|

Chinese hairpin

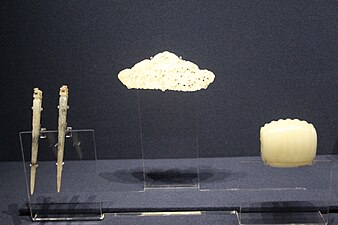

Ji (Chinese: 筓; pinyin: jī) (also known as fazan (Chinese: 髮簪; pinyin: fàzān), fanzi (Chinese: 簪子; pinyin: zānzi) or zan (Chinese: 簪; pinyin: zān) for short)[1][2] and chai (Chinese: 钗; pinyin: chāi) are generic terms for hairpin in China.[3] Ji (with the same character of 笄) is also the term used for hairpins of the Qin dynasty.[4] The earliest form of Chinese hair stick was found in the Neolithic Hemudu culture relics; the hair stick was called ji (笄), and were made from bones, horns, stones, and jade.[5] Hairpins are an important symbol in Chinese culture,[1] and are associated with many Chinese cultural traditions and customs.[6] They were also used as every day hair ornaments in ancient China;[3] all Chinese women would wear a hairpin, regardless of their social rank.[7] The materials, elaborateness of the hairpin's ornaments, and the design used to make the hairpins were markers of the wearer's social status.[1][6] Hairpins could be made out of various materials, such as jade, gold, silver, ivory, bronze, bamboo, carved wood, tortoiseshell and bone, as well as others.[3][8][1][9] Prior to the establishment of the Qing dynasty, both men and women coiled their hair into a bun using a ji.[3] There were many varieties of hairpin, many having their own names to denote specific styles, such as zan, ji, chai, buyao and tiaoxin.[10][3][11] CulturalBurialsDuring the Chinese funeral period, women in mourning were not allowed to wear hairpins.[1] Ji ceremonyJi played an important role in the coming-of age of Han Chinese women.[1][4] Before the age of 15 years old, women did not use hairpins, and always kept their hair in braids.[1] When a woman turned 15, she stopped wearing braids, and a hairpin ceremony called "Ji Li" (笄礼), or "hairpin initiation", would be held to mark the rite of passage.[3][1][6][4] During the ceremony, their hair would be coiled into a bun with a ji hairpin.[1][4] After the ceremony, the woman would be eligible for marriage.[3][6][4] Hairpins as a love tokenBetrothal and wedding customsWhen engaged to be married, Chinese women would take the hairpin from their hair and give it to their male fiancé.[1] After the wedding, the husband would then return the hairpin to his newly-wed wife by placing it back in her hair.[1] Separation and reunion love tokenThe chai hairpin[12] also used to be a form of love token; when lovers were forced to break apart, they would often break a hairpin in half, and each would keep half of the hairpin until they were reunited.[3] Similarly, when married couples were separated for a long period of time, they would break a hairpin in two and each keep one part.[1] If they were to meet again in the future, they would then put the hairpin together again, as a proof of their identity and as a symbol of their reunion.[1] Design and constructionMaterials Initially, Chinese people liked hairpins which were made out of bone and jade.[13] Hairpins which were made out of carved jade appeared in China as early as the Neolithic Period (c. 3000–1500 BC), along with jade carving technology.[7] Some ancient Chinese hairpins dating from the Shang dynasty can still be found in some museums.[14] By the Bronze Age, hairpins which were made out of gold had been introduced into China by people living on the country's Northern borders.[13] Some ancient Chinese hairpins dating back to 300 BC were made from bone, horn, wood, and metal.[8] The art of engraving wood first appeared in the Tang dynasty, and this new form of art was then applied to large wooden Chinese hairpins.[15] Many of these wooden hairpins were then coated with silver.[15] In the Ming dynasty, the hairpins became more elaborate, and the carvings were made on silver, ivory, and jade, with pearl being used often as a setting.[15] DecorationsHairpins could also be decorated with gemstones, as well as designs of flowers, dragons, and phoenixes.[8] TypesThere are various types of Chinese hairpins: ZanThe Zan is a type of hairpin with a single pin.[10][9] The Zan could also come in different styles such as:[10]

Phoenix hairpinPhoenix (Fenghuang) hairpin originated in Qin dynasty and had an upper part made of gold and silver while the feet was made of tortoise shell; it later evolved into the fengguan during the Song dynasty. The fengguan then continued to evolve further in the Ming and Qing dynasties, and in the modern republic.[16] In the Han dynasty, an imperial edict decreed that the hairpin with fenghuang decorations had to become the formal headpiece for the empress dowager and the imperial grandmother.[16] The Fenghuang is an auspicious bird in Chinese tradition and is believed to represent the empress or the bride in a wedding.[17] Phoenix hairpins were also made and used by Peranakan women after settling in the Straits as part of their wedding headdresses.[17]

ChaiThe chai is a type of hairpin with double or multiple pins.[10][9] The double-pin chai evolved from the zan; it was frequently found in Chinese poetry and literature as it played an important symbol and as a love token.[12]

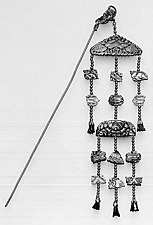

BuyaoThe buyao was an elaborate and exquisite form of hairpin which denoted noble status.[3] It was generally made of gold and was often decorated with jewels (such as pearls and jade) and carved designs (such as in the shape of dragons or phoenix).[3][13] It looked similar to a zan,[12] but one of its main characteristics is its dangling features, which gave it its name 'buyao' (lit. "shake as you go" or "that sway with each step" or "step shake").[3][9][18][12] The buyao became popular in the Western Han dynasty.[13]

Diancui hairpinThe diancui hairpin, also known as "kingfisher feather hairpin",[19] were made using the traditional Chinese art of diancui.[18]

Flower-hairpin headdressesThe Flower-hairpin headdresses is a generic term which was used to refer to the jewelry and headdresses worn by the Song dynasty Empresses and imperial concubines.[20] The Flower-hairpin headdresses were decorated with flower hairpins.[20] Different numbers of flowers were used depending on the imperial consorts' ranks and specific imperial rules were issued on their usage.[20] Jin chan yu yueJin Chan yu yue (Chinese: 金蟬玉葉); pinyin: Jīn chán yù yè) Known as the "gold cicada on a jade leaf" hairpin, or "jin zhi yu ye" "Jin zhi yu yue" (Chinese: 金枝玉葉); pinyin: Jīnzhīyùyè) (lit. golden branches and jade leaves) a homonym for the Chinese idiom "one of noble birth",[21] a type of Ming dynasty hairpin in the shape of a cicada made of gold sitting on a piece of jade carved in the shape of a leaf.[9][21] TiaoxinThe Tiaoxin (Chinese: 挑心); pinyin: Tiāo xīn) is a Chinese hairpin worn by women in the Ming dynasty in their hair bun; the upper part of the hairpin was usually in the shape of a Buddhist statue, an immortal, a Sanskrit word, or a phoenix.[11] The Chinese character shou (寿, "longevity") could also be used to decorate the hairpin.[11][22] See also

References

|

||||||||