|

History of vegetarianism

The earliest records of vegetarianism as a concept and practice amongst a significant number of people are from ancient India, especially among the Hindus[1] and Jains.[2] Later records indicate that small groups within the ancient Greek civilizations in southern Italy and Greece also adopted some dietary habits similar to vegetarianism.[3] In both instances, the diet was closely connected with the idea of nonviolence toward animals (called ahimsa in India), and was promoted by religious groups and philosophers.[4] Following the Christianization of the Roman Empire in late antiquity (4th–6th centuries), vegetarianism nearly disappeared from Europe.[5] Several orders of monks in medieval Europe restricted or banned the consumption of meat for ascetic reasons but none of them abstained from the consumption of fish; these monks were not vegetarians but some were pescetarians.[6] Vegetarianism was to reemerge somewhat in Europe during the Renaissance[7] and became a more widespread practice during the 19th and 20th centuries. The figures for the percentage of the Western world which is vegetarian varies between 0.5% and 4% per Mintel data in September 2006.[8] AncientIndian subcontinentEarly Jainism and Buddhism

— Faxian, Chinese pilgrim to India (4th/5th century CE), A Record of Buddhistic Kingdoms (translated by James Legge)[9]

Jain and Buddhist sources show that the principle of nonviolence toward animals was an established rule in both religions as early as the 6th century BCE.[10][11] The Jain concept, which is particularly strict, may be even older. Lord Parshvanath, the 23rd Jain leader whom modern historians consider to be a historical figure, lived in the 9th century BCE. He is said to have preached nonviolence no less strictly than it was practiced in the Jain community during the times of Mahavira (6th century BCE).[12] Tirukkural, dated to the late 5th century CE, contains chapters on veganism or moral vegetarianism, emphasizing unambiguously on non-animal diet (Chapter 26), non-harming (Chapter 32), and non-killing (Chapter 33).[13][14] Not everyone who refused to participate in any killing or injuring of animals also abstained from the consumption of meat.[15] Hence the question of Buddhist vegetarianism in the earliest stages of that religion's development is controversial. There are two schools of thought. One says that the Buddha and his followers ate meat offered to them by hosts or alms-givers if they had no reason to suspect that the animal had been slaughtered specifically for their sake.[16] The other one says that the Buddha and his community of monks (sangha) were strict vegetarians and the habit of accepting alms of meat was only tolerated later on, after a decline of discipline.[17][18][19] The first opinion is supported by several passages in the Pali version of the Tripitaka, the opposite one by some Mahayana texts.[20] All those sources were put into writing several centuries after the death of the Buddha.[21] They may reflect the conflicting positions of different wings or currents within the Buddhist community in its early stage.[22] According to the Vinaya Pitaka, the first schism happened when the Buddha was still alive: a group of monks led by Devadatta left the community because they wanted stricter rules, including an unconditional ban on meat eating.[22] The Mahaparinibbana Sutta, which narrates the end of the Buddha's life, states that he died after eating sukara-maddava, a term translated by some as pork, by others as mushrooms (or an unknown vegetable).[23][24][25] The Buddhist emperor Ashoka (304–232 BCE) was a vegetarian,[10] and a determined promoter of nonviolence to animals. He promulgated detailed laws aimed at the protection of many species, abolished animal sacrifice at his court, and admonished the population to avoid all kinds of unnecessary killing and injury.[26][27] Ashoka has asserted protection to fauna, from his edicts:

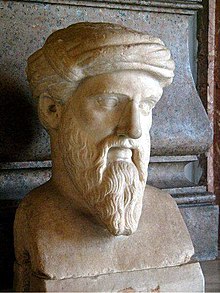

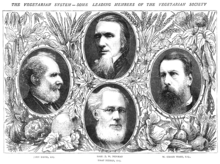

Theravada Buddhists used to observe the regulation of the Pali canon which allowed them to eat meat unless the animal had been slaughtered specifically for them.[29] In the Mahayana school some scriptures advocated vegetarianism; a particularly uncompromising one was the famous Lankavatara Sutra written in the fourth or fifth century CE.[30][31] Hinduism The vegetarian lifestyle is deeply rooted in India's historical traditions, as vegetarian cuisine existed as early as the time of the Vedas. The early history of Indian dietary practices, especially during the Vedic period, was shaped by the concept of the Guṇa – a central term in Hindu philosophy that refers to qualities or attributes. It was believed that the three Guṇas – Sattva, Rajas, and Tamas – manifested in the forms of "vegetarian," "spicy," and "meaty" foods, respectively. Brahmins, the priests of the highest caste, often adhered to vegetarian diets guided by the Sattva philosophy.[32] Philosopher Michael Allen Fox asserts that "Hinduism has the most profound connection with a vegetarian way of life and the strongest claim to fostering and supporting it."[1] In the ancient Vedic period (between 1500 and 500 BCE), although the laws permitted the consumption of some types of meat, vegetarianism was encouraged.[33] Hinduism provides several foundations for vegetarianism as the Vedas, the oldest and sacred texts of Hinduism, assert that all creatures manifest the same life force and therefore merit equal care and compassion.[34] A number of Hindu texts place injunctions against meat-eating and others like the Ramayana and Mahabharata advocate for a vegetarian diet.[1] In Hinduism, killing a cow is traditionally considered a sin.[35] Vegetarianism was, and still is, mandatory for Hindu yogis, both for the practitioners of Hatha Yoga[36] and for the disciples of the Vaishnava schools of Bhakti Yoga (especially the Gaudiya Vaishnavas). A bhakta (devotee) offers all his food to Vishnu or Krishna as prasad before eating it.[37] Only vegetarian food can be accepted as prasad.[38] According to Yogic thought, saatvik food (pure or having a good impact on the body) is meant to calm and purify the mind "enabling it to function at its maximum potential" and keep the body healthy. Saatvik foods consist of "cereals, fresh fruit, vegetables, legumes, nuts, sprouted seeds, whole grains, and milk taken from a cow, which is allowed to have a natural birth, life, and death including natural food, after satiating the needs of milk of its calf".[39] Many Vaishnava schools avoid vegetables such as onion, garlic, leek, radish, carrot, brinjal (eggplant), bottle gourd, mushrooms, red lentils, etc., as they are considered to have non-saatvik effects on the body. Shankar Narayan suggests that the origin of vegetarianism in India developed from the idea that balance needed to be restored. He claims, "Along with the development in civilization, savagery also increased, and those who were helpless and voiceless among both humans and non-human animals were more and more exploited and killed to satiate human needs and greed, thus disturbing the balance of nature. But there were also many serious attempts to bring back humanity to sanity and restore balance from time to time." He also notes that the idea of living in harmony with nature became central to the rulers and kings.[39] ZoroastrianismFollowers of Ilm-e-Kshnoom, a school of Zoroastrian thought found in India, practice vegetarianism, and follow other currently non-traditional opinions.[40] There have been various theological statements supporting vegetarianism in Zoroastrianism's history and claims that Zoroaster was vegetarian.[41] Mediterranean Basin Ancient GreeceIn Ancient Greece during Classical antiquity, the vegetarian diet was called abstinence from beings with a soul (Ancient Greek: ἀποχὴ ἐμψύχων).[44] As a principle or deliberate way of life it was always limited to a rather small number of practitioners belonging to specific philosophical schools or certain religious groups.[45] The earliest European/Asian Minor references to a vegetarian diet occur in Homer (Odyssey 9, 82–104) and Herodotus (4, 177), who mention the Lotophagi (Lotus-eaters), an indigenous people on the North African coast, who according to Herodotus lived on nothing but the fruits of a plant called lotus. Diodorus Siculus (3, 23–24) transmits tales of vegetarian peoples or tribes in Ethiopia, and further stories of this kind are narrated and discussed in ancient sources.[46] The earliest reliable evidence for vegetarian theory and practice in Greece dates from the 6th century BCE. The Orphics, a religious movement spreading in Greece at that time, may have practiced vegetarianism.[43] It is unclear whether the Greek religious teacher Pythagoras actually advocated vegetarianism,[42] and it is more likely that Pythagoras only prohibited certain kinds of meat.[42] Later writers presented Pythagoras as prohibiting meat altogether.[42] Eudoxus of Cnidus, a student of Archytas and Plato, writes that "Pythagoras was distinguished by such purity and so avoided killing and killers that he not only abstained from animal foods, but even kept his distance from cooks and hunters".[42] Behind Pythagoras’ rejection of eating meat were ethical considerations. He believed that animals possess both intelligence and passion (the critical elements for sentience) and because of that their mistreatment was unethical.[47] Pythagoras additionally forbade his students from consuming eggs and wearing woolen clothing.[48] The followers of Pythagoras (called Pythagoreans) did not always practice strict vegetarianism, but at least their inner circle did. For the general public, abstention from meat was a hallmark of the so-called "Pythagorean way of life".[49] Both Orphics and strict Pythagoreans also avoided eggs and shunned the ritual offerings of meat to the gods which were an essential part of traditional religious sacrifice.[50] In the 5th century BCE the philosopher Empedocles distinguished himself as a radical advocate of vegetarianism specifically and of respect for animals in general.[51] A fictionalized portrayal of Pythagoras appears in Book XV of Ovid's Metamorphoses,[52] in which he advocates a form of strict vegetarianism.[52] It was through this portrayal that Pythagoras was best known to English-speakers throughout the early modern period[52] and, prior to the coinage of the word "vegetarianism", vegetarians were referred to in English as "Pythagoreans".[52]  The question of whether there are any ethical duties toward animals was hotly debated, and the arguments in dispute were quite similar to the ones familiar in modern discussions on animal rights.[53] Vegetarianism was usually part and parcel of religious convictions connected with the concept of transmigration of the soul (metempsychosis).[54] There was a widely held belief, popular among both vegetarians and non-vegetarians, that in the Golden Age of the beginning of humanity mankind was strictly non-violent. In that utopian state of the world hunting, livestock breeding, and meat-eating, as well as agriculture were unknown and unnecessary, as the earth spontaneously produced in abundance all the food its inhabitants needed.[55] This myth is recorded by Hesiod (Works and Days 109sqq.), Plato (Statesman 271–2), the famous Roman poet Ovid (Metamorphoses 1,89sqq.), and others. Ovid also praised the Pythagorean ideal of universal nonviolence (Metamorphoses 15,72sqq.). Almost all the Stoics were emphatically anti-vegetarian[56] (with the prominent exception of Seneca).[57] They insisted on the absence of reason in brutes, leading them to conclude that there cannot be any ethical obligations or restraints in dealing with the world of irrational animals.[58] As for the followers of the Cynic school, their extremely frugal way of life entailed a practically meatless diet, but they did not make vegetarianism their maxim.[59] In the Platonic Academy, the scholarchs (school heads) Xenocrates and (probably) Polemon pleaded for vegetarianism.[60] In the Peripatetic school Theophrastus, Aristotle's immediate successor, supported it.[61] Some of the prominent Platonists and Neo-Platonists in the age of the Roman Empire lived on a vegetarian diet. These included Apollonius of Tyana, Plotinus, and Porphyry.[62] Porphyry wrote a treatise On Abstinence from Eating Animals, the most elaborate ancient pro-vegetarian text known to us.[63] Porphyry believed that animals are aware and capable of evaluating situations, have memory, and can communicate. He urged that by consuming meat, the body becomes corrupt and unhealthy, leading to obesity. Porphyry maintained that killing an animal is no different from taking the life of a human being – and thus became one of the first to state that animal life is equal to that of a human.[64] Among the Manicheans, a major religious movement founded in the third century CE, there was an elite group called Electi (the chosen) who were Lacto-Vegetarians for ethical reasons and abided by a commandment which strictly banned killing. Common Manicheans called Auditores (Hearers) obeyed looser rules of nonviolence.[65] JudaismA small number of Jewish scholars throughout history have argued that the Torah provides a scriptural basis for vegetarianism, now or in the Messianic Age.[66] Some writers assert that the Jewish prophet Isaiah was a vegetarian.[67][68][69] A number of ancient Jewish sects, including early Karaite sects, regarded the eating of meat as prohibited, at least while Israel was in exile,[70] and medieval scholars such as Joseph Albo and Isaac Arama regarded vegetarianism as a moral ideal, out of a concern for the moral character of the slaughterer.[71] East AsiaChina With the spread of Buddhism, vegetarian cuisine also became popular in China. Records show that as early as the Song dynasty (10th century), monks were consuming "vegetarian meat" made from tofu. These dishes, known as "Fang Hun Cai" ("meat imitation dishes"), arose because monasteries had to adapt to the expectations of pilgrims and patrons, who preferred meat-based meals. As a result, vegetarian dishes were prepared to imitate meat dishes. Even today, one can find numerous meat substitute dishes in China, such as fried "crab meat" made from potatoes and carrots in Shanghai, or "twice-cooked pork" without meat in Sichuan.[72] The religions of Chinese Buddhism and Taoism require monks and nuns to follow a vegetarian diet free of eggs and onions. Since abbeys were often self-sufficient, this effectively meant they adhered to a vegan diet. Many religious orders also avoid harming plant life by not eating root vegetables. This practice is not merely ascetic but reflects the belief in Chinese spirituality that animals possess immortal souls, and that a grain-based diet is the healthiest for humans. In Chinese folk religions, as well as the aforementioned faiths, people often eat vegan on the 1st and 15th of the month, and on the eve of Chinese New Year. Some non-religious people follow this practice too, similar to the Christian observance of Lent and abstaining from meat on Fridays. While the percentage of people who are permanently vegetarian in China is similar to that in the modern English-speaking world, this proportion has remained relatively unchanged for a long time. Many people adopt a vegan diet temporarily, believing it helps atone for sins. Foods like seitan, tofu skin, and meat alternatives made from seaweed, root vegetable starch, and tofu all originated in China, becoming popular due to the periodic abstention from meat. In China, it's possible to find vegetarian substitutes for everything from seafood to ham, all prepared without eggs.[73] The Thai (เจ) and Vietnamese (chay) terms for vegetarianism also originate from the Chinese term for a lenten diet. China's vegetarian culture remained relatively unchanged until the Republican era (1912–1949), when political reformers such as Sun Yat-Sen and Cai Yuanpei promoted vegetarianism as a more hygienic and cost-effective diet to strengthen the nation. However, this secular movement had little impact on traditional eating habits.[74] Japan In 675, the use of livestock and the consumption of some wild animals (horse, cattle, dogs, monkeys, birds) was banned in Japan by Emperor Tenmu, due to the influence of Buddhism.[75] Subsequently, in the year 737 of the Nara period, the Emperor Seimu approved the eating of fish and shellfish. During the twelve hundred years from the Nara period to the Meiji Restoration in the latter half of the 19th century, Japanese people enjoyed vegetarian-style meals. They usually ate rice as a staple food as well as beans and vegetables. It was only on special occasions or celebrations that fish was served. Over this period, the Japanese people (particularly Buddhist monks) developed a vegetarian cuisine called shōjin-ryōri which was native to Japan. ryōri means cooking or cuisine, while shojin is a Japanese translation of virya in Sanskrit, meaning "to have the goodness and keep away evils".[76] In 1872 of the Meiji restoration,[77] as part of the opening up of Japan to Western influence, Emperor Meiji lifted the ban on the consumption of red meat.[78] The removal of the ban encountered resistance and in one notable response, ten monks attempted to break into the Imperial Palace. The monks asserted that due to foreign influence, large numbers of Japanese had begun eating meat and that this was "destroying the soul of the Japanese people." Several of the monks were killed during the break-in attempt, and the remainder were arrested.[77][79] Orthodox ChristianityIn Eastern Orthodox Christianity (Greece, Cyprus, Russia, Serbia and other Orthodox countries), adherents eat a diet completely free of animal products for fasting periods (except for honey) as well as all types of oil and alcohol, during a strict fasting period. The Ethiopian Orthodox Church prescribes a number of fasting (tsom, Ge'ez: ጾም ṣōm, excluding any kind of animal products, including dairy products and eggs) periods, including Wednesdays, Fridays, and the entire Lenten season, so Ethiopian cuisine contains many dishes that are vegan. Christian antiquity and Middle Ages

The leaders of the early Christians in the apostolic era (James, Peter, and John) were concerned that eating food sacrificed to idols might result in ritual pollution. The only food sacrificed to idols was meat.[citation needed] The Apostle Paul emphatically rejected that view which resulted in division of an Early Church (Romans 14:2-21; compare 1 Corinthians 8:8-9, Colossians 2:20-22).[80][81] Many early Christians were vegetarian such as Clement of Alexandria, Origen, Jerome, John Chrysostom, Basil the Great, and others.[82] Some early church writings suggest that Matthew, Peter, and James were vegetarian.[citation needed] The historian Eusebius writes that the Apostle "Matthew partook of seeds, nuts and vegetables, without flesh."[83] The philosopher Porphyry wrote an entire book entitled On Abstinence from Animal Food which compiled most of the classical thought on the subject.[84][85] In late antiquity and in the Middle Ages many monks and hermits renounced meat-eating in the context of their asceticism.[86] The most prominent of them was St Jerome († 419), whom they used to take as their model.[87] The Rule of St Benedict (6th century) allowed the Benedictines to eat fish and fowl, but forbade the consumption of the meat of quadrupeds unless the religious was ill.[88] Many other rules of religious orders contained similar restrictions of diet, some of which even included fowl, but fish was never prohibited, as Jesus himself had eaten fish (Luke 24:42-43). The concern of those monks and nuns was frugality, voluntary privation, and self-mortification.[89] William of Malmesbury writes that Bishop Wulfstan of Worcester (d. 1095) decided to adhere to a strict vegetarian diet simply because he found it difficult to resist the smell of roasted goose.[90][91] Saint Genevieve, the Patron Saint of Paris, is mentioned as having observed a vegetarian diet—but as an act of physical austerity, rather than out of concern for animals. Medieval hermits, at least those portrayed in literature, may have been vegetarians for similar reasons, as suggested in a passage from Sir Thomas Malory's Le Morte d'Arthur: 'Then departed Gawain and Ector as heavy (sad) as they might for their misadventure, and so rode till that they came to the rough mountain, and there they tied their horses and went on foot to the hermitage. And when they were come up, they saw a poor house, and beside the chapel a little courtelage, where Nacien the hermit gathered worts, as he which had tasted none other meat of a great while.'[92] John Passmore claimed that there was no surviving textual evidence for ethically motivated vegetarianism in either ancient and medieval Catholicism or in the Eastern Churches. There were instances of compassion to animals, but no explicit objection to the act of slaughter per se. The most influential theologians, St Augustine and St Thomas Aquinas, emphasized that man owes no duties to animals.[5] Although St. Francis of Assisi described animal beings with mystic language, contemporary sources do not claim that he practised or advocated vegetarianism.[5][93] Many ancient intellectual dissidents, such as the Encratites, the Ebionites, and the Eustathians who followed the fourth century monk Eustathius of Antioch, considered abstention from meat-eating an essential part of their asceticism.[94] Medieval Paulician Adoptionists, such as the Bogomils ("Friends of God") of the Thrace area in Bulgaria and the Christian dualist Cathars, also despised the consumption of meat.[95] Early modern period EuropeIt was during the European Renaissance that vegetarianism reemerged in Europe as a philosophical concept based on an ethical motivation. Among the first figures who supported it were Leonardo da Vinci (1452–1519)[96] and Pierre Gassendi (1592–1655).[97] In the 17th century the paramount theorist of the meatless or Pythagorean diet was the English writer Thomas Tryon (1634–1703), who published the vegetarian text The Way to Health, Long Life and Happiness in 1683.[98] Subsequently, the Romantic poets advocated vegetarianism.[99] In 1699, English writer John Evelyn (1620 –1706) published the vegetarian cookbook Acetaria: A Discourse of Sallets.[100] Scottish physician George Cheyne (1672–1743) was a vegetarian and authored An Essay of Health and Long Life, first published in 1724.[101] Italian physician Antonio Cocchi (1695–1758) authored the book Del vitto pitagorico per uso della medicina in 1743. It was translated by Robert Dodsley into English as The Pythagorean Diet, of Vegetables Only, Conducive to the Preservation of Health, and the Cure of Diseases in 1745.[102][103][104] Opposing viewsOn the other hand, influential philosophers such as René Descartes[105] (1596–1650) and Immanuel Kant[106] (1724–1804) were of the opinion that there cannot be any ethical duties whatsoever toward animals—though Kant also observes that "He who is cruel to animals becomes hard also in his dealings with men. We can judge the heart of a man by his treatment of animals." By the end of the 18th century in England the claim that animals were made only for man's use (anthropocentrism) was still being advanced, but no longer carried general assent. Very soon, it would disappear altogether.[107] United StatesIn the United States, there were small groups of Christian vegetarians in the 18th century. Sébastien Rale (1657 –1724) was a French Catholic priest in an Abenaki town in Maine who wrote a 1722 letter that described his strict ascetic vegetarianism.[108] The best known 18th century vegetarian community in the U.S. was the Ephrata Cloister in Pennsylvania, a religious community founded by Conrad Beissel in 1732.[109] Writer and abolitionist Benjamin Lay (1682 – 1759) was a vegetarian.[110] Benjamin Franklin became a vegetarian at the age of 16, but later on he reluctantly returned to meat eating.[111] He later introduced tofu to America in 1770.[112] James Gower (1772-1855) of Maine was a lifelong vegetarian.[113] Colonel Thomas Crafts Jr. (1740-1799), who was a painter and Boston Tea Party participant, was a vegetarian.[114][115] 19th centuryVegetarianism was frequently associated with cultural reform movements, such as temperance and anti-vivisection. It was propagated as an essential part of "the natural way of life." Some of its champions sharply criticized the civilization of their age and strove to improve public health.[116] Great Britain During the Age of Enlightenment and in the early nineteenth century, England was the place where vegetarian ideas were more welcome than anywhere else in Europe, and the English vegetarians were particularly enthusiastic about the practical implementation of their principles.[117] In England, vegetarianism was strongest in the northern and middle regions, specifically urbanized areas.[118] As the movement spread across the country, more working-class people began to identify as vegetarians, though still a small number in comparison to the number of meat eaters.[119] Groups were established all across England, but the movement failed to gain popular support and was drowned out by other, more exciting, struggles of the late-nineteenth century.[120] In 1802, Joseph Ritson authored An Essay on Abstinence from Animal Food, as a Moral Duty.[121] Reverend William Cowherd founded the Bible Christian Church in 1809. He advocated vegetarianism as a form of temperance, and his organisation was one of the philosophical forerunners of the Vegetarian Society.[122] Martha Brotherton authored Vegetable Cookery, the first vegetarian cookbook, in 1812.[123][124] A prominent advocate of an ethically motivated vegetarianism in the early 19th century was the poet Percy Bysshe Shelley (1792–1822).[125] He was influenced by John Frank Newton's Return to Nature, or, Defence of the Vegetable Regimen (1811), and he published an essay on the subject in 1813, A Vindication of Natural Diet.[126] The first Vegetarian Society of the modern western world was established in England in 1847.[127] The Society was founded by the 140 participants of a conference at Ramsgate and by 1853 had 889 members.[128] By the end of the century, the group had attracted almost 4,000 members.[129] After its first year, alone, the group grew to 265 members that ranged from ages 14 to 76.[130] English vegetarians were a small but highly motivated and active group. Many of them believed in a simple life and "pure" food, humanitarian ideals and strict moral principles.[131] Not all members of the Vegetarian Society were "Cowherdites", though they constituted about half of the group.[130] The Cornishman newspaper reported in March 1880 that a vegetarian restaurant had existed in Manchester for some years and one had just opened in Oxford Street, London.[132] ClassClass played prominent roles in the Victorian vegetarian movement. There was somewhat of a disconnect when the upper-middle class attempted to reach out to the working and lower classes. Though the meat industry was growing substantially, many working class Britons had mostly vegetarian diets out of necessity rather than out of the desire to improve their health and morals. The working class did not have the luxury of being able to choose what they would eat and they believed that a mixed diet was a valuable source of energy.[133] WomenTied closely with other social reform movements, women were especially visible as the "mascot". When late-Victorians sought to promote their cause in journal, female angels or healthy English women were the images most commonly depicted.[134] Two prominent female vegetarians were Elizabeth Horsell, author of a vegetarian cookbook and a lecturer (and wife of William Horsell), and Jane Hurlstone. Hurlstone was active in Owenism, animal welfare, and Italian nationalism as well. Though women were regularly overshadowed by men, the newspaper the Vegetarian Advocate noted that women were more inclined to do work in support of vegetarianism and animal welfare than men, who tended to only speak on the matter. In a domestic setting, women promoted vegetarianism though cooking vegetarian dishes for public dinners and arranging entertainment that promoted the cause.[135] Outside of the domestic sphere, Victorian women edited vegetarian journals, wrote articles, lectured, and wrote cookbooks. Of the 26 vegetarian cookbooks published during the Victorian Age, 14 were written by women.[136] In 1895, The Women's Vegetarian Union was established by Alexandrine Veigele, a French woman living in London. The organization aimed to promote a 'purer and simpler' diet and they regularly reached out to the working class.[137] The morality arguments behind vegetarianism in Victorian England drew idealists from various causes together. Specifically, many vegetarian women identified as feminists. In her feminist utopia, Herland (1915), Charlotte Perkins Gilman imagined a vegetarian society. Margaret Fuller also advocated for vegetarianism in her work, Women of the Nineteenth Century (1845).[138] She argued that when women are liberated from domestic life, they would help transform the violent male society, and vegetarianism would become the dominant diet. Frances Power Cobbe, a co-founder of the British Union for the Abolition of Vivisection, identified as a vegetarian and was a well-known activist for feminism. Many of her colleagues in the first-wave feminist movement also identified as vegetarians.[139] United States In 1835, Asenath Nicholson authored the first American vegetarian cookbook.[140] In 1845, the vegetarian newspaper The Pleasure Boat began publication.[141] In the United States, Reverend William Metcalfe (1788–1862), a pacifist and a prominent member of the Bible Christian Church, preached vegetarianism.[142] He and Sylvester Graham, the mentor of the Grahamites and inventor of the Graham crackers, were among the founders of the American Vegetarian Society in 1850.[143] In 1838, Dr. William Alcott published "Vegetable Diet: As Sanctioned by Medical Men, and by Experience in All Ages." The book was reprinted in 2012, and journalist Avery Yale Kamila called it "a seminal work in the cannon of American vegetarian literature."[144] Ellen G. White, one of the founders of the Seventh-day Adventist Church, became an advocate of vegetarianism, and the Church has recommended a meatless diet ever since.[145] Dr. John Harvey Kellogg (of corn flakes fame), a Seventh-Day Adventist, promoted vegetarianism at his Battle Creek Sanitarium as part of his theory of "biologic living".[146] American vegetarians such as Isaac Jennings, Susanna W. Dodds, M. L. Holbrook and Russell T. Trall were associated with the natural hygiene movement.[147] Other countries The German-speaking world played a key role in the international vegetarian movement. In 1908, the International Vegetarian Union (IVU) was founded in Dresden, and the German Vegetarierbund Deutschland, established in 1867 in Nordhausen, is the second-oldest vegetarian organization in the world.[148] In Germany, the politician, publicist, and revolutionary Gustav Struve (1805–1870) was a key figure in the early vegetarian movement. Inspired by Jean-Jacques Rousseau's treatise Emile: or, On Education, Struve promoted vegetarianism as part of his broader vision for social reform.[149] In the late 19th century, numerous vegetarian associations were founded in Germany, with the Order of the Golden Age gaining particular prominence beyond the food reform movement.[citation needed] Historian Albert Wirz notes that the trend toward vegetarianism before World War I was partly a reaction to the social upheavals caused by industrialization and globalization.[150] In addition to rejecting meat, various dietary approaches like Rohkost (raw food diet) and Vollwerternährung (whole food nutrition) emerged. As Pierre Bourdieu argued in his work Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste, taste preferences became markers of cultural and social distinction among various social groups.[151] The modern vegetarian movement also saw the involvement of figures like Elisabeth Förster-Nietzsche and her husband Bernhard Förster, who founded the utopian colony Nueva Germania in Paraguay in 1886. Their project aimed to promote vegetarianism and Aryan superiority, though the vegetarian aspect was short-lived.[152][153] In Tsarist Russia, vegetarianism also took on a significant political meaning. According to Slavist Peter Brang, vegetarian restaurants and associations were seen as symbols of intellectual opposition, heavily influenced by the teachings of Leo Tolstoy.[154] Tolstoy (1828–1910) was one of the most prominent advocates of vegetarianism in Russia.[155][156] Traditional Russian cuisine already distinguished between fasting (vegetarian) and festive (meat-based) dishes, offering a wide variety of options suitable for vegetarians.[citation needed] 20th centuryThe International Vegetarian Union, a union of the national societies, was founded in 1908. In the Western world, the popularity of vegetarianism grew during the 20th century as a result of nutritional, ethical, and more recently, environmental and economic concerns. The IVU's 1975 World Vegetarian Congress in Orono, Maine caused a significant impact on to the country's vegetarian movement.[157] Henry Stephens Salt[158] (1851–1939) and George Bernard Shaw (1856–1950) were famous vegetarian activists.[159] In 1910, physician J. L. Buttner authored the vegetarian book, A Fleshless Diet which argued that meat is dangerous and unnecessary.[160] Cranks opened in Carnaby Street, London, in 1961, as the first successful vegetarian restaurant in the UK. Eventually there were five Cranks restaurants in London which closed in 2001.[161][162] The Indian concept of nonviolence had a growing impact in the Western world. The model of Mahatma Gandhi, a strong and uncompromising advocate of nonviolence toward animals, contributed to the popularization of vegetarianism in Western countries.[163] The study of Far-Eastern religious and philosophical concepts of nonviolence was also instrumental in the shaping of Albert Schweitzer's principle of "reverence for life", which is still today a common argument in discussions on ethical aspects of diet. But Schweitzer himself started to practise vegetarianism only shortly before his death.[164] Singer-songwriter, Morrissey, discussed the idea of vegetarianism on his song and album Meat is Murder. His widespread fame and cult status contributed to the popularity of meat-free lifestyles.[165] The 1932 magazine The Vegetarian and Fruitarian was published in Lewiston, Idaho. It promotes ethics, ideals, culture, health, and longevity. At the time, the vegetarian and raw food movements were, in part, tied to feminism. It was viewed as a way to free women from the confines of the kitchen and allow them to pursue other activities and interests.[166] In August 1944, several members of the British Vegetarian Society asked that a section of its newsletter be devoted to non-dairy vegetarianism. When the request was turned down, Donald Watson, secretary of the Leicester branch, set up a new quarterly newsletter in November 1944 called it The Vegan News. Dorothy Morgan and Donald Watson, co-founders of the Vegan Society, chose the word vegan themselves,[167][168][169] based on "the first three and last two letters of 'vegetarian'" because it marked, in Mr Watson's words, "the beginning and end of vegetarian". Current situation Today, Indian vegetarians, who are primarily lacto-vegetarians, are estimated to make up more than 70 percent of the world's vegetarians. They make up 20–42 percent of the population in India, while less than 30 percent are regular meat-eaters.[170][171][172] According to a study by U.S.-based anthropologist Balmurli Natrajan and India-based economist Suraj Jacob, "only" about 20% of the Indian population is vegetarian.[173] Surveys in the U.S. have found that roughly 6% of adults never eat meat, poultry or fish (defined as vegetarian, and includes vegans) with about half of those (3% of the population) never eating meat, poultry, fish, dairy, or eggs (defined as vegan). Similar surveys in 1994 and 1997 show the number of vegetarians in the U.S. was about one percent. Additionally, 2021 surveys show about 5% of U.S. 8-17 year olds never eat meat, fish, or poultry and about 2% never eat meat, fish, poultry, dairy, eggs.[174][175][176][177] In 2013, PS 244 in Queens became the first public school in New York to adopt an all-vegetarian menu. Meals still meet the required USDA protein standards.[178] In 2014, the Jain pilgrimage destination of Palitana City in Indian state of Gujarat became the first city in the world to be legally vegetarian. It has outlawed, or made illegal, the buying and selling of meat, fish and eggs, and also related jobs or work, such as fishing and penning 'food animals'.[179][180][181][182] According to a 2018 survey, about 25 percent of evening meals consumed in the UK are meat and fish free.[183] Historians of vegetarianism

Writers of advocacy histories See also

Notes

Sources

Further reading

|