|

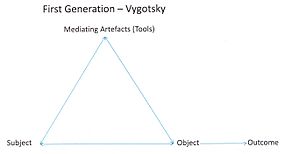

Cultural-historical activity theoryCultural-historical activity theory (CHAT) is a theoretical framework[1] to conceptualize and analyse the relationship between cognition (what people think and feel) and activity (what people do).[2][3][4] The theory was founded by L. S. Vygotsky[5] and Aleksei N. Leontiev, who were part of the cultural-historical school of Russian psychology.[6] The Soviet philosopher of psychology, S.L. Rubinshtein, developed his own variant of activity as a philosophical and psychological theory, independent from Vygotsky's work.[7] Political restrictions in Stalinist Russia had suppressed the cultural-historical psychology – also known as the Vygotsky School – in the mid-thirties. This meant that the core "activity" concept remained confined to the field of psychology. Vygotsky's insight into the dynamics of consciousness was that it is essentially subjective and shaped by the history of each individual's social and cultural experiences.[8] Since the 1990s, CHAT has attracted a growing interest among academics worldwide.[3] Elsewhere CHAT has been described as "a cross-disciplinary framework for studying how humans transform natural and social reality, including themselves, as an ongoing culturally and historically situated, materially and socially mediated process". CHAT explicitly incorporates the mediation of activities by society, which means that it can be used to link concerns normally independently examined by sociologists of education and (social) psychologists.[4][9] Core ideas are: 1) humans act collectively, learn by doing, and communicate in and via actions; 2) humans make, employ, and adapt tools to learn and communicate; and 3) community is central to the process of making and interpreting meaning – and thus to all forms of learning, communicating, and acting.[10][3] The term CHAT was coined by Michael Cole[11] and popularized by Yrjö Engeström[12] to promote the unity of what, by the 1990s, had become a variety of currents harking back to Vygotsky's work.[13][14] Prominent among those currents are Cultural-historical psychology, in use since the 1930s, and Activity theory in use since the 1960s. Historical overviewOrigins: revolutionary RussiaCHAT traces its lineage to dialectical materialism, classical German philosophy,[15][16] and the work of Lev Vygotsky, Aleksei N. Leontiev and Aleksandr Luria, known as "the founding troika"[17] of the cultural-historical approach to Social Psychology. In particular Goethe's romantic science ideas which were later taken up by Hegel. The conceptual meaning of "activity" is rooted in the German word Tätigkeit. Hegel is considered the first philosopher to point out that the development of humans' knowledge is not spiritually given, but developed in history from living and working in natural environments. In a radical departure from the behaviorism and reflexology that dominated much of psychology in the early 1920s, they formulated, in the spirit of Karl Marx's Theses on Feuerbach, the concept of activity, i.e., "artifact-mediated and object-oriented action".[8] By bringing together the notion of history and culture in the understanding of human activity, they were able to transcend the Cartesian dualism between subject and object, internal and external, between people and society, between individual inner consciousness and the outer world of society. At the beginning of and into the mid-20th century, psychology was dominated by schools of thought that ignored real-life processes in psychological functioning (e.g. Gestalt psychology, Behaviorism and Cognitivism (psychology)). Lev Vygotsky, who developed the foundation of cultural-historical psychology based on the concept of mediation, published six books on psychology topics during a working life which spanned only ten years. He died of tuberculosis in 1934 at the age of 37. A.N. Leont'ev worked with Lev Vygotsky and Alexandr Luria from 1924 to 1930, collaborating on the development of a Marxist psychology. Leontiev left Vygotsky's group in Moscow in 1931, to take up a position in Kharkov. There he was joined by local psychologists, including Pyotr Galperin and Pyotr Zinchenko.[18] He continued to work with Vygotsky for some time but, eventually, there was a split, although they continued to communicate with one another on scientific matters.[19] Leontiev returned to Moscow in 1934. Contrary to popular belief, Vygotsky's work was never banned in Stalinist Soviet Russia.[20] In 1950 A.N. Leontiev became the Head of the Psychology Department at the Faculty of Philosophy of the Lomonosov Moscow State University (MGU). This department became an independent Faculty in 1966. He remained there until his death in 1979. Leontiev's formulation of activity theory, post 1962, had become the new "official" basis for Soviet psychology.[21] In the two decades between a thaw in the suppression of scientific enquiry in Russia and the death of the Vygotsky's continuers, contact was made with the West. Developments in the WestMichael Cole, a psychology post-graduate exchange student, arrived in Moscow in 1962 for a one-year stint of research under Alexandr Luria. He was one for the first Westerners to present Luria's and Vygotsky's ideas to an Anglo-Saxon public.[22] This, and a steady flow of books translated from Russian ensured the gradual establishment of a Cultural Psychology base in the west.[4] The earliest books translated into English were Lev Vygotsky's "Thought and Language" (1962), Luria's "Cognitive Development" (1976), Leontiev's Activity, Consciousness, and Personality (1978) and Wertsch's "The Concept of Activity in Soviet Psychology" (1981). Principal among the groups promoting CHAT-related research was Yjrö Engeström's Helsinki-based CRADLE.[23] In 1982, Yrjö Engeström organized an Activity Conference to concentrate on teaching and learning issues. This was followed by the Aarhus (Dk) Conference in 1983 and the Utrecht (Nl) conference in 1984. In October 1986, West Berlin's College of Arts hosted the first ISCAR International Congress on Activity Theory.[24] The second ISCRAT congress took place in 1990. In 1992, ISCRAT became a formal legal organization with its own by-laws in Amsterdam. Other ISCRAT conferences: Rome (1993), Moscow (1995), Aarhus (1998) and Amsterdam (2002), when ISCRAT and the Conference for Socio-Cultural Research merged into ISCAR. From here on, ISCAR organizes an international Congress every three years: Sevilla (Es) 2005; San Diego (USA) 2008; Rome (It) 2011; Sydney (Au) 2014; Quebec, Canada (2017). In recent years, the implications of activity theory in organizational development have been the focus of researchers at the Centre for Activity Theory and Developmental Work Research (CATDWR), now known as CRADLE, at the University of Helsinki, as well as Mike Cole at the Laboratory of Comparative Human Cognition (LCHC) at the University of California San Diego.[25] Three generations of activity theoryDiverse philosophical and psychological sources inform activity theory.[12] In subsequent years, a simplified picture emerged, namely the idea that there are three principal 'stages' or 'generations' of activity theory, or "cultural-historical activity theory (CHAT).[26][27][28][7] 'Generations' do not imply a 'better-worse' value judgment. Each generation illustrates a different aspect. Whilst the first generation built on Vygotsky's notion of mediated action from the individual's perspective, the second generation built on Leont'ev's notion of activity system, with emphasis on the collective. The third generation, which appeared in the mid-nineties, builds on the idea of multiple interacting activity systems focused on a partially shared object, with boundary-crossings between them.[29][30][27] An activity system is a collective in which one or more human actors engage in activity to cyclically transform an object (a raw material or problem) to repeatedly achieve a desired result.[31] First generation – VygotskyThe first generation emerges from Vygotsky's theory of cultural mediation, which was a response to behaviorism's explanation of consciousness, or the development of the human mind, by reducing the human "mind" to atomic components or structures associated with "stimulus – response" (S-R) processes. Vygotsky argued that the relationship between a human subject and an object is never direct but must be sought in society and culture because they evolve historically, rather than evolving in the human brain or individual mind unto itself. Vygotsky saw the past and present as fused within the individual, that the "present is seen in the light of history."[8] His cultural-historical psychology attempted to account for the social origins of language and thinking. To Vygotsky, consciousness emerges from human activity mediated by artifacts (tools) and signs.[8] These artifacts, which can be physical tools such as hammers, ovens, or computers; cultural artifacts, including language; or theoretical artifacts, like algebra or feminist theory, are created and/or transformed in the course of activity, which, in the first generation framework, happens at the individual level.[8]  Semiotic mediation[32] is embodied in Vygotsky's triangular model[8] which features the subject (S), object (O), and mediating artifact.[33] Vygotsky's triangular representation of mediated action attempts to explain human consciousness development in a manner that did not rely on dualistic stimulus–response (S-R) associations. In mediated action the subject, object, and artifact stand in dialectical relationship whereby each affects the other and the activity as a whole.[34][13][8] Vygotsky argued that the use of signs leads to a specific structure of human behavior, which allows the creation of new forms of culturally-based psychological processes – hence the importance of a cultural-historical context. Individuals could no longer be understood without their cultural environment, nor society without the agency of the individuals who use and produce these artifacts. The objects became cultural entities, and action that was oriented towards the objects became key to understanding the human psyche. In the Vygotskyan framework, the unit of analysis is the individual. First-generation activity theory has been used to understand individual behavior by examining the ways in which a person's objectivized actions are culturally mediated. Mediation is a key theoretical idea behind activity: People don't simply use tools and symbol systems; instead, everyday lived experiences are significantly mediated and intermediated by use of tools and symbols systems. Therefore, activity theory helps frame our understanding of such mediation. There is a strong focus on material and symbolic mediation, as well as internalization of external (social, societal, and cultural) forms of mediation. In Vygotskyan psychology, internalization is a theoretical concept that explains how individuals process what they learned through mediated action in the development of individual consciousness.[16] Another important aspect of first generation CHAT is the concept of the zone of proximal development (ZPD)[8] or "the distance between the actual developmental level as determined by independent problem solving and the level of potential development as determined through problem solving under adult guidance or in collaboration with more capable peers".[8] ZPD is the theoretical range of what a performer can do with competent peers and assistance, as compared with what can be accomplished on one's own.[35] Second generation – LeontievWhile Vygotsky formulated practical human activity as the general explanatory category in human psychology, he did not fully clarify its nature. A.N. Leontiev developed the second generation of activity theory, which is a collective model. In Engeström's[12] depiction of second-generation activity, the unit of analysis includes collective motivated activity toward an object, making room for understanding how collective action by social groups mediates activity. Leontiev theorized that activity resulted from the confluence of a human subject, the object of their activity as "the target or content of a thought or action"[36] and the tools (including symbol systems) that mediate the object(ive). He saw activity as tripartite in structure, being composed of unconscious operations on/with tools, conscious but finite actions which are goal-directed, and higher level activities which are object-oriented and driven by motives. Hence, second generation activity theory included community, rules, division of labor and the importance of analyzing their interactions with each other. Rules may be explicit or implicit. Division of labor refers to the explicit and implicit organization of the community involved in the activity. Engeström[12] described Vygotskian psychology as emphasizing the way semiotic and cultural systems mediate human action, whereas Leontiev's second-generation CHAT focused on the mediational effects of the systemic organization of human activity.  In conceptualizing activity as only existing in relation to rules, community and division of labor, Engeström expanded the unit of analysis for studying human behavior from individual activity to a collective activity system. While the unit of analysis, for Vygotsky, is "individual activity" and, for Leontiev, the "collective activity system", for Jean Lave and others working around situated cognition the unit of analysis is "practice", "community of practice", and "participation". Other scholars analyze "the relationships between the individual's psychological development and the development of social systems".[37][38] The activity system includes the social, psychological, cultural and institutional perspectives in the analysis. In this conceptualization, context or activity systems are inherently related to what Engeström argues are the deep-seated material practices and socioeconomic structures of a given culture. These societal dimensions had not been taken sufficiently into account by Vygotsky's, earlier triadic model.[39][40][41] In Leontiev's understanding, thought and cognition were understood as a part of social life – as a part of the means of production and systems of social relations on one hand, and the intentions of individuals in certain social conditions on the other.[10] In the second generation diagram, activity is positioned in the middle, mediation at the top, adding rules, community and division of labor at the bottom. The minimum components of an activity system are: the subject; the object; outcome; mediating instruments/tools/artifacts; rules and signs; community and division of labor. In his example of the 'primeval collective hunt',[42] Leontiev clarifies the difference between an individual action ("the beater frightening game") and a collective activity ("the hunt"). While individuals' actions (frightening game) are different from the overall goal of the activity (hunt), they share the same motive (obtaining food). Operations, on the other hand, are driven by the conditions and tools at hand, i.e. the objective circumstances under which the hunt is taking place. To understand the separate actions of the individuals, one needs to understand the broader motive behind the activity as a whole. This accounts for the three hierarchical levels of human functioning:[12][1][4][39][43] object-related motives drive the collective activity (top); goals drive individual/group action(s) (middle); conditions and tools drive automated operations (lower level).[42][17][26][35] Third generation – Engeström et al.After Vygotsky's foundational work on individuals' higher psychological functions[8] and Leontiev's extension of these insights to collective activity systems,[16] questions of diversity and dialogue between different traditions or perspectives became increasingly serious challenges. The work of Michael Cole and Yrjö Engeström in the 1970s and 1980s brought activity theory to a much wider audience of scholars in Scandinavia and North America.[3] Once the lives and biographies of all the participants and the history of the wider community are taken into account, multiple activity systems needed to be considered, positing, according to Engeström, the need for a "third generation" to "develop conceptual tools to understand dialogue, multiple perspectives, and networks of interacting activity Systems".[33] This larger canvas of active individuals (and researchers) embedded in organizational, political, and discursive practices constitutes a tangible advantage of second- and third-generation CHAT over its earlier Vygotskian ancestor, which focused on mediated action in relative isolation.[4] Third-generation activity theory is the application of Activity Systems Analysis (ASA)[28] in developmental research where investigators take a participatory and interventionist role in the participants' activities and change their experiences.  Engeström's basic activity triangle[12] (which adds rules/norms, intersubjective community relations, and division of labor, as well as multiple activity systems sharing an object) has become the principal third-generation model for analysing individuals and groups.[17] Engeström summarizes the current state of CHAT with five principles:

Learning technologists have used third-generation CHAT as a guiding theoretical framework to understand how technologies are adopted, adapted, and configured through use in complex social situations.[44] Engeström has acknowledged that the third-generation model was limited to analysing 'reasonably well-bounded' systems and that in view of new, often web-based participatory practices a Fourth generation was needed. Informing research and practiceLeontiev and social developmentFrom the 1960s onwards, starting in the global South, and independently from the mainstream European developmental line,[45] Leontiev's core Objective Activity concept[46] has been used in a Social Development context. In the Organization Workshop's Large Group Capacitation-method,[47] objective/ized activity acts as the core causal principle which postulates that, in order to change the mind-set of (large groups of) individuals, we need to start with changes to their activity – and/or to the object that "suggests" their activity.[48] In Leontievian vein, the Organization Workshop is about semiotically mediated activities through which (large groups of) participants learn how to manage themselves and the organizations they create to perform tasks that require complex division of labor.[48] CHAT-inspired research and practice since the 1980sOver the last two decades, CHAT has offered a theoretical lens informing research and practice, in that it posits that learning takes place through collective activities that are purposefully conducted around a common object. Starting from the premise that learning is a social and cultural process that draws on historical achievements, its systems thinking-based perspectives allow insights into the real world.[49][50][33] Change Laboratory (CL)Change Laboratory (CL) is a CHAT-based method for formative intervention in activity systems and for research on their developmental potential as well as processes of expansive learning, collaborative concept-formation, and transformation of practices, elaborated in the mid-nineties[51][52] by the Finnish Developmental Work Research (DWR) group, which became CRADLE in 2008.[33] The CL method relies on collaboration between practitioners of the activity being analyzed and transformed, and academic researchers or interventionists supporting and facilitating collective developmental processes.[33] Engeström developed a theory of expansive learning, which "begins with individual subjects questioning accepted practices, and it gradually expands into a collective movement or institution. The theory enables a "longitudinal and rich analysis of inter-organizational learning by using observational as well as interventionist designs in studies of work and organization".[53][12] From this, the foundation of an interventionist research approach at DWR[33] was elaborated in the 1980s, and developed further in the 1990s as an intervention method now known as Change Laboratory.[54] CL interventions are used both to study the conditions of change and to help those working in organizations to develop their work, drawing on participant observation, interviews, and the recording and videotaping of meetings and work practices. Initially, with the help of an external interventionist, the first stimulus that is beyond the actors' present capabilities, is produced in the Change Laboratory by collecting first-hand empirical data on problematic aspects of the activity. This data may comprise difficult client cases, descriptions of recurrent disturbances and ruptures in the process of producing the outcome. Steps in the CL process: Step 1 Questioning; Step 2 Analysis; Step 3 Modeling; Step 4 Examining; Step 5 Implementing; Step 6 Reflecting; Step 7 Consolidating. These seven action steps for increased understanding are described by Engeström as expansive learning, or phases of an outwardly expanding spiral,[2] while multiple kinds of actions can take place at any time.[55] The phases of the model simply allow for the identification and analysis of the dominant action type during a particular period of time. These learning actions are provoked by contradictions.[16] Contradictions are not simply conflicts or problems, but are "historically accumulating structural tensions within and between activity systems".[33] CL is used by a team or work unit or by collaborating partners across the organizational boundaries, initially with the help of an interventionist-researcher.[50][54] The CL method has been used in agricultural contexts,[56] educational and media settings,[57] health care[58] and learning support.[2][52] Activity systems analysis (ASA)Activity systems analysis is a CHAT-based method that uses Activity Theory concepts such as mediated action, goal-directed activity and dialectical relationship between the individual and environment for understanding human activity in real-world situations with data collection, analysis, and presentation methods that address the complexities of human activity in natural settings aimed to advance both theory and practice.[59][60][12] It is based on Vygotsky's concept of mediated action and captures human activity in a triangle model that includes the subject, tool, object, rule, community, and division of labor.[12] Subjects are participants in an activity, motivated toward a purpose or attainment of the object. The object can be the goal of an activity, the subject's motives for participating in an activity, and the material products that subjects gain through an activity. Tools are socially shared cognitive and material resources that subjects can use to attain the object. Informal or formal rules regulate the subject's participation while engaging in an activity. The community is the group or organization to which subjects belong. The division of labor is the shared participation responsibilities in the activity determined by the community. Finally, the outcome is the consequences that the subject faces due to actions driven by the object. These outcomes can encourage or hinder the subject's participation in future activities. In Part 2 of her video "Using Activity Theory to understand human behaviour", van der Riet 2010 shows how activity theory is applied to the problem of behavior change and HIV and AIDs (in South Africa). The video focuses on sexual activity as the activity of the system and illustrates how an activity system analysis, through a historical and current account of the activity, provides a way of understanding the lack of behavior change in response to HIV and AIDS. The book Activity Systems Analysis Methods[61] describes seven ASA case studies which fall "into four distinct work clusters. These clusters include works that help (a) understand developmental work research (DWR), (b) describe real-world learning situations, (c) design human-computer interaction systems, and (d) plan solutions to complicated work-based problems". Other uses of ASA include summarizing organizational change;[60] identifying guidelines for designing constructivist learning environments;[62] identifying contradictions and tensions that shape developments in educational settings;[14][28] demonstrating historical developments in organizational learning,[63] and evaluating K–12 school and university partnership relations.[64] Human–computer interaction (HCI)When human-computer interaction (HCI) first appeared as a separate field of study in the early 1980s, HCI adopted the information processing paradigm of computer science as the model for human cognition, predicated on prevalent cognitive psychology criteria, which did not account for individuals' interests, needs and frustrations involved, nor that the technology depends on the social and dynamic contexts in which it takes place.[3][1] Adopting a CHAT theoretical perspective carries implications for understanding how people use interactive technologies: for example, a computer is typically an object of activity rather than a mediating artefact means that people interact with the world through computers, rather than with computer 'objects'.[3][65][66] Since the 1980s, a number of diverse methodologies outlining techniques for human–computer interaction design have emerged. Most design methodologies stem from a model for how users, designers, and technical systems interact.[3][1] Systemic-structural activity theory (SSAT)SSAT builds on the general theory of activity to provide an effective basis for both experimental and analytic methods of studying human performance, using developed units of analysis.[67] SSAT approaches cognition both as a process and as a structured system of actions or other functional information-processing units, developing a taxonomy of human activity through the use of structurally organized units of analysis. The systemic-structural approach to activity design and analysis involves identifying the available means of work, tools and objects; their relationship with possible strategies of work activity; existing constraints on activity performance; social norms and rules; possible stages of object transformation; and changes in the structure of activity during skills acquisition.This method is demonstrated by applying it to the study of a human–computer interaction task.[68] FutureEvolving field of studyCHAT offers a philosophical and cross-disciplinary perspective for analyzing human practices as development processes in which both individual and social levels are interlinked, as well as interactions and boundary-crossings[30] between activity systems.[1][69] Crossing boundaries involves "encountering difference, entering into unfamiliar territory, requiring cognitive retooling".[70] More recently, the focus of studies of organizational learning has increasingly shifted away from learning within single organizations or organizational units, towards learning in multi‐organizational or inter‐organizational networks, as well as to the exploration of interactions in their social contexts, multiple contexts and cultures, and the dynamics and development of particular activities. This shift has generated such concepts as "networks of learning",[16] "networked learning",[53] coworking,[71] and knotworking.[72][31][73] Industry has seen growth in nonemployer firms (NEFs) due to changes in long-term employment trends and developments in mobile technology[74] which have led to more work from remote locations, more distance collaboration, and more work organized around temporary projects.[75] Developments such as these and new forms of social production or commons-based peer production like open source software development and cultural production in peer-to-peer (P2P) networks have become a key focus in Engeström's work.[73][76] Social production processes are simultaneous, multi-directional and often reciprocal. The density and complexity of these processes blur distinctions between process and structure. The object of the activity is unstable, resists control and standardization, and requires rapid integration of expertise from various locations and traditions.[71] "Fourth generation"The rapid rise of new forms of activities characterised by web-based social and participatory practices phenomena such as distributed workforce and the dominance of knowledge work, prompts a rethink of the third-generation model, bringing a need for a fourth generation activity system model.[71][75][2] Fourth-Generation (4GAT) analysis should allow better examination of how activity networks interact, interpenetrate, and contradict each other. People "working alone together" may illuminate other examples of distributed, interorganizational, collaborative knowledge work.[75] In fourth generation CHAT, the object(ive) will typically comprise multiple perspectives and contexts and be inherently transient; collaborations between actors are likely to be temporary, with multiple boundary crossings between interrelated activities.[30] Fourth-generation activity theorists have specifically developed activity theory to better accommodate Castells's[74] (and others') insights into how work organization has shifted in the network society. Hence, they will focus less on the workings of individual activity systems (often represented by triangles) and more on the interactions across activity systems functioning in networks.[75][71] See also

References

Works cited

Further reading

External links

|