|

Feminist poetry

Feminist poetry is inspired by, promotes, or elaborates on feminist principles and ideas.[1] It might be written with the conscious aim of expressing feminist principles, although sometimes it is identified as feminist by critics in a later era.[1] Some writers are thought to express feminist ideas even if the writer was not an active member of the political movement during their era.[1] Many feminist movements, however, have embraced poetry as a vehicle for communicating with public audiences through anthologies, poetry collections, and public readings.[1] Formally, feminist poetry often seeks to challenge assumptions about language and meaning.[2] It usually foregrounds women's experiences as valid and worthy of attention, and it also highlights the lived experiences of minorities and other less privileged subjects.[2] Sometimes feminist poems seek to embody specific women's experiences, and they are often intersectional registering specific forms of oppression depending on identities related to race, sexuality, gender presentation, disability, or immigration status.[2] This has led to feminist writing journals like So To Speak providing a statement of intention to publish the work of women and nonbinary people in particular. Kim Whitehead states that feminist poetry has "no identifiable birth date," but there are a few key figures identified as early proponents of feminist ideas, and who convey their politics through poetry.[2] The title of first feminist poet is often given to Sappho, at least in part because she seems to write about female homosexuality in Ancient Greece, a culture and time when lesbian sexuality was usually ignored or erased.[3][4][5] Feminist Poetry in Asia Feminist Aspects of Sanskrit WritingThe beginning of works categorised as literature in India began with the Sanskrit term kāvya, a discourse separate from science or from the purely oral, and specific literary style that included works thought to contain a kind of soulfulness.[6] In this early period, men were often posed as poets, and women as a kind of muse, as in the tenth century explanation for the origins of Indian literary culture: Poem Man's wife ("Poetics") chases him across South Asia creating varying kinds of literature across the region.[6] Poetry was certainly an important part of political cultural life in the Sanskrit cosmopolis, and some women contributed; for example the poet Rajasekhara tells of women in different regions who entertain with songs.[6] The early civilisation of Khmer country in modern-day Cambodia cultivated a literature in Sanskrit, and diverged from its neighbours in creating a strain of poetry from the fifth century to the thirteenth century in which women were a source of praise and admiration.[6] Take for example the Mebon Inscription of Rājendravarman, which features eulogies for specific women of note, and which is, according to Sheldon I. Pollock, "without obvious parallel in South Asia," and may be related to "specific kinship structures in the region."[6] Nineteenth Century Feminist Poets in IndiaEarly anglophone women poets in India blended native traditions and literary models from Europe.[7] Amongst these early feminists, the Dutt Sisters - Toru Dutt (1856–1877) and Aru Dutt (1854–1874) stand out, and are sometimes compared to the Brontë Sisters in England.[7] The Dutt sisters came from a family of poets, including their father Govind Chandra Dutt, and their access to education was unprecedented.[7] The mother of the family Kshetramoni Mitter Dutt along with all three children - Toru, Aru, and their brother Abju Dutt, had received an education in English, and to some extent, in the Bengali language.[7] The family had a reformist bent, and some members had converted to Christianity.[7] Both sisters visited England in the 1870s, and attended the higher lectures for women at Cambridge University. Toru Dutt's poetry in particular has been labelled extraordinary, because her writing "created a new idiom in Indian English verse."[7] Spanning the turn from the nineteenth to twentieth century, Sarojini Naidu (1879–1949) represents a figure for whom politics and poetry are intertwined.[7] Like the Dutt Sisters, Naidu was allowed access to all the educational resources she desired, and she passed the Madras University matriculation examination at age 12. She came from a large and free-thinking family.[7] Her father, Aghorenath Chattopadhyay, was a well-regarded doctor, known for his educational reforms, and her mother, Barada Sundari Devi, was educated at a Brahmo school.[7] Naidu had seven siblings all of whom made contribution to Indian life, for example her brother Virendranath Chattopadhyay was an Indian revolutionary.[7] Naidu studied at Girton College, Cambridge, which brought her into contact with writers of the day, including Arthur Symons, and W.B. Yeats.[7] Ultimately, Naidu's unconventional upbringing and education were catalysts for her intellectual powers, since as she writes in her roman à clef 'Sulani,' ""Unlike the girls of her own nation, she had been brought up in an atmosphere of large un-convention and culture and absolute freedom of thought and action."[8] After her marriage to Govindarajulu Naidu - controversial because of his age and class - Naidu began publishing poetry to international acclaim, and in parallel with this literary art, she maintained her nationalist efforts, eventually becoming the first Indian woman to serve as president of the Indian National Congress.[7] Post 1960s Feminist PoetryAnthologies were an important part of foregrounding women's writing in volumes like Eunice De Souza's Nine Indian Women Poets (1997).[9] Feminist Poetry in Central America and the Caribbean The Feminist Legacy of Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz During the Latin American colonial period, Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz (est 1651–1695) was a poet, dramatist, and nun.[10] Exceptionally talented and intelligent, Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz chose to spend most of her life in the Convent of the Order of St. Jérôme, and her response to a critical Bishop, Respuesta a Sor Filotea, is hailed as one of the first feminist manifestos.[10] Not only did Sor Juana have to deal with the criticisms of men of her era, but she also faced the Spanish perception of literature from the colonies as second-rate.[11] Sor Juana's poems challenge the assumptions of men about women, for example in 'You Foolish Men.'

The fact that she chooses to avoid a heteronormative life with marriage and children is often held up as a feminist choice, and she represents the possibility to be a woman who 'pursues knowledge and procreates only through art and not through a genetic legacy.'[13] Post 1960s Feminist Poetry in Central America and the CaribbeanAnthologies of women's writing in the 1980s foregrounded the importance of women poets in the Caribbean, for example in M.J. Fenwick's Sisters of Caliban (1996) described as "a gendered and racialized position of resistance".[14] Feminist Poetry in North America Early Feminist Poets in North AmericaThough they lived in an era before an organised feminist movement, certain American poets have been lauded by feminist literary criticism as early examples of feminist writers. Feminist poetry in the United States is often thought of as beginning with Anne Bradstreet (1612–1672), the first poet of the New World. There were also, however, native poetic traditions before colonialism, which continue to the present day, and represent an important strand of American poetry. Native traditional verse has included "lyrics, chants, anecdotes, incantations, riddles, proverbs, and legends."[15] While it is difficult to ascertain from these oral traditions whether the authors of early texts were male or female, precolonial native poetry certainly addresses issues relevant to women in a sensitive and positive way, for example the Seminole poem, 'Song for Bringing a Child Into the World.'[16] In fact, native poetry is a separate but relevant tradition in the United States; as poet Joy Harjo comments, "The literature of the aboriginal people of North America defines America. It is not exotic."[17] In the context of Canada, Anne Marie Dalton argues that at least some indigenous communities in North America (though not all) have lived by practicing ecofeminism with regard to women's roles, and the sustainability of the land.[18] When colonialism did arrive, Anne Bradstreet was one of the first poets to win acclaim, and many of her poems are thought to have feminist themes.[19][20][21] The mother of eight children, Bradstreet sometimes found herself in conflict with her domestic circumstances and her role as a Puritan woman.[19] Feminist literary criticism defined Bradstreet in retrospect as a "protofeminist," because of her "gender awareness," and her treatment of domestic concerns of importance in women's lives.[20] Poet Alicia Ostriker describes Bradstreet's style as "a combination of rebellion and submission," a pattern that Ostriker also sees in poets to come like Phyllis Wheatley and Emily Dickinson.[21] Phyllis Wheatley (1753–1784) was brought to the United States from Africa as a slave, and sold to the Wheatley family of Boston in 1771.[22] A prodigy as a child, Wheatley was the first black person to publish a book of poems in the American colony, and though her poems are sometimes thought of as expressing "meek submission," she is also what Camille Dungy describes as "a foremother," and a role model for black women poets as "part of the fabric" of American poetry.[21] Involved in the abolitionist movement, Wheatley became "a spokeswoman for the cause of American independence and the abolition of slavery."[23] Nineteenth century poet Emily Dickinson (1830–1886) is often thought of as feminist, though she never wrote for public audiences. Not necessarily recognized in her own lifetime, Dickinson offers powerful female speakers. Engaging with male writers like Ralph Waldo Emerson or William Wordsworth, her work is praised for developing "others ways of representing the position of a female speaking subject" in particular romantic and psychological dynamics.[24] See for example the declaration of desire and longing in 'Wild nights - Wild nights!.'[21] In the 1970s, feminist literary criticism articulated Dickinson's feminism through groundbreaking studies by Margaret Homans, Sandra Gilbert and Susan Gubar, and Suzanne Juhasz. Critics point in particular to Dickinson's expression of anger at women's confinement, to her re-gendering of external and internal realities, to her use of feminist motifs, and to her articulation of her particular position in Puritan, patriarchal culture.[25] Dickinson also proves that confinement to domestic life does not dictate an inability to create great poetry.[26] As the poet Adrienne Rich writes, "Probably no poet ever lived so much and so purposefully in one house; even, in one room."[26] Post 1900s North American Feminist Poets Feminist poets of the early twentieth century harnessed the new opportunities and rights which came as a result of coeducational resources now afforded to women.[27] Cristianne Miller goes so far as to say that 'In no period before and rarely since have women poets had greater success and influence than in the first half of the twentieth century in the United States.'[27] Living through the turn of the century was Alice Moore Dunbar-Nelson(1875–1935), a poet often thought of in relation to her marriage to Paul Dunbar.[21][28] Dunbar-Nelson, however, is an accomplished writer in her own right, praised by poet Camille Dungy for breaking out of writing only about "black women's things," instead addressing "the theater and war of life."[21] Born in New Orleans, Dubar-Nelson's family had a heritage of African American, Anglo, Native American, and Creole roots.[28] Camille Dungy suggests that bringing black women writers like Dunbar-Nelson into the feminist canon alongside Bradstreet and Dickinson is of great importance in rediscovering literary foremothers for black women writers.[21] The early twentieth century was also a significant moment for feminism, because it saw the rise of the suffragist movement, and poets responded to the political moment by writing poems regarding the debate as to whether or not women should have the right to vote. In her collection Suffrage Songs and Verses, Charlotte Perkins Gilman criticises wealthy women, who because they live a life of ease, deny other women their rights.[29] Alice Duer Miller (1874–1942) wrote poems mocking anti-suffragist advocates, which were published in the New York Tribune, a popular news outlet of the era.[30][31][32] While some poets have been embraced by the feminist canon, others are seen as awkward additions in spite of their success, for example Gertrude Stein (1874–1946) is often defined more as a poet involved in modernist experimentation than feminist discourse.[21][33] Some of modernism's tenets seem incompatible with some kinds of feminism, like the repression of emotion, and avoidance of domesticity.[21] Nevertheless, second wave feminists found modernist women poets like H.D. (1886–1961) to be a powerful example, unfairly overlooked by male critics.[21][34] By the time of the 1940s, magazines were being set up which, though perhaps not obviously feminist, certainly in their practices were very different to male-run publications: take for example Contemporary Verse (1941–52) published in Canada by a group of women writers, including Dorothy Livesay, P.K. Page, and Anne Marriott.[35] Post 1960 North American Feminist Poets Historian Ruth Rosen describes the mainstream poetry world before 1960 as "an all boy's club," adding that poetry was not "women's place," and explains that in order to get a poetry book published, writers would have to overcome their gender and race.[36] The interest of American feminist poets in the rights of minorities have often put them in conflict with American institutions like the American Academy of Poets.[2] One of the strategies of feminist poets is to demonstrate "their opposition to a dominant poetry culture that does not recognize the primacy of gender and other oppressions".[2] 1960s feminist poetry provided a useful space for second wave American feminist politics.[37] The poets, however, were not necessarily unified in their themes or formal techniques, but had links to specific movements and trends, such as the New York Poets, the Black Mountain poets, the San Francisco Renaissance, or the Beat Poets.[2] Denise Levertov (1923–1997), for example, refined and built upon poetics from the Black Mountain School.[38][39] Women like Sylvia Plath (1932–1963) and Anne Sexton (1928–1974) provided a feminist version of the Confessional Poets' poetics, which worked alongside feminist texts of the day, like Betty Friedan's The Feminine Mystique, to "address taboo subjects and social limitations that plagued American women" (although Plath died before The Feminine Mystique was published)[40][36][41][42] Lucille Clifton (1936–2010) also borrowed from Confessional poetics, a strategy that was key according to Adrienne Rich for avoiding being trapped between "misogynist black male critics and white feminists still struggling to unearth a white woman's tradition."[43][44] Confessionalism lent to feminist poetry the possibility of agency for the female speaker, and the refusal to present well-behaved women, though it was troubling that the Confessional women poets who committed suicide tended to be foregrounded and promoted in poetry circles.[36] Muriel Rukeyser (1913–1980) was a generation older than Plath and Sexton, and rejected the suicidal poetics of the Confessional writers.[36] Rukeyser also wrote frankly about the body and sexuality, inspiring later poets like Sharon Olds.[45] In addition, Rukeyser's leftist politics and militant writing style proved to be a model for poet Adrienne Rich.[36] Both poets also contributed to the anti-Vietnam War movement: for example Rukeyser and Rich took part in readings as part of the event series, the Week of the Angry Arts Against the War in Vietnam.[2] Adrienne Rich (1929–2012) also became a key feminist poet, praised by Alicia Ostriker for bringing "intellect" to poetry, "something that women were not supposed to have," as well as "a leftward leaning sensibility in which coming out as lesbian was just one part."[36][46] Rich's "Diving into the Wreck" is an important feminist poem, as it describes moving down as an act of triumph, where the wreck might be history, literature, or human life, and the poem itself is a kind of "battlecry."[36] Famously, when Rich received the National Book Award for her collection, Diving into the Wreck, she accepted it on behalf of all the female nominees, including Audre Lorde and Alice Walker:

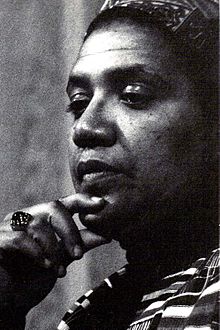

Audre Lorde (1934–1992) was a feminist poet whose poetry and prose writings have had a great impact on feminist thinking to the present day.[48][49][50] Sometimes thought of as a writer who developed a "black lesbian eroticism," Lorde's poetry also shows a deep ethical and moral commitment, which seeks to challenge racism, sexism, and homophobia.[51] Many of Lorde's poems have a great deal in common with the modern-day campaign #blacklivesmatter, as they pose questions about institutionalised racism in American public services like the price force, for example in her poem 'Power':

Lorde's work has also proved to be an inspiration to feminists working on the subject of feminist killjoys, and the trope of the angry black woman, often used as an excuse to belittle or reduce the impact of just concerns about racism.[53] Lorde's poems often draw attention to the universalising tendencies of some white feminisms, so in a poem about a mythical woman, 'A Woman Speaks,' only at the end does Lorde draw attention to the problematic universal, white woman, adding

Lorde went on to be an effective and challenging teacher of other women poets, such as Donna Masini.[45] Feminist Anthologies in North America in the 1970s and 80sIn the 1970s and 80s, feminist poetry evolved alongside the feminist movement, becoming a useful tool for activist groups organised around radical feminism, socialist feminism, and lesbian feminism.[2] Poetry readings became spaces for feminists to come together in cities and in rural communities, and talk about sexuality, women's roles, and the possibilities beyond heteronormative life.[55] Figures like Judy Grahn were figureheads for the women's movement, providing electrifying readings that enlivened and inspired audiences.[55] Often the poems were political, and sometimes the writers tried to use language that "ordinary women" could read and understand.[2] Countering tokenism was also an important aspect of the feminist poetry project.[55] Carolyn Forché describes the "blue velvet chair" effect, inspired by group portraits of canonical poets, in which one - but only one - woman writer was allowed to join the men, often sat in a Victorian blue velvet chair.[55] As poetry took on a new significance for the feminist movement, so a number of new poetry anthologies were published which emphasised women's voices and experiences.[37][56] Anthologies played an important role generally in opening up the political consciousness of poetry, an important example being Raymond Souster's volume, New Wave Canada: The Explosion in Canadian Poetry (1966).[35]Louis Dudek and Michael Gnarowski describe the anthology's embracing of counterculture, including new ideas about sexuality and the role of women.[35] Other anthologies began to focus specifically on women's writing, such as:

Other anthologies created new canons of women's writing from the past, such as Black sister: poetry by black American women, 1746-1980 (1981) edited by Erlene Stetson; or Writing Red: An Anthology of American Women Writers, 1930-1940 (1987) edited by Paula Rabinowitz and Charlotte Nekola. Such anthologies "established solid ground for the communication and circulation of feminist ideas" in the American and Canadian Academies.[56] Conferences also provided important spaces for feminists to share and discuss ideas about the possibilities of poetry: for example a key moment for Canadian feminist poetry was the "Women and words / Les femmes et les motes" conference in 1983.[57][56] The Vancouver convention brought together women writers, publishers, and booksellers to discuss the issues of the Canadian literary world, including gender inequity.[57][56] Modern Feminist Poetry in North AmericaOne change in the writing of women poets after the 1960s and 1970s was the possibility of writing about women's lives and experiences.[45] To give authority to women's voices, writers like Honor Moore and Judy Graun held workshops specifically for women in order to overcome women's inner critics exacerbated by sexism.[45] These networks of mentorship sprang up in feminist communities, and in universities.[45] The work at this time was focussing on "images of women," and this often meant broadening representations.[58] This methodology eventually began to be criticised, however, because it failed to recognise the complications of violence embedded in the very structure of language.[59] Writers influenced by the avant-garde and by L=A=N=G=U=A=G=E poetry sought to challenge the idea of language's neutrality.[59] US feminist language poets like Lynn Hejinian or Susan Howe, or Canadian writers like Daphne Marlatt looked back to the legacy of experimentalist modernists like Gertrude Stein, or Mina Loy, and also to diverse sources of inspiration like Denise Levertov, Marguerite Duras, Virginia Woolf, Nicole Brossard, Phyllis Webb, Louky Bersianik, and Julia Kristeva.[59] They also reframed the language poetics from male mentors like Charles Olson, Robert Creeley, Gary Snyder, or Allen Ginsberg.[59] Poets also sought to intervene in spheres traditionally dominated by men. Take for example Eileen Myles' intervention into politics in her 1992 "Write-in Campaign for President."[60][45] By the time of the 1990s, and the rise of intersectionality as a key feminist term, many feminist poets resisted the term "woman poet," because it suggested "too confining a collective identity."[2] They also sought to undermine "the assumption that has sometimes structured feminist political organizing and even feminist literary publishing and criticism—that gender can be separated from race, ethnicity, class, and sexuality, and that white middleclass women first and foremost have the tools and the knowhow for the enterprise of analyzing gendered experience and literary production."[2] Present day feminist poetry in North America holds space for a great variety of poets tackling identity, sexuality, and gender issues. Key writings in the recent past include Claudia Rankine's careful skewering of race related microaggressions in Citizen,[61] Dorothea Laskey's "ferocious confession" in Rome for example,[62] and Bhanu Kapil's challenge the violent inherent in structures of language and institutions.[63] Feminist Poetry in Western Europe Feminist Writing after Mary WollstonecraftEighteenth century advocate for women's rights Mary Wollstonecraft (1797–1851), put great emphasis on the power of the poetic imagination as a liberator tool, and many nineteenth century British women writers were inspired by Wollstonecraft to use poetry to enter public debates about gender roles, poverty, and slavery.[64][65] The verse-novel Aurora Leigh (1856) by Elizabeth Barrett Browning (1806–1861) is one such feminist work, which challenged a prevailing attitude that women's lives were incompatible with writing poetry.[1][66] Aurora Leigh had a very public impact, for example influencing the views of American social reformer Susan B. Anthony regarding the traditional roles of women, especially in relation to the tension between marriage and women's individuality.[67] Late Nineteenth Century Feminist Poets in BritainOften cited as an early feminist poet, Amy Levy (1861–1889) is described by writer Elaine Feinstein as the first modern Jewish woman poet.[68][69][70] At the age of 13, Levy published her first poem in the feminist journal, the Pelican, and she grew to maturity surrounded by writers and social reformers on the London scene of the era, such as Eleanor Marx and Olive Schreiber.[68] Though nothing is known for sure about Levy's sexual relationships, she is often thought of as a lesbian poet, though some critics have challenged affixing a sexual category to Levy.[71] Levy's poems, however, are an early example of poetry that challenges heteronormative roles.[72][73] Twentieth Century Feminist Poets in BritainLevy is often thought of as prefiguring or representing an early version of the New Woman, a stereotypical image of an independent woman who often worked rather than relying on her menfolk, and was associated with gender bending and deviance.[74][75] Historically, the end of the nineteenth and beginning of the twentieth century was an era of surplus women, who had to work to survive: by 1911, 77 per cent of women workers in the UK were single.[76] Alongside the struggle of suffragettes campaigning for votes for women, many British feminist poets sought to emulate the example of Victorian women writers, often expressing their radical political beliefs through poetry.[77] Often the writers were not professional poets, but wrote out of necessity, including satirical portraits of politicians, or writings from prison, as in Holloway Jingles, a collection of writing from imprisoned women collated by the Glasgow Branch of the Women's Social and Political Union.[78] British Feminist Poets and ModernismIn the inter-war years, British women poets associated with modernism began to find themselves public figures, though their feminist ideas sometimes came into conflict with the literary establishment which remained a kind of "exclusive male club."[79] Often these writers are difficult to categorize in relation to literary groups traditionally used, like the avant-garde or modernists.[79] This was also a period when American women poets living in Britain made an important contribution to the writing of the day: writers like H.D., Mina Loy, and Amy Lowell all combined radical poetic content with experimentation of form, allowing them to explore feminist polemic and non-heteronormative sexualities in innovative new modes.[79] Other British feminist poets of the time like Anna Wickham, Charlotte Mew, and Sylvia Townsend Warner, receive less critical attention, but also sought to challenge and reevaluate tropes of femininity.[79] Post 1960s Feminist Poetry in BritainDuring the 1960s, the Women's Liberation Movement in the UK had a great influence on the literary world.[80] Feminist publishers, Virago (founded in 1973), Onlywomen (1974), The Women's Press (1978), and Sheba (1980), were established, alongside magazines like Spare Rib.[80] Like their counterparts in the US, British feminist editors in the 1970s and 80s created landmark anthologies of women's poetry, which foregrounded the variety and strength of women's writing.[80] These included Lilian Mohin's One Foot on the Mountain (1979), Jeni Couzyn's The Bloodaxe Book of Contemporary Women Poets (1985), Moira Ferguson's First Feminists: British Women Writers 1578-1799 (1985), Kate Armstrong's Fresh Oceans (1989), Jude Brigley's Exchanges (1990), and Catherine Kerrigan's An Anthology of Scottish Women Poets (1991). See alsoReferences

|