|

Durian

The durian (/ˈdʊəriən/ ⓘ[1]) is the edible fruit of several tree species belonging to the genus Durio. There are 30 recognized species, at least nine of which produce edible fruit.[2] Durio zibethinus, native to Borneo and Sumatra, is the only species available on the international market. It has over 300 named varieties in Thailand and over 200 in Malaysia as of 2021. Other species are sold in their local regions.[2] Known in some regions as the "king of fruits",[3][4] the durian is distinctive for its large size, strong odour, and thorn-covered rind. The fruit can grow as large as 30 cm (12 in) long and 15 cm (6 in) in diameter, and it typically weighs 1 to 3 kg (2 to 7 lb). Its shape ranges from oblong to round, the colour of its husk from green to brown, and its flesh from pale yellow to red, depending on the species. Some people regard the durian as having a pleasantly sweet fragrance, whereas others find the aroma overpowering and unpleasant. The smell evokes reactions ranging from deep appreciation to intense disgust. The persistence of its strong odour, which may linger for several days, has led some hotels and public transportation services in Southeast Asia, such as in Singapore and Bangkok, to ban the fruit. The flesh can be consumed at various stages of ripeness, and it is used to flavour a wide variety of sweet desserts and savoury dishes in Southeast Asian cuisines. The seeds can be eaten when cooked. EtymologyThe name 'durian' is derived from the Malay word duri ('thorn'), a reference to the numerous prickly thorns on its rind, combined with the noun-building suffix -an.[5][6] According to the Oxford English Dictionary, the alternate spelling durion was first used in a 1588 translation of The History of the Great and Mighty Kingdom of China and the Situation Thereof by the Spanish explorer Juan González de Mendoza.[5] Other historical variant spellings include duryoen, duroyen, durean, and dorian.[5] The name of the type species, D. zibethinus, is derived from Italian zibetto (the civet).[7] DescriptionDurian trees are large, growing to 25–50 metres (80–165 feet) in height depending on the species.[8] The leaves are evergreen, elliptic to oblong and 10–18 centimetres (4–7 inches) long. The flowers are produced in three to thirty clusters together on large branches and directly on the trunk, with each flower having a calyx (sepals) and five (rarely four or six) petals. Durian trees have one or two flowering and fruiting periods per year, although the timing varies depending on the species, cultivars, and localities. A typical durian tree can bear fruit after four or five years. The durian fruit can hang from any branch, and matures roughly three months after pollination. The fruit can grow up to 30 cm (12 in) long and 15 cm (6 in) in diameter, and typically weighs 1 to 3 kilograms (2–7 lb).[8] Its shape ranges from oblong to round, the colour of its husk green to brown, and its flesh pale-yellow to red, depending on the species.[8] Among the thirty known species of Durio, nine produce edible fruits: D. zibethinus, D. dulcis, D. grandiflorus, D. graveolens, D. kutejensis, D. lowianus, D. macrantha, D. oxleyanus and D. testudinarius.[9] D. zibethinus is the only species commercially cultivated on a large scale and available outside its native region.[10] Since this species is open-pollinated, it shows considerable diversity in fruit colour and odour, size of flesh and seed, and tree phenology. In the species name, zibethinus refers to the Indian civet, Viverra zibetha. There is disagreement over whether this name, bestowed by Linnaeus, alludes to civets being so fond of the durian that the fruit was used as bait to entrap them, or to the durian's smelling like the civet.[11] Durian flowers are large and feathery, with copious nectar, and give off a heavy, sour, buttery odour. These features are typical of flowers pollinated by certain species of bats that eat nectar and pollen.[12] Durians can be pollinated by bats (the cave nectar bat Eonycteris spelaea, the lesser short-nosed fruit bat Cynopterus brachyotis, and the large flying fox, Pteropus vampyrus).[13] Two species, D. grandiflorus and D. oblongus, are pollinated by spiderhunter birds (Nectariniidae), while D. kutejensis is pollinated by giant honey bees and birds as well as by bats.[14] Some scientists have hypothesised that the development of monothecate anthers and larger flowers (compared with those of the remaining genera in Durioneae) in the clade consisting of Durio, Boschia, and Cullenia was in conjunction with a transition from beetle pollination to vertebrate pollination.[15]

CultivarsOver the centuries, numerous durian cultivars, propagated by vegetative clones, have arisen in Southeast Asia. They used to be grown, with mixed results, from seeds of trees bearing superior quality fruit. They are now propagated by layering, marcotting, or more commonly, grafting, including bud, veneer, wedge, whip and U-grafting, onto seedlings of randomly selected rootstocks. Different cultivars may be distinguished to some extent by variations in the fruit shape, such as the shape of the spines.[16] Malaysian varietiesThe Malaysian Ministry of Agriculture and Agro-Based Industry has since 1934 maintained a list of registered varieties, where each cultivar is assigned a common name and a code number starting with "D". These codes are widely used through Southeast Asia; as of 2021, there were over 200 registered varieties.[17] Many superior cultivars have been identified through competitions held at the annual Malaysian Agriculture, Horticulture, and Agrotourism Show. There are 13 common Malaysian varieties having favourable qualities of colour, texture, odour, taste, high yield, and resistance against various diseases.[18] Musang King (D197) was discovered in the 1980s, when a man named Tan Lai Fook from Raub, Pahang, stumbled upon a durian tree in Gua Musang, Kelantan. He brought a branch back to Raub for grafting. The cultivar was named after its place of origin.[19] The variety has bright yellow flesh and is like a more potent or enhanced version of the D24. The D24 or Sultan durian has golden yellow flesh and a rich texture and aroma. It is a popular variety in Malaysia.[19] Other popular cultivars in Malaysia include "Tekka", with a distinctive yellowish core in the inner stem; "D168" (IOI), which is round, of medium size, green and yellow outer skin, and easily dislodged flesh which is medium-thick, solid, yellow in colour, and sweet;[20] and "Red Prawn" (Udang Merah, D175), found in the states of Pahang and Johor.[21][22] The fruit is medium-sized, oval, brownish green, with short thorns. The flesh is thick, not solid, yellow-coloured, and has a sweet taste.[18] Indonesian varietiesIndonesia has more than 100 varieties of durian. The most cultivated species is D. zibethinus.[23] Notable varieties are Sukun (Central Java), Sitokong (Betawi), Sijapang (Betawi), Simas (Bogor), Sunan (Jepara), Si dodol and Si hijau (South Kalimantan),[23] and Petruk (Central Java).[23][24] Thai varietiesIn Thailand, Mon Thong is the most commercially sought after cultivar, for its thick, full-bodied creamy and mild sweet-tasting flesh with moderate smell and smaller seeds, while Chanee is most resistant to infection by Phytophthora palmivora. Kan Yao is less common, but prized for its longer window of time when it is both sweet and odourless. Among the cultivars in Thailand, five are currently in large-scale commercial cultivation: Chanee, Mon Thong, Kan Yao, Ruang, and Kradum.[25] By 2007, Thai government scientist Songpol Somsri had crossbred more than ninety varieties of durian to create Chantaburi No. 1, a cultivar without the characteristic odour.[26] Another hybrid, Chantaburi No. 3, develops the odour about three days after the fruit is picked, which enables an odourless transport yet satisfies consumers who prefer the pungent odour.[26] In 2012, two odourless cultivars, Long Laplae and Lin Laplae, were presented to the public by Yothin Samutkhiri, governor of Thailand's Uttaradit province where they were developed.[27]

Cultivation and trade In 2018, Thailand was ranked the world's number one exporter of durian, producing around 700,000 tonnes of durian per year, 400,000 tonnes of which are exported to mainland China and Hong Kong.[28] Chantaburi in Thailand holds the World Durian Festival in early May each year. This single province is responsible for half of the durian production of Thailand.[29][30] The Davao Region is the top producer of the fruit in the Philippines, producing 60% of the country's total.[31] In Brunei, consumers prefer D. graveolens, D. kutejensis, and D. oxleyanus. These species constitute a genetically diverse crop source.[32] Durian was introduced into Australia in the early 1960s, and clonal material followed in 1975. Over thirty clones of D. zibethinus and six other Durio species have been subsequently introduced into Australia.[33] In 2019 the value of imported fresh durian became the highest of all fresh fruits imported to China, which was previously cherries.[34] In 2021, China purchased at least US$3.4 billion worth or 90 percent of Thailand's fresh durian exports in that year.[35][36] Overall Chinese imports grew to $4 billion in 2022, when the Philippines and Vietnam gained permission to export fresh durians to China, and $6.7 billion in 2023 when 1.4 million tonnes were imported. Durian has become a status symbol indicating wealth. Durian from Thailand retails at around ¥150 (US$20), while the more prestigious Musang King variety retails at around ¥500 and can be a birthday or wedding gift. The potential value for exporters has allowed China to leverage durian as part of trade talks.[34] The entire export of durians from Southeast Asia to China increased from US$550 million in 2017, to US$6.7 billion in 2023.[37] China's largest imports of the fruit came from Thailand, followed by Malaysia and Vietnam.[37] Durian is a relatively costly fruit because of its short shelf life.[38] Shelf life can be extended to around 4 to 5 weeks by shrink wrapping each fruit. This inhibits dehiscence, probably by multiple mechanisms: inhibiting respiration; reducing loss of water; holding the fruit's parts together; and reducing decomposition by microbes.[39] The edible portion of the fruit, known as the aril and usually called the 'flesh' or 'pulp', only accounts for about 15–30% of the mass of the entire fruit.[40] Flavour and odourHistory  The strong flavour and odour of the fruit have prompted views ranging from appreciation to disgust.[2][41][42] Writing in 1856, the British naturalist Alfred Russel Wallace called the fruit's consistency and flavour "indescribable. A rich custard highly flavoured with almonds gives the best general idea of it, but there are occasional wafts of flavour that call to mind cream-cheese, onion-sauce, sherry-wine, and other incongruous dishes. Then there is a rich glutinous smoothness in the pulp which nothing else possesses, but which adds to its delicacy." He concluded that it provided a "new sensation worth a voyage to the East to experience. ... as producing a food of the most exquisite flavour it is unsurpassed."[43] Wallace described himself as being at first reluctant to try it because of the aroma, but on eating one in Borneo "out of doors, I at once became a confirmed Durian eater".[44] He cites another writer as stating: "To those not used to it, it seems at first to smell like rotten onions, but immediately after they have tasted it they prefer it to all other food. The natives give it honourable titles, exalt it, and make verses on it."[44] The novelist Anthony Burgess wrote that eating durian is "like eating sweet raspberry blancmange in the lavatory".[45] The travel and food writer Richard Sterling states that "its odor is best described as pig-excrement, turpentine and onions, garnished with a gym sock."[46] Other comparisons have been made with the civet, sewage, stale vomit, skunk spray and used surgical swabs.[41] Such descriptions may reflect the odour's variability.[47] Different species and cultivars vary markedly in aroma; for example, red durian (D. dulcis) has a deep caramel flavour with a turpentine odour while red-fleshed durian (D. graveolens) emits a fragrance of roasted almonds.[2] The fruit's strong smell has led to its ban from public transport systems in Singapore[48] and in Bangkok.[49] Biochemical basisA draft genome analysis of durian indicates it has about 46,000 coding and non-coding genes, among which a class called methionine gamma-lyases – which regulate the odour of organosulfur compounds – may be primarily responsible for the distinct odour.[50] Hundreds of phytochemicals responsible for durian flavour and aroma include diverse volatile compounds, such as esters, ketones, alcohols (primarily ethanol), and organosulfur compounds, with various thiols.[47][51] Ethyl 2-methylbutanoate had the highest content among esters in a study of several varieties.[47] Sugar content, primarily sucrose, has a range of 8–20% among different durian varieties.[47] Durian flesh contains diverse polyphenols, especially myricetin, and various carotenoids, including a rich content of beta-carotene.[47] In 2019, ethanethiol and its derivatives was identified as a source of the fetid smell. However, the biochemical pathway by which the plant produces ethanethiol remained unclear.[52] People in Southeast Asia with frequent exposures to durian are able to easily distinguish the sweet-like scent of its ketones and esters from rotten or putrescine odours which are from volatile amines and fatty acids. Some individuals are unable to differentiate these smells and find this fruit noxious, whereas others find it pleasant and appealing.[2][41][42] This strong odour can be detected half a mile away by animals, thus luring them. In addition, the fruit is highly appetising to diverse animals, including squirrels, mouse deer, pigs, sun bear, orangutan, elephants, and even carnivorous tigers.[53][54] While some of these animals swallow the seed with the fruit and then transport it some distance before excreting, thus dispersing the seed.[55] The thorny, armoured covering of the fruit discourages smaller animals; larger animals are more likely to transport the seeds far from the parent tree.[56] Ripeness and selectionAccording to Larousse Gastronomique, the durian fruit is ready to eat when its husk begins to crack.[57] However, the ideal stage of ripeness to be enjoyed varies from region to region in Southeast Asia and by species. Some species grow so tall that they can only be collected once they have fallen to the ground, whereas most cultivars of D. zibethinus are nearly always cut from the tree and allowed to ripen while waiting to be sold. Some people in southern Thailand prefer their durians relatively young, when the clusters of fruit within the shell are still crisp in texture and mild in flavour. For some people in northern Thailand, the preference is for the fruit to be soft and aromatic. In Malaysia and Singapore, most consumers prefer the fruit to be as ripe and pungent in aroma as possible and may even risk allowing the fruit to continue ripening after its husk has already cracked open. In this state, the flesh becomes richly creamy and slightly alcoholic.[41] The various preferences regarding ripeness among consumers make it hard to issue general statements about choosing a "good" durian. A durian that falls off the tree continues to ripen for two to four days, but after five or six days most would consider it overripe and unpalatable.[2] All the same, some Thais cook such overripe fruit with palm sugar, creating a dessert called durian (or thurian) guan.[58] UsesCulinaryIn Thailand, durian is eaten fresh with sweet sticky rice, and blocks of durian paste are sold in the markets, though much of the paste is adulterated with pumpkin.[2] Unripe durians are cooked as a vegetable, except in the Philippines, where all uses are sweet rather than savoury. Malaysians make both sugared and salted preserves from durian. When durian is minced with salt, onions and vinegar, it is called boder. In Kelantan of Malaysia, fresh durian or tempoyak is mixed with onion and chilli slices, lime juice and budu (fermented anchovy sauce) and eaten as a condiment with rice-based meals. The seeds, which are the size of chestnuts, can be eaten boiled, roasted or fried in coconut oil, with a texture that is similar to taro or yam, but stickier. In Java, the seeds are sliced thin and cooked with sugar as a confection. Uncooked seeds are potentially toxic due to cyclopropene fatty acids.[59]

Durian fruit is used to flavour a wide variety of sweet edibles such as traditional Malay candy, ice kacang, dodol, lempuk,[60] rose biscuits, ice cream, milkshakes, mooncakes, Yule logs, and cappuccino. Es durian (durian ice cream) is a popular dessert in Indonesia, sold at streetside stalls in Indonesian cities, especially in Java. Pulut durian or ketan durian is glutinous rice steamed with coconut milk and served with ripened durian. In Sabah, red durian is fried with onions and chilli and served as a side dish.[61] Red-fleshed durian is traditionally added to sayur, an Indonesian soup made from freshwater fish.[4] Ikan brengkes tempoyak is fish cooked in a durian-based sauce, traditional in Sumatra.[62]

Nutrition

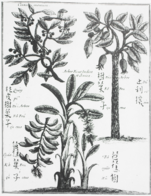

Raw durian is composed of 65% water, 27% carbohydrates (including 4% dietary fibre), 5% fat and 1% protein. In 100 grams, raw or fresh frozen durian provides 33% of the Daily Value (DV) of thiamine and a moderate content of other B vitamins, vitamin C, and the dietary mineral manganese (15–24% DV, table). Different durian varieties from Malaysia, Thailand and Indonesia vary in their carbohydrate content from 16 to 29%, fat content from 2–5%, protein content from 2–4%, and dietary fibre content from 1–4%, and in caloric value from 84 to 185 kcal per 100 grams.[47] The fatty acids in durian flesh are particularly rich in oleic acid and palmitic acid.[47] Origin and historyThe origin of the durian is thought to be in the region of Borneo and Sumatra, with wild trees in the Malay Peninsula and orchards commonly cultivated in a wide region from India to New Guinea.[2] Four hundred years ago, it was traded across present-day Myanmar and was actively cultivated especially in Thailand and South Vietnam.[2] The earliest known European reference to the durian is the record of Niccolò de' Conti, who travelled to Southeast Asia in the 15th century.[65] Translated from the Latin in which Poggio Bracciolini recorded de Conti's travels: "They [people of Sumatra] have a green fruit which they call durian, as big as a watermelon. Inside there are five things like elongated oranges, and resembling thick butter, with a combination of flavours."[66] The Portuguese physician Garcia de Orta described durians in Colóquios dos simples e drogas da India published in 1563. In 1741, Herbarium Amboinense by the German botanist Georg Eberhard Rumphius was published, providing the most detailed and accurate account of durians for over a century. The genus Durio has a complex taxonomy that has seen the subtraction and addition of many species since it was created by Rumphius.[9] During the early stages of its taxonomical study, there was some confusion between durian and the soursop (Annona muricata), for both of these species had thorny green fruit.[67] The Malay name for the soursop is durian Belanda, meaning Dutch durian.[68] In the 18th century, Johann Anton Weinmann considered the durian to belong to Castaneae as its fruit was similar to the horse chestnut.[67] A plate from Michał Boym's 1655 account of China, showing cinnamon, durian, and plantain Durio zibethinus. Chromolithograph by Hoola Van Nooten, circa 1863 D. zibethinus was introduced into Ceylon by the Portuguese in the 16th century and was reintroduced many times later. It has been planted in the Americas but confined to botanical gardens. The first seedlings were sent from the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, to Auguste Saint-Arroman of Dominica in 1884.[69] In Southeast Asia, the durian has been cultivated for centuries at the village level, probably since the late 18th century, and commercially since the mid-20th century.[2][70] In My Tropic Isle, Australian author and naturalist Edmund James Banfield tells how, in the early 20th century, a friend in Singapore sent him a durian seed, which he planted and cared for on his tropical island off the north coast of Queensland.[71] In 1949, the British botanist E. J. H. Corner published The Durian Theory, or the Origin of the Modern Tree. This proposed that endozoochory (the enticement of animals to transport seeds in their stomach) arose before any other method of seed dispersal and that primitive ancestors of Durio species were the earliest practitioners of that dispersal method, in particular red durian (D. dulcis) exemplifying the primitive fruit of flowering plants. However, in more recent circumscriptions of Durioneae, the tribe into which Durio and its sister taxa fall, fleshy arils and spiny fruits are derived within the clade. Some genera possess these characters, but others do not. The most recent molecular evidence (on which the most recent, well-supported circumscription of Durioneae is based) therefore refutes Corner's Durian Theory.[15] Since the early 1990s, the domestic and international demand for durian in the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) region has increased significantly.[72] In the early 2020s, a durian craze in China led to a large increase in international trade of the fruit.[73] Culture and folk medicineCultural influencesA common local belief is that the durian is harmful when eaten with coffee[41] or alcoholic beverages.[74] The latter belief can be traced back at least to the 18th century when Rumphius stated that one should not drink alcohol after eating durians as it will cause indigestion and bad breath. In 1929, J. D. Gimlette wrote in his Malay Poisons and Charm Cures that the durian fruit must not be eaten with brandy. In 1981, J. R. Croft wrote in his Bombacaceae: In Handbooks of the Flora of Papua New Guinea that "a feeling of morbidity" often follows the consumption of alcohol too soon after eating durian. Several medical investigations on the validity of this belief have been conducted with varying conclusions,[74] though a study by the University of Tsukuba finds the fruit's high sulphur content inhibits the activity of aldehyde dehydrogenase, causing a 70 percent reduction of the ability to clear certain toxins such as alcohol from the body.[75]   In its native Southeast Asia, the durian is an everyday food and portrayed in the local media in accordance with the cultural perception it has in the region. The durian symbolised the subjective nature of ugliness and beauty in Hong Kong director Fruit Chan's 2000 film Durian Durian (榴槤飄飄, lau lin piu piu), and was a nickname for the reckless but lovable protagonist of the eponymous Singaporean TV comedy Durian King played by Adrian Pang.[76] Likewise, the oddly shaped Esplanade building in Singapore (Theatres on the Bay) is often called "The Durian" by locals,[76] and "The Big Durian" is the nickname of Jakarta, Indonesia.[77] A saying in Malay and Indonesian, mendapat durian runtuh, "getting a fallen durian", is the equivalent of the English phrase 'windfall gain'.[78] Nevertheless, trees bearing mature durians are dangerous because the fruit is heavy, armed with sharp thorns, and can fall from a significant height. Hardhats are worn when collecting the fruit. A common saying is that a durian has eyes, and can see where it is falling, because the fruit supposedly never falls during daylight hours when people may be hurt.[79][80][81] In Malaysia, a spineless durian clone D172 was registered by the Agriculture Department in 1989. It was called "Durian Botak" ('Bald Durian').[82] Sumatran elephants and tigers sometimes eat durians.[54] Being a fruit much loved by a variety of animals, the durian is sometimes taken to signify the animalistic aspect of humans, as in the legend of Orang Mawas, the Malaysian version of Bigfoot, and Orang Pendek, its Sumatran version, both of which have been claimed to feast on durians.[83][84] Folk medicineIn Malaysia, a decoction of the leaves and roots used to be prescribed as an antipyretic. The leaf juice is applied on the head of a fever patient.[2] The most complete description of the medicinal use of the durian as remedies for fevers is a Malay prescription, collected by Burkill and Haniff in 1930. It instructs the reader to boil the roots of Hibiscus rosa-sinensis with the roots of Durio zibethinus, Nephelium longana, Nephelium mutabile and Artocarpus integrifolius, and drink the decoction or use it as a poultice.[85] Southeast Asian traditional beliefs, as well as traditional Chinese food therapy, consider the durian fruit to have warming properties liable to cause excessive sweating.[86] The traditional method to counteract this is to pour water into the empty shell of the fruit after the pulp has been consumed and drink it.[41] An alternative method is to eat the durian in accompaniment with mangosteen, which is considered to have cooling properties. Pregnant women or people with high blood pressure are traditionally advised not to consume durian.[26][87] The Javanese believe durian to have aphrodisiac qualities, and impose a set of rules on what may or may not be consumed with it or shortly thereafter.[41] A saying in Indonesian, durian jatuh sarung naik, meaning "the durian falls and the sarong comes up", refers to this belief.[88] The warnings against the supposed lecherous quality of this fruit soon spread to the West – the Swedenborgian philosopher Herman Vetterling commented on so-called "erotic properties" of the durian in the early 20th century.[89] Environmental impactThe high demand for durians in China has prompted a shift in Malaysia from small-scale durian orchards to large-scale industrial operations. Forests are cleared to make way for large durian plantations, compounding an existing deforestation problem caused by the cultivation of oil palms.[90] Animal species such as the small flying fox, which pollinates durian trees, and the Malayan tiger are endangered by the increasing deforestation of their habitats.[90][91] In the Gua Musang District, the state government approved the conversion of 40 km2 (10,000 acres) of forestry, including indigenous lands of the Orang Asli, to durian plantations.[92] The prevalence of the Musang King and Monthong varieties in Malaysia and Thailand, respectively, has led to concerns about a decrease in the durian's genetic diversity at the expense of higher-quality varieties.[90] A 2022 study of durian species in Kalimantan, Indonesia, found low genetic diversity, suggestive of inbreeding depression and genetic drift.[93] Additionally, these dominant hybrid varieties are more susceptible to pests and fungal diseases, requiring the use of insecticides and fungicides that can weaken the trees.[90] See alsoReferences

Sources

External links |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||