd ever seen".[30] She became the first solo female entrepreneur on a Forbes cover (1990) according to themselves.[1] In 2021, Maggie McGrath from the publication mentioned that moment in an article discussing women participation in magazine's history.[86] Madonna was then considered "America's smartest businesswoman" in the community,[23] with editor of Profiles of Female Genius (1994), explaining it was an unusual treatment at that time, because he considered Forbes as part of the bastion male capitalism system.[29] In 2013, British entrepreneur Vince Stanzione, referred to her as "one of the smartest self-made businesswomen in this century and last".[87] In 2014, Gabriela Pedranti of the Istituto Europeo di Design acknowledges her business role, considering her a productive and intelligent multimedia-digital platform itself.[88] In 2006, business theorists Jamie Anderson and Martin Kupp for London Business School, concluded she is a "born entrepreneur".[45] Madonna as brandMadonna's brand was discussed as a cultural product or amid consumer culture over years. By 1998, Ann Powers wrote for The New York Times that in last years, her "symbolic impact wane".[8] Alone in the 21st century, during the release of American Life in 2003, The New York Times also addressed difficulties amid younger generations in the United States.[89] Also, a researcher cited by various media publications in 2016, discussed how her brand has significantly lost influence, although he called the singer a "legacy act".[90][91]  Others have estimated her brand both retrospectively and well over the course of the 21st century. In Understanding Digital Culture (2011), Vincent Miller elaborates that she is a "marketable product" due to her popularity and that even if one can download her music for free, "as a product still has marketable value". He later said that her "decline or rise in value has more to do with cultural factors that her scarcity".[93] Economist Robert M. Grant, studied her case in 2008, praising her longevity in an "intensely competitive, volatile world of entertainment".[94] In 2012, José Igor Prieto-Arranz from University of the Balearic Islands described her as a generational household name for different targets.[95] Writing for business magazine Campaign in 2018, AARP's Patricia Lippe Davis considered her case notable within a visible target on the market, women over 60.[96] In 2023, BBC Music correspondent Mark Savage, noted a "resurgence" last year thanks to platforms such as TikTok.[97] In Brazil, one of Madonna's primary markets, a 2024 research by Chartmetric revealed that Generation Z was her primary audience, followed by people in the 25–34 age range. This information was reported by Folha de S.Paulo.[98] Academics from Warwick Murray (2006) to business theorists such as Michael Czinkota and Ilkka Ronkainen (2013), called her a "global brand".[99][100] Willie Cameron from Loch Ness Marketing acknowledges Loch Ness' global brand lumping with others, including Madonna, by saying in 2014: "It's as big as Coca Cola, Madonna, Elvis Presley. It's global".[101] Furthermore, in The Experience Effect (2010), author Jim Joseph considered her a "quintessential brand" further arguing she is "perhaps the epitome of celebrity marketing and celebrity branding".[102] Similarly, Michael Levine commented about her 20-years plus career, that she "bucked every rule of branding and still manage to become the most well-known, well considered brand in the entertainment business".[103] In 2015, business magazine Fast Company labeled her "the biggest pop brand on the planet".[104] In 2020, Journal of Business Research collaborators estimated her as "probably the most successful female music artist ever in terms" that include "brand recognition".[105] Cultural aspectsBackgroundCross referential socio-cultural aspects were also remarked on by community, academics and media alike. Back in the 1980s, journalist Steve Anderson speaks of "Madonna's resonance in the minds of the public", saying she become a "repository for all our ideas", including money.[106] According to Theodore Koutsobinas in The Political Economy of Status (2014), media celebrities like Madonna were "widely seen as symbols" of the Great Moderation period.[107] For a notable portion of public, including authors, she became a paradigm of the Reaganomics era,[108] and also for the Thatcherism in the United Kingdom.[109] Thomas Ferraro granted her an "important" cultural role as a whole, at least for young public in the 1980s, defending his point by saying she was a "miracle worker, and wonder woman", the "faith healer" of Reagan's divide and-conquer America.[110] Perspectives To many authors, Madonna embodied the materialism bloosed in the 1980s during the emergence of new technologies of the era, as economist Jeremy Rifkin in The Empathic Civilization (2010), said she "capture the spirit of the age when she proclaimed to be a Material Girl".[111] According to Brown, her "Material Girl" persona was held up as an embodiment of the "Greed is Good" 1980s decade.[11] Catherine Gourley detailed how the song resonated with young women across the United States. As girls wanted more than equal opportunity in the workplace, and being a "material girl" was more rewarding than being feminist.[112] Author Nicholas Cook, however, said its influence was seen later among such diverse groups such as gay community, women, straight people and academics.[113] After having influenced yuppie culture with a monetary hedonism, Ann Powers for The New York Times in 1998 noted her turning into spirituality, saying were been "scrutinized as signs of a new style of growing up".[8] Madonna was described with having a "street-smart attitude",[114] while Barrow commented her business skills included "planning, personal discipline and constant attention".[23] Madonna was defined a workaholic, including by critics Camille Paglia and Gina Arnold.[115][116] In 2000, writer Warren Allen Smith explained many people of the 1990s spoke of Madonna as "the lady who work".[117] Henry Rollins referred "when you're sleeping, she is working".[118] Called "one of the hardest working and most disciplined of performers" by some publications, including The Guardian (2023),[119][118] others further called her as arguably "the hardest-working woman in the music business", including The Straits Times (2001).[120][121]

Madonna has also a reputation of being ambitious, described as "legendary".[123] It became a "common denominator" in her marketing analysis according to Roger Blackwell in 2004.[48] German cultural critic Diedrich Diederichsen explained she herself openly cultivated that legend.[124] In her early career, she was quote as saying: "I'm tough, ambitious, and I know exactly what I want. If that makes me a bitch, okay".[125] In updated views, during the 2010s she told Matthew Todd that her ambition was driven by feeling unloved after her mother's death,[126] and also told Alexis Petridis, that she just meant "I want to make a mark on the world. I want to be a somebody".[127] Different reviewers have interpreted her ambition variously ranged from negative to neutral. Madonna critic bell hooks, as pointed out scholars from Nordic Association for American Studies commented it was a "monetary and a global media ambition".[128] French scholar Georges-Claude Guilbert said that her ambition was also to try her hand at every art form.[129] Author Kay Turner felt she "made outrageous claims about her ambitions, but invited the world to join her in believing that dreams come true".[123] Similarly, Alina Simone wrote in Madonnaland (2016), that she "has never been anything but aggressively honest about her ambition".[130] American feminist Susie Bright commented that "she is considered too ambitious, and therefore too much like a man".[129] A contributor from website Death and Taxes, commented in 2014, that she has "changed society through her fiery ambition and unwillingness to compromise".[131] Authors of Strategic Marketing (2010), commented "she has created a rags-to-riches myth".[132] Madonna embodied the American Dream for many people and authors, with a special emphasis on women and as a self-made star. Writing for German newspaper Süddeutsche Zeitung in 2008, Caroline von Lowtzow commented she turned into a "female incarnation" of the "self-made man".[124] "Few figures in American life have manage to exert as much control over their destinies as she has, and the fact she has done so as woman is all the more remarkable", wrote Jim Cullen in 2001.[133] Although Madonna reflectiveness in American Life (2003) interrogate also the American Dream.[134] Commercial impactGlobal economy Madonna's corporate image reached a noteworthy global height through the early 1990s. During this period, she was described as "a valuable property in the world of international capital", as her value overseas was regarded double than her domestic one.[24] On this, American business writer Tom Peters praised her international numbers, commenting in 1993, she runs a "positive trade balance" leading him to describe it as part of a "new soft economy".[135] Madonna was ranked among U.S leading exports in 1992, which lead Walter Berns call her as one of the biggest American export items.[136] On that year, Spanish newspaper ABC even named her as the "most prolific, profitable and universal consumer object since the commercialization of Coca-Cola".[137] She was being called by others as "the most commercial singer of all-time" by this point, including Leo Tassoni.[138] In Madonnaland (2016), Alina Simone retrospectively commented: "Madonna isn't just a musician; she is the 'whole package' and a 'real' prophet of commerce. [...] One might even call her an artist of commerce".[130] Professor Roy Shuker in Understanding Popular Music (1994) commented she "must be viewed as much as an economic entity as she is a cultural phenomenon".[139] Author of International Communication and Globalization (1997), lumped Madonna along with Internet, Michael Jackson and other cultural motifs for paving the way the global economy.[140] American business writer Robert J. Samuelson, explored for The New York Times in 1991, the interchangeable growing aspects of a global economy, and titled his article "Madonna and the New Economic Order".[141] Tourism and economyMadonna's Colombian public street announcements for the MDNA Tour in 2012 Madonna has also contributed with temporary to nearly enduring pop-culture tourism around the world. A one-time event such as a concert benefit local tourism; for instance, during her The MDNA Tour (2012) in Colombia, moved unprecedented figures for a concert in Medellín, early predicted with three times of what the municipality spent throughout the year.[143] Similarly, Madonna's free concert at Rio de Janeiro's Copacabana Beach as part of her Celebration tour in May 2024, boosted city's economy and was called by some media as the "Madonna effect".[144] According to geopolitic author Parag Khanna, Madonna helped "put Malawi on the map".[145] In 2013, BBC compared how with Madonna, the country was "enjoying a boom in visitors" up 181% in the last seven years.[146] In 2018, Malawi Tourism Council (MTC) also acknowledges Madonna's inputs in a discussion with The Nation.[147] Similarly, in Issues in Cultural Tourism Studies (2015), Melanie Smith said after the release of Evita with Madonna, it "boosted the profile of Argentina in recent years".[148] Madonna's wedding with Guy Ritchie in late 2000, carried a media frenzy on Scotland no seen since a report about Loch Ness in 1933 according to Associated Press,[149] while authorities called the "Madonna effect" to the publicty she drew to Scottish Highlands.[150] "La Isla Bonita" is an example of an enduring impact. According to Minister of Tourism from Belize, the song have contributed to San Pedro Town's tourism.[142] During the 2000s, Madonna favored Israel's tourism, especially in the city of Safed. Her presence was praised amid the Second Intifada crisis,[151][152][153] producing Israeli tourism's major media coup when she declared Israel a safe destination.[154] Gideon Ezra, Ministry of Tourism was reportedly distribute photographs of Madonna's 2004 visit.[155] Sylvan Adams, the Israeli-Canadian billionaire who brought Madonna to the 2019 Eurovision Song Contest, expected the same as in previous years.[156][157] From 2017 to 2020, Madonna lived in Lisbon, Portugal. Portuguese and Spaniard media outlets credited her presence as a boost and help for Portugal's tourism industry, having found benefits in "luxury tourism" or real estate business, with a journalist from ABC calling it "the Madonna effect".[158][159] However, Bloomberg News also reported in 2017, how celebrities like Madonna caused home prices raise, worrying locals.[160] In 2018, the country won their first World Travel Awards for the World's Leading Destination. On the win, EFE commented both Madonna and Cristiano Ronaldo were two of leading ambassadors who made it possible.[161] In 2022, British Vogue editor Laura Hawkins called her "Lisbon's most famous expat".[162] Madonna's name has been also used in tourism sector in other ways. She was proposed also by organizations or individuals to promote tourism of locations such as La Palma (also called "La Isla Bonita"),[163] Turkey,[164] or Pacentro, Italy (the city of her paternal grandparents).[165] Director of Business Development for Telefónica used Madonna as example in 2017 for seeking a tourism sector free of bureaucratic procedures,[166] while MCI Singapore CEO, called Singapore as "Madonna of the Destinations" as "the country re-invents itself every few years" according to Singapore Tourism Board.[167] After an article published by South China Morning Post reporting that Madonna snubbed Hong Kong to perform a concert in the early 2010s, it turned into a "strong adverting selling point" for Hong Kong tourism industry. It was reportedly the Tourism Board used Madonna's example to asking the government to create a proper concert venue.[168] Warner corporationMadonna was particularly a successful act for WarnerMedia corporation during several years. During the height of her career, some called her as perhaps their "most effective corporate symbol" behind Bugs Bunny or its leading person,[169][17] including by Musician magazine.[170] An author explained they usually featured Madonna's picture prominently in their annual report.[169] At some point, Judson Rosebush and Steve Cunningham commented in Electronic Publishing on CD-ROM (1996) that she accounted for something like 20 to 33 percent of all record sales from Warner Communications, as well pointing out she was an influence for their stock.[171] Alone in 1986, WEA International reported an increase of 27% in revenues, then their largest recorded sum in 15 years and with Madonna having a leading role followed by Phil Collins.[172] Described by scholar Fred Goodman back then as "one of their biggest and most consistent-selling artists",[173] Michael Ovitz called Madonna as Warner Music's "hit machine".[174] Madonna's record label, Maverick Records also achieved commercial success in its early years. Once described as a "highly profitable" artist-run label, Madonna had an important role along Freddy DeMann in approving their signed artists.[175] In 1998, Ingrid Sischy from Vanity Fair deemed the label as one of the "few artist-involved entities in the business to have moved into big-league status".[175] The same year, Spin recognized it as "the most successful vanity label", while under Madonna's control, it generated well over $1 billion for Warner Bros. Records, more money that any other recording artist's label up that point.[176] Other industries and products Her advertising debut was made in Japan with a campaign for Mitsubishi Electric between 1986–1987. It helped to erase corporation's image of being "safe but bland" after researchers noted most Japanese no longer considered them a "conservative company".[177] Her campaign also led to Japanese agencies and advertisers to feature more musicians, invigorating the overall interest in using foreign celebrities in ads by that time.[177] Madonna also impacted other brands, including Vita Coco. According to UPI, she convinced a number of celebrities to invest in the company.[178] In a conversation to TheLadders.com in 2019, its founder explained how crucial was Madonna to have the brand growing up.[179] After Madonna's announcement on social media in 2010 promoting the water, the company received ten times their usual web traffic.[180] Short after, Vita Coco became the sales leader of coconut water in the U.S. with a 60% of market share at some point,[181] while publications like Reuters called it the "world's leading brand of coconut water".[182] Financial-targeted Spaniard newspaper El Confidencial, explores how the coconut water before Madonna, was only sold in ethnic food stores and other small locals.[183] Madonna also helped popularize a variety of other products, including Cosmopolitan cocktail, which was later frequently mentioned on the television program Sex and the City.[184] Earnings Madonna's own financial triumph was praised in her generation, coinciding when Forbes began tracking entertainer earnings in 1987; less common in her time, professor E. Ann Kaplan described in 1993, that she "has entered the public sphere as an entrepreneur earning a lot of money, something that is not considered natural for women".[185] Her consistency was acknowledged by Clifford Thompson in Contemporary World Musicians (2020), where wrote: Madonna "has been overwhelmingly successful on a financial level".[186] In Routledge International Encyclopedia of Women (2004), feminist scholars Cheris Kramarae and Dale Spender commented she achieved "the kind of financial control that women had long fought for within industry".[187] Called by Forbes, circa 2020s, as "one of the top pop divas of all time",[1] Madonna was reputed to be the highest-earning female performer of the 20th century.[188] Authors in On the Edge (1998), even called her as the "most financially successful female entertainer in history".[189] A decade later, in 2010, author Matthew David named her as well "the most profitable female performing artist of all time" in Peer to Peer and the Music Industry.[62] In the 1980s, she grossed an estimated $1 billion in products.[190] Madonna's spokeswoman, Liz Rosenberg, accounted at least $2 billion worldwide sales for her albums and music products by early 2003, according to The New York Times.[89] Madonna's image also helped others financially succeed. Stephen Jon Lewicki, director of Madonna's first film appearance, A Certain Sacrifice became "millionaire" after film's VHS distribution in 1985.[191] In 2018, Bloomberg News explained Tsuyoshi Matsushita from Japan, and founder of MTG Co. become in billionaire after gambling on Madonna and Cristiano Ronaldo.[192] In a conversation with Spin in 1998, producer William Orbit, said: "There are a lot of people depending on Madonna to maintain their livelihood".[193] Forbes' lists Madonna made appearance in four consecutives decades on Forbes' entertainer earning-lists, becoming the annual top-earning female musician a record 11 times. During several years running in the 20th century, she was blocked by only Oprah Winfrey, although she also became for a short-live period "the highest-grossing woman in entertainment" according to Forbes prior 1990.[196] Regarding female artists, Forbes themselves, pinpointed in the early 1990s the "rise fast and fade fast" of other contemporary female artists, while they said Madonna "nearly reach" their top for consecutive years.[30] However, it was until 2009 that she was able to be the highest-paid musician overall,[197] and until 2013, she became annual's highest-paid celebrity in media industry.[194] Madonna also topped their first inaugural "Cash Queens of Music" list in 2007.[198] In 2015, Madonna appeared at the inaugural list of Forbes's America's wealthiest women (originally America's 50 Richest Self-Made Women), as the top singer.[199] By 2017, Madonna was the second highest-ranked entertainer on the list, just behind TV personality Oprah Winfrey.[200] As of 2024, she was continually ranked since 2015, reaching her own highest "self-made score" at 9.[1]

Other earning listsIn March 1986, the New Sunday Times informed Madonna banked a then "straggering" $25 million in just one year.[215] Madonna was the top musician at some Billboard's Moneymaker lists, including in 2008 and 2013.[216][217] She also made appearance at some Sunday Times Rich List, including in 2002, where she was the top paid musician in Britain.[218] Money and earning recordsMadonna is the first female singer to earn more than $100 million in a single year. Madonna is believed to have once the largest recording contract for a short-time when she signed an agreement with Warner in 1992.[219]

Statistics and achievementsContradictory perspectivesCriticisms Madonna was often considered for critics as only a marketing product.[14] According to The Nation in 1992, Madonna was deemed by mainstream academics as a "talentless opportunist" and a "monster created by the publicity machine".[228] At that time, American journalist Michael Gross described her as the "world's most advanced human publicity-seeking missile".[229] Writing for Time magazine in 1994, Jamaican author Christopher John Farley commented that her career has "never really about music", while mentioned publicity.[230] "She's a product of the shopping-mall culture", once criticized Dave Marsh.[231] At some stage of her career, she became a flashpoint for advertisers.[232] Although it has also earned her sympathetic reviews and praise, she is also known for generating scandalmongering which lead an author to describe her as the "Warren Buffett of the shock market".[233][132] Therefore, some controversial moments in her career, were accused of publicity stunt, including Rebel Heart Tour's Australian gig, when Madonna accidentally exposed the 17-year-old Josephine Georgiou's breast in front of thousands,[234] her stage fall at the Brit Awards of 2015,[235] or her first adoption of Malawian children, David Banda in 2006 amid her Confessions Tour.[236] Some other focal criticisms remarked that she was known for "selling sex";[233] a 2008 cover of Vanity Fair highlighted that she "made her fortune selling sex".[237] On the other hand, Madonna's advertising posters for Rebel Heart was considered a controversial album cover for Hong Kong’s public transportation which caused to have included a warning label.[238] Madonna also garnered some criticisms for fads she propelled. Writing for The Conversation in 2016, University of Southern Queensland's lecturer, Susan Hopkins, said that she "pioneered a lot of cultural trends that didn't do average working women a lot of favour".[239] Some of her business moves were not well received by others; in Branding Unbound (2005), Rick Mathieson wrote that "Madonna was among the first global brand names to make advertising campaigns delivered to consumers' cell phones seem downright dope".[63] Blockbuster music deals of high-profile artists like Madonna, Michael Jackson, Prince or Barbra Streisand in 1992, was criticized by an editor from Telegraph Herald commenting "the goal wasn't to improve the music, it was to generate the most hype".[240] Upon announcement, her deal in 2007 with Live Nation met with some skepticism in the sector.[241] Pepsi controversyMadonna also became part of the Pepsi Generation with an advertisement in 1989.[242] Contemporary reception, including an article from Los Angeles Times, considered it as part of the Cola wars.[243] Her advertisement sparked an "extensive" coverage in a variety of "diverse arenas", including stock market circles, the show-business industry and tabloids according to James Robert Parish and Michael R. Pitts.[244] While some critics regarded it as a blockbuster sponsorship,[245][246] J. Randy Taraborrelli labeled her deal as one of the "biggest controversies in the history of corporate advertising's" related to pop music.[247] A contributor from Forbes considered that back then, the ad hurt the brand image and Pepsi lost millions of dollars.[245] Years later, Pepsi embraced the commercial uploading a shortened version on YouTube in 2023 as part of their 125th anniversary, while Madonna thanked them to re-aired the commercial.[248] Nonetheless, in 2018, Spanish critic Víctor Lenore described the commercial helped open the door to major endorsements in pop music.[249] Mary Gabriel similarly explored for Vanity Fair how its accompanied video "rewired Pop capitalism".[246] Consumerism and capitalism

Glenn Ward (2010).[250]

During the height of her career, Madonna largely exemplified the "globalization of American consumer culture".[251] Kristen Marthe Lentz was quoting as saying when it comes to Madonna, "suddenly everybody is a critic of capitalism".[252] To various reviewers she epitomized the consumer ethos of the 20th century, or the 1980s at least.[253][254] Akbar Ahmed wrote she was the "supreme product of the consumerist culture".[252] Madonna was also labeled as "the ultimate" in crass commercialism, the epitome of banal consumerism and a representation of the "worst excesses of commercial exploitation",[250][255] as John E. Seery reports, her critics considered her "a vulgar reflection of gimmicky American consumerist culture at its worst".[256] Writing for political magazine CounterPunch in 2019, Ramzy Barroud considered Madonna along with the Beatles and Coca-Cola as examples of "tools used to secure cultural, thus economic and political dominance".[257] In 1997, author Douglas Baldwin explained with Madonna's case, that some other people in fields like medicine receive very few rewards in relation to their contribution to society, and entertainers such as Madonna, earn much more than they contribute to it, although brought examples of public figures like philosopher Ayn Rand favoring free will of people entitled to spend "whatever they wish", which lead him to include examples of "expensive" tickets.[258] In 1993, Nirvana's vocalist Kurt Cobain nod how musical acts like Madonna charged a notable gap for ticket prices, compared to their case.[259] She also received internal criticisms by some for development costs, as it was the case of budgets for music videos; on the case, an article of Vanity Fair in 2000, referred that the success of Madonna and Michael Jackson, "sent video production costs spiraling, enraging record company executives and artists".[260] ResponsesOthers slightly objected some criticisms towards Madonna, or favored some points. Responding to a commentator whom said "Material Girl" reflected "the deterioration of Western values", Muslim scholar Sheikh Kabbani considered and responded "you have to be both material and spiritual [..] Madonna is giving people a kind of joy in their material life. You cannot say she is wrong".[261] On pair with criticisms, Brown also noted in 2004: "Almost every commentator on the Madonna phenomenon, from fellow entertainer to cloistered academician, acknowledges her promotional genius".[227] Madonna responded to charges of cynicism/publicity stunt regarding her first adoption in 2006, and her horse-riding accident, overall saying about the issue: "If you're a celebrity, everything you do is suddenly perceived as a way to get attention".[262] Regarding criticisms towards her ever-evolving style as a tool of marketing, Madonna responded:

See alsoReferences

Book sources

Further reading |