|

Distance education in Chicago Public Schools in 1937

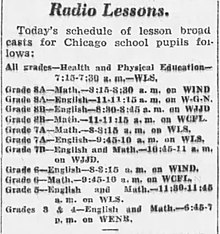

In September 1937, amid a polio outbreak in Chicago, Chicago Public Schools undertook a pioneering large-scale program that provided at-home distance education to the city's elementary school students through lessons transmitted by radio broadcasts and materials published in newspapers.[1][2] BackgroundIn 1937, Chicago was hit by a polio outbreak. On August 31, the Chicago Board of Health, led by Herman Bundesen, ordered an indefinite postponement of the opening of schools, which had been scheduled to begin their fall semesters on September 7.[1][3][4] President of the Chicago Board of Education James B. McCahey announced on September 2 that schools would remain "indefinitely closed".[5] The school closures ultimately lasted three weeks.[3] Earlier instances of distance education by radioChicago's program is regarded as the first large-scale experiment with "radio school".[2] Earlier, smaller-scale uses of radio for distance education had preceded this. In 1930, during a school closure in Marquette, Michigan, the station WBEO worked with the Daily Mining Journal to provide students with audible and textual instruction. This 1930 implementation had been regarded as a success.[6] Chicago had seen one instance of distance learning by radio five years earlier, in 1932, when, after the Chicago Board of Education cancelled summer school due to lack of funding, NBC privately produced a Summer School of the Air on their station WMAQ. For this program, NBC employed their own educators and printed their own textbooks.[6][7] Distance education programIn order to provide elementary school students with instruction during the indefinite school closure, superintendent of Chicago Public Schools William Johnson and assistant superintendent in charge of elementary schools Minnie Fallon developed a distance learning program that provided the students in grades three through eight with instruction via radio broadcasts.[3][8][4] The idea for such a program was first suggested by George H. Biggar of station WLS.[6] Distance learning instruction was, ultimately, broadcast for two weeks, beginning on September 13. Elementary schools reopened for in-person instruction on September 27.[2][9] Regarded to have been the first large scale experiment with "radio school",[2] Chicago's experiment with it attracted the interest of educators across the United States.[3] The idea of using radio to facilitate distance learning was considered innovative and untested.[3] Out-of-city newspapers even sent correspondents to Chicago to report on it, and newsreels were created that reported on Chicago's experiment in mass distance education by radio.[4] Fallon cited a belief that children in the elementary school grades first and second required more individual attention are not adaptable to distance education as the reason that those grades were not provided with such instruction.[10] Johnson cited a lack of enough radio air time as the reason that high school students were not part of the program either.[10] Johnson recommended that high school students spend the period of the school closures reviewing their notebooks from their previous semester of school.[10] It was also believed that high school students would be mature enough to review their previous year's material on their own.[6] High schools would ultimately be closed for a shorter period than elementary schools, returning to in-person instruction on September 16, a day after the Chicago Board of Health determined that it was it safe for high schools to reopen but still unsafe for elementary schools to.[4]  Lessons were presented in 15-minute slots of airtime.[3] Airtime was donated by the radio stations WCFL, WENR, WGN, WIND, WJJD, and WLS.[3] The lessons were written by teachers and principals.[3] WLS built special studios in the headquarter building of the Chicago Board of Education for the broadcasts.[6] Lillian M. Tobin was put in charge of the curriculum.[11] Oversight was provided by "subject area committees" that were tasked with ensuring quality and continuity in the lessons.[3] Efforts were taken to make the broadcasts entertaining to students, in order to better engage them. For instance, explorer Carveth Wells was booked to speak during some of the broadcasts.[3] Each day’s instruction began at 7:15 am with the program for the day being read by August H. Pritzlaff, the head of Chicago Public Schools' physical education department.[10] Lessons were scheduled in such as manner that different days of the week were dedicated to different subjects. Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays were dedicated to science and social studies, while Tuesdays, Thursdays, and Saturdays were dedicated to English studies and mathematics.[3] Broadcast schedules, as well as directions, questions, and assignments were published in the city's newspapers,[3] with six city newspapers cooperating.[12] A helpline was established in order to allow parents to provide comment, as well as to help answer questions parents would have about the radio programs and the epidemic, with educational personnel manning the hotline.[3][8] Parents were encouraged to supplement the lessons by facilitating daily study periods with their children following the broadcasts.[3] In order to educate students who missed broadcasts, such as those who not have access to a radio or those who encountered poor reception, make-up work was created.[3] Once they returned to in-person learning, students were tested on the material that had been covered by the radio broadcasts and newspaper publications.[8] The purpose of these tests was both to assess the effectiveness of the instruction,[13] as well as to decide what grade credit each student would receive for their work on the radio lessons.[12] AnalysisSuperintendent Johnson gave the estimate that 315,000 students listened to the radio lessons, but also stated that it was "impossible to give an accurate check".[12] A criticism of the format utilized was that some students found that the broadcasts, with their condensed time slots, moved at too fast a pace, resulting in these students missing crucial pieces of information.[3] Another shortcoming was that there was not universal access to radios, resulting in some students being unable to listen to the broadcasts.[3] Additionally, in houses that had multiple children of different grades but only one radio, conflicts would arise if their children had coincidingly scheduled lessons.[3] The radio format was seen to be inadequate at providing instruction to students that required greater attention or remediation.[3] Some educators and analysts proposed the possibility that "the pupils who benefited by the radio lessons" might have also been "those who need them least" and "who would suffer least by curtailment of their classroom instruction".[3] Superintendent Johnson received praise for his efforts from university professors and other educators.[8] ImpactPromptly following Chicago's lead, a number of other American communities that experienced polio outbreaks of their own, such as Rochester, New York and Cleveland, were quick to launch radio distance education programs.[14] Seeing potential in the medium of radio to provide educational lessons, the Chicago Board of Education continued producing educational programming. They formed the Chicago Radio Council and would launch their own radio station, WBEZ, in 1943.[15][16][17] Renewed attention during the COVID-19 pandemicChicago's 1937 distance education program received some renewed attention during the COVID-19 pandemic, during parts of which technology-enabled distance learning broadly supplanted in-person instruction. A number of sources mentioned Chicago's 1937 venture with distance education during a viral outbreak as a precursor of sorts to the distance education that has taken place during the COVID-19 pandemic.[3][2][18] References

|