|

Diyi

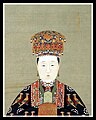

Diyi (Chinese: 翟衣; lit. 'pheasant garment'; Korean: 적의; Hanja: 翟衣), also called known as huiyi (simplified Chinese: 袆衣; traditional Chinese: 褘衣) and miaofu (Chinese: 庙服), is the historical Chinese attire worn by the empresses of the Song dynasty[1] and by the empresses and crown princesses (wife of crown prince) in the Ming Dynasty. The diyi also had different names based on its colour, such as yudi, quedi, and weidi.[2] It is a formal wear meant only for ceremonial purposes. It is a form of shenyi (Chinese: 深衣), and is embroidered with long-tail pheasants (Chinese: 翟; pinyin: dí or Chinese: 褘; pinyin: hui) and circular flowers (Chinese: 小輪花; pinyin: xiǎolúnhuā). It is worn with guan known as fengguan (lit. 'phoenix crown') which is typically characterized by the absence of dangling string of pearls by the sides. It was first recorded as Huiyi in the Zhou dynasty.[3] Terminology and formsThe diyi has been worn by empresses and other royal noblewomen (differs according to different dynasties) since the Zhou dynasty.[4] Since the Zhou dynasty, the diyi continued to be worn in the Northern and Southern dynasties, Sui, Tang, Song, Ming dynasties[5] under various names: huiyi in Zhou and Song dynasty,[3] and miaofu in Han dynasty.[4] Diyi also has several forms, such as yudi (Chinese: 褕翟) which was dyed in indigo (Chinese: 青; pinyin: qing), quedi (Chinese: 闕翟; lit. 'pheasant garments') which was dyed in red, and weidi (Chinese: 褘翟) which was dyed in black; they were all form of ritual clothing which was worn by royal women during ceremonies.[2] Cultural significance and symbolismThe diyi follows the traditional Confucian standard system for dressing, which is embodied in its form through the shenyi system. The garment known as shenyi is itself the most orthodox style of clothing in traditional Chinese Confucianism; its usage of the concept of five colours, and the use of di-pheasant bird pattern.[3] Pheasant pattern The di-bird pattern forms part of the Twelve Ornaments and is referred as huachong (simplified Chinese: 华虫; traditional Chinese: 華蟲).[3] The pattern of paired pheasant on the diyi is called yaohui.[1] The di-bird pattern is symbolism for "brilliance"; and the bird itself is a type of divine birds of five colours which represents the Empress' virtue. These five colours (i.e. blue, red, black, yellow, white) also correspond to the five elements; and thus, the usage of di-bird pattern aligns with the traditional colour concept in Confucianism.[3] Small circular flowers The small circular flowers known as xiaolunhua (Chinese: 小輪花; pinyin: Xiǎolúnhuā), also known as falunhua (Chinese: 法轮花), which originated from the Buddhism's Rotating King and from the era of the Maurya dynasty.[3] They are placed between each pair of di-bird pattern on the robe.[3] The little flowers looks like a small wheel-shaped flower.[6] Shenyi systemThe use of shenyi for women does not only represent its wearer's noble status but also represents the standard of being faithful to her spouse undo death.[3] The shenyi was the most appropriate ceremonial clothing style of clothing for the Empress due to its symbolic meaning: it represented the harmony between Heaven, earth, and space.[3] The shenyi consists of an upper garment and a lower garment which represents the concept of Heaven and Earth (Chinese: 两仪; pinyin: Liangyi); the upper garment is made of 4 panels of fabric representing the four seasons, and the lower garment is made of 12 panels of fabric which represents the time of the year.[3] The wide cuff sleeves are round-shaped to symbolize the sky and the Confucian's scholars' deep knowledge and integration while the right-angled collar is square shaped to represents the earth warning Confucians that they should have integrity and kindness; together, the sleeves and the right-angled collar represents space as the circle and the square of the world.[3] The back of the shenyi is composed of two fabrics which are vertically sewed together and the large waist belt represents the privileged classes and is a symbolism for uprightness and honesty; it also meant fairness held by those with power.[3] HistoryZhou dynastyThe huiyi is an ancient system which was first recorded in the Zhou dynasty (c. 1046 BC – 256 BC).[3] It was first recorded and codified in the Rites of Zhou (Chinese: 周礼; pinyin: Zhouli).[1][3][7] Huiyi was the highest of the empresses' six occasional clothing (pinyin: liufu).[1] The huiyi in Zhou dynasty was worn by the Empress as ceremonial clothing to pay respect during the ancestral shrine sacrifice which was the most important sacrificial event in which they could participate in.[3] Following the Zhou dynasty, the subsequent dynasties perceived the huiyi as the highest form of ceremonial clothing.[3] According to the Zhou dynasty rites, there were two types of black and blue clothing; however, there is currently no proof that the huiyi in the Zhou dynasty was black in colour.[3] Sui and Tang dynastyThe huiyi in Sui and Tang dynasties was also blue in colour.[3] Song dynastyIn the Song dynasty, the huiyi was the highest form of ceremonial clothing worn by the Empress; it was worn on important ceremonial occasions such as wedding, coronations, when holding court, and during ancestral shrine sacrifices.[3] The Huiyi was made out of dark blue zhicheng (a kind of woven fabric).[8]: 110 When empress wears the huiyi, she also needs to wear a phoenix crown, a blue inner garment and a dark blue bixi, with blue socks and shoes, along with a pair of jade pendants and other jade ornaments.[8]: 110 The early Song dynasty sanlitu (Chinese: 三礼图) shows illustration of the huiyi as being a form of shenyi (Chinese: 深衣), being deep blue and is decorated with di bird patterns.[3] In the Records of Chariots and Horses and Clothes written in the Yuan dynasty, the Song dynasty huiyi is described as being dark blue in colour and there are 12 lines of di birds which stand together in pair.[3] There is a bixi (a knee covering) which hangs in the central region of the front skirt; the colour of bixi has the same colour as the bottom of the lower skirt.[3] Di bird patterns can decorate the black, red collar edge in 3 lines.[3] There is also a belt which is divided into a large belt made of silk (which is dark blue in with red lining with the upper surface part made of red brocade while the lower part made of green brocade) and narrow leather belt (which is cyan in colour decorated with white jade in pairs) is on top of the large silk belt.[3] The socks are dark blue in colour; the shoes are also dark blue but decorated with gold ornaments.[3] The literature which describes the Song dynasty huiyi however does not always provide details (e.g. variations) which can be found in the Song dynasty court painting and some discrepancies can be found between the text and the paintings.[3] From the several court portrait paintings of the Song dynasty, it is found that the huiyi was cross-collar closing to the right, with large and wide sleeves, and with cloud and dragons patterns ornamenting the collar, sleeves and placket, with a belt worn around the waist; and while all the huiyi were depicted as being deep blue in colour, they differed in shades of dark blue showing variation.[3] Instead of being in three lines as described in the Yuan dynasty's records, in the Song paintings, the di bird pattern which decorates the belts is denser.

Ming dynasty The Huiyi was also the ceremonial dress of the empress in the Ming dynasty.[8]: 150 In the Ming dynasty, the huiyi was composed of the phoenix crown, the xiapei, an overdress and long-sleeved blouse.[8] In the Ming dynasty, there are however different kinds of phoenix crowns depending on the ranks of its wearer: the one for the empresses is decorated with 9 dragons and 4 phoenixes, and the ones for the imperial concubines had 9 multicoloured pheasants and 4 phoenixes, and the other for the titled women was called a coloured coronet, which was not decorated with dragons or phoenixes but with pearls, feathers of wild fowls and flower hairpins.[8] The quedi is dyed in red instead of blue.[2]

Qing dynasty

Modern Restoration

Influences and derivativesJapanIn Japan, the features of the Tang dynasty-style huiyi was found as a textile within the formal attire of the Heian Japanese empresses.[5] Korea Korean queens started to wear the jeokui (Korean: 적의; Hanja: 翟衣) in 1370 AD under the final years of Gongmin of Goryeo,[9] when Goryeo adopted the official ceremonial attire of the Ming dynasty.[6] In the Joseon dynasty, the official dress worn by queens was wearing the jeokui which was adopted from the Ming dynasty's diyi.[9] The jeokui was a ceremonial robe which was worn by the Joseon queens on the most formal occasions.[6] It was worn together with jeokgwan (Korean: 적관; Hanja: 翟冠) in the late Goryeo and early Joseon, hapi (Korean: 하피; Hanja: 霞帔), pyeseul (Korean: 폐슬; Hanja: 蔽膝).[10][6][11] According to the Annals of Joseon, from 1403 to the first half of the 17th century the Ming dynasty sent a letter, which confers the queen with a title along with the following items: jeokgwan, a vest called baeja (Korean: 배자; Hanja: 褙子), and a hapi.[10] However, the jeokui sent by the Ming dynasty did not correspond to those worn by the Ming empresses as Joseon was considered to be ranked two ranks lower than Ming.[6] Instead the jeokui which was bestowed corresponded to the Ming women's whose husband held the highest government official posts.[6] The jeokdui worn by the queen and crown princess was originally made of red silk; it then became blue in 1897 when the Joseon king and queen were elevated to the status of emperor and empress.[12] In early Joseon, from the reign of King Munjong to the reign of King Seonjo, the queen wore a plain red ceremonial robe with wide sleeves (daehong daesam; Korean: 대홍대삼; Hanja: 大紅大衫, also referred as daesam for short).[13][14] The daesam is believed to be similar in form to the Ming dynasty's daxiushan, which was worn by the titled court women of the first rank.[14] The daesam was another garment which was bestowed by the Ming dynasty from the reign of King Munjong of early Joseon to the 36th year of King Seonjo's reign in 1603; it continued to be worn even after the fall of the Ming dynasty.[14]   Following the fall of the Ming dynasty, Joseon established their own jeogui system.[6] In the late Joseon, the daesam was modified to feature pheasant heads and a rank badge.[13] In the Korea Empire, the blue jeokui was established for the Korea Empress.[13] An example of the jeokui worn by the Korean empresses in Joseon can be seen in the Cultural Heritage Administration website. The xiaolunhua (小輪花) motif are known as ihwa motif in Korea.[6] The Korean ihwa motif were likely designed in 1750 when Joseon established their own jeokui system, and may have used The Collected Statutes of the Ming Dynasty (大明會典) as reference.[6] By the Korea Empire, the ihwa motif was revised and became one of the primary emblem of the Korean empire.[6] The jeokgwan was the Chinese crown decorated with pheasant motifs; it was worn by the queens and princesses of the Ming dynasty.[15] The jeokgwan originated from the bonggwan (Korean: 봉관; Hanja: 鳳冠) which was worn from by the Chinese empresses.[15] The jeokgwan was bestowed to Princess Noguk in late Goryeo by Empress Ma of Ming;[10] it continued to bestowed in Joseon until the early 17th century.[15][10] It stopped being bestowed after the fall of the Ming dynasty.[10] In the late Joseon, the jeokgwan was changed into a big wig, called daesu which consisted with a gache and binyeo, following extensive reforms.[15] The daesu was then worn until the end of Joseon.[10] 2 variations of the diyi had been developed in Korea during the Joseon dynasty, and later in the Korean Empire. The developments were as follows:

Diyi were worn by:

VietnamAccording to the book, Weaving a Realm (Dệt nên triều đại) published by Vietnam Centre, the diyi (Sino-Vietnamese: Địch Y; 翟衣) was recorded as Huy Địch (褘翟) in Vietnam and was recorded in the book, Tang thương ngẫu lục 桑滄偶錄.[18] According to the Vietnam Centre, the diyi might have historically been worn by the Vietnamese empress in Vietnam due to the existence of this sole record so far:[19]

See alsoNotes and references

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||