|

Horace Lucian ArnoldHorace Lucian Arnold (June 25, 1837 – January 25, 1915[1]) was an American engineer, inventor, engineering journalist and early American writer on management, who wrote about shop management, cost accounting, and other specific management techniques.[2] He also wrote under the names Hugh Dolnar, John Randol,[3] and Henry Roland. With Henry R. Towne, Henry Metcalfe, Emile Garcke, John Tregoning and Slater Lewis he is known as early systematizer of management of the late 19th century.[4] BiographyBorn in New York, Arnold grew up in Lafayette, Walworth County, Wisconsin. Here Arnold started his career working in machine shops. For twelve years he was journeyman machinist in western river and lake engine shops. Subsequently, he was superintendent at the Ottawa Machine Shop and Foundry; department foreman at the E. W. Bliss Company; superintendent at the Stiles & Parker Press Company of Norman C. Stiles; and designer for the Pratt and Whitney Company in Hartford, Connecticut.[5][6] In those days Arnold had also started inventing new tools. In 1858 he had patented his first invention, a marble saw.[7][8]  In the next ten years Arnold moved to work at places from Ottawa, Illinois; Grand Rapids, Michigan; Middletown, Connecticut; eventually to Brooklyn, New York, where he would stay. He continued to research and invented a range of products from "metal cutters to recorders, book binding, book stitching and book covering machines, mixers, letter locks..., piston water meters and water motors, knitting machines, 'explosive' and internal combustion engines and combustion generators, and clutches."[8] Late 1880s Arnold started his own typewriter company.[8] In the 1890s he started as a technical journalist for journals such as the Engineering Magazine, the Automobile Trade Journal, and the American Machinist.. He wrote his articles using different pen names of which Henry Roland and Hugh Dolnar were the best known.[9][10] Arnold also wrote at least three books published by the Engineering Magazine Press in New York. Arnold died of pneumonia in Detroit on January 25, 1915, at the age of 77.[1][11] An article in Business Week (1966) recalled, that "every reader of the Engineering Magazine knew what the connection was: Arnold had died on the job of tracking down the full Ford story."[12] WorkEngineering Magazine, 1895-1914In the 1890s Arnold started writing on technology and management subjects in Engineering Magazine, and would continue to contribute until his death. In 1898 H.M. Norris reviewed[13]

For this work Arnold is nowadays considered among the foremost early writers on management techniques, such as wage systems, production control and inventory control. He was among the foremost writers of the late 19th century, such as Henry R. Towne, Henry Metcalfe, John Tregoning and Slater Lewis; and among early 20th-century authors as Frederick Winslow Taylor, C.E. Knoeppel, Harrington Emerson, Clinton Edgar Woods, Charles U. Carpenter, Alexander Hamilton Church and Henry Gantt.[10] Modern Machine-Shop Economics, 1896In 1896 Arnold wrote a first series of articles for the Engineering Magazine about machine shops, entitled "Modern Machine-Shop Economics."[14] This work stretched out from production technology, production methods and factory lay-out to time studies, production planning, and machine shop management. Some of the companies still exist. Modern Machine-Shop Economics, 1896

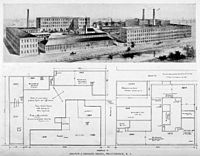

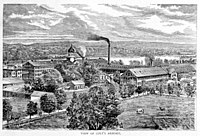

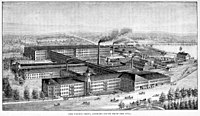

In the next years a few more series of articles on these topic would follow in the Engineering Magazine . Six examples of successful shop management, 1897In 1897 Arnold published a second series, entitled "Six examples of successful shop management."[15] Burton (1899) summarized, that these papers "giving six examples of successful shop management, wherein the influence of fair and just dealing, of isolation and environment, and of careful detailed supervision and definite contracts, upon the prosperity of the factories and the contentment of the work people are cleverly traced. The success is, however, in most cases, that of isolated works under the dominance of exceptionally skilful managers, who impress their own rectitude and personality on the establishment, rather than of any system which recommends itself for general adoption."[16] The first article recounted about the Whitin Machine Shop in Whitinsville in Northbridge, Massachusetts (see images), at its peak the largest manufacturer of textile machines in the world.[17] And the second article was about the Yale & Towne Manufacturing Co (see images), where Henry R. Towne was president at that time.[18] In those days the company faced serious labour problems, and Towne introduced a series of "measures. He ended the contract system, introduced piece rates, which he guaranteed for one year, and established systematic procedures for dealing with grievances. On new work Towne set minimum and maximum earnings levels so that piece rates, if incorrect, would not unduly punish or reward workers.[19]..."[20] Six examples of successful shop management, 1897

In the fourth article, entitled "Pre-Eminent Success of the Differential Piece Rate System", Arnold described the Taylor System as worked out by the Midvale Steel Company.[21] Especially the operation of the piece-rate system at Midvale Steel was described, and the analytic method of rate-fixing deveped by Frederick Winslow Taylor.[22] In those days the rates in the piecework system were set by the supervisor.[23][24] Burton commented, that this paper contained contains some pregnant remarks on the increase of output through the stimulus of unfettered piecework rates, and is deserving of the most grave consideration by English managers and workmen... The justice and economy of piece-work, even under fixed and absolute rates, is admirably expressed."[16] As Arnold stated:

On the whole series Kaufman (2008) commented, that "a distinctive feature of the six examples of successful shop management highlighted by [Arnold] is that they practiced a relatively benevolent and light-handed form of autocracy in which the golden rule of fair dealing and 'doing unto others' was a guiding management principle. This form of enlightened autocracy was frequently labeled 'industrial paternalism' with the idea that the company was a family, the employer played the role of the benevolent but exacting father (the paternal figure), and the employees were akin to teenage children who, with suitable guidance and discipline, would work together to produce what the family required (as on a family farm)."[26] Effective systems of finding and keeping shop costs, 1898In 1897-98 Arnold published a first series about cost keeping in machine shops, entitled "Cost-Keeping Methods in Machine-Shop and Foundry,"[27] and in 1898 he published a second series of six articles, entitled "Effective systems of finding and keeping shop costs."[28] This work contributed to the wider discussion among British and American engineers about the development of a costing system for factories. Initial contributions were made by Metcalfe (1885/86), Garcke (1887), Towne (1889), Halsey (1891),etc., and further contributions came from Bunnell, Church, Diemer, Gantt, Randolph, Oberlin Smith, Taylor, among others.[29] These discussion focussed on topics such as "costing methods, estimating, overhead allocations, economies of scale and other topics normally associated with the accounting."[29] Wells (1996) stated, that these early pioneers in the field of cost accounting, became aware of the "arbitrary nature of cost allocations... [proceeding] accountants by 50 years or more."[29] In that respect, Arnold considered these costs 'probable', yet considered the information from the system 'absolute correct.' Randolph and Diemer (1903) would speak of 'accurate costs' and 'correct' or 'accurate' information. Wells added that these "engineers (as did the accountants who followed them) failed to recognize the difference between a system that allocated all of the overhead costs "accurately"—there were no residual costs unallocated—and the arbitrary cost of production that resulted from the use of some broad allocation base such as direct wages."[29] Written records in businessArnold was known as promoter of written records in business. Arnold (1901) was convinced, that "Even if entire honesty and sincerity prevailed at all times in all business transactions, the mere differences due to variations in individual understandings of orders would render it impossible to conduct any business of magnitude on verbal specifications."[4][30] Ford Methods and the Ford Shops, 1915 Under the penname Hugh Dolnar, Arnold also wrote for the leading automotive magazine Automobile Trade Journal, where he was one of the most respected reporters.[31] Henry Ford admired his work[32] and early 1910s invited him to study his factory and write about the new production techniques at the Highland Park Ford Plant. This resulted in the book Ford Methods and the Ford Shops, which he left unfinished after his death in 1915. The engineer Fay Leone Faurote (1881-1938) finished his work, which was published in 1915 by the Engineering Magazine company, and became Arnold's best known work. This book introduced the moving assembly line to the larger audience,[32][33] explained about its slow progress,[34] and suggested that this system could be applied in any small machine factory.[35] ReceptionA short obituary in the Cycle and Automobile Trade Journal (1915) wrote:

His last work for the Automobile Trade Journal had been on the Ford Factory, the 50-page longe article "The Ford Achievement",.[37] published in April, 1914.[36] PublicationsArnold wrote some books, and many articles on shop management, cost accounting, and other specific management techniques. His books:

PatentsAbout 25 of Arnold's inventions got patented.[8] A selection:

References

External linksWikimedia Commons has media related to Horace Lucian Arnold. |