|

Later Zhou

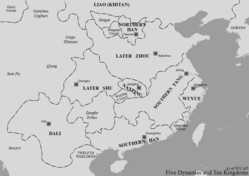

Zhou, known as the Later Zhou (/dʒoʊ/;[1] simplified Chinese: 后周; traditional Chinese: 後周; pinyin: Hòu Zhōu) in historiography, was a short-lived Chinese imperial dynasty and the last of the Five Dynasties that controlled most of northern China during the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms period. Founded by Guo Wei (Emperor Taizu), it was preceded by the Later Han dynasty and succeeded by the Northern Song dynasty. Founding of the dynastyGuo Wei, a Han Chinese, served as the Assistant Military Commissioner at the court of the Later Han, a regime ruled by Shatuo Turks. Liu Chengyou came to the throne of the Later Han in 948 after the death of the founding emperor, Gaozu. Guo Wei led a successful coup against the teenage emperor and then declared himself emperor of the new Later Zhou on New Year's Day in 951. Rule of Guo WeiGuo Wei, posthumously known as Emperor Taizu of Later Zhou, was the first Han Chinese ruler of northern China since 923. He is regarded as an able leader who attempted reforms designed to alleviate burdens faced by the peasantry. His rule was vigorous and well-organized. However, it was also a short reign. His death from illness in 954 ended his three-year reign. His adoptive son Chai Rong (also named Guo Rong) would succeed his reign. Rule of Guo RongGuo Rong, posthumously known as Emperor Shizong of Later Zhou, was the adoptive son of Guo Wei. Born Chai Rong, he was the son of his wife's elder brother. He ascended the throne on the death of his adoptive father in 954. His reign was also effective and was able to make some inroads in the south with victories against the Southern Tang in 956. However, efforts in the north to dislodge the Northern Han, while initially promising, were ineffective. He died an untimely death in 959 from an illness while on campaign. Fall of the Later ZhouGuo Rong was succeeded by his seven-year-old son upon his death. Soon thereafter, Zhao Kuangyin usurped the throne and declared himself emperor of the Great Song dynasty, a dynasty that would eventually reunite China, bringing all of the southern states into its control as well as the Northern Han by 979. Rulers

Later Zhou emperors' family tree

Currency The only series of cash coins attributed to the Later Zhou period are the Zhouyuan Tongbao (simplified Chinese: 周元通宝; traditional Chinese: 周元通寶; pinyin: zhōuyuán tōng bǎo) coins which were issued by Emperor Shizong from the year 955 (Xiande 2).[2][3] Emperor Shizong is sometimes said to have cast cash coins with the inscription Guangshun Yuanbao (simplified Chinese: 广顺元宝; traditional Chinese: 廣順元寶; pinyin: guǎng shùn yuánbǎo) during his Guangshun period title (951–953), however no authentic cash coins with this inscription are known to exist. The pattern of the Zhouyuan Tongbao is based on that of the Kaiyuan Tongbao cash coins. They were cast from melted-down bronze statues from 3,336 Buddhist temples and mandated that the citizens of Later Zhou should turn in to the government all of their bronze utensils with the notable exception of bronze mirrors, Shizong also ordered a fleet of junks to go to Korea to trade Chinese silk for copper which would be used to manufacture cash coins. When reproached for this, the Emperor uttered a cryptic remark to the effect that the Buddha would not mind this sacrifice. It is said that the Emperor himself supervised the casting at the many large furnaces at the back of the palace. The coins are assigned amuletic properties and "magical powers" because they were made from Buddhist statues and are said to particularly effective in midwifery – hence the many later-made imitations which are considered to be a form of Chinese charms and amulets. Among these assigned powers it is said that Zhouyuan Tongbao cash coins could cure malaria and help women going through a difficult labour. The Chinese numismatic charms based on the Zhouyuan Tongbao often depict a Chinese dragon and fenghuang as a pair on their reverse symbolising either a harmonious marriage or the Emperor and Empress, other images on Zhouyuan Tongbao charms and amulets include depictions of Gautama Buddha, the animals of the Chinese zodiac, and other auspicious objects.[4][5] See alsoReferencesCitations

Sources

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||