|

French Imperial Army (1804–1815)The French Imperial Army (French: Armée Impériale) was the land force branch of the French imperial military during the Napoleonic era. HistoryThe beginnings of the Imperial Army were seeded in the reorganisation of the French Army in 1803, which helped pave the way for the well-known French-style army organisation. Under this reorganisation, the old-style military district system was reorganised so that it included the new departments. These districts were known as 'Military Divisions', or divisions militaires, which were tasked with local administration of garrisons, recruitment, and providing National Guard and local forces for invasion. The Imperial Army was divided into three separate types of commands: the largest was the Grande Armée, and its equivalent 'Field Armies', the next smallest were the Corps of Observation which were tasked with overseeing regions with strategic importance and providing rearguards where necessary, the next smallest was the 'Field Corps' which provided the actual fighting potential with the Field Armies, and finally, the Military Districts, as previously described. In 1814, following the Abdication of Napoleon, the army was quickly redesignated as the Royal Army (Armée Royale), and the structure (for the most part) remained, though with regimental name changes and slight uniform changes. After the Return of Napoleon in 1815, almost the entirety of the army (with the exception of some of the Royal Guard (formerly Napoleon's Imperial Guard)) went over to his side along with the majority of its staff. Though the 1815 campaign was a disaster for France, it is still seen by many military historians as a success, as France was able to form several field armies and win multiple battles, with almost no preparation whatsoever. After Napoleon's second abdication, some elements of the army refused to give up, including the Armée de l'Ouest fighting an insurrection in the Vendée, the Corps of Observation of the Alpes, and the Imperial Guard (including the Minister of War, Maréchal Louis-Nicolas Davout, who retired westward to join the hastily formed Armée de la Loire. However, following the end of the Hundred Days, the remainder of the Armée de la Loire was disbanded along with any troops of the Army. The only remaining elements were the board of directors and those soldiers who had no families and were too old to leave. Part of King Louis XVIII's plan to remove the imperial stain was to completely reconstitute the army on a new regional basis and destroy the imperialist esprit-de-corps.[2][3] This marked the effective disbandment of the Imperial Army. Method of conscriptionThe French "Levée en masse" method of conscription brought around 2,300,000 French men into the Army between the period of 1804 and 1813.[4] To give an estimate of how much of the population this was, modern estimates range from 7 to 8% of the population of France proper, while the First World War used around 20 to 21%.[5] Command staffThe French Imperial Army was commanded, as its predecessors by the Supreme Commander-in-Chief, who was Emperor Napoleon Bonaparte from 1804, and in 1815. Under him sat the effective commander of the Army, the Minister of War (Ministre de la Guerre).[citation needed] Below is a list of the officers who held the position. Commander-in-Chief

Minister of WarThe duties of the Minister of War were described by historian Ronald Pawley as follows: "... he was responsible for all matters such as personnel, the ministerial budget, the Emperor's orders regarding troop movements within the Empire, the departments of artillery and engineers, and prisoners of war". When the first Minister, Louis-Alexandre Berthier was on campaign during the Ulm campaign, three members of the ministry replaced him as effective minister. Monsieur Denniée pére, became effective acting minister, Monsieur Gérard became responsible for the movements of units stationed within the borders of France (Intendent General of the Army), and Monsieur Tabarié, Director General of the Personnel Department.[6]

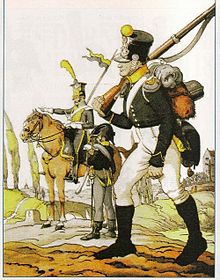

Types of unitsImperial GuardThe Imperial Guard (Garde Impériale) was the senior branch of the army, consisting of the senior troops and those who had distinguished themselves during battle, however (rather ironically) the guard consisted of some of the youngest regiments of the army. Their history is thus relatively short and simple compared to the ancient regiments of the line, many of which were raised in the 16th century. The life span of most of the guard regiments was also very short: a royal decree of 12 May 1814 (just after the Treaty of Fontainebleau) completely disbanded the Young Guard, and the units were broken up and distributed among the line. Certain units were attached to the guard in 1813, for example, the Saxon Life Grenadier Guards (Saxe Leibgrenadiergarde) and a battalion of Polish grenadiers,[11] but these were not part of the guard and did not wear the guard button. The guard was separated into three 'echelons', of which each consisted many different types of units, these consisted of the Old Guard, the Middle Guard, and the Young Guard. This effectively made the guard an independent fighting corps with everything from its own staff down to its own support units. InfantryThe infantry during the Napoleonic era provided the majority of the fighting force while on campaign. The nucleus of the army was formed in 1803, when the old 'royalist term' of Régiment replaced the 'republican style' Demi-Brigade, which subsequently referred to provisional units only. At the time, only some 90 regiments existed, the majority of them consisting of three battalions. By 1804, each battalion had been obliged to convert one of its fusilier companies into voltigeurs, thus augmenting the French light infantry establishment.[12] The war/peace establishment of a grenadier or carabinier company was 3/3 officers and 83/75 men. All other companies had 3 officers and 123 men in wartime; the peace establishments of men were 75 for fusiliers, 68 for chasseurs, and 123 for voltigeurs. Including the staff, a battalion had 700 men in peacetime and 1,100 in war. A regiment of two battalions would have 46 officers and 1,375 men in peacetime and 38 officers and 2,162 men in war; a regiment of three battalions would have 39 officers and 2,054 men in peacetime and 42 officers and 3,234 in war.[13] The line and light infantry battalion organisations were standardised to the class one grenadier, one voltigeur, and four fusilier companies by an order of 18 February 1808. That same day, Napoleon decreed that each line and light infantry regiment was to consist of one depot and four field battalions, with the depot acting as the recruitment and reserve unit.[13] Line InfantryThe line infantry was the best-known and most valuable infantry branch within the Imperial Army. The line infantry also had the most regiments throughout the war, with the following an abbreviated list of all regiments:

From 1792 till 14 March 1804, a line infantry regiment consisted of three battalions: 2 x Field battalions (8 x Fusilier and 1 x Grenadier Companies), and the Depot Battalion. On 20 September 1804, the line infantry battalions were modified by the conversion of one of the 8 fusilier companies to voltigeurs; in the fact, the most agile, smallest men in each fusilier company were concentrated into the new company.[13] During this period, a depot battalion consisted of a senior captain who was mounted, one depot captain, one 'Quartermaster Treasurer', and 4 x Fusilier Companies.[14] GrenadiersGrenadiers had historically been the tallest and most experienced. These soldiers would line up in straight lines and advance to 5–10 feet of the enemy and throw grenades, of which very few ever actually exploded. However, by the mid-18th century, these troops became elite infantry and were placed on the right of the line, indicating they were the most experienced and held in high regard.[14] Light InfantryFrance began to experiment with light infantry in 1740 and several legions were raised by 1749. At the same time, a battalion of Chasseurs à Pied (literally Hunters on Foot) was attached to each of the six newly raised regiments of Chasseurs à Cheval (literally Hunters on Horses/ Mounted Hunters). In 1788 these battalions were separated from the cavalry, and six more were raised to give 12 Chasseurs battalions in the army. They were designed to perform scouting duties and to act as advance and rear guards.[15] Below is an abbreviated list of the regiments of Régiment(s) Légère (Light Infantry Regiments):

ChasseursOn 14 March 1803, under that year's reform, it was ordered that each light infantry battalion was to consist of one Carabinier (Grenadier equivalent), eight Chasseur (Fusilier equivalent), and one Voltigeur.[13] Chasseurs effectively had the same role of the fusiliers, but were shorter and were quickly and typically more agile.[14] CavalryBy decree of the emperor, cavalry typically were between a fifth and a sixth of the Grande Armée. Cavalry regiments of 800–1,200 men were made up of three or four escadrons of two companies each, plus supporting elements. In light cavalry and dragoon regiments, the first company of every regiment's first escadron, was always designated as 'elite', with presumably, the best men and horses. In the revolution's wake, the cavalry suffered the greatest from the loss of experienced aristocratic officers and NCOs still loyal to the Ancien Régime. Consequently, the quality of French cavalry drastically declined. Napoleon rebuilt the branch, turning it into arguably the finest in the world. Until 1812, it was undefeated in any large engagements above the regimental level. There were two primary types of cavalry for different roles, heavy and light. The French fielded inferior cavalry as compared to their Hessian, Baden, Polish, British, Prussian and Austrian counterparts. However, French cavalry won many more engagements than their enemies, with many reasons combining to achieve this. One factor was certainly their superior organization, at higher levels, to most of their opponents. The French command structure and organization made it more likely that a French cavalry had reserves available, and the ability to direct them to exploit a break in the enemy line or plug a gap in their own, or counterattack a victorious enemy. Their discipline and tactics of using larger formations (cavalry divisions and cavalry corps) impressed even the most bitter enemies of France.[14] In peacetime, the regiments of dragoons, lancers, chasseurs and hussars had colour of horses according to squadron:[14]

However, already during the campaign in 1805, only some colonels insisted on keeping up these peacetime practices. The heavy cavalry, carabiniers and cuirassiers, rode on black horses.[14] Heavy CavalryHorse CarabiniersThe elite among all French heavy cavalry line formations, the two regiments of mounted carabiniers had a very similar appearance with the mounted grenadiers of the Imperial Guard; bearskins, long blue coats, etc. and were mounted exclusively on black horses prior to 1813. They were largely used in identical manner to the Cuirassiers, but being (initially) unarmored, they were less suited for close-quarters, melee combat. Unarmored heavy cavalry was the norm in Europe during most of the Napoleonic Wars, with the French being the first to reintroduce the back-and-breastplate. In 1809, appalled by their mauling at the hands of Austrian Uhlans, Napoleon ordered that they be given armour. The carabinier's refusal to copy the less elite cuirassiers resulted in them being given special armor, with their helmets and cuirasses being sheathed in bronze for added visual effect. But this did not prevent them from being defeated by Russian cuirassiers at Borodino in 1812, and panicking before Hungarian hussars at Leipzig the following year. CuirassiersThe heavy cavalry, wearing a heavy cuirass (breastplate) and helmets of brass and iron and armed with straight long sabres, pistols, and later carbines. Like medieval knights, they served as mounted shock troops. Because of the weight of their armour and weapons, both the trooper and the horse had to be big and strong, and could put a lot of force behind their charge. Though the cuirass could not protect against direct musket fire, it could deflect ricochets and shots from long range, and offered some protection from pistol shots. More importantly, the breastplates protected against the swords and lances of opposing cavalry. Napoleon often combined all of his cuirassiers and carabiniers into a cavalry reserve, to be used at the decisive moment of the battle. In this manner, they proved to be an extremely potent force on the battlefield. The British, in particular, who mistakenly believed the cuirassiers were Napoleon's bodyguards, and would later come to adapt their distinctive helmets and breastplates for their own Household Cavalry. There were originally 25 cuirassier regiments, reduced to 12 by Napoleon initially who later added three more. At the beginning of his rule, most of the cuirassier regiments were severely understrength, so Napoleon ordered the best men and horses to be allocated to the first 12 regiments, while the rest were reorganised into dragoons. Below is an abbreviated list of cuirassier regiments:

DragoonsThe medium-weight mainstays of the French cavalry, although considered heavy cavalry, were used for battle, skirmishing, and scouting. They were highly versatile being armed not only with distinctive straight swords, but also muskets with bayonets enabling them to fight as infantry as well as mounted, though fighting on foot had become increasingly uncommon for dragoons of all armies in the decades preceding Napoleon. The versatility of a dual-purpose soldier came at the cost of their horsemanship and swordsmanship often not being up to the same standards as those of other cavalry. Finding enough large horses proved a challenge. Some infantry officers were even required to give up their mounts for the dragoons, creating resentment towards them from this branch as well. There were 25, later 30, dragoon regiments. In 1815, only 15 could be raised and mounted in time for the Waterloo campaign. Below is an abbreviated list of dragoon regiments:

Light cavalryHussarsThese fast, light cavalrymen were the eyes, ears, and egos of the Napoleonic armies. They regarded themselves as the best horsemen and swordsmen (beau sabreurs) in the entire Grande Armée. This opinion was not entirely unjustified and their flamboyant uniforms reflected their panache. Tactically, they were used for reconnaissance, skirmishing, and screening for the army to keep their commanders informed of enemy movements while denying the enemy the same information and pursuing fleeing enemy troops. Armed only with curved sabres and pistols, they had reputations for reckless bravery to the point of being almost suicidal. It was said by their most famous commander General Antoine Lasalle that a hussar who lived to be 30 was truly an old guard and very fortunate. Lasalle was killed at the Battle of Wagram at age 34. There were 10 regiments in 1804, with an 11th added in 1810 and two more in 1813. Below is an abbreviated list of regiments (unless stated all formerly existed prior to 1803):

Horse HuntersThese were light cavalry identical to hussars in arms and role. But, unlike the chasseurs of the Imperial Guard and their infantry counterparts, they were considered less prestigious or elite. Their uniforms were less colourful as well, consisting of infantry-style shakos (in contrast to the fur busby worn by some French hussars), green coats, green breeches, and short boots. They were, however, the most numerous of the light cavalry, with 31 regiments in 1811, six of which comprised Flemish, Swiss, Italians and Germans. These cavalry was composed of chasseurs but on the horse, they could load into melee or shoot as light infantry. Below is an abbreviated list of regiments (unless stated all formerly existed prior to 1803):

LancersSome of the most feared cavalry in the Grande Armée were the Polish lancers of the Vistula Uhlans. Nicknamed Hell's Picadors or Los Diablos Polacos (The Polish Devils) by the Spanish, these medium and light horse (Chevaux-Légers Lanciers) cavalry had near equal speed to the hussars, shock power almost as great as the cuirassiers, and were nearly as versatile as the dragoons. They were armed with, as their name indicates, lances along with sabres and pistols. Initially, French ministers of war insisted on arming all lancers identically. Real battlefield experience, however, proved that the Polish way of arming only the first line with lances while the second rank carried carbines instead was much more practical and thus was adopted. Lancers were the best cavalry for charging against infantry squares, where their lances could outreach the infantry's bayonets, (as was the case with Colborne's British brigade at Albuera in 1811) and also in hunting down a routed enemy. Their ability to scour and finish off the wounded without ever stepping off their saddle created perfect scenes of horror for the enemy. They could be deadly against other types of cavalry as well, most famously demonstrated by the fate of Sir William Ponsonby and his Scots Greys at Waterloo. Excluding those of the Guard, there were 9 lancer regiments. Below is an abbreviated list of regiments (unless stated all were formed on 18 June 1811):

ArtilleryThe emperor was a former artillery officer, and reportedly said "God fights on the side with the best artillery."[16] As such, French cannons were the backbone of the French Imperial Army, possessing the greatest firepower of the three arms and hence the ability to inflict the most casualties in the least amount of time. The French guns were often used in massed batteries (or grandes batteries) to soften up enemy formations before being subjected to the closer attention of the infantry or cavalry. Superb gun-crew training allowed Napoleon to move the weapons at great speed to either bolster a weakening defensive position or else hammer a potential break in enemy lines. Besides superior training, Napoleon's artillery was also greatly aided by the numerous technical improvements to French cannons by General Jean Baptiste de Gribeauval which made them lighter, faster, and much easier to sight, as well as strengthened the carriages and introduced standard-sized calibres. In general, French guns were 4-pounders, 8-pounders, or 12-pounders and 6-inch (150 mm) howitzers with the lighter calibres being phased out and replaced by 6-pounders later in the Napoleonic Wars. French cannons had brass barrels and their carriages, wheels, and limbers were painted olive green. Superb organisation fully integrated the artillery into the infantry and cavalry units it supported, yet also allowed it to operate independently if the need arose. There were two basic types, Artillerie à pied (foot artillery) and Artillerie à cheval (horse artillery). Foot artilleryAs the name indicates, these gunners marched alongside their guns, which were, of course, pulled by horses when limbered (undeployed). Hence, they travelled at the infantry's pace or slower. In 1805, there were eight, later ten, regiments of foot artillery in the Grande Armée plus two more in the Imperial Guard, but unlike cavalry and infantry regiments, these were administrative organisations. The main operational and tactical units were the batteries (or companies) of 120 men each, which were formed into brigades and assigned to the divisions and corps.

Battery personnel included not only gun crews, NCOs, and officers, but drummers, trumpeters, metal workers, woodworkers, ouvriers, fouriers, and artificers. They would be responsible for fashioning spare parts, maintaining and repairing the guns, carriages, caissons and wagons, as well as tending the horses and storing munitions. Below is an abbreviated list of regiments (again, there were really only administrative units):

Horse artilleryThe cavalry were supported by the fast-moving, fast-firing light guns of the horse artillery. This arm was a hybrid of cavalry and artillery with their crews riding either on the horses or on the carriages into battle. Because they operated much closer to the front lines, the officers and crews were better armed and trained for close-quarters combat, mounted or dismounted much as were the dragoons. Once in position, they were trained to quickly dismount, unlimber (deploy), and sight their guns, then fire rapid barrages at the enemy. They could then quickly limber (undeploy) the guns, remount, and move on to a new position. To accomplish this, they had to be the best trained and most elite of all artillerymen. The horse batteries of the Imperial Guard could go from riding at full gallop to firing their first shot in just under a minute. After witnessing such a performance, an astounded Duke of Wellington remarked, "They move their cannon as if it were a pistol!" There were 6 administrative regiments of horse artillery plus one in the Guard. In addition to the batteries assigned to the cavalry units, Napoleon would also assign at least one battery to each infantry corps or, if available, to each division. Their abilities came at a price, however, as horse batteries were very expensive to raise and maintain. Consequently, they were far fewer in number than their foot counterparts, typically constituting only one-fifth of the artillery's strength. It was a boastful joke among their ranks that the emperor knew every horse gunner by name. Besides better training, horses, weapons, and equipment, they used far more ammunition. Horse batteries were given twice the ammo ration of the foot, three times that of the Guard. Below is an abbreviated list of regiments (again, there were really only administrative units):

LogisticsOf all the types of ammunition used in the Napoleonic Wars, the cast iron, spherical, round shot was the staple of the gunner. Even at long range when the shot was travelling relatively slowly it could be deadly, though it might appear to be bouncing or rolling along the ground relatively gently. At short range, carnage could result.[20] In the French Imperial Army, the ammunition columns were grouped into Equipment Trains or Train des Équipages. In 1809, there were more than 11 battalions, with a 12th forming in Commercy, including two reserve battalions being formed in Spain. Each battalion was composed of 6 companies, of which each was commanded by a captain and oversaw some 44 other ranks.[21][22] A battalion headquarters comprised 4 x officers (a captain in command), 5 x NCOs, and 5 x craftsmen. Each company numbered 1 x officer (sous-lieutenant), 7 x NCOs, 4 x craftsmen, 80 x drivers, 36 x vehicles, and 161 x horses.[23] Below is a list of the equipment train battalions:[24]

Artillery trainThe Artillery Train (Train d'Artillerie), was established by Napoleon in January 1800. Its function was to provide the teamsters and drivers who handled the horses that hauled the artillery's vehicles.[25] Prior to this, the French, like all other period armies, had employed contracted, civilian teamsters who would sometimes abandon the guns under fire, rendering them immobile, rather than risk their lives or their valuable teams of horses.[26] Its personnel, unlike their civilian predecessors, were armed, trained, and uniformed as soldiers. Apart from making them look better on parade, this made them subject to military discipline and capable of fighting back if attacked. The drivers were armed with a carbine, a short sword of the same type used by the infantry, and a pistol. They needed little encouragement to use these weapons, earning surly reputations for gambling, brawling, and various forms of mischief. Their uniforms and coats of grey helped enhance their tough appearance. But their combativeness could prove useful as they often found themselves attacked by Cossacks and Spanish and Tyrolian guerillas. Each train d'artillerie battalion was originally composed of 5 companies. The first company was considered elite and assigned to a horse artillery battery; the three "centre" companies were assigned to the foot artillery batteries and "parks" (spare caissons, field forges, supply wagons, etc.); and one became a depot company for training recruits and remounts. Following the campaigns of 1800, the train was re-organised into eight battalions of six companies each. As Napoleon enlarged his artillery, additional battalions were created, rising to a total of fourteen in 1810. In 1809, 1812, and 1813 the first thirteen battalions were "doubled" to create 13 additional battalions. These 'double battalions' added the suffix 'bis' after their title, for instance, the doubled 1st became the 1st bis.[27] Additionally, after 1809 some battalions raised extra companies to handle the regimental guns attached to the infantry.[26] Following the Restoration, the train was reduced to just four squadrons of 15 x officers and 271 x men, raised to 8 x squadrons in 1815 during the Hundred Days.[27] The Imperial Guard had its own train, which expanded as La Garde's artillery park was increased, albeit organised as regiments rather than battalions. At their zenith, in 1813–14, the Old Guard artillery was supported by a 12-company regiment while the Young Guard had a 16-company regiment, one for each of their component artillery batteries.[28] Below is a list of the artillery train battalions:

Support servicesEngineersWhile the glory of battle went to the cavalry, infantry, and artillery, the army also included military engineers of various types. The bridge builders of the Grande Armée, the pontonniers, were an indispensable part of Napoleon's military machine. Their main contribution was helping the emperor to get his forces across water obstacles by erecting pontoon bridges. The skills of his pontonniers allowed Napoleon to outflank enemy positions by crossing rivers where the enemy least expected and, in the case of the great retreat from Moscow, saved the army from complete annihilation at the Berezina River. They may not have had the glory, but Napoleon clearly valued his pontonniers and had 14 companies commissioned into his armies, under the command of the brilliant engineer, General Jean Baptiste Eblé. His training, along with their specialized tools and equipment, enabled them to quickly build the various parts of the bridges, which could then be rapidly assembled and reused later. All the needed materials, tools, and parts were carried on their wagon trains. If they did not have a part or item, it could be quickly made using the mobile wagon-mounted forges of the pontonniers. A single company of pontonniers could construct a bridge of up to 80 pontoons (a span of some 120 to 150 metres long) in just under seven hours, an impressive feat even by today's standards. In addition to the pontonniers, there were companies of sappers, to deal with enemy fortifications. They were used far less often in their intended role than the pontonniers. However, since the emperor had learned in his early campaigns (such as the Siege of Acre) that it was better to bypass and isolate fixed fortifications, if possible, than to directly assault them, the sapper companies were usually put to other tasks. The different types of engineer companies were formed into battalions and regiments called Génie, which was originally a slang term for engineer. This name, which is still used today, was both a play on the word (jeu de mot) and a reference to their seemingly magical abilities to grant wishes and make things appear much like the mythical Genie. Under the Empire there were a number of notable changes in the engineer establishment. The six companies of miners were first reduced to five, then increased to nine, and in 1808 a 10th Company was formed and the whole corps divided into two battalions with each comprising file companies. The sapper battalions were increased in number once more until eventually there were eight (five French, one Dutch, one Italian, and one Spanish). But the losses in the Invasion of Russia led to the number being reduced to five battalions. An Imperial innovation was an engineer train battalion, which was badly needed, and in 1806 each sapper battalion was director to hold a park of tools. A number of pioneer companies were formed to provide unskilled labour for engineer work.[31] Sometime by the time of 1815, the battalions were grouped so that were at least three Engineer Regiments (Régiments du Génie) with at least two battalions each.[32] Battalions of sappers and miners constituted ‘magazines’ of men from which armies and corps drew companies, and sometimes only detachments, according to their needs. Engineers took a major part in sieges, they were responsible for road works in the field, they advised the infantry in the construction of field fortifications, they laid out the works for protecting gun emplacements, and they were entirely responsible for the fortification of fixed defences.[33] Below is a list of battalions within the engineer corps:

Medical ServiceThe most significant innovation was the establishment of a system of ambulances volantes (flying ambulances) in the closing years of the 18th century by Dominique Jean Larrey (who would later become Surgeon-General of the Imperial Guard). His inspiration was the use of fast horse artillery, or "flying artillery", which could manoeuver rapidly around the battlefield to provide urgent artillery support, or to escape an advancing enemy. The flying ambulance was designed to follow the advance guard and provide initial dressing of wounds (often under fire), while rapidly transporting the critically injured away from the battlefield. The personnel for a given ambulance team included a doctor, quartermaster, non-commissioned officer, a drummer boy (who carried the bandages), and 24 infantrymen as stretcher-bearers.[35] CommunicationsMost dispatches were conveyed as they had been for centuries, via messengers on horseback. Hussars, due to their bravery and riding skills, were often favoured for this task. Shorter-range tactical signals could be sent visually by flags or audibly by drums, bugles, trumpets, and other musical instruments. Thus, standard bearers and musicians, in addition to their symbolic, ceremonial, and morale functions, also played important communication roles. GendarmerieUnder Napoléon, the numbers and responsibilities of the gendarmerie—renamed gendarmerie impériale—were expanded significantly. In contrast to the mounted Maréchaussée, the gendarmerie were both horse and foot personnel; in 1800, these numbered approximately 10,500 of the former and 4,500 of the latter, respectively. In 1804 the first Inspector General of Gendarmerie was appointed and a general staff was established based out of the Rue du Faubourg-Saint-Honoré in Paris. Subsequently, special gendarmerie units were created within the Imperial Guard for combat duties in French-occupied Spain. Reserve ArmyNapoleon utilised the National Guard (Garde Nationale) on many instances, but was very reluctant to use them in the field, and instead kept them within the borders of France. During this period, the Reserves and National Guard were grouped into what became known as the 'Reserve Army', Armée de Reserve. This 'Army' was not a field army, but only an administrative group which oversaw all reserves throughout Metropolitan France. ReserveMost of the troops within the Reserve were retired troops or those who, for many reasons, wouldn't be able to deploy with the field armies. The Reserve was organised into two 'groups', the Legions which were regional forces composed solely of infantry, and the provisional regiments which were those of any other type. Below is a list of the units as they appeared by type: Cavalry The provisional cavalry regiments were formed in 1809, and consisted of the following:

These regiments however only lasted for a short time and were either absorbed into other regiments, or formed as new regiments. Infantry In 1803, four 'volunteer legions' were created of volunteers under the age of 40, with each legion comprising an artillery company.[36] In 1807, the new 'Departmental Legions' were formed by decree on 20 March 1807 for the defence of the borders, and based in the following towns: Lille, Metz, Rennes, Versailles, and Grenoble. Later that year, contrary to their initial purpose, the legions were sent into Spain becoming the 'Provisional Battalions'. The majority of these legions were destroyed at the Battle of Bailén, with small cadres of the first three battalions reformed on 1 January 1809, later becoming the 121st and 122nd Line Infantry Regiments. In 1809 and 1810, 30 demi-brigades were formed as provisional regiments, and were organised as follows:

A number of reserve legions (Légions de Reserve) were formed following these reorganisations:

During the Hundred Days, several auxiliary and regional units were formed, including the Chasseurs de La Vendée.[38] Along with the artillery, companies of veterans (Compagnies des Vétérans) were formed, with at least 16 of these being formed during this period comprising around 3 x Officers and 84 x Other ranks.[39] In addition, veteran fusilier companies (Compagnies des Fusiliers Vétérans) were formed, with at least 4 of the type being formed in the Jura region.[39] National Guard Throughout the Revolutionary Wars and early years of the consulate, the National Guard proved to be very good regional military police, and were able to be mobilised quickly in the event of invasion. Napoleon, therefore, saw the need in providing a constantly available force of National Guardsmen when needed. By the time of the War of the Fourth Coalition and subsequent invasion of Prussia, Napoléon ordered the mobilisation of 3,000 grenadiers and chasseurs of the national guard of Bordeaux to reinforce the coastal defences. Though the expected invasion never came, this small mobilisation proved the National Guard were ready, willing, and able to quickly provide defence where needed. A decree of 12 November 1806 ordered all Frenchmen aged 20 to 60 would be required to perform National Guard service. Under this decree, companies of Grenadiers and Chasseurs could, if possible, be called upon to perform domestic service in towns of more than 5,000 inhabitants alongside the Gendarmerie, or mobilise for military service. Following the failed Walcheren Campaign, Napoleon's commitment to the National Guard was expanded, and by the end of the year released all regulars into the field while leaving border protection duties and coastal defences solely to the National Guard. On 14 March 1812, a decree called for the recruitment of 88 cohorts (battalion strength), recruited by their respective departments in proportion to the population.[40][41] These new cohorts were charged specifically with strengthening the coastal troops and border surveillance corps.[42] These cohorts each had an artillery company attached.[43] Under the 1813 reorganisations, the cohorts were absorbed by the regular army into 22 new line infantry regiments. The 88 companies of artillery were incorporated into the regular artillery at this same time as well. When the Invasion of France began in 1813, a decree was signed to call for 101,640 more men to be raised from the National Guard for the protection of the country. Two divisions were present at the Battle of Fère-Champenoise and at the Battle of Paris. Most regional national guards consisted of a cavalry unit (usually light cavalry (Chasseurs à Cheval)), 1 or 2 line infantry battalions, and sometimes a regional artillery/coastal artillery company. The National Guard of Paris for example had 12 Legions (companies), and comprised infantry and Tirailleurs.[44] During the Hundred Days, a company of artillery part of the National Guard formed part of the Belfort garrison.[39] During the Hundred Days, new National Guard divisions were formed with many being integral parts of the Corps of Observations. At the Battle of Vélizy and Battle of Rocquencourt, National Guardsmen were able to hold up a large Prussian column advancing in the East of France. In retaliation, the Prussians burned the town of Vélizy. During the Hundred Days, the National Guard divisions were spread as follows:

Coastal ArtilleryNapoleon had inherited 100 x companies of coastal artillery (Cononniers Gardes du Côtes) who manned shore defences, totalling 10,000 men. However, after Napoleon's 1803-1805 reforms, the artillery was completely reorganised into 100 x mobile companies under artillery command and 28 x static companies of National Guard, each company with a nominal establishment of 121 (actual strength varied). By 1812, some 144 x companies existed, but all were disbanded in May 1814 following the restoration.[23] The coastal artillery's uniform was a black bicorne with a green pompom, a light blue coat with blue cuffs, white turnbacks, sea green collar, lapels, cuff flaps, waistcoat, and breeches, red epaulettes, and yellow buttons. They used infantry equipment, the cartridge box bore a brass badge of an anchor superimposed on a crossed cannon barrel and musket, and the sword knot was red. After the shako was adopted in 1806, it was black with brass chinscales latterly with a red tufted pompom, and a plate bearing crossed cannon, anchor and branches of oak and laurel. From 1812 the plate was like that of the foot artillery please crossed cannons and an anchor.[23] Garrison ArtilleryThe 28 x companies of garrison artillery (Canonniers Sédentaires), raised to 30 x companies by 1812 wore foot artillery uniforms, with a shako plat without a number. Most distinguished was the Garrison Artillery of Lille, a unit formed in 1483, which merged with the National Guard in 1791, and performed with distinction in the Siege of Lille.[23] Their shake plates bore their title. An illustration of a musician of 1815 shows an ordinary uniform but pointed scarlet cuffs, gold trefoil epaulettes, and a cylindrical shako bearing a large brass plate of a trophy of arms atop an 1812-patter shield bearing a grenade over a crossed cannons, with a plume of red over white and blue, over a blue ball.[23] The garrison artillery were not exclusively garrison troops, for example, the Lille Corps (formed into a battalion of two companies in 1803) served in the Walcheren Campaign, where they lost 3 x officers and 24 x other ranks.[23] Veteran ArtilleryIn April 1792, the previous Invalid Companies were replaced by the Veteran Companies, of which 12 x were artillery, raising to 13 x companies of 52 x men in September 1799. In May 1805, the artillery was enlarged to 25 x companies of 100 men each, 19 x companies in 1812, and reduced back to 10 x companies in May 1814. The uniform was that of the foot artillery.[23] OrganisationCorps of ObservationA Corps of Observation (French: Corps d'Observation) was a field formation commanded by a senior officer, with the rank of Brigade General, Divisional General, or at largest a Marshal of France. These formations were separate and independent units which didn't report to an overall army. These corps were designed to advance, to occupy, and hold strategic barrages blocking probable enemy lines of approach.[47]

Military DistrictsMilitary Divisions (really districts) were originally formed following the Seven Years' War to oversee the recruitment of the province, control the regional militia and later militia grenadiers, and local garrisons. In 1812 they were reorganised and expanded into the following districts along with their departments and HQ location:[48]

Corps

ListsList of regiments:

Formations and tactics While Napoleon is best known as a master strategist and charismatic presence on the battlefield, he was also a tactical innovator. He combined classic formations and tactics that had been used for thousands of years with more recent ones, such as Frederick the Great's "Oblique Order" (best illustrated at the Battle of Leuthen) and the "mob tactics" of the early Levée en masse armies of the Revolution. Napoleonic tactics and formations were highly fluid and flexible. In contrast, many of the Grande Armée's opponents were still wedded to a rigid system of "Linear" (or Line) tactics and formations, in which masses of infantry would simply line up and exchange volleys of fire, in an attempt to either blow the enemy from the field or outflank them. Due to the vulnerabilities of the line formations to flanking attacks, it was considered the highest form of military manoeuvre to outflank one's adversary. Armies would often retreat or even surrender if this was accomplished. Consequently, commanders who adhered to this system would place a great emphasis on flank security, often at the expense of a strong centre or reserve. Napoleon would frequently take full advantage of this linear mentality by feigning flank attacks or offering the enemy his own flank as "bait" (best illustrated at the Battle of Austerlitz and also later at Lützen), then throw his main effort against their centre, split their lines, and roll up their flanks. He always kept a strong reserve as well, mainly in the form of his Imperial Guard, which could deliver a "knockout blow" if the battle was going well or turn the tide if it was not. Some of the more famous, widely used, effective, and interesting formations and tactics included:

Ranks of the Imperial ArmyUnlike the armies of the Ancien Régime and other monarchies, advancement in the Grande Armée was based on proven ability rather than social class or wealth. Napoleon wanted his army to be a meritocracy, where every soldier, no matter how humble of birth, could rise rapidly to the highest levels of command, much as he had done (provided, of course, they did not rise too high or too fast).[citation needed] This was equally applied to the French and foreign officers, and no less than 140 foreigners attained the rank of Général.[49] By and large this goal was achieved. Given the right opportunities to prove themselves, capable men could rise to the top within a few years, whereas in other armies it usually required decades if at all. It was said that even the lowliest private carried a marshal's baton in his knapsack. Maréchal d'Empire, or Marshal of the Empire, was not a rank within the Grande Armée, but a personal title granted to distinguished divisional generals, along with higher pay and privileges. The same applied to the corps commanders (General de Corps d'armee) and army commanders (General en chef). The highest permanent rank in the Grande Armée was actually Général de division and those higher than it were positions of the same rank but with separate insignia for appointment holders.[50] The position of Colonel General of a branch (such as dragoons or grenadiers of the Guard) was akin to Chief Inspector-General of that branch, whose office holder used his current officer rank and its corresponding insignia.

See also

Footnotes

References

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||