|

Harry Croswell

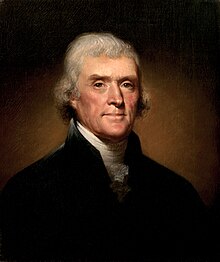

Harry Croswell (June 16, 1778 – March 13, 1858) was a crusading political journalist, a publisher, author, and an Episcopal Church clergyman. Though largely self-educated, he received an honorary degree of A. M. from Yale College in 1817, an honorary Doctorate of Divinity from Trinity College, Hartford, Connecticut, in 1831 – an institution he co-founded – established the first public lectures in New Haven, and founded an evening school for the education of adult African-Americans in the city. He was a key figure in first amendment battles over freedom of the press and religious freedom. After abandoning politics for religion, he became the much respected Rector of Trinity Church on the Green in New Haven, Connecticut, for forty-three years, growing his church and establishing seven new churches within the original limits of his parish. Though he published fourteen books, and wrote newspaper articles as an editor and journalist weekly for eleven years, he is best known as an author for being the first person to define the word cocktail in print. LifeEarly lifeCroswell was born in West Hartford, Connecticut, on June 16, 1778. His immigrant ancestor Thomas Croswell (1633 – 1682) left Staffordshire, England, at the age of 22, and sailed to Boston, according to a biographer, "on account of the tumultuous state of affairs in that country, about the time of Cromwell's usurpation of the supreme power."[1] The family thrived: they eventually owned a farm with a large house or "mansion" on Prospect Hill in Somerville, Massachusetts, near Boston, which was later used by General George Washington as his headquarters during the 11-month siege of the British occupied city.[2] Harry Croswell was one of eight children of Caleb Croswell (1735 – 1806) and Hannah Kellogg (1739 – 1829). Croswell's father, the sea captain and merchant Captain Caleb Croswell, was a member of the Connecticut militia at the time of the Revolutionary War. He fought in the disastrous Battle of Brooklyn and was captured by the British, who imprisoned him on one of the infamous British prison-ships.  The grim conditions in the ships ruined his health, and left the family impoverished. As a consequence, the Croswells were forced to send their children out to apprentice in a profession at an early age. Thomas O'Hara Croswell was apprenticed to the law school founder Tapping Reeve, though he later became a physician. Mackay Croswell was apprenticed to Hudson & Goodwin, printers of the Hartford Courant, and Archibald Croswell was apprenticed to a tanner. Harry Croswell, the fourth eldest son, was sent at age 10 as a servant in exchange for tutoring to a fellow native of West Hartford, the then lawyer but future lexicographer, Noah Webster.[3] The arrangement lasted only a few months. Croswell was then tutored by the Rev. Dr. Nathen Perkins, the West Haven Congregationalist minister, before being sent to Warren, Connecticut, as apprentice clerk in a store in the small town. Croswell's older brothers Thomas and Mackay had moved to the then frontier town of Catskill, New York, on the banks of the Hudson River. There they opened a book and print shop in 1790. Harry left Warren and joined his brothers as an apprentice printer.[4] Mackay started a newspaper called The Catskill Packet in 1792. In the tradition of Benjamin Franklin, another man apprenticed to his brother, Croswell contributed anonymous humorous articles under the pseudonym "Titus Touchwood". His contributions were well written, satiric, partisan and very popular. His combination of high-minded politics (the Titus) and fiery, even savage indignation over injustice and folly (the Touchwood), made Croswell a man of influence in upstate New York.[5] This "led to the recognition of his promise as a writer and finally to his installment in the editorial chair":[6] In 1800, Croswell's name appeared alongside his brother as editor of the paper, now renamed The Western Constellation.[7]  Mackay and Harry Croswell in their Catskill print shop mentored two other famous future journalists, whose rivalry would define New York state and national politics for half a century to come: Harry's nephew Edwin Croswell, the editor of the Albany, New York-based Democratic Party organ, the Albany Argus, was one of the founding members of the so-called "Albany Regency" who helped elect Martin van Buren president. Thurlow Weed was a rival publisher to Edwin Croswell; as a founder and influential leader of the Republican party, he helped elect Abraham Lincoln president.[8]  In August 1800, Harry Croswell married Susan Sherman of New Haven, Connecticut. They would eventually have seven children together.[9] In 1801, the young couple moved across the Hudson River to the town of Hudson, New York, a rapidly expanding deep port river town that would become the third largest port in the state. With two partners, Ezra Sampson, a retired Congregational minister, and George Chittenden, a paper maker, Croswell founded a book store and a print shop in the rapidly growing town. There he published books, and along with Ezra Sampson, edited the Columbia County, New York, newspaper The Balance and Columbian Repository. Battling for freedom of the pressNew York was the swing state in the 1800 election that saw President Thomas Jefferson elected by one vote in the electoral college. Harry Croswell was a staunch Federalist, one of those who opposed Jefferson. When Connecticut newspaper editor Charles Holt moved to Hudson and founded the Democratic-Republican Party paper The Bee, Croswell countered by founding the Federalist paper The Wasp.[10] Croswell's political humor and darting jabs and stings at the President, New York Governor George Clinton, Attorney General Ambrose Spencer, and the rest of the Jefferson party apparatus down to the local sheriff and editor Holt, were so effective, that it was feared he would influence the election of 1804 against Jefferson. Jefferson wrote to one of his party's governors:

The renowned case of the People v. Croswell began when Croswell published on September 9, 1802, an attack on Jefferson. The state's Democratic-Republican attorney General Ambrose Spencer indicted Croswell for a seditious libel as:

The attempt to intimidate Croswell by prosecution for criminal libel backfired. It instead "resulted in the greatest advancement in press freedom in the history of America."[13] Croswell refused to back down, even after losing his first January 1803 trial at Claverack court house to political judges and packed juries. Though defended by local Federalist layers, including his friend William Peter Van Ness, he lost the second appeal trail under prominent anti-Federalist Justice Morgan Lewis in June 1803 as well. Despite facing enormous fines and jail, he kept up a barrage of attacks in his newspaper, and insisted on a third trial. It would be held at the New York Supreme court in Albany.  On February 13, 1804, the greatest Federalist lawyer, Alexander Hamilton, himself a newspaper editor as well, came up from New York to argue for the defense in the final trial in front of the New York Supreme Court. Croswell's lawyers based their case on the precept that "Truth is a defense against libel". Justice Lewis again presided, and was unlikely to overrule his own previous ruling, so all three judges would have to vote to overturn the lower court's conviction. Persuaded by Hamilton's eloquence and forensic analysis, the single Federalist Justice James Kent was joined by Justice Thompson and Justice Henry Brockholst Livingston in voting for Croswell. For a short time it seemed Croswell and Hamilton had triumphed. However, Justice Lewis abruptly adjourned the proceedings. When the court reconvened, Justice Livingston announced he had changed his opinion, and now upheld the conviction. Two years later, on November 10, 1806, on the occasion of the next available position opening, Livingston was appointed to the U.S. Supreme court. Croswell's conviction stood.  However, Justice Lewis was running for governor, and prosecuting journalists for telling the truth was unpopular. Croswell was never sentenced. Though he was eventually granted a new trial it never occurred since it was soon rendered moot. Even though Croswell and Hamilton had lost the case, the watching New York assemblymen who filled the galleries during the famous trial were so impressed by Hamilton's defense and Croswell's courage, that in 1805 they changed the state law on libel.[14] Eventually, the other states followed, establishing the precept that truth was a defense against libel, when published with "good motives, and for justifiable ends."[15] Croswell continued to publish his paper. He was repeatedly sued not for seditious libel but for civil libel in a series of less well-known cases. Tried repeatedly by political judges and packed juries, and often losing, Croswell never surrendered or retreated. In 1806, he was sued by Solomon Southwick, the publisher of the rival newspaper Albany Register, the official printer for the New York government, for printing a cartoon showing "Sir Solomon Faucet" as a man plucking a goose identified as "the public". Former prosecutor Ambrose Spencer was now a trial judge; he convicted and fined Croswell. But it was not the Democratic-Republican party machine with its presidents, governors, attorneys general, justices, judges, prosecutors, lawyers, sheriffs, local officials, and party newspaper editors, that finally sank Croswell and drove him from publishing and politics. In the spring of 1811, Croswell was "unable to discharge a small debt to a creditor who was also a leading Federalist.[16] The Federalist, an Albany, New York, lawyer, sued, and Croswell was incarcerated until he could pay the debt. Disgusted now by both parties, he swore off politics. Influenced by the Second Great Awakening since 1809, he now "carefully examined the subject of the Christian ministry; and this examination led to his full conformity to the Episcopal Church, and he was baptized in St. Peter's Church, Albany, on Sunday, July 19, 1812."[17] On May 8, 1814, Bishop John Hobart of New York ordained Croswell a deacon, and he was placed in charge of Christ Church, Hudson, New York. Separation of church and state in ConnecticutIn the summer of 1814, Harry and Susan Croswell visited Mrs. Croswell's family in New Haven. The Rector of Trinity Episcopal Church on the Green in New Haven, the Rev. Henry Whitlock, was stricken with a fatal illness, and Deacon Croswell was asked to preach.[18] After Whitlock died, Croswell as asked to take on the duties of leading the church. He took the pulpit on January 1, 1815, and five months later on June 6, 1815, he was consecrated a priest in Christ Church, Middletown, Connecticut, by Bishop Griswold.[19][20]  New Haven had long been the center of the established Congregationalist church in Connecticut. It was the home of Yale, known as "the School of the Prophets" for its fierce Puritan orthodoxy.[21] The Puritans had fiercely resisted an Anglican church in the town since the town's founding in 1638. Relations between the Episcopalian minority and the Congregationalist majority had somewhat improved from the previous century, when mob actions, whippings, oppressive taxes, and restrictive laws were used to suppress Episcopalians in the state. At a town meeting in December 1812, the town granted the Trinity parish permission to build a new Trinity Church on the town Green. The church was designed by the architect Ithiel Town in the Gothic style. It was so impressive an edifice, it would launch the Gothic Revival style in North America. The cornerstone was laid in 1814. The church was consecrated at a public ceremony in 1816, which also saw Croswell installed as Rector of the church. However, in taking over the parish, Croswell had stepped into a major denominational controversy. The Congregationalist assembly, to protect their legislative majority, beginning in 1804 had passed a series of bills limiting suffrage – including banning blacks and those with no property, or even those with mortgaged property, from voting. In 1814, they reneged on a deal to give $60,000 to Congregationalist Yale and $10,000 to an Episcopal college in Cheshire, Connecticut, giving Yale $20,000 and the Episcopal College nothing. They then refused to grant a charger to the Episcopal college. Angry at their treatment, in 1815 the Federalist Episcopalians joined with the Democratic-Republicans to form the Toleration Party. They won the 1817 elections, obtaining a slim majority in the lower house and electing former Federalist Oliver Wolcott Jr. as governor, but did not take over the upper house. Expecting to win the upper house the next year, the Toleration Party began plans to call a constitutional convention to revoke the establishment of the church in the old Connecticut Charter. The much loved charter dated back to the Connecticut Royal Charter of 1662, signed by King Charles II, which was based on the Fundamental Orders of 1639, that in turn was based on a sermon given by the Rev. Thomas Hooker to the assembly in 1638, the year of Hartford's founding. Hooker in his sermon not only gave Connecticut a relatively democratic if established church charter, but a tradition of the Anniversary Election Sermon, where a prominent clergyman would be appointed to deliver a sermon to the governing bodies of the state. For 180 years, the clergyman appointed to give the politically important sermon had been a Congregationalist minister. In 1818, Governor Wolcott instead chose the Episcopalian and ex-Federalist Harry Croswell to deliver the sermon. Having become disgruntled with not only the two parties, but party politics in general, Croswell did not deliver a partisan exhortation or preach the usual political bromides; instead he argued fiercely for the separation of church and state. In his "distinguishing line" sermon,[22] he preached that citizens, state officials, and clergy, must render unto Caesar, the things which be Caesar's, but they must also render unto God, the things which be God's; they must respect the boundary between them by not crossing into each other's territory. The sermon was very well received; four editions were funded and printed that year by the assembly.[23] The day after the sermon, the Assembly voted 81 to 80 that a simple majority would be enough to ratify the charter.[24] In October, the new constitution disestablishing the church was ratified by a slender majority. Parish minister Obeying his own precept, Croswell never publicly commented on politics nor voted in an election in the 43 years he was Rector of Trinity parish. He rarely even mentioned the political issues of the day in the diary he kept for most of the years he held his office.[25] Croswell's 5,300 page diary, begun in 1821 when he was 41, is a largely untapped treasure found in manuscript form at the Yale library. The historian Franklin Bowditch Dexter in "The Rev. Harry Croswell, D.D., and his Diary", called it "a remarkable record of individual activity, and of the shrewd comments of a critical observer on persons and events within his daily experience."[26] According to the African-American history scholar Randall K. Burkett, Rector Harry Croswell was known to minister to blacks at a time when other white clergy did not. Among the American diocesan clergy, Burkett notes that "none had more extensive or intimate acquaintance either with his own black parishioners or with a larger number of the twenty-two antebellum African-American Episcopal clergy than did the Reverend Harry Croswell," and that Croswell "all but singlehandedly ministered among the black population of New Haven."[27] His charitable works in the city included co-founding Washington College in New Haven (now Trinity College in Hartford, Connecticut), New Haven's first Orphanage, several night schools, Sunday schools and the Colonization Society. He was also a trustee and secretary of the General Theological Society.[28] His diary recounts an extraordinary life of pastoral visits and care.[29] Yale historian Dexter, who knew Croswell, observed that

When he died, a local newspaper summed up his career:

First published definition of cocktail Croswell may be most famous for printing the first definition of the word "cocktail". In the Balance and Columbian Repository of May 13, 1806, after being queried by a reader on his use of the word in the previous week's paper, he wrote:

Works by CroswellBooks

Manuscripts

Newspapers 1800-1811

References

External links

Further reading

|

||||||||||