|

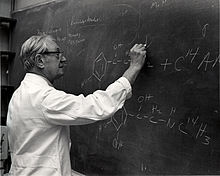

Julius Axelrod

Julius Axelrod (May 30, 1912 – December 29, 2004)[1] was an American biochemist. He won a share of the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1970 along with Bernard Katz and Ulf von Euler.[2][3][4][5] The Nobel Committee honored him for his work on the release and reuptake of catecholamine neurotransmitters, a class of chemicals in the brain that include epinephrine, norepinephrine, and, as was later discovered, dopamine. Axelrod also made major contributions to the understanding of the pineal gland and how it is regulated during the sleep-wake cycle.[6][7][8] Education and early lifeAxelrod was born in New York City, the son of Jewish immigrants from Poland, Molly (née Leichtling) and Isadore Axelrod, a basket weaver.[9] He received his bachelor's degree in biology from the College of the City of New York in 1933. Axelrod wanted to become a physician, but was rejected from every medical school to which he applied. He worked briefly as a laboratory technician at New York University, then in 1935 he got a job with the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene testing vitamin supplements added to food. While working at the Department of Health, he attended night school and received his master's in sciences degree from New York University in 1941. ResearchAnalgesic researchIn 1946, Axelrod took a position working under Bernard Brodie at Goldwater Memorial Hospital. The research experience and mentorship Axelrod received from Brodie would launch him on his research career. Brodie and Axelrod's research focused on how analgesics (pain-killers) work. During the 1940s, users of non-aspirin analgesics were developing a blood condition known as methemoglobinemia. Axelrod and Brodie discovered that acetanilide, the main ingredient of these pain-killers, was to blame. They found that one of the metabolites also was an analgesic. They recommended that this metabolite, acetaminophen (paracetamol, Tylenol), be used instead. Catecholamine research In 1949, Axelrod began work at the National Heart Institute, forerunner of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI), part of the National Institutes of Health (NIH). He examined the mechanisms and effects of caffeine, which led him to an interest in the sympathetic nervous system and its main neurotransmitters, epinephrine and norepinephrine. During this time, Axelrod also conducted research on codeine, morphine, methamphetamine, and ephedrine and performed some of the first experiments on LSD. Realizing that he could not advance his career without a PhD, he took a leave of absence from the NIH in 1954 to attend George Washington University Medical School. Allowed to submit some of his previous research toward his degree, he graduated one year later, in 1955. Axelrod then returned to the NIH and began some of the key research of his career. Axelrod received his Nobel Prize for his work on the release, reuptake, and storage of the neurotransmitters epinephrine and norepinephrine, also known as adrenaline and noradrenaline. Working on monoamine oxidase (MAO) inhibitors in 1957, Axelrod showed that catecholamine neurotransmitters do not merely stop working after they are released into the synapse. Instead, neurotransmitters are recaptured ("reuptake") by the pre-synaptic nerve ending, and recycled for later transmissions. He theorized that epinephrine is held in tissues in an inactive form and is liberated by the nervous system when needed. This research laid the groundwork for later selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), such as Prozac, which block the reuptake of another neurotransmitter, serotonin. In 1958, Axelrod also discovered and characterized the enzyme catechol-O-methyl transferase, which is involved in the breakdown of catecholamines.[10] Pineal gland researchSome of Axelrod's later research focused on the pineal gland. He and his colleagues showed that the hormone melatonin is generated from tryptophan, as is the neurotransmitter serotonin. The rates of synthesis and release follows the body's circadian rhythm driven by the suprachiasmatic nucleus within the hypothalamus. Axelrod and colleagues went on to show that melatonin had wide-ranging effects throughout the central nervous system, allowing the pineal gland to function as a biological clock. He was elected a Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1971.[11] He continued to work at the National Institute of Mental Health at the NIH until his death in 2004. Many of his papers and awards are held at the National Library of Medicine.[12] Awards and honorsAxelrod was awarded the Gairdner Foundation International Award in 1967 and the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1970. He was elected a Foreign Member of the Royal Society (ForMemRS) in 1979.[1] In 1992, he was awarded the Ralph W. Gerard Prize in Neuroscience. He was elected to the American Philosophical Society in 1995.[13] Research traineesSolomon Snyder, Irwin Kopin, Ronald W. Holz, Rudi Schmid, Bruce R. Conklin, Ron M. Burch, Juan M. Saavedra, Marty Zatz, Richard M. Weinshilboum, Michael Brownstein, Chris Felder, Lewis Landsberg, Robert Kanterman, Richard J. Wurtman.[citation needed] Personal lifeAxelrod injured his left eye when an ammonia bottle in the lab exploded; he would wear an eyepatch for the rest of his life. Although he became an atheist early in life and resented the strict upbringing of his parents' religion, he identified with Jewish culture and joined several international fights against anti-Semitism.[14] His wife of 53 years, Sally Taub Axelrod, died in 1992. At his death, on December 29, 2004, he was survived by two sons, Paul and Alfred, and three grandchildren. Political viewsAfter receiving the Nobel Prize in 1970, Axelrod used his visibility to advocate several science policy issues. In 1973 U.S. President Richard Nixon created an agency with the specific goal of curing cancer. Axelrod, along with fellow Nobel-laureates Marshall W. Nirenberg and Christian Anfinsen, organized a petition by scientists opposed to the new agency, arguing that by focusing solely on cancer, public funding would not be available for research into other, more solvable, medical problems. Axelrod also lent his name to several protests against the imprisonment of scientists in the Soviet Union. Axelrod was a member of the Board of Sponsors of the Federation of American Scientists and the International Academy of Science, Munich. See alsoReferences

Further reading

External links

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||