|

Fiction theory Fiction theory (also referred to as Fictionality theory) is a discipline that applies a form of possible world theory to literature. Drawing on concepts found in related theories and psychological ideas such as parasocial interaction (PSI) and fictionalism, theorists of fiction study the relationships between perceived textual worlds and reality outside the text. Thus, the primary principle of fiction theory is that the relationships between the speculative nature of fiction and the actual world in which we live are complicated. This further suggests that perceived truths born out of fiction worlds develop a sense of coherency in which they maintain a sense of realism.[1] As a result, this theory offers alternate ways of exploring and asking questions about relations between the fictitious and the actual world. Fundamentals of fiction theoryFiction theory acts simultaneously in fields of both literary analysis and psychology. It suggests that the perception of the actual, such as the world around us, is formulated on individual understanding. Further, fiction theory functions on the extension of this perception to the non-factual, wherein the understanding of the make-believe can translate to the factual.[2] Such is the reason that literature may be understood as a text that is self-consciously artistic and relatable, rather than solely a medium through which to convey information, like a newspaper article. Fiction theory is typically recognized through parasocial interactions between readers and fictional characters. Most often these connections are formulated through self-identification, wherein people empathize and/or identify with the object of fiction.[3] Oftentimes these connections present themselves in an individual's sense of friendship, or romantic attraction with the fictional. This also can appear as literal self-identification in which the reader feels as though the character reflects their traits. There has been heavy criticism of this aspect of the theory, as there is disagreement regarding whether this self-identification is a delusion. Fiction theory has garnered some popularity as TikTok continues to have millions join the #BookTok movement which often highlights relationships between the real and the fictive.[4] Psychology of the actual and the fictiveFathali M. Moghaddam leads the discussion about fictional and psychological interaction, claiming that novels have a bearing on psychological discussions and discourse, thus they should be incorporated into wider topics of the mind.[5] With that, he separates this interaction into three distinct levels at which these disciplines coincide.[6]

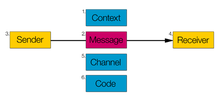

The understanding of fiction theory lies within the third principle which relies on the schema of the individual to mentally conceptualize the story in which they are attempting to understand.[1] This process subconsciously weaves reality into fiction, wherein the awareness of the consumed content becomes something not entirely fictional, nor factually true. Furthermore, this schema is responsible for the prediction of story and character arcs, as our understandings of human behaviors guide our literary comprehension. The story world model is a commonly used method of explaining fiction theory.[1] In short, this model relies on reader logic that certain things can choose to be inconsequential or simply not exist in a story opposite of reality. For example, the presence of technology. However, despite accepting some narrative truths this model too, relies on the reasoning that the fictional (on some level) functions like that of the real. In theory, identifying the story's logic allows readers to move quickly and with a heightened understanding that would otherwise make literary comprehension laborious.[1] Related theories & applicationsRoman Jakobson and linguistics  Roman Jakobson was one of the most celebrated linguists of the early-to-mid twentieth century, developing the system of structural linguistics. Further, he developed linguistic systems that perpetuated the discussion of viewing art as a mode of communication that is intentionally aesthetic. Jakobson then further applied linguistics to analyses of literary texts. In his communication model, Jakobson divides a communicative act between an addressor and addressee into parts functioning independently of one another: message, code, context, and contact.[7] According to Jakobson's model, art is created when the message itself (which carries the poetic function) is stressed. This model functions in conjunction with Roland Barthes who designed a system of five major codes (S/Z) that function as tools to analyze narrative texts in ways that move beyond examinations of plot and structure. Resulting in the transference of text into a fully developed narrative that has effects beyond the literal.[8] Both offer a way to explore the nature of a literary work through the application of semiotics generating responses outside the text. StructuralismStructuralism, founded and pioneered by both Ferdinand de Saussure and Jakobson, is a system of semiotics by which we can identify the underlying significance of linguistic practices.[9][10] Saussure's earliest models of this are rooted in the "systemic, relational, arbitrary [and] social" principals of language, wherein the formal purpose is intended to be underscored in favor of the wider purpose that it serves.[9] The purpose of linguistic structuralism was to understand the underlying structures that dictate all forms of language, whether they appear in narrative, prose, script, or screenwriting. By identifying these structures, philosophers sought to reveal the common principles that make different linguistic forms coherent and meaningful.[10] Thus, the idea of structuralism relates to fiction theory by providing tools to analyze the underlying structures that shape narratives. It shifts the focus from content to conventions that produce meaning, offering a systematic and rational approach to understanding how fiction works. Bakhtin and the DialogicMikhail M. Bakhtin is known for his theories of the self through dialogue, which asserts that knowledge and experience are gained through interaction with the surrounding world.[2][11] Bakhtin, in his career, emphasized the effect of linguistic environment (through literature and the actual) on the perception of the individual. He also noted that internal dialogue and reflection are a part of this system and evidentiary of the self-sufficient thought process that linguistic interaction creates.[2] Bakhtin famously criticized Fyodor Dostoevsky for generating characters within his literary works that lacked authentic interactions, thus maintaining "artificial" creations.[12] He accredited this to an inundation of authorial interjection, which made the reading difficult for audiences to connect with as they could not relate with the experiences and perceptions of the fictional.[2] Kermode to DoleželFrank Kermode, author of The Sense of an Ending: Studies in the Theory of Fiction, was among the first to argue the importance of literary works in a multidisciplinary sense, more specifically the impact that they have on the human perception of time.[13] Kermode emphasizes the endmost interpretation of existence as derived from humans' constant yearning for an ultimate end which, in turn, has affected storytelling over the centuries. In his book, he distinguishes between fiction and myth, posing the latter as something exploitative while fiction is meant to connect with reality meaningfully.[13] Fiction consists of stories all individuals create about their lives to keep on living in a world that makes few guarantees and is full of inexplicable phenomena. This is built upon by Lubomír Doležel, author of Heterocosmica: Fiction and Possible Worlds, who addresses possible world theory, positing that works of fiction are one of the many ways that humans can consider the theoretical world that could have been.[14] Doležel explains the internalized logic of the fictive, giving bearing to the world and characters within. He then shifts into an ontological and epistemological approach wherein he relates these works of fiction to reality, and how storytelling can further impact our perception of narrative understanding.[14] Alternate viewsActualism Saul Kripke, a leading analytic philosopher, frames actualism as something that acknowledges the existence of the possible while maintaining its autonomy from that of the actual world.[15] Kripke employs possible word theory to further assert that we utilize the possibilia, possible things, to conceptualize the concrete, but that does not prove the position of the fictional within the actual.[15] Actualism also contends that identifying and judging things through the possible is "methodologically" the starting part of all human conceptualization.[15] Actualism, in Kripke's context, is the direct refusal of possibilism which resembles fiction theory in its acceptance of the non-concrete. Peter F. Alward, a Canadian professor of philosophy, criticizes "anti-realist" views of fiction attributing the success of such theories to fictional creationism.[16] Fictional creationism is the principle that the entities of the possible should be regarded as realistic creations because of they bear on the reader or observer.[16] Alward further asserts that the reference to the non-real or the possible is not to be considered real, or having any bearing in reality. He describes this process as an innate understanding that humans have about distinguishing what is literally had (and thus tangible) or what type of qualities one could potentially possess.[16] Separation of purposeThomas Pavel, a literary critic, argues that the fictional world deserves to be examined on its terms rather than as a vehicle for the real. His thesis in Fictional Worlds is a critique of structuralism by its insistence on the idea that narrativity limits the possibility of imitating reality.[17] Pavel differs from fellow fiction theorists because he separates literature from its referential relationship to the actual world. He asserts that fictional worlds instead demand tremendous respect for their ability to serve as powerful tools of knowledge for studies within literary disciplines.[17] Further reading

References

|