|

Light in painting

Light in painting fulfills several objectives, both plastic and aesthetic: on the one hand, it is a fundamental factor in the technical representation of the work, since its presence determines the vision of the projected image, as it affects certain values such as color, texture and volume; on the other hand, light has a great aesthetic value, since its combination with shadow and with certain lighting and color effects can determine the composition of the work and the image that the artist wants to project. Also, light can have a symbolic component, especially in religion, where this element has often been associated with divinity. The incidence of light on the human eye produces visual impressions, so its presence is indispensable for the capture of art. At the same time, light is intrinsically found in painting, since it is indispensable for the composition of the image: the play of light and shadow is the basis of drawing and, in its interaction with color, is the primordial aspect of painting, with a direct influence on factors such as modeling and relief.[1] The technical representation of light has evolved throughout the history of painting, and various techniques have been created over time to capture it, such as shading, chiaroscuro, sfumato, or tenebrism. On the other hand, light has been a particularly determining factor in various periods and styles, such as Renaissance, Baroque, Impressionism, or Fauvism.[2] The greater emphasis given to the expression of light in painting is called "luminism", a term generally applied to various styles such as Baroque tenebrism and impressionism, as well as to various movements of the late 19th century and early 20th century such as American, Belgian, and Valencian luminism.[3]

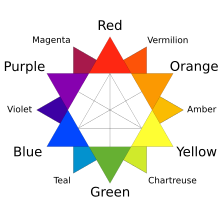

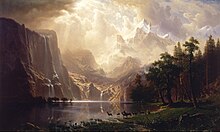

OpticsLight (ultimately from Proto-Indo-European *lewktom, with the meaning "brightess")[5] is an electromagnetic radiation with a wavelength between 380 nm and 750 nm, the part of the visible spectrum that is perceived by the human eye, located between infrared and ultraviolet radiation. It consists of massless elementary particles called photons, which move at a speed of 299 792 458 m/s in a vacuum, while in matter it depends on its refractive index . The branch of physics that studies the behavior and characteristics of light is optics.[6]  Light is the physical agent that makes objects visible to the human eye. Its origin can be in celestial bodies such as the Sun, the Moon, or the stars, natural phenomena such as lightning, or in materials in combustion, ignition, or incandescence. Throughout history, human beings have devised different procedures to obtain light in spaces lacking it, such as torches, candles, candlesticks, lamps or, more recently, electric lighting.[6] Light is both the agent that enables vision and a visible phenomenon in itself, since light is also an object perceptible by the human eye.[7] Light enables the perception of color, which reaches the retina through light rays that are transmitted by the retina to the optic nerve, which in turn transmits them to the brain by means of nerve impulses.[8] The perception of light is a psychological process and each person perceives the same physical object and the same luminosity in a different way.[9]  Physical objects have different levels of luminance (or reflectance), that is, they absorb or reflect to a greater or lesser extent the light that strikes them, which affects the color, from white (maximum reflection) to black (maximum absorption).[9] Both black and white are not considered colors of the conventional chromatic circle, but gradations of brightness and darkness, whose transitions make up the shadows.[10] When white light hits a surface of a certain color, photons of that color are reflected; if these photons subsequently hit another surface they will illuminate it with the same color, an effect known as radiance — generally perceptible only with intense light. If that object is in turn the same color, it will reinforce its level of colored luminosity, i.e. its saturation.[11] White light from the sun consists of a continuous spectrum of colors which, when divided, forms the colors of the rainbow: violet, indigo blue, blue, green, yellow, orange, and red.[12] In its interaction with the Earth's atmosphere, sunlight tends to scatter the shorter wavelengths, i.e. the blue photons, which is why the sky is perceived as blue. On the other hand, at sunset, when the atmosphere is denser, the light is less scattered, so that the longer wavelengths, red, are perceived.[13] Color is a specific wavelength of white light. The colors of the chromatic spectrum have different shades or tones, which are usually represented in the chromatic circle, where the primary colors and their derivatives are located. There are three primary colors: lemon yellow, magenta red, and cyan blue. If they are mixed, the three secondary colors are obtained: orange red, bluish violet, and green. If a primary and a secondary are mixed, the tertiary colors are obtained: greenish blue, orange yellow, etc. On the other hand, complementary colors are two colors that are on opposite sides of the chromatic circle (green and magenta, yellow and violet, blue and orange) and adjacent colors are those that are close within the circle (yellow and green, red and orange). If a color is mixed with an adjacent color, it is shaded, and if it is mixed with a complementary color, it is neutralized (darkened). Three factors are involved in the definition of color: hue, the position within the chromatic circle; saturation, the purity of the color, which is involved in its brightness – the maximum saturation is that of a color that has no mixture with black or its complementary; and value, the level of luminosity of a color, increasing when mixed with white and decreasing when mixed with black or a complementary.[14]  The main source of light is the Sun and its perception can vary according to the time of day: the most normal is mid-morning or mid-afternoon light, generally blue, clear and diaphanous, although it depends on atmospheric dispersion and cloudiness and other climatic factors; midday light is whiter and more intense, with high contrast and darker shadows; dusk light is more yellowish, soft and warm; sunset light is orange or red, low contrast, with intense bluish shadows; evening light is a darker red, dimmer light, with weaker shadows and contrast (the moment known as alpenglow, which occurs in the eastern sky on clear days, gives pinkish tones); the light of cloudy skies depends on the time of day and the degree of cloudiness, is a dim and diffuse light with soft shadows, low contrast and high saturation (in natural environments there can be a mixture of light and shadow known as "mottled light"); finally, night light can be lunar or some atmospheric refraction of sunlight, is diffuse and dim (in contemporary times there is also light pollution from cities).[15] We must also point out the natural light that filters indoors, a diffuse light of lower intensity, with a variable contrast depending on whether it has a single origin or several (for example, several windows), as well as a coloring also variable, depending on the time of day, the weather or the surface on which it is reflected. An outstanding interior light is the so-called "north light", which is the light that enters through a north-facing window, which does not come directly from the sun -always located to the south- and is therefore a soft and diffuse, constant and homogeneous light, much appreciated by artists in times when there was no adequate artificial lighting.[16]  As for artificial light, the main ones are: fire and candles, red or orange; electric, yellow or orange – generally tungsten or wolfram – it can be direct (focal) or diffused by lamp shades; fluorescent, greenish; and photographic, white (flash light). Logically, in many environments there can be mixed light, a combination of natural and artificial light.[17] The visible reality is made up of a play of light and shadow: the shadow is formed when an opaque body obstructs the path of the light. In general, there is a ratio between light and shadow whose gradation depends on various factors, from lighting to the presence and placement of various objects that can generate shadows; however, there are conditions in which one of the two factors can reach the extreme, as in the case of snow or fog or, conversely, at night. We speak of high key lighting when white or light tones predominate, or low key lighting if black or dark tones predominate.[18] Shadows can be of shape (also called "self shadows") or of projection ("cast shadows"): the former are the shaded areas of a physical object, that is, the part of that object on which light does not fall; the latter are the shadows cast by these objects on some surface, usually the ground.[19] Self shadows define the volume and texture of an object; cast shadows help define space.[20] The lightest part of the shadow is the "umbra" and the darkest part is the "penumbra". The shape and appearance of the shadow depends on the size and distance of the light source: the most pronounced shadows are from small or distant sources, while a large or close source will give more diffuse shadows. In the first case, the shadow will have sharp edges and the darker area (penumbra) will occupy most of it; in the second, the edge will be more diffuse and the umbra will predominate. A shadow can receive illumination from a secondary source, known as "fill light". The color of a shadow is between blue and black, and also depends on several factors, such as light contrast, transparency and translucency.[17] The projection of shadows is different if they come from natural or artificial light: with natural light the beams are parallel and the shadow adapts both to the terrain and to the various obstacles that may intervene; with artificial light the beams are divergent, with less defined limits, and if there are several light sources, combined shadows may be produced.[21] The reflection of light produces four derived phenomena: glints, which are reflections of the light source, be it the Sun, artificial lights or incidental sources such as doors and windows; glares, which are reflections produced by illuminated bodies as a reflective screen, especially white surfaces; color reflections, produced by the proximity between various objects, especially if they are luminous; and image reflections, produced by polished surfaces, such as mirrors or water. Another phenomenon produced by light is transparency, which occurs in bodies that are not opaque, with a greater or lesser degree depending on the opacity of the object, from total transparency to varying degrees of translucency. Transparency generates filtered light, a type of luminosity that can also be produced through curtains, blinds, awnings, various fabrics, pergolas and arbors, or through the foliage of trees.[22] Pictorial representation of light

In artistic terminology, "light" is the point or center of light diffusion in the composition of a painting, or the luminous part of a painting in relation to the shadows. This term is also used to describe the way a painting is illuminated: zenithal or plumb light (vertical rays), high light (oblique rays), straight light (horizontal rays), workshop or studio light (artificial light), etc.[24] The term "accidental light" is also used to refer to light not produced by the Sun, which can be either moonlight or artificial light from candles, torches, etc.[25] The light can come from different directions, which according to its incidence can be differentiated between: "lateral", when it comes from the side, it is a light that highlights more the texture of the objects; "frontal", when it comes from the front, it eliminates the shadows and the sensation of volume; "zenithal", a vertical light of higher origin than the object, it produces a certain deformation of the figure; "contrapicado", vertical light of lower origin, it deforms the figure in an exaggerated way; and "backlight", when the origin is behind the object, thus darkening and diluting its silhouette.[20] In relation to the distribution of light in the painting, it can be: "homogeneous", when it is distributed equally; "dual", in which the figures stand out against a dark background; or "insertive", when light and shadows are interrelated.[26] According to its origin, light can be intrinsic ("own or autonomous light"), when the light is homogeneous, without luminous effects, directional lights or contrasts of lights and shadows; or extrinsic ("illuminating light"), when it presents contrasts, directional lights and other objective sources of light. The first occurred mainly in Romanesque and Gothic art, and the second especially in the Renaissance and Baroque.[27] In turn, the illuminating light can occur in different ways: "focal light", when it directly presents a light-emitting object ("tangible light") or comes from an external source that illuminates the painting ("intangible light"); "diffuse light", which blurs the contours, as in Leonardo's sfumato; "real light", which aims to realistically capture sunlight, an almost utopian attempt in which artists such as Claude of Lorraine, J. M. W. Turner or the impressionist artists were especially employed; and "unreal light", which has no natural or scientific basis and is closer to a symbolic light, as in the illumination of religious figures.[28] As for the artist's intention, light can be "compositional", when it helps the composition of the painting, as in all the previous cases; or "conceptual light", when it serves to enhance the message, for example by illuminating a certain part of the painting and leaving the rest in semi-darkness, as Caravaggio used to do.[29] In terms of its origin, light can be "natural ambient light", in which no shadows of figures or objects appear, or "projected light", which generates shadows and serves to model the figures.[27] It is also important to differentiate between source and focus of light: the source of light in a painting is the element that radiates the light, be it the sun, a candle or any other; the focus of light is the part of the painting that has the most luminosity and radiates it around the painting.[20] On the other hand, in relation to the shadow, the interrelation between light and shadow is called "chiaroscuro"; if the dark area is larger than the illuminated one, it is called "tenebrism".[29]  Light in painting plays a decisive role in the composition and structuring of the painting. Unlike in architecture and sculpture, where light is real, the light of the surrounding space, in painting light is represented, so it responds to the will of the artist both in its physical and aesthetic aspect. The painter determines the illumination of the painting, that is to say, the origin and incidence of the light, which marks the composition and expression of the image.[30] In turn, the shadow provides solidity and volume, while it can generate dramatic effects of various kinds.[19] In the pictorial representation of light it is essential to distinguish its nature (natural, artificial) and to establish its origin, intensity and chromatic quality. Natural light depends on various factors, such as the season of the year, the time of day (auroral, diurnal, twilight or nocturnal light – from the Moon or stars) or the weather. Artificial light, on the other hand, differs according to its origin: a candle, a torch, a fluorescent, a lamp, neon lights, etc. As for the origin, it can be focused or act in a diffuse way, without a determined origin. The chromatism of the image depends on the light, since depending on its incidence an object can have different tonalities, as well as the reflections, ambiances and shadows projected.[31] In an illuminated image the color is considered saturated at the correct level of illumination, while the color in shadow will always have a darker tonal value and will be the one that determines the relief and volume.[32] Light is linked to space, so in painting it is intimately linked to perspective, the way of representing a three-dimensional space in a two-dimensional support such as painting. Thus, in linear perspective, light fulfills the function of highlighting objects, of generating volume, through modeling, in the form of luminous gradations; while in aerial perspective, the effects of light are sought as they are perceived by the spectator in the environment, as another element present in the physical reality represented. The light source can be present in the painting or not, it can have a direct or indirect origin, internal or external to the painting.[30] The light defines the space through the modeling of volumes, which is achieved with the contrast between light and shadow: the relationship between the values of light and shadow defines the volumetric characteristics of the form, with a scale of values that can range from a soft fade to a hard contrast.[33] Spatial limits can be objective, when they are produced by people, objects, architectures, natural elements and other factors of corporeality; or subjective, when they come from sensations such as atmosphere, depth, a hollow, an abyss, etc. In human perception, light creates closeness and darkness creates remoteness, so that a light-darkness gradient gives a sensation of depth.[34]  Aspects such as contrast, relief, texture, volume, gradients or the tactile quality of the image depend on light. The play of light and shadow helps to define the location and orientation of objects in space. For their correct representation, their shape, density and extension, as well as their differences in intensity, must be taken into account. It should also be taken into account that, apart from its physical qualities, light can generate dramatic effects and give the painting a certain emotional atmosphere.[35] Contrast is a fundamental factor in painting; it is the language with which the image is shaped. There are two types of contrast: the "luminous", which can be by chiaroscuro (light and shadow) or by surface (a point of light that shines brighter than the rest); and the "chromatic", which can be tonal (contrast between two tones) or by saturation (a bright color with a neutral one). Both types of contrast are not mutually exclusive, in fact they coincide in the same image most of the time. Contrast can have different levels of intensity and its regulation is the artist's main tool to achieve the appropriate expression for his work.[36] From the contrast between light and shadow depends the tonal expression that the artist wants to give to his work, which can range from softness to hardness, which gives a lesser or greater degree of dramatization. Backlighting, for example, is one of the resources that provide greater drama, since it produces elongated shadows and darker tones.[31]  The correspondence between light and shadow and color is achieved through tonal evaluation: the lightest tones are found in the most illuminated areas of the painting and the darkest in those that receive less illumination. Once the artist establishes the tonal values, he chooses the most appropriate color ranges for their representation. Colors can be lightened or darkened until the desired effect is achieved: to lighten a color, lighter related colors – such as groups of warm or cool colors – are added to it, as well as amounts of white until the right tone is found; to darken, related dark colors and some blue or shadow are added. In general, the shade is made by mixing a color with a darker shade, plus blue and a complementary of the proper color (such as yellow and dark blue, red and primary blue or magenta and green).[37] The light and chromatic harmony of a painting depends on color, i.e. the relationship between the parts of a painting to create cohesion. There are several ways to harmonize: it can be done through "monochrome and tone dominant melodic ranges", with a single color as a base to which the value and tone is changed; if the value is changed with white or black it is a monochrome, while if the tone is changed it is a simple melodic range: for example, taking red as the dominant tone can be shaded with various shades of red (vermilion, cadmium, carmine) or orange, pink, violet, maroon, salmon, warm gray, etc. Another method is the "harmonic trios", which consists of combining three colors equidistant from each other on the chromatic circle; there can also be four, in which case we speak of "quaternions". Another way is the combination of "warm and cool thermal ranges": warm colors are for example red, orange, purple and yellowish green, as well as black; cool colors are blue, green and violet, as well as white (this perception of color with respect to its temperature is subjective and comes from Goethe's Theory of Colors). It is also possible to harmonize between "complementary colors", which is the one that produces the greatest chromatic contrast. Finally, "broken ranges" consist of neutralization by mixing primary colors and their complementary colors, which produces intense luminous effects, since the chromatic vibration is more subtle and the saturated colors stand out more.[38] Techniques The quality and appearance of the luminous representation is in many cases linked to the technique used. The expression and the different light effects of a work depend to a great extent on the different techniques and materials used. In drawing, whether in pencil or charcoal, the effects of light are achieved through the black-white duality, where white is generally the color of the paper (there are colored pencils, but they produce little contrast, so they are not very suitable for chiaroscuro and light effects). Pencil is usually worked with line and hatching, or by means of blurred spots. Charcoal allows the use of gouache and chalk or white chalk to add touches of light, as well as sanguine or sepia.[39] Another monochrome technique is Indian ink, which generates very violent chiaroscuro, without intermediate values, making it a very expressive medium.[40] Oil painting consists of dissolving the colors in an oily binder (linseed, walnut, almond or hazelnut oil; animal oils), adding turpentine to make it dry better.[41] The oil painting is the one that best allows to value the light effects and the chromatic tones.[42] It is a technique that produces vivid colors and intense effects of brightness and brilliance, and allows a free and fresh stroke, as well as a great richness of textures. On the other hand, thanks to its long permanence in a fluid state, it allows for subsequent corrections.  For its application, brushes, spatulas or scrapers can be used, allowing multiple textures, from thin layers and glazes to thick fillings, which produce a denser light.[40] Pastel painting is made with a pigment pencil of various mineral colors, with binders (kaolin, gypsum, gum arabic, fig latex, fish glue, candi sugar, etc.), kneaded with wax and Marseilles soap and cut into sticks. The color should be spread with a smudger, a cylinder of leather or paper used to smudge the color strokes.[41] Pastel combines the qualities of drawing and painting, and brings freshness and spontaneity.[43] Watercolor is a technique made with transparent pigments diluted in water, with binders such as gum arabic or honey, using the white of the paper itself. Known since ancient Egypt, it has been a technique used throughout the ages, although with more intensity during the 18th and 19th centuries.[41] As it is a wet technique, it provides great transparency, which highlights the luminous effect of the white color. Generally, the light tones are applied first, leaving spaces on the paper for the pure white; then the dark tones are applied.[44] In acrylic paint, a plastic binder is added to the colorant, which produces a fast drying and is more resistant to corrosive agents. The speed of drying allows the addition of multiple layers to correct defects and produces flat colors and glazes. Acrylic can be worked by gradient, blurred or contrasted, by flat spots or by filling the color, as in the oil technique.[44] Genres Depending on the pictorial genre, light has different considerations, since its incidence is different in interiors than in exteriors, on objects than on people. In interiors, light generally tends to create intimate environments, usually a type of indirect light filtered through doors or windows, or filtered by curtains or other elements. In these spaces, private scenes are usually developed, which are reinforced by contrasts of light and shadow, intense or soft, natural or artificial, with areas in semi-darkness and atmospheres influenced by gravitating dust and other effects caused by these spaces. A separate genre of interior painting is naturaleza muerta or "still life", which usually shows a series of objects or food arranged as in a sideboard. In these works the artist can manipulate the light at will, generally with dramatic effects such as side lights, frontal lights, zenithal lights, back lights, back-lights, etc. The main difficulty consists in the correct evaluation of the tones and textures of the objects, as well as their brightness and transparency depending on the material.[45] In exteriors, the main genre is landscape, perhaps the most relevant in relation to light in that its presence is fundamental, since any exterior is enveloped in a luminous atmosphere determined by the time of day and the weather and environmental conditions. There are three main types of landscapes: landscape, seascape, and skyscape. The main challenge for the artist in these works is to capture the precise tone of the natural light according to the time of day, the season of the year, the viewing conditions – which can be affected by phenomena such as cloud cover, rain or fog – and an infinite number of variables that can occur in a medium as volatile as the landscape. On numerous occasions artists have gone out to paint in nature to capture their impressions first hand, a working method known by the French term en plen air ("in the open air", equivalent to "outdoors"). There is also the variant of the urban landscape, frequent especially since the 20th century, in which a factor to take into account is the artificial illumination of the cities and the presence of neon lights and other types of effects; in general, in these images the planes and contrasts are more differentiated, with hard shadows and artificial and grayish colors.[46]  Light is also fundamental for the representation of the human figure in painting, since it affects the volume and generates different limits according to the play of light and shadow, which delimits the anatomical profile. Light allows us to nuance the surface of the body, and provides a sensation of smoothness and softness to the skin. The focus of the light is important, since its direction influences the general contour of the figure and the illumination of its surroundings: for example, frontal light makes the shadows disappear, attenuating the volume and the sensation of depth, while emphasizing the color of the skin. On the other hand, a partially lateral illumination causes shadows and gives relief to the volumes, and if it is from the side, the shadow covers the opposite side of the figure, which appears with an enhanced volume. On the other hand, in backlighting the body is shown with a characteristic halo around its contour, while the volume acquires a weightless sensation. With overhead lighting, the projection of shadows blurs the relief and gives a somewhat ghostly appearance, just as it does when illuminated from below – although the latter is rare. A determining factor is that of the shadows, which generate a series of contours apart from the anatomical ones that provide drama to the image. Together with the luminous reflections, the gradation of shadows generates a series of effects of great richness in the figure, which the artist can exploit in different ways to achieve different results of greater or lesser effect. It should also be taken into account that direct light or shadow on the skin modifies the color, varying the tonality from the characteristic pale pink to gray or white. The light can also be filtered by objects that get in its path (such as curtains, fabrics, vases or various objects), which generates different effects and colors on the skin.[47] In relation to the human being, the portrait genre is characteristic, in which light plays a decisive role in the modeling of the face. Its elaboration is based on the same premises as those of the human body, with the addition of a greater demand in the faithful representation of the physiognomic features and even the need to capture the psychology of the character. The drawing is essential to model the features according to the model and, from there, light and color are again the vehicle of translation of the visual image to its representation on the canvas.[48] In the 20th century, abstraction emerged as a new pictorial language, in which painting is reduced to non-figurative images that no longer describe reality, but rather concepts or sensations of the artist himself, who plays with form, color, light, matter, space and other elements in a totally subjective way and not subject to conventionalisms. Despite the absence of concrete images of the surrounding reality, light is still present on numerous occasions, generally contributing luminosity to the colors or creating chiaroscuro effects by contrasting tonal values.[49] Chronological factor Another aspect in which light is a determining factor is in time, in the representation of chronological time in painting. Until the Renaissance, artists did not represent a specific time in painting and, in general, the only difference in light was between exterior and interior lights. In many occasions it is difficult to identify the specific time of day in a work, since neither the direction of the light nor its quality nor the dimension of the shadows are decisive elements to recognize a certain time of day. Night was rarely represented until practically Mannerism and, in the cases in which a nocturnal atmosphere was used, it was because the narrative required it or because of some symbolic aspect: in Giotto's The Annunciation to the Shepherds or in Ambrogio Lorenzetti's Annunciation, the nocturnal atmosphere contributes to accentuate the halo of mystery surrounding the birth of Christ; in Uccello's Saint George and the Dragon, night represents evil, the world in which the dragon lives. On the other hand, even in narrative themes that take place at night, such as the Last Supper or the supper at Emmaus, this factor is sometimes deliberately avoided, as in Andrea del Sarto's Last Supper, set in daylight.[50] Generally, the chronological setting of a scene has been linked to its narrative correlate, albeit in an approximate manner and with certain licenses on the part of the artist. Practically until the 19th century, it was not until the industrial civilization, thanks to the advances in artificial lighting, that a complete and exact use of the entire time zone was achieved, thanks to the advances in artificial illumination. But just as in the contemporary age time has had a more realistic component, in the past it was more of a narrative factor, accompanying the action represented: dawn was a time of travel or hunting; noon, of action or its subsequent rest; dusk, of return or reflection; night was sleep, fear or adventure, or fun and passion; birth was morning, death was night.[51]  The temporal dimension began to gain relevance in the 17th century, when artists such as Claude Lorrain and Salvator Rosa began to detach landscape painting from a narrative context and to produce works in which the protagonist was nature, with the only variations being the time of day or the season of the year. This new conception developed with 18th-century Vedutism and 19th-century Romantic landscape, and culminated with Impressionism.[52] The first light of the day is that of dawn, sunrise or aurora (sometimes the aurora, which would be the first brightness of the sky, is differentiated from dawn, which would correspond to sunrise). Until the 17th century, dawn appeared only in small pieces of landscape, usually behind a door or a window, but was never used to illuminate the foreground. The light of dawn generally has a spherical effect, so until the appearance of Leonardo's aerial perspective it was not widely used. In his Dictionary of the Fine Arts of Design (1797), Francesco Milizia states that:

For Milizia, the light of dawn was the most suitable for the representation of landscapes.[53] Noon and the hours immediately before and after have always been a stable frame for an objective representation of reality, although it is difficult to pinpoint the exact moment in most paintings depending on the different light intensities. On the other hand, the exact noon was discouraged by its extreme refulgence, to the point that Leonardo advised that:

Milizia also points out that:

Most art treatises advised the afternoon light, which was the most used especially from the Renaissance to the 18th century. Vasari advised to place the sun to the east because "the figure that is made has a great relief and great goodness and perfection is achieved".[54] In the early days of modern painting, the sunset used to be circumscribed to a celestial vault characterized by its reddish color, without an exact correspondence with the illumination of figures and objects. It was again with Leonardo that a more naturalistic study of twilight began, pointing out in his notes that:

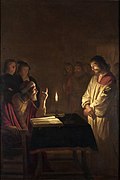

For Milizia this moment is risky, since "the more splendid these accidents are (the flaming twilight is always an excess), the more they must be observed to represent them well".[55] Finally, the night has always been a singularity within painting, to the point of constituting a genre of its own: the nocturne. In these scenes the light comes from the Moon, the stars or from some type of artificial illumination (bonfires, torches, candles or, more recently, gas or electric light). The justification for a night scene has generally been given from iconographic themes occurring in this time period. In the 14th century painting began to move away from the symbolic and conceptual content of medieval art in search of a figurative content based on a more objective spatio-temporal axis. Renaissance artists were refractory to the nocturnal setting, since their experimentation in the field of linear perspective required an objective and stable frame in which full light was indispensable. Thus, Lorenzo Ghiberti stated that "it is not possible to be seen in darkness" and Leonardo wrote that "darkness means complete deprivation of light". Leonardo advised a night scene only with the illumination of a fire, as a mere artifice to make a night scene diurnal. However, Leonardo's sfumato opened a first door to a naturalistic representation of the night, thanks to the chromatic decrease in the distance in which the bluish white of Leonardo's luminous air can become a bluish black for the night: just as the first creates an effect of remoteness, the second provokes closeness, the dilution of the background in the gloom. This tendency will have its climax in baroque tenebrism, in which darkness is used to add drama to the scene and to emphasize certain parts of the painting, often with a symbolic aspect. On the other hand, in the 17th century the representation of the night acquired a more scientific character, especially thanks to the invention of the telescope by Galileo and a more detailed observation of the night sky. Finally, advances in artificial lighting in the 19th century boosted the conquest of nighttime, which became a time for leisure and entertainment, a circumstance that was especially captured by the Impressionists.[56]

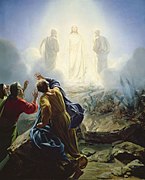

Symbology Light has had on numerous occasions throughout the history of painting an aesthetic component, which identifies light with beauty, as well as a symbolic meaning, especially related to religion, but also with knowledge, good, happiness and life,[59] or in general the spiritual and immaterial.[60] Sometimes the light of the Sun has been equated with inspiration and imagination, and that of the Moon with rational thought.[60] In contrast, shadows and darkness represent evil, death, ignorance, immorality, misfortune or secrecy.[60] Thus, many religions and philosophies throughout history have been based on the dichotomy between light and darkness, such as Ahura Mazda and Ahriman, yin and yang, angels and demons, spirit and matter, and so on.[60] In general, light has been associated with the immaterial and spiritual, probably because of its ethereal and weightless aspect, and that association has often been extended to other concepts related to light, such as color, shadow, radiance, evanescence, etc.[23] The identification of light with a transcendent meaning comes from antiquity and probably existed in the minds of many artists and religious people before the idea was written down. In many ancient religions the deity was identified with light, such as the Semitic Baal, the Egyptian Ra or the Iranian Ahura Mazda. Primitive peoples already had a transcendental concept of light – the so-called "metaphor of light" – generally linked to immortality, which related the afterlife to starlight. Many cultures sketched a place of infinite light where the souls rested, a concept also picked up by Aristotle and various Fathers of the Church such as Saint Basil and Saint Augustine. On the other hand, many religious rites were based on "illumination" to purify the soul, from ancient Babylon to the Pythagoreans.[61] In Greek mythology Apollo was the god of the Sun and has often been depicted in art within a disk of light.[62] On the other hand, Apollo was also the god of beauty and the arts, a clear symbolism between light and these two concepts.[20] Also related to light is the goddess of dawn, Eos (Aurora in Roman mythology).[63] In Ancient Greece, light was synonymous with life and was also related to beauty. Sometimes the fluctuation of light was related to emotional changes, as well as to intellectual capacity. On the other hand, the shadow had a negative component, it was related to the dark and hidden, to evil forces, such as the spectral shadows of Tartarus.[64] The Greeks also related the sun to "intelligent light" (φῶς νοετόν), a driving principle of the movement of the universe, and Plato drew a parallel between light and knowledge.[61] The ancient Romans distinguished between lux (luminous source) and lumen (rays of light emanating from that source), terms they used according to the context: thus, for example, lux gloriae or lux intelligibilis, or lumen naturale or lumen gratiae.[61] In Christianity, God is also often associated with light, a tradition that goes back to the philosopher Pseudo-Dionysius Areopagite (On the Celestial Hierarchy, On the Divine Names), who adapted a similar one from Neoplatonism. For this 5th century author, "Light derives from Good and is the image of Goodness". Later, in the 9th century, John Scotus Erigena defined God as "the father of lights".[65] Already the Bible begins with the phrase "let there be light" (Ge 1:3) and points out that "God saw that the light was good" (Ge 1:4). This "good" had in Hebrew a more ethical sense, but in its translation into Greek the term καλός (kalós, "beautiful") was used, in the sense of kalokagathía, which identified goodness and beauty; although later in the Latin Vulgate a more literal translation was made (bonum instead of pulchrum), it remained fixed in the Christian mentality the idea of the intrinsic beauty of the world as the work of the Creator. On the other hand, the Holy Scriptures identify light with God, and Jesus goes so far as to affirm: "I am the light of the world, he who follows me will not walk in darkness, for he will have the light of life" (John 8:12).[66] This identification of light with divinity led to the incorporation in Christian churches of a lamp known as "eternal light", as well as the custom of lighting candles to remember the dead and various other rites.[67]  Light is also present in other areas of the Christian religion: the Conception of Jesus in Mary is realized in the form of a ray of light, as seen in numerous representations of the Annunciation;[59] likewise, it represents the Incarnation, as expressed by Pseudo-Saint Bernard: "as the splendor of the sun passes through glass without breaking it and penetrates its solidity in its impalpable subtlety, without opening it when it enters and without breaking it when it leaves, so the Word God penetrates Mary's womb and comes forth from her womb intact."[68] This symbolism of light passing through glass is the same concept that was applied to Gothic stained glass, where light symbolizes divine omnipresence.[68] Another symbolism related to light is that which identifies Jesus with the Sun and Mary as the Dawn that precedes him.[63] In addition to all this, in Christianity light can also signify truth, virtue and salvation. In patristics, light is a symbol of eternity and the heavenly world: according to Saint Bernard, souls separated from the body will be "plunged into an immense ocean of eternal light and luminous eternity". On the other hand, in ancient Christianity, baptism was initially called "illumination".[69] In Orthodox Christianity, light is, more than a symbol, a "real aspect of divinity," according to Vladimir Lossky. A reality that can be apprehended by the human being, as expressed by Saint Simeon the New Theologian:

Because of the opposition of light and darkness, this element has also been used on occasions as a repeller of demons, so that light has often been represented in various acts and ceremonies such as circumcision, baptisms, weddings or funerals, in the form of candles or fires.[59][68]  In Christian iconography, light is also present in the halos of the saints, which used to be made – especially in medieval art – with a golden nimbus, a circle of light placed around the heads of saints, angels and members of the Holy Family. In Fra Angelico's The Annunciation, in addition to the halo, the artist placed rays of light radiating from the figure of the archangel Gabriel, to emphasize his divinity, the same resource he uses with the dove symbolizing the Holy Spirit.[70] On other occasions, it is God himself who is represented in the form of rays of sunlight, as in The Baptism of Christ (1445) by Piero della Francesca.[71] The rays can also signify God's wrath, as in The Tempest (1505) by Giorgione. On other occasions light represents eternity or divinity: in the vanitas genre, beams of light used to focus on objects whose transience was to be emphasized as a symbol of the ephemerality of life, as in Vanities (1645) by Harmen Steenwijck, where a powerful beam of light illuminates the skull in the center of the painting.[72] Between the 14th and 15th centuries Italian painters used supernatural-looking lights in night scenes to depict miracles: for example, in the Annunciation to the Shepherds by Taddeo Gaddi (Santa Croce, Florence) or in the Stigmatization of Saint Francis by Gentile da Fabriano (1420, private collection). In the 16th century, supernatural lights with brilliant effects were also used to point out miraculous events, as in Matthias Grünewald's Risen Christ (1512-1516, Isenheim altar, Museum Unterlinden, Colmar) or in Titian's Annunciation (1564, San Salvatore, Venice). In the following century, Rembrandt and Caravaggio identified light in their works with divine grace and as an agent of action against evil.[73] The Baroque was the period in which light became more symbolic: in medieval art the luminosity of the backgrounds, of the halos of the saints and other objects – generally made with gold leaf – was an attribute that did not correspond to real luminosity, while in the Renaissance it responded more to a desire for experimentation and aesthetic delight; Rembrandt was the first to combine both concepts, the divine light is a real, sensory light, but with a strong symbolic charge, an instrument of revelation.[9]  Between the 17th and 18th centuries, mystical theories of light were abandoned as philosophical rationalism gained ground. From transcendental or divine light, a new symbolism of light evolved that identified it with concepts such as knowledge, goodness or rebirth, and opposed it to ignorance, evil and death.[74] Descartes spoke of an "inner light" capable of capturing the "eternal truths", a concept also taken up by Leibniz, who distinguished between lumière naturelle (natural light) and lumière révélée (revealed light).[75] In the 19th century light was related by the German Romantics (Friedrich Schlegel, Friedrich Schelling, Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel) to nature, in a pantheistic sense of communion with nature. For Schelling, light was a medium in which the "universal soul" (Weltseele) moved. For Hegel, light was the "ideality of matter", the foundation of the material world.[75] Between the 19th and 20th centuries, a more scientific view of light prevailed. Science had been trying to unravel the nature of light since the early Modern Age, with two main theories: the corpuscular theory, defended by Descartes and Newton; and the wave theory, defended by Christiaan Huygens, Thomas Young and Augustin-Jean Fresnel. Later, James Clerk Maxwell presented an electromagnetic theory of light. Finally, Albert Einstein brought together the corpuscular and wave theories.[76] Light can also have a symbolic character in landscape painting: in general, dawn and the passage from night to day represent the divine plan – or cosmic system – that transcends the simple will of the human being; dawn also symbolizes the renewal and redemption of Christ. On other occasions, the sun and the moon have been associated with various vital forces: thus, the sun and the day are associated with the masculine, the vital force and energy; and the moon and the night with the feminine, rest, sleep and spirituality, sometimes even death.[77] In other religions light also has a transcendent meaning: in Buddhism it represents truth and the overcoming of matter in the ascent to nirvana. In Hinduism it is synonymous with wisdom and the spiritual understanding of participation with divinity (atman); it is also the manifestation of Krishna, the "Lord of Light".[67] In Islam it is the sacred name Nûr. According to the Koran (24:35), "Allah is the light of the heavens and the earth. Light upon light! Allah guides to his light whomever he wills". In the Zohar of the Jewish Kabbalah the primordial light Or (or Awr) appears, and points out that the universe is divided between the empires of light and darkness; also in Jewish synagogues there is usually a lamp of "eternal light" or ner tamid. Finally, in Freemasonry, the search for light is considered the ascent to the various Masonic degrees; some of the Masonic symbols, such as the compass, the bevel and the holy book, are called "great lights"; also the principal Masonic officials are called "lights". On the other hand, initiation into Freemasonry is called "receiving the light".

History

The use of light is intrinsic to painting, so it has been present directly or indirectly since prehistoric times, when cave paintings sought light and relief effects by taking advantage of the roughness of the walls where these scenes were represented. However, serious attempts at greater experimentation in the technical representation of light did not take place until classical Greco-Roman art: Francisco Pacheco, in El arte de la pintura (1649), points out that: "adumbration was invented by Surias, Samian, covering or staining the shadow of a horse, looked at in the sunlight". On the other hand, Apollodorus of Athens is credited with the invention of chiaroscuro, a procedure of contrast between light and shadow to produce effects of luminous reality in a two-dimensional representation such as painting. The effects of light and shadow were also developed by Greek scenographers in a technique called skiagraphia, consisting of the contrast between black and white to create contrast, to the point that they were called "shadow painters".[79] The first scientific studies on light also emerged in Greece: Aristotle stated in relation to colors that they are "mixtures of different forces of sunlight and the light of fire, air and water", as well as that "darkness is due to the deprivation of light". One of the most famous Greek painters was Apelles, one of the pioneers in the representation of light in painting. Pliny said of Apelles that he was the only one who "painted what cannot be painted, thunder, lightning and thunderbolts". Another outstanding painter was Nicias of Athens, of whom Pliny praised the "care he took with light and shade to achieve the appearance of relief".[80] With the emergence of landscape painting, a new method was developed to represent distance through gradations of light and shadow, contrasting more the plane closest to the viewer and progressively blurring with distance. These early landscape painters created the modeling through shades of light and shadow, without mixing the colors in the palette. Claudius Ptolemy explained in his Optics how painters created the illusion of depth through distances that seemed "veiled by air". In general, the strongest contrasts were made in the areas closest to the observer and progressively reduced towards the background. This technique was picked up by early Christian and Byzantine art, as seen in the apsidal mosaic of Sant'Apollinare in Classe, and even reached as far as India, as denoted in the Buddhist murals of Ajantā.[81] In the 5th century the philosopher John Philoponus, in his commentary on Aristotle's Meteorology, outlined a theory on the subjective effect of light and shadow in painting, known today as "Philoponus' rule":

This effect was already known empirically by ancient painters. Cicero was of the opinion that painters saw more than normal people in umbris et eminentia ("in shadows and eminences"), that is, depth and protrusion. And Pseudo-Longinus – in his work On the Sublime – said that "although the colors of shadow and light are on the same plane, side by side, the light jumps immediately into view and seems not only to stand out but actually to be closer."[83] Hellenistic art was fond of light effects, especially in landscape painting, as denoted in the stuccoes of La Farnesina. Chiaroscuro was widely used in Roman painting, as denoted in the illusory architectures of the frescoes of Pompeii, although it disappeared during the Middle Ages.[84] Vitruvius recommended as more suitable for painting the northern light, being more constant due to its low mutability in tone. Later, in Paleochristian art, the taste for contrasts between light and shadow became evident – as can be seen in Christian sepulchral paintings and in the mosaics of Santa Pudenciana and Santa María la Mayor – in such a way that this style has sometimes been called "ancient impressionism".[85] Byzantine art inherited the use of illusionistic touches of light that were used in Pompeian art, but just as in the original its main function was naturalistic, here it is already a rhetorical formula far removed from the representation of reality. In Byzantine art, as well as in Romanesque art, which it powerfully influenced, the luminosity and splendor of shines and reflections, especially of gold and precious stones, were more valued, with a more aesthetic than pictorial component, since these shines were synonymous of beauty, of a type of beauty more spiritual than material. These briils were identified with the divine light, as did Abbot Suger to justify his expenditure on jewels and precious materials.[86] Both Greek and Roman art laid the foundations of the style known as classicism, whose main premises are truthfulness, proportion and harmony. Classicist painting is fundamentally based on drawing as a preliminary design tool, on which the pigment is applied taking into account a correct proportion of chromaticism and shading. These precepts laid the foundations of a way of understanding art that has lasted throughout history, with a series of cyclical ups and downs that have been followed to a greater or lesser extent: some of the periods in which the classical canons have been returned to were the Renaissance, Baroque classicism, neoclassicism and academicism.[87] Medieval art The art historian Wolfgang Schöne divided the history of painting in terms of light into two periods: "proper light" (eigenlicht), which would correspond to medieval art; and "illuminating light" (beleuchtungslicht), which would develop in modern and contemporary art (Über das Licht in der Malerei, Berlin, 1979).[88] In the Middle Ages, light had a strong symbolic component in art, since it was considered a reflection of divinity. Within medieval scholastic philosophy, a current called the aesthetics of light emerged, which identified light with divine beauty, and greatly influenced medieval art, especially Gothic art: the new Gothic cathedrals were brighter, with large windows that flooded the interior space, which was indefinite, without limits, as a concretion of an absolute, infinite beauty. The introduction of new architectural elements such as the pointed arch and the ribbed vault, together with the use of buttresses and flying buttresses to support the weight of the building, allowed the opening of windows covered with stained glass that filled the interior with light, which gained in transparency and luminosity.[89] These stained-glass windows allowed the light that entered through them to be nuanced, creating fantastic plays of light and color, fluctuating at different times of the day, which were reflected in a harmonious way in the interior of the buildings. Light was associated with divinity, but also with beauty and perfection: according to Saint Bonaventure (De Intelligentii), the perfection of a body depends on its luminosity ("perfectio omnium eorum quae sunt in ordine universo, est lux"). William of Auxerre (Summa Aurea) also related beauty and light, so that a body is more or less beautiful according to its degree of radiance.[90] This new aesthetics was parallel in many moments to the advances of science in subjects such as optics and the physics of light, especially thanks to the studies of Roger Bacon. At this time the works of Alhacen were also known, which would be collected by Witelo in De perspectiva (ca. 1270–1278) and Adam Pulchrae Mulieris in Liber intelligentiis (ca. 1230).[91]  The new prominence given to light in medieval times had a powerful influence on all artistic genres, to the point that Daniel Boorstein points out that "it was the power of light that produced the most modern artistic forms, because light, the almost instantaneous messenger of sensation, is the swiftest and most transitory element". In addition to architecture, light had a special influence on the miniature, with manuscripts illuminated with bright and brilliant colors, generally thanks to the use of pure colors (white, red, blue, green, gold and silver), which gave the image a great luminosity, without shades or chiaroscuro. The conjugation of these elementary colors generates light by the overall concordance, thanks to the approximation of the inks, without having to resort to shading effects to outline the contours. The light radiates from the objects, which are luminous without the need for the play of volumes that will be characteristic of modern painting. In particular, the use of gold in medieval miniatures generated areas of great light intensity, often contrasted with cold and light tones, to provide greater chromaticism.[92] However, in painting, light did not have the prominence it had in architecture: medieval "proper light" was alien to reality and without contact with the spectator, since it neither came from outside – lacking a light source – nor went outward, since it did not expand light. Chiaroscuro was not used, since shadow was forbidden as it was considered a refuge for evil. Light was considered of divine origin and conqueror of darkness, so it illuminated everything equally, with the consequence of the lack of modeling and volume in the objects, a fact that resulted in the weightless and incorporeal image that was sought to emphasize spirituality.[88] Although there is a greater interest in the representation of light, it is more symbolic than naturalistic. Just as in architecture the stained glass windows created a space where illumination took on a transcendent character, in painting a spatial staging was developed through gold backgrounds, which although they did not represent a physical space, they did represent a metaphysical realm, linked to the sacred. This "gothic light" was a feigned illumination and created a type of unreal image that transcended mere nature.[93]

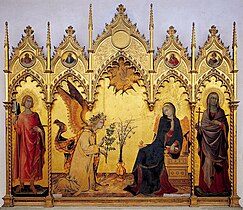

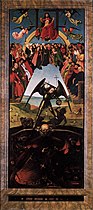

The gold background reinforced the sacred symbolism of light: the figures are immersed in an indeterminate space of unnatural light, a scenario of sacred character where figures and objects are part of the religious symbolism. Cennino Cennini (Il libro dell'Arte), compiled various technical procedures for the use of gold leaf in painting (backgrounds, draperies, nimbuses), which remained in force until the 16th century. Gold leaf was used profusely, especially in halos and backgrounds, as can be seen in Duccio's Maestà, which shone brightly in the interior of the cathedral of Siena. Sometimes, before applying the gold leaf, a layer of red clay was spread; after wetting the surface and placing the gold leaf, it was smoothed and polished with ivory or a smooth stone. To achieve more brilliance and to catch the light, incisions were made in the gilding. It is noteworthy that in early Gothic painting there are no shadows, but the entire representation is uniformly illuminated; according to Hans Jantzen, "to the extent that medieval painting suppresses the shadow, it raises its sensitive light to the power of a super-sensible light".[95] In Gothic painting there is a progressive evolution in the use of light: the linear or Franco-Gothic Gothic was characterized by linear drawing and strong chromaticism, and gave greater importance to the luminosity of flat color than to tonality, emphasizing chromatic pigment as opposed to luminous gradation. With the Italic or Trecentist Gothic a more naturalistic use of light began, characterized by the approach to the representation of depth – which would crystallize in the Renaissance with the linear perspective – the studies on anatomy and the analysis of light to achieve tonal nuance, as seen in the work of Cimabue, Giotto, Duccio, Simone Martini, and Ambrogio Lorenzetti. In the Flemish Gothic period, the technique of oil painting emerged, which provided brighter colors and allowed their gradation in different chromatic ranges, while facilitating greater detail in the details (Jan van Eyck, Rogier van der Weyden, Hans Memling, Gerard David).[96] Between the 13th and 14th centuries a new sensibility towards a more naturalistic representation of reality emerged in Italy, which had as one of its contributing factors the study of a realistic light in the pictorial composition. In the frescoes of the Scrovegni Chapel (Padua), Giotto studied how to distinguish flat and curved surfaces by the presence or absence of gradients and how to distinguish the orientation of flat surfaces by three tones: lighter for horizontal surfaces, medium for frontal vertical surfaces and darker for receding vertical surfaces. Giotto was the first painter to represent sunlight, a type of soft, transparent illumination, but one that already served to model figures and enhance the quality of clothes and objects.[97] For his part, Taddeo Gaddi – in his Annunciation to the Shepherds (Baroncelli Chapel, Santa Croce, Florence) – depicted divine light in a night scene with a visible light source and a rapid fall in the pattern of light distribution characteristic of point sources of light, through contrasts of yellow and violet.[98]  In the Netherlands, the brothers Hubert and Jan van Eyck and Robert Campin sought to capture various plays of light on surfaces of different textures and sheen, imitating the reflections of light on mirrors and metallic surfaces and highlighting the brilliance of colored jewels and gems (Triptych of Mérode, by Campin, 1425–1428; Polyptych of Ghent, by Hubert and Jan van Eyck, 1432). Hubert was the first to develop a certain sense of saturation of light in his Hours of Turin (1414-1417), in which he recreated the first "modern landscapes" of Western painting – according to Kenneth Clark.[99] In these small landscapes the artist recreates effects such as the reflection of the evening sky on the water or the light sparkling on the waves of a lake, effects that would not be seen again until the Dutch landscape painting of the 17th century. In the Ghent Polyptych (1432, Saint Bavo's Cathedral, Ghent), by Hubert and Jan, the landscape of The Adoration of the Mystic Lamb melts into light in the celestial background, with a subtlety that only the Baroque Claude of Lorraine would later achieve.[100] Jan van Eyck developed the light experiments of his brother and managed to capture an atmospheric luminosity of naturalistic aspect in his works, in paintings such as The Virgin of Chancellor Rolin (1435, Louvre Museum, Paris), or The Arnolfini Marriage (1434, The National Gallery, London), where he combines the natural light that enters through two side windows with that of a single candle lit on the candlestick, which here has a more symbolic than plastic value, since it symbolizes human life.[97] In Van Eyck's workshop, oil painting was developed, which gave a greater luminosity to the painting thanks to the glazes: in general, they applied a first layer of tempera, more opaque, on which they applied the oil (pigments ground in oil), which is more transparent, through several thin layers that let the light pass through, achieving greater luminosity, depth and tonal and chromatic richness.[101] Other Dutch artists who stood out in the expression of light were: Dirk Bouts, who in his works enhances with light the coloring and, in general, the plastic sense of the composition; Petrus Christus, whose use of light approaches a certain abstraction of the forms; and Geertgen tot Sint Jans, author in some of his works of surprising light effects, as in his Nativity (1490, National Gallery, London), where the light emanates from the body of the Child Jesus in the cradle, symbol of the Divine Grace.[102]

Modern Age ArtRenaissance The art of the Modern Age – not to be confused with modern art, which is often used as a synonym for contemporary art – began with the Renaissance, which emerged in Italy in the 15th century (Quattrocento), a style influenced by classical Greco-Roman art and inspired by nature, with a more rational and measured component, based on harmony and proportion. Linear perspective emerged as a new method of composition and light became more naturalistic, with an empirical study of physical reality. Renaissance culture meant a return to rationalism, the study of nature, empirical research, with a special influence of classical Greco-Roman philosophy. Theology took a back seat and the object of study of the philosopher returned to the human being (humanism).[103] In the Renaissance, the use of canvas as a support and the technique of oil painting became widespread, especially in Venice from 1460. Oil painting provided a greater chromatic richness and facilitated the representation of brightness and light effects, which could be represented in a wider range of shades. In general, Renaissance light tended to be intense in the foreground, diminishing progressively towards the background. It was a fixed lighting, which meant an abstraction with respect to reality, since it created an aseptic space subordinated to the idealizing character of Renaissance painting; to reconvert this ideal space into a real atmosphere, a slow process was followed based on the subordination of volumetric values to lighting effects, through the dissolution of the solidity of forms in the luminous space.[88]  During this period, chiaroscuro was recovered as a method to give relief to objects, while the study of gradation as a technique to diminish the intensity of color and modeling to graduate the different values of light and shadow was deepened. Renaissance natural light not only determined the space of the pictorial composition, but also the volume of figures and objects. It is a light that loses the metaphorical character of Gothic light and becomes a tool for measuring and ordering reality, shaping a plastic space through a naturalistic representation of light effects. Even when light retains a metaphorical reference – in religious scenes – it is a light subordinated to the realistic composition.[104] Light had a special relevance in landscape painting, a genre in which it signified the transition from a symbolic representation in medieval art to a naturalistic transcription of reality. Light is the medium that unifies all parts of the composition into a structured and coherent whole. According to Kenneth Clark, "the sun shines for the first time in the landscape of the Flight into Egypt that Gentile da Fabriano painted in his Adoration of 1423. This sun is a golden disk, which is reminiscent of medieval symbolism, but its light is already fully naturalistic, spilling over the hillside, casting shadows and creating the compositional space of the image. In the Renaissance, the first theoretical treatises on the representation of light in painting appeared: Leonardo da Vinci dedicated a good part of his Treatise on Painting to the scientific study of light. Albrecht Dürer investigated a mathematical procedure to determine the location of shadows cast by objects illuminated by point source lights, such as candlelight. Giovanni Paolo Lomazzo devoted the fourth book of his Trattato (1584) to light, in which he arranged light in descending order from primary sunlight, divine light and artificial light to the weaker secondary light reflected by illuminated bodies. Cennino Cennini took up in his treatise Il libro dell'arte the rule of Philoponus on the creation of distance by contrasts: "the farther away you want the mountains to appear, the darker you will make your color; and the closer you want them to appear, the lighter you will make the colors".[105] Another theoretical reference was Leon Battista Alberti, who in his treatise De pictura (1435) pointed out the indissolubility of light and color, and affirmed that "philosophers say that no object is visible if it is not illuminated and has no color. Therefore they affirm that between light and color there is a great interdependence, since they make themselves reciprocally visible". In his treatise, Alberti pointed out three fundamental concepts in painting: circumscriptio (drawing, outline), compositio (arrangement of the elements), and luminum receptio (illumination).[106] He stated that color is a quality of light and that to color is to "give light" to a painting. Alberti pointed out that relief in painting was achieved by the effects of light and shadow (lumina et umbrae), and warned that "on the surface on which the rays of light fall the color is lighter and more luminous, and that the color becomes darker where the strength of the light gradually diminishes." Likewise, he spoke of the use of white as the main tool for creating brilliance: "the painter has nothing but white pigment (album colorem) to imitate the flash (fulgorem) of the most polished surfaces, just as he has nothing but black to represent the most extreme darkness of the night. Thus, the darker the general tone of the painting, the more possibilities the artist has to create light effects, as they will stand out more.[107]  Alberti's theories greatly influenced Florentine painting in the mid-15th century, so much so that this style is sometimes called pittura di luce (light painting), represented by Domenico Veneziano, Fra Angelico, Paolo Uccello, Andrea del Castagno and the early works of Piero della Francesca. Domenico Veneziano, who as his name indicates was originally from Venice but settled in Florence, was the introducer of a style based more on color than on line. In one of his masterpieces, The Virgin and Child with Saint Francis, Saint John the Baptist, Saint Cenobius and Saint Lucy (c. 1445, Uffizi, Florence), he achieved a believably naturalistic representation by combining the new techniques of representing light and space. The solidity of the forms is solidly based on the light-shadow modeling, but the image also has a serene and radiant atmosphere that comes from the clear sunlight that floods the courtyard where the scene takes place, one of the stylistic hallmarks of this artist.[108] Fra Angelico synthesized the symbolism of the spiritual light of medieval Christianity with the naturalism of Renaissance scientific light. He knew how to distinguish between the light of dawn, noon and twilight, a diffuse and non-contrasting light, like an eternal spring, which gives his works an aura of serenity and placidity that reflects his inner spirituality. In Scenes from the Life of Saint Nicholas (1437, Pinacoteca Vaticana, Rome) he applied Alberti's method of balancing illuminated and shaded halves, especially in the figure with his back turned and the mountainous background. Uccello was also a great innovator in the field of pictorial lighting: in his works – such as The Battle of San Romano (1456, Musée du Louvre, Paris) – each object is conceived independently, with its own lighting that defines its corporeality, in conjunction with the geometric values that determine its volume. These objects are grouped together in a scenographic composition, with a type of artificial lighting reminiscent of that of the performing arts.[109]  In turn, Piero della Francesca used light as the main element of spatial definition, establishing a system of volumetric composition in which even the figures are reduced to mere geometric outlines, as in The Baptism of Christ (1440-1445, The National Gallery, London). According to Giulio Carlo Argan, Piero did not consider "a transmission of light, but a fixation of light", which turns the figures into references of a certain definition of space. He carried out scientific studies of perspective and optics (De prospectiva pingendi) and in his works, full of a colorful luminosity of great beauty, he uses light as both an expressive and symbolic element, as can be seen in his frescoes of San Francesco in Arezzo. Della Francesca was one of the first modern artists to paint night scenes, such as The Dream of Constantine (Legend of the Cross, 1452–1466, San Francesco in Arezzo). He cleverly assimilated the luminism of the Flemish school, which he combined with Florentine spatialism: in some of his landscapes there are luminous moonscapes reminiscent of the Van Eyck brothers, although transcribed with the golden Mediterranean light of his native Umbria.[110] Masaccio was a pioneer in using light to emphasize the drama of the scene, as seen in his frescoes in the Brancacci chapel of Santa Maria del Carmine (Florence), where he uses light to configure and model the volume, while the combination of light and shadow serves to determine the space. In these frescoes, Masaccio achieved a sense of perspective without resorting to geometry, as would be usual in linear perspective, but by distributing light among the figures and other elements of the representation. In The Tribute of the Coin, for example, he placed a light source outside the painting that illuminates the figures obliquely, casting shadows on the ground with which the artist plays. Straddling the Gothic and Renaissance periods, Gentile da Fabriano was also a pioneer in the naturalistic use of light: in the predella of the Adoration of the Magi (1423, Uffizi, Florence) he distinguished between natural, artificial and supernatural light sources, using a technique of gold leaf and graphite to create the illusion of light through tonal modeling. Sandro Botticelli was a Gothic painter who moved away from the naturalistic style initiated by Masaccio and returned to a certain symbolic concept of light. In The Birth of Venus (1483-1485, Uffizi, Florence), he symbolized the dichotomy between matter and spirit with the contrast between light and darkness, in line with the Neoplatonic theories of the Florentine Academy of which he was a follower: on the left side of the painting the light corresponds to the dawn, both physical and symbolic, since the female character that appears embracing Zephyrus is Aurora, the goddess of dawn; on the right side, darker, are the earth and the forest, as metaphorical elements of matter, while the character that tends a mantle to Venus is the Hour, which personifies time. Venus is in the center, between day and night, between sea and land, between the divine and the human.[111]  A remarkable pictorial school emerged in Venice, characterized by the use of canvas and oil painting, where light played a fundamental role in the structuring of forms, while great importance was given to color: chromaticism would be the main hallmark of this school, as it would be in the 16th century with Mannerism. Its main representatives were Carlo Crivelli, Antonello da Messina, and Giovanni Bellini. In the Altarpiece of Saint Job (c. 1485, Gallerie dell'Accademia, Venice), Bellini brought together for the first time the Florentine linear perspective with Venetian color, combining space and atmosphere, and made the most of the new oil technique initiated in Flanders, thus creating a new artistic language that was quickly imitated. According to Kenneth Clark, Bellini "was born with the landscape painter's greatest gift: emotional sensitivity to light".[112] In his Christ on the Mount of Olives (1459, National Gallery, London) he made the effects of light the driving force of the painting, with a shadowy valley in which the rising sun peeks through the hills. This emotive light is also seen in his Resurrection at the Staatliche Museen in Berlin (1475-1479), where the figure of Jesus radiates a light that bathes the sleeping soldiers. While his early works are dominated by sunrises and sunsets, in his mature production he appreciates more the full light of day, in which the forms merge with the general atmosphere. However, he also knew how to take advantage of the cold and pale lights of winter, as in the Virgin of the Meadow (1505, National Gallery, London), where a pale sun struggles with the shadows of the foreground, creating a fleeting effect of marble light.  The Renaissance saw the emergence of the sfumato technique, traditionally attributed to Leonardo da Vinci, which consisted of the degradation of light tones to blur the contours and thus give a sense of remoteness. This technique was intended to give greater verisimilitude to the pictorial representation, by creating effects similar to those of human vision in environments with a wide perspective. The technique consisted of a progressive application of glazes and the feathering of the shadows to achieve a smooth gradient between the various parts of light and shadow of the painting, with a tonal gradation achieved with progressive retouching, leaving no trace of the brushstroke. It is also called "aerial perspective", since its results resemble the vision in a natural environment determined by atmospheric and environmental effects. This technique was used, in addition to Leonardo, by Dürer, Giorgione and Bernardino Luini, and later by Velázquez and other Baroque painters. Leonardo was essentially concerned with perception, the observation of nature. He sought life in painting, which he found in color, in the light of chromaticism. In his Treatise on Painting (1540) he stated that painting is the sum of light and darkness (chiaroscuro), which gives movement, life: according to Leonardo, darkness is the body and light is the spirit, and the mixture of both is life. In his treatise he established that "painting is a composition of light and shadows, combined with the various qualities of all the simple and compound colors". He also distinguished between illumination (lume) and brilliance (lustro), and warned that "opaque bodies with hard and rough surface never generate luster in any illuminated part". The Florentine polymath included light among the main components of painting and pointed it out as an element that articulates pictorial representation and conditions the spatial structure and the volume and chromaticism of objects and figures. He was also concerned with the study of shadows and their effects, which he analyzed together with light in his treatise. He also distinguished between shadow (ombra) and darkness (tenebre), the former being an oscillation between light and darkness. He also studied nocturnal painting, for which he recommended the presence of fire as a means of illumination, and he wrote down the different necessary gradations of light and color according to the distance from the light source. Leonardo was one of the first artists to be concerned with the degree of illumination of the painter's studio, suggesting that for nudes or carnations the studio should have uncovered lights and red walls, while for portraits the walls should be black and the light diffused by a canopy. Leonardo's subtle chiaroscuro effects are perceived in his female portraits, in which the shadows fall on the faces as if submerging them in a subtle and mysterious atmosphere. In these works he advocated intermediate lights, stating that "the contours and figures of dark bodies are poorly distinguished in the dark as well as in the light, but in the intermediate zones between light and shadow they are better perceived". Likewise, on color he wrote that "colors placed in shadows will participate to a greater or lesser degree in their natural beauty according as they are placed in greater or lesser darkness. But if the colors are placed in a luminous space, then they will possess a beauty all the greater the more splendorous the luminosity".[113]