|

Early 2000s recession

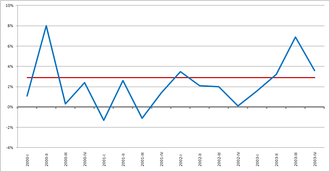

30 year minus 3 month 10 year minus 2 year 10 year minus 3 month 10 year minus Federal funds rate The early 2000s recession was a major decline in economic activity which mainly occurred in developed countries. The recession affected the European Union during 2000 and 2001 and the United States from March to November 2001.[1] The UK, Canada and Australia avoided the recession, while Russia, a nation that did not experience prosperity during the 1990s, began to recover from it.[citation needed] Japan's 1990s recession continued. A combination of the Dot Com Bubble collapse and the September 11th attacks lengthed and worsened the recession. This recession was predicted by economists because the boom of the 1990s, accompanied by both low inflation and low unemployment, slowed in some parts of East Asia during the 1997 Asian financial crisis. The recession in industrialized countries was not as significant as either of the two previous worldwide recessions. Some economists in the United States object to characterizing it as a recession since there were no two consecutive quarters of negative growth.[citation needed] United States Percent Change From Preceding Period in Real Gross Domestic Product (annualized; seasonally adjusted) Average GDP growth 1970–2009  After the relatively mild 1990 recession ended in early 1991, the country hit a belated unemployment rate peak of 7.8% in mid-1992. Job growth was initially muted by large layoffs among defense related industries.[2] However, payrolls accelerated in 1992 and experienced robust growth through 2000.[3] Predictions that the bubble would burst emerged during the dot-com bubble in the late 1990s. Predictions about a future burst increased following the October 27, 1997 mini-crash, in the wake of the 1997 Asian financial crisis. This caused an uncertain economic climate during the first few months of 1998. However conditions improved, and the Federal Reserve raised interest rates six times between June 1999 and May 2000 in an effort to cool the economy to achieve a soft landing. The burst of the stock market bubble occurred in the form of the NASDAQ crash in March 2000. Growth in gross domestic product slowed considerably in the third quarter of 2000 to the lowest rate since a contraction in the first quarter of 1992.[4] According to the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER), which is the private, nonprofit, nonpartisan organization charged with determining economic recessions, the U.S. economy was in recession from March 2001 to November 2001,[5] a period of eight months at the beginning of President George W. Bush's term of office. The NBER's Business Cycle Dating Committee determined that a peak in business activity occurred in the U.S. economy in March 2001. A peak marks the end of an expansion and the beginning of a recession. The determination of a peak date in March is thus a determination that the expansion that began in March 1991 ended in March 2001 and a recession began.[5] The expansion lasted exactly 10 years, the longest in the NBER's chronology.[6] However, economic conditions did not satisfy the common shorthand definition of recession, which is "a fall of a country's real gross domestic product in two or more successive quarters", and has led to some confusion about the procedure for determining the starting and ending dates of a recession. The NBER's Business Cycle Dating Committee (BCDC) uses monthly, rather than quarterly, indicators to determine peaks and troughs in business activity,[7] as can be seen by noting that starting and ending dates are given by month and year, not quarters. However, controversy over the precise dates of the recession led to the characterization of the recession as the "Clinton Recession" by Republicans, if it could be traced to the final term of President Bill Clinton. BCDC members suggested they would be open to revisiting the dates of the recession as newer and more definitive data became available.[8] In early 2004, NBER President Martin Feldstein said:

However, in 2008, the NBER confirmed that the recession started in March 2001.[9] From mid-1999 to 2001, the Federal Reserve, in a move to protect the economy from the overvalued stock market, made successive interest rate increases. Using the stock market as an unofficial benchmark, a recession would have begun in March 2000 when the NASDAQ crashed following the collapse of the dot-com bubble. The Dow Jones Industrial Average was relatively unscathed by the NASDAQ's crash until the September 11 attacks, after which the Dow Jones suffered its worst one-day loss and largest one-week losses in history up to that point. The market rebounded, only to crash once more in the final two quarters of 2002. In the final three quarters of 2003, the market finally rebounded permanently, agreeing with the unemployment statistics that a recession defined in this way would have lasted from 2001 through 2003. The Labor Department estimates that a net 1.735 million jobs were shed in 2001, with an additional net 508,000 lost during 2002. 2003 saw a small gain of a mere 105,000 jobs. Unemployment rose from 4.2% in February 2001 to 5.5% in November 2001, but did not peak until June 2003 at 6.3%, after which it declined to 5% by mid-2005. CanadaCanada's economy is closely linked to that of the United States, and economic conditions south of the border tend to quickly make their way north. Canada's stock markets were especially hard hit by the collapse in high-tech stocks. For much of the 1990s the rapid rise of the TSX had almost wholly been attributed to two stocks: Nortel and BCE. Both companies were hard hit by the downturn, especially Nortel, which was forced to lay off much of its workforce. The September 11 attacks also hurt the Canadian stock markets and were especially devastating to the already troubled airline sector. However, in the wider economy, Canada was surprisingly unhurt by these events. While growth slowed, the economy never actually entered a recession. This was the first time that Canada had avoided following the United States into an economic downturn. The rate of job creation in Canada continued at the rapid pace of the 1990s. A number of explanations have been advanced to explain this. Canada was not as directly affected by 9/11 and the subsequent wars, and the downward pressure of these events was more muted. Canada's fiscal management during the period has been praised as the federal government continued to bring in large surpluses throughout this period, in sharp contrast to the United States. Unlike the United States no major tax cuts or major new expenditures were introduced. However, during this time, Canada did pursue an expansionary monetary policy in an effort to reduce the effects of a possible recession. Many provincial governments suffered greater problems with a number of them returning to deficits, which was blamed on the fiscal imbalance. 2003 saw elections in six Canadian provinces and in only one did the governing party not lose seats. RussiaThe Soviet Union's last year of economic growth was 1989, and throughout the 1990s, recession ensued in the Former Soviet Republics. In May 1998, following the 1997 crash of the East Asian economy, things began to get even worse in Russia. In August 1998, the value of the ruble fell 34% and people clamored to get their money out of banks (see 1998 Russian financial crisis). The government acted by dragging its feet on privatization programs. Russians responded to this situation with approval by electing the more pro-dirigist and less liberal Vladimir Putin as President in 2000. Putin proceeded to reassert the role of the federal government, and gave it power it had not seen since the Soviet era. State-run businesses were used to out-compete some of the more wealthy rivals of Putin. Putin's policies were popular with the Russian people, gaining him re-election in 2004. At the same time, the export-oriented Russian economy enjoyed considerable influx of foreign currency thanks to rising worldwide oil prices (from $15 per barrel in early 1999 to an average of $30 per barrel during Putin's first term). The early 2000s recession was avoided in Russia due to rebound in exports and, to some degree, a return to dirigisme. JapanJapan's recession, which started in the early 1990s, continued into the 2000s, with deflation being the main problem. Deflation began plaguing Japan in the fiscal year ending 1999, and by 2005 the yen had 103% of its 2000 buying power. The Bank of Japan attempted to cultivate inflation with high liquidity and a nominal 0% interest rate on loans. Other aspects of the Japanese economy were good during the early 2000s; unemployment remained relatively low, and China became somewhat dependent on the Japanese exports. The bear market, however, continued in Japan, despite the best efforts of the Bank. European Union Transition left the economy of the European Union in a cautiously optimistic state during the early 2000s. The most difficult years were 2000–2001, precipitating the worst years of the American recession. The European Union introduced a new currency on January 1, 1999. The euro, which was met with much anticipation, had its value immediately plummet, and it continued to be a weak currency throughout 2000 and 2001. Inflation struck the Eurozone for a few months in summer 2001 but the economy deflated within months. In 2002, the value of the euro began to rapidly rise (reaching parity with the US dollar on July 15, 2002). This hurt business for companies based in Europe, as the profits made abroad (especially in the Americas) had an unfavorable exchange rate. France and Germany both entered recession towards the end of 2001, but in May 2002 both countries declared that their recessions had ended after a mere six months each. Both economies suffered from global tech crash with the ruling German party introducing the then unpopular austerity, tax cuts and labor reforms nicknamed Hartz concept to boost the German economy in wake of an economic slump that would persist until the mid-2000s with unemployment peaking in early 2005 of 12.7%.[10] However, some European Union countries – including the United Kingdom – managed to delay sliding into recession until the late 2000s.[11] References

Further reading

|