|

Georgi Pulevski

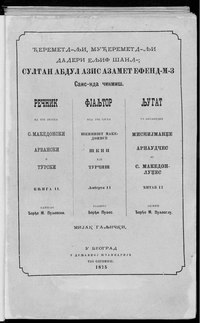

Georgi Pulevski, sometimes also Gjorgji, Gjorgjija Pulevski or Đorđe Puljevski (Macedonian: Ѓорѓи Пулевски or Ѓорѓија Пулевски, Bulgarian: Георги Пулевски, Serbian: Ђорђе Пуљевски; 1817 – 13 February 1893) was a Mijak[1][2] writer and revolutionary. Pulevski was born in Galičnik, he trained as a stonemason and later became a self-taught writer. He is known today as the first author to express the idea of a distinct Macedonian nation and Macedonian language.[3] LifePulevski was born in the village of Galičnik in the Mijak tribal region in 1817.[1] As a seven-year-old, he went to Danubian Principalities with his father as a migrant worker (pečalbar).[4] He was trained as a stonemason.[5] According to popular legends, Pulevski was engaged in a hajduk in the area of Golo Brdo as a youth.[citation needed] At the age of 45, Pulevski fought as a member of the First Bulgarian Legion in 1862 against the Ottoman siege at Belgrade.[6][7] He also participated in the Serbian–Ottoman War in 1876, and then in the Russo-Turkish War of 1877–78 as part of the Bulgarian Volunteer Corps,[8] which led to the Liberation of Bulgaria; during the latter, he was a voivode of a unit of Bulgarian volunteers,[9][10][11] taking part in the Battle of Shipka Pass.[12] He also participated as a volunteer in the Kresna-Razlog Uprising (1878–79),[8] which aimed at the unification of Ottoman Macedonia with Bulgaria.[13] In an application for a veteran pension to the Bulgarian Parliament in 1882,[14] he expressed his regret about the failure of the unification of Ottoman Macedonia with Bulgaria. In 1883, aged 66, Pulevski received a government pension in recognition of his service as a Bulgarian volunteer. Pulevski settled in the village of Progorelec, near Lom, Bulgaria, where he received gratuitously agricultural land from the state. Later he moved to Kyustendil.[15] Pulevski died in Sofia in 13 February 1893.[16][17] Works  Puevski authored Dictionary of Four Languages in 1873,[18] where he identified the vernacular Slavic language of Macedonia as "Serbo-Albanian".[19] In 1875, Pulevski published Dictionary of Three Languages (Rečnik od tri jezika, Речник од три језика) in Belgrade. It was a trilingual conversational manual composed in "question-and-answer" style in three parallel columns, in Macedonian, Albanian and Turkish, all three written in Cyrillic.[20] Pulevski chose to write in the local Macedonian rather than the Bulgarian standard based on eastern Tarnovo dialects. The basis of his language was his native Galičnik dialect but with certain and unsystematic concessions to the central Macedonian dialects.[21] It was an attempt to use a supra-dialectal language. Pulevski stated that the Macedonians were a separate nation and advocated for the Macedonian language.[3] It was the first work that publicly claimed Macedonian to be a separate language.[22] However, there is no exclusive connection of nation, language, territory and statehood in the work, which is different from the ideas in the later work On Macedonian Matters by Krste Misirkov.[23] Pulevski incorporated Kuzman Shapkarev's 1868 primer Elementary Knowledge for Little Children into the work.[21] He acknowledged Macedonia as a multilingual and multiethnic region. The adjective "Macedonian" was not reserved exclusively for the Slavic inhabitants of Macedonia.[20]

His next published works were a revolutionary poem, Samovila Makedonska (Macedonian Fairy), published in 1878,[25] and a Macedonian Song Book in two volumes, published in 1879, which contained both folk songs collected by Pulevski and some original poems by himself.[16] The former was re-published by Shapkarev in 1882 in the journal Maritsa.[25] In 1880, Pulevski published Slavjano-naseljenski makedonska slognica rečovska (Grammar of the language of the Slavic Macedonian population), a work that is known as the first attempt at a grammar of Macedonian. In it, Pulevski systematically contrasted his language, which he called našinski ("our language") or slavjano-makedonski ("Slavic-Macedonian") with both Serbian and Bulgarian.[26][full citation needed] All records of this book were lost during the first half of 20th century and only discovered again in the 1950s in Sofia. Owing to the writer's lack of formal training as a grammarian and dialectologist, it is considered of limited descriptive value; however, it has been characterized as "seminal in its signaling of ethnic and linguistic consciousness but not sufficiently elaborated to serve as a codification."[27] He also wrote about the places where the Mijaks were concentrated, their migrations and the Mijak region.[17] In his last grammar work Jazitshnica, soderzsayushtaja starobolgarski ezik, uredena em izpravlena da se uchat bolgarski i makedonski sinove i kerki; (Grammar, containing Old Bulgarian language, arranged and corrected to be taught to Bulgarian and Macedonian sons and daughters), he considered the Macedonian dialects to be old Bulgarian and the differences between the two purely geographical.[28][29] By 1893, Pulevski had largely completed Slavjanomakedonska opšta istorija (Slavic Macedonian General History), a large manuscript with around 1000 pages.[18] He stated that he wrote the manuscript "in the Slavic-Macedonian dialect (narečenije) so that it could be understood by all the Slavs of the peninsula." Much space was reserved for the Nemanjids, as well as Saint Sava, who was described as holy. For him, the Serbian tsars, like the Bulgarian tsars, were foreigners, described as ruling over "Macedonian regions."[30] He identified the Ottoman Macedonia from which he originated with ancient Macedonia and considered the Macedonian Slavs to be ancient inhabitants of the Balkan peninsula.[18] Ancestry, identification and legacy According to anthropological study, his surname is of Vlach origin, as is the case with several other surnames in Mijak territory, which contain the Vlach suffix -ul (present in Pulevci, Gugulevci, Tulevci, Gulovci, Čudulovci, etc.) This opens the possibility they are ancestors of Slavicized Vlachs, migrants from an Albanian settlement.[31] It is possible that Pulevski's ancestors settled Galičnik from Pulaj, a small maritime village, near Velipojë, at the end of the 15th century, hence the surname Pulevski.[citation needed] Pulevski claimed that the Macedonians were descendants of the ancient Macedonians. This opinion was based on the claim that Philip II and Alexander III were of Slavic origin and thus this confirmed the ancient ancestry of the modern Macedonians.[19] He considered the Mijaks to be a subgroup of the Macedonians.[18] However, his Macedonian self-identification was ambiguous. Pulevski viewed Macedonian identity as being a regional phenomenon, similar to Herzegovinians and Thracians.[19] Pulevski himself identified as a mijak galički (a "Mijak from Galičnik", 1875),[2] sometimes described himself as a "Serbian patriot"[19] and also viewed his ethnic designation as "Bulgarian from the village of Galičnik",[32][33] thus he changed his self-identification several times during his lifetime.[34] In his grammatical works, he included neologisms that were not included in modern Macedonian and opted for a phonological orthography inspired by the work of Vuk Karadžić.[35] Linguist Victor Friedman regards Pulevski as a "complex and modern personality that very well understood the complexities of ethnical-national and civilian-national affiliations in the multilingual and multicultural environment of Macedonia."[23] His work Slavic Macedonian General History was published by the Macedonian Academy of Sciences and Arts in 2003. A monument of him was placed in the center of Skopje in 2011.[18] In North Macedonia, he is celebrated as a contributor in the "National Rebirth".[8] Despite Pulevski being an early adherent of Macedonism,[36][37] because of his pro-Bulgarian military activity, in Bulgaria he is regarded as a Bulgarian.[38][39][40] According to Tchavdar Marinov, of the Bulgarian Academy of Sciences,[41][42] there are reasons to interpret the case of Pulevski as a lack of clear national identity by him, while his numerous self-identifications reveal unclear Macedonian nationhood.[43] List of works

References

Sources

External links

|

||||||||||