|

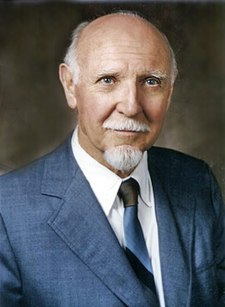

Raymond Cattell

Raymond Bernard Cattell (20 March 1905 – 2 February 1998) was a British-American psychologist, known for his psychometric research into intrapersonal psychological structure.[1][2] His work also explored the basic dimensions of personality and temperament, the range of cognitive abilities, the dynamic dimensions of motivation and emotion, the clinical dimensions of abnormal personality, patterns of group syntality and social behavior,[3] applications of personality research to psychotherapy and learning theory,[4] predictors of creativity and achievement,[5] and many multivariate research methods[6] including the refinement of factor analytic methods for exploring and measuring these domains.[7][8] Cattell authored, co-authored, or edited almost 60 scholarly books, more than 500 research articles, and over 30 standardized psychometric tests, questionnaires, and rating scales.[9][10] According to a widely cited ranking, Cattell was the 16th most eminent,[11] 7th most cited in the scientific journal literature,[12] and among the most productive psychologists of the 20th century.[13] Cattell was an early proponent of using factor analytic methods instead of what he called "subjective verbal theorizing" to explore empirically the basic dimensions of personality, motivation, and cognitive abilities. One of the results of Cattell's application of factor analysis was his discovery of 16 separate primary trait factors within the normal personality sphere (based on the trait lexicon).[14] He called these factors "source traits".[15] This theory of personality factors and the self-report instrument used to measure them are known respectively as the 16 personality factor model and the 16PF Questionnaire (16PF).[16] Cattell also undertook a series of empirical studies into the basic dimensions of other psychological domains: intelligence,[17] motivation,[18] career assessment and vocational interests.[19] Cattell theorized the existence of fluid and crystallized intelligence to explain human cognitive ability,[20] investigated changes in Gf and Gc over the lifespan,[21] and constructed the Culture Fair Intelligence Test to minimize the bias of written language and cultural background in intelligence testing.[22] Innovations and accomplishmentsCattell's research was mainly in personality, abilities, motivations, and innovative multivariate research methods and statistical analysis (especially his many refinements to exploratory factor analytic methodology).[8][23] In his personality research, he is best remembered for his factor-analytically derived 16-factor model of normal personality structure,[10] arguing for this model over Eysenck's simpler higher-order 3-factor model, and constructing measures of these primary factors in the form of the 16PF Questionnaire (and its downward extensions: HSPQ, and CPQ, respectively).[15] He was the first to propose a hierarchical, multi-level model of personality with the many basic primary factors at the first level and the fewer, broader, "second-order" factors at a higher stratum of personality organization.[24] These "global trait" constructs are the precursors of the currently popular Big Five (FFM) model of personality.[25][26][27][28] Cattell's research led to further advances, such as distinguishing between state and trait measures (e.g., state-trait anxiety),[29] ranging on a continuum from immediate transitory emotional states, through longer-acting mood states, dynamic motivational traits, and also relatively enduring personality traits.[30] Cattell also conducted empirical studies into developmental changes in personality trait constructs across the lifespan.[31] In the cognitive abilities domain, Cattell researched a wide range of abilities, but is best known for the distinction between fluid and crystallized intelligence.[20] He distinguished between the abstract, adaptive, biologically-influenced cognitive abilities that he called "fluid intelligence" and the applied, experience-based and learning-enhanced ability that he called "crystallized intelligence." Thus, for example, a mechanic who has worked on airplane engines for 30 years might have a huge amount of "crystallized" knowledge about the workings of these engines, while a new young engineer with more "fluid intelligence" might focus more on the theory of engine functioning, these two types of abilities might complement each other and work together toward achieving a goal. As a foundation for this distinction, Cattell developed the investment-model of ability, arguing that crystallized ability emerged from the investment of fluid ability in a particular topic of knowledge. He contributed to cognitive epidemiology with his theory that crystallized knowledge, while more applied, could be maintained or even increase after fluid ability begins to decline with age, a concept used in the National Adult Reading Test (NART). Cattell constructed a number of ability tests, including the Comprehensive Ability Battery (CAB) that provides measures of 20 primary abilities,[32] and the Culture Fair Intelligence Test (CFIT) which was designed to provide a completely non-verbal measure of intelligence like that now seen in the Raven's. The Culture Fair Intelligence Scales were intended to minimize the influence of cultural or educational background on the results of intelligence tests.[33] In regard to statistical methodology, in 1960 Cattell founded the Society of Multivariate Experimental Psychology (SMEP), and its journal Multivariate Behavioral Research, in order to bring together, encourage, and support scientists interested in multi-variate research.[34] He was an early and frequent user of factor analysis (a statistical procedure for finding underlying factors in data). Cattell also developed new factor analytic techniques, for example, by inventing the scree test, which uses the curve of latent roots to judge the optimal number of factors to extract.[35] He also developed a new factor analysis rotation procedure—the "Procrustes" or non-orthogonal rotation, designed to let the data itself determine the best location of factors, rather than requiring orthogonal factors. Additional contributions include the Coefficient of Profile Similarity (taking account of shape, scatter, and level of two score profiles); P-technique factor analysis based on repeated measurements of a single individual (sampling of variables, rather than sampling of persons); dR-technique factor analysis for elucidating change dimensions (including transitory emotional states, and longer-lasting mood states); the Taxonome program for ascertaining the number and contents of clusters in a data set; the Rotoplot program for attaining maximum simple structure factor pattern solutions.[8] As well, he put forward the Dynamic Calculus for assessing interests and motivation,[18][36] the Basic Data Relations Box (assessing dimensions of experimental designs),[37] the group syntality construct ("personality" of a group),[38] the triadic theory of cognitive abilities,[39] the Ability Dimension Analysis Chart (ADAC),[40] and Multiple Abstract Variance Analysis (MAVA), with "specification equations" to embody genetic and environmental variables and their interactions.[41] As Lee J. Cronbach at Stanford University stated:

BiographyEnglandRaymond Cattell was born on 20 March 1905 in Hill Top, West Bromwich, a small town in England near Birmingham where his father's family was involved in inventing new parts for engines, automobiles and other machines. Thus, his growing up years were a time when great technological and scientific ideas and advances were taking place and this greatly influenced his perspective on how a few people could actually make a difference in the world. He wrote: "1905 was a felicitous year in which to be born. The airplane was just a year old. The Curies and Rutherford in that year penetrated the heart of the atom and the mystery of its radiations, Alfred Binet launched the first intelligence test, and Einstein, the theory of relativity.[1][42] When Cattell was about five years old, his family moved to Torquay, Devon, in the south-west of England, where he grew up with strong interests in science and spent a lot of time sailing around the coastline. He was the first of his family (and the only one in his generation) to attend university: in 1921, he was awarded a scholarship to study chemistry at King's College, London, where he obtained a BSc (Hons) degree with 1st-class honors at age 19 years.[1][43] While studying physics and chemistry at university he learned from influential people in many other fields, who visited or lived in London. He writes:

As he observed first-hand the terrible destruction and suffering after World War I, Cattell was increasingly attracted to the idea of applying the tools of science to the serious human problems that he saw around him. He stated that in the cultural upheaval after WWI, he felt that his laboratory table had begun to seem too small and the world's problems so vast.[44] Thus, he decided to change his field of study and pursue a PhD in psychology at King's College, London, which he received in 1929. The title of his PhD dissertation was "The Subjective Character of Cognition and Pre-Sensational Development of Perception". His PhD advisor at King's College, London, was Francis Aveling, D.D., D.Sc., PhD, D.Litt., who was also President of the British Psychological Society from 1926 until 1929.[1][45][46][47][48] In 1939, Cattell was honored for his outstanding contributions to psychological research with conferral of the prestigious higher doctorate – D.Sc. from the University of London.[34] While working on his PhD, Cattell had accepted a position teaching and counseling in the Department of Education at Exeter University.[1] He ultimately found this disappointing because there was limited opportunity to conduct research.[1] Cattell did his graduate work with Charles Spearman, the English psychologist and statistician who is famous for his pioneering work on assessing intelligence, including the development of the idea of a general factor of intelligence termed g.[49] During his three years at Exeter, Cattell courted and married Monica Rogers, whom he had known since his boyhood in Devon and they had a son together. She left him about four years later.[50] Soon afterward he moved to Leicester where he organized one of England's first child guidance clinics. It was also in this time period that he finished his first book "Under Sail Through Red Devon," which described his many adventures sailing around the coastline and estuaries of South Devon and Dartmoor.[44] United StatesIn 1937, Cattell left England and moved to the United States when he was invited by Edward Thorndike to come to Columbia University. When the G. Stanley Hall professorship in psychology became available at Clark University in 1938, Cattell was recommended by Thorndike and was appointed to the position. However, he conducted little research there and was "continually depressed."[50] Cattell was invited by Gordon Allport to join the Harvard University faculty in 1941. While at Harvard he began some of the research in personality that would become the foundation for much of his later scientific work.[1] During World War II, Cattell served as a civilian consultant to the U.S. government researching and developing tests for selecting officers in the armed forces. Cattell returned to teaching at Harvard and married Alberta Karen Schuettler, a PhD student in mathematics at Radcliffe College. Over the years, she worked with Cattell on many aspects of his research, writing, and test development. They had three daughters and a son.[44] They divorced in 1980.[50] Herbert Woodrow, professor of psychology at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, was searching for someone with a background in multivariate methods to establish a research laboratory. Cattell was invited to assume this position in 1945. With this newly created research professorship in psychology, he was able to obtain sufficient grant support for two PhD associates, four graduate research assistants, and clerical assistance.[44] One reason that Cattell moved to the University of Illinois was because the first electronic computer built and owned entirely by a US educational institution – "Illinois Automatic Computer" – was being developed there, which made it possible for him to complete large-scale factor analyses. Cattell founded the Laboratory of Personality Assessment and Group Behavior.[44] In 1949, he and his wife founded the Institute for Personality and Ability Testing (IPAT). Karen Cattell served as director of IPAT until 1993. Cattell remained in the Illinois research professorship until he reached the university's mandatory retirement age in 1973. A few years after he retired from the University of Illinois he built a home in Boulder, Colorado, where he wrote and published the results of a variety of research projects that had been left unfinished in Illinois.[1] In 1977, Cattell moved to Hawaii, largely because of his love of the ocean and sailing. He continued his career as a part-time professor and adviser at the University of Hawaii. He also served as adjunct faculty of the Hawaii School of Professional Psychology. After settling in Hawaii he married Heather Birkett, a clinical psychologist, who later carried out extensive research using the 16PF and other tests.[51][52] During the last two decades of his life in Hawaii, Cattell continued to publish a variety of scientific articles, as well as books on motivation, the scientific use of factor analysis, two volumes of personality and learning theory, the inheritance of personality, and co-edited a book on functional psychological testing, as well as a complete revision of his highly renowned Handbook of Multivariate Experimental Psychology.[37] Cattell and Heather Birkett Cattell lived on a lagoon in the southeast corner of Oahu where he kept a small sailing boat. Around 1990, he had to give up his sailing career because of navigational challenges resulting from old age. He died at home in Honolulu on 2 February 1998, at age 92 years. He is buried in the Valley of the Temples on a hillside overlooking the sea.[53] His will provided for his remaining funds to build a school for underprivileged children in Cambodia.[54] He was an agnostic.[1] Scientific orientationWhen Cattell began his career in psychology in the 1920s, he felt that the domain of personality was dominated by speculative ideas that were largely intuitive with little/no empirical research basis.[10] Cattell accepted E.L. Thorndike's empiricist viewpoint that "If something actually did exist, it existed in some amount and hence could be measured.".[55] Cattell found that constructs used by early psychological theorists tended to be somewhat subjective and poorly defined. For example, after examining over 400 published papers on the topic of "anxiety" in 1965, Cattell stated: "The studies showed so many fundamentally different meanings used for anxiety and different ways of measuring it, that the studies could not even be integrated."[56] Early personality theorists tended to provide little objective evidence or research bases for their theories. Cattell wanted psychology to become more like other sciences, whereby a theory could be tested in an objective way that could be understood and replicated by others. In Cattell's words:

Emeritus Professor Arthur B. Sweney, an expert in psychometric test construction,[58] summed up Cattell's methodology:

Also, according to Sheehy (2004, p. 62),

In 1994, Cattell was one of 52 signatories of "Mainstream Science on Intelligence,"[60] an editorial written by Linda Gottfredson and published in the Wall Street Journal. In the letter the signers, some of whom were intelligence researchers, defended the publication of the book The Bell Curve. There was sharp pushback on the letter, with a number of signers (not Cattell) having received funding from white supremacist organizations. His works can be categorized or defined as part of cognitive psychology, due to his nature to measure every psychological aspect especially personality aspect. Multivariate researchRather than pursue a "univariate" research approach to psychology, studying the effect that a single variable (such as "dominance") might have on another variable (such as "decision-making"), Cattell pioneered the use of multivariate experimental psychology (the analysis of several variables simultaneously).[6][37][59] He believed that behavioral dimensions were too complex and interactive to fully understand variables in isolation. The classical univariate approach required bringing the individual into an artificial laboratory situation and measuring the effect of one particular variable on another – also known as the "bivariate" approach, while the multivariate approach allowed psychologists to study the whole person and their unique combination of traits within a natural environmental context. Multivariate experimental research designs and multivariate statistical analyses allowed for the study of "real-life" situations (e.g., depression, divorce, loss) that could not be manipulated in an artificial laboratory environment.[34] Cattell applied multivariate research methods across several intrapersonal psychological domains: the trait constructs (both normal and abnormal) of personality, motivational or dynamic traits, emotional and mood states, as well as the diverse array of cognitive abilities.[14] In each of these domains, he considered there must be a finite number of basic, unitary dimensions that could be identified empirically. He drew a comparison between these fundamental, underlying (source) traits and the basic dimensions of the physical world that were discovered and presented, for example, in the periodic table of chemical elements.[15] In 1960, Cattell organized and convened an international symposium to increase communication and cooperation among researchers who were using multivariate statistics to study human behavior. This resulted in the foundation of the Society of Multivariate Experimental Psychology (SMEP) and its flagship journal, Multivariate Behavioral Research. He brought many researchers from Europe, Asia, Africa, Australia, and South America to work in his lab at the University of Illinois.[34] Many of his books involving multivariate experimental research were written in collaboration with notable colleagues.[61] Factor analysisCattell noted that in the hard sciences such as chemistry, physics, astronomy, as well as in medical science, unsubstantiated theories were historically widespread until new instruments were developed to improve scientific observation and measurement. In the 1920s, Cattell worked with Charles Spearman who was developing the new statistical technique of factor analysis in his effort to understand the basic dimensions and structure of human abilities. Factor analysis became a powerful tool to help uncover the basic dimensions underlying a confusing array of surface variables within a particular domain.[8] Factor analysis was built upon the earlier development of the correlation coefficient, which provides a numerical estimate of the degree to which variables are "co-related". For example, if "frequency of exercise" and "blood pressure level" were measured on a large group of people, then intercorrelating these two variables would provide a quantitative estimate of the degree to which "exercise" and "blood pressure" are directly related to each other. Factor analysis performs complex calculations on the correlation coefficients among the variables within a particular domain (such as cognitive ability or personality trait constructs) to determine the basic, unitary factors underlying the particular domain.[62] While working at the University of London with Spearman exploring the number and nature of human abilities, Cattell postulated that factor analysis could be applied to other areas beyond the domain of abilities. In particular, Cattell was interested in exploring the basic taxonomic dimensions and structure of human personality.[14] He believed that if exploratory factor analysis were applied to a wide range of measures of interpersonal functioning, the basic dimensions within the domain of social behavior could be identified. Thus, factor analysis could be used to discover the fundamental dimensions underlying the large number of surface behaviors, thereby facilitating more effective research. As noted above, Cattell made many important innovative contributions to factor analytic methodology, including the Scree Test to estimate the optimal number of factors to extract,[35] the "Procrustes" oblique rotation strategy, the Coefficient of Profile Similarity, P-technique factor analysis, dR-technique factor analysis, the Taxonome program, as well the Rotoplot program for attaining maximum simple structure solutions.[8] In addition, many eminent researchers received their grounding in factor analytic methodology under the guidance of Cattell, including Richard Gorsuch, an authority on exploratory factor analytic methods.[63] Personality theoryIn order to apply factor analysis to personality, Cattell believed it was necessary to sample the widest possible range of variables. He specified three kinds of data for comprehensive sampling, to capture the full range of personality dimensions:

In order for a personality dimension to be called "fundamental and unitary," Cattell believed that it needed to be found in factor analyses of data from all three of these measurement domains. Thus, Cattell constructed measures of a wide range of personality traits in each medium (L-data; Q-data; T-data). He then conducted a programmatic series of factor analyses on the data derived from each of the three measurement media in order to elucidate the dimensionality of human personality structure.[10] With the help of many colleagues, Cattell's factor-analytic studies[8] continued over several decades, eventually finding at least 16 primary trait factors underlying human personality (comprising 15 personality dimensions and one cognitive ability dimension: Factor B in the 16PF). He decided to name these traits with letters (A, B, C, D, E...) in order to avoid misnaming these newly discovered dimensions, or inviting confusion with existing vocabulary and concepts. Factor-analytic studies conducted by many researchers in diverse cultures around the world have provided substantial support for the validity of these 16 trait dimensions.[64] In order to measure these trait constructs across different age ranges, Cattell constructed (Q-data) instruments that included the Sixteen Personality Factor Questionnaire (16PF) for adults, the High School Personality Questionnaire (HSPQ) – now named the Adolescent Personality Questionnaire (APQ), and the Children's Personality Questionnaire (CPQ).[65] Cattell also constructed the (T-data) Objective Analytic Battery (OAB) that provided measures of the 10 largest personality trait factors extracted factor analytically,[66][67] as well as objective (T-data) measures of dynamic trait constructs such as the Motivation Analysis Test (MAT), the School Motivation Analysis Test (SMAT), and the Children's Motivation Analysis Test (CMAT).[18][68] In order to measure trait constructs within the abnormal personality sphere, Cattell constructed the Clinical Analysis Questionnaire (CAQ)[69][70] Part 1 of the CAQ measures the 16PF factors, While Part 2 measures an additional 12 abnormal (psychopathological) personality trait dimensions. The CAQ was later re-badged as the PsychEval Personality Questionnaire (PEPQ).[71][72] Also within the broadly conceptualized personality domain, Cattell constructed measures of mood states and transitory emotional states, including the Eight State Questionnaire (8SQ)[73][74] In addition, Cattell was at the forefront in constructing the Central Trait-State Kit.[75][76] From the very beginning of his academic career, Cattell reasoned that, as in other scientific domains like intelligence, there might be an additional, higher level of organization within personality which would provide a structure for the many primary traits. When he factor analyzed the intercorrelations of the 16 primary trait measures themselves, he found no fewer than five "second-order" or "global factors", now commonly known as the Big Five.[25][27][28] These second-stratum or "global traits" are conceptualized as broad, overarching domains of behavior, which provide meaning and structure for the primary traits. For example, the "global trait" Extraversion has emerged from factor-analytic results comprising the five primary trait factors that are interpersonal in focus.[77] Thus, "global" Extraversion is fundamentally defined by the primary traits that are grouped together factor analytically, and, moving in the opposite direction, the second-order Extraversion factor gives conceptual meaning and structure to these primary traits, identifying their focus and function in human personality. These two levels of personality structure can provide an integrated understanding of the whole person, with the "global traits" giving an overview of the individual's functioning in a broad-brush way, and the more-specific primary trait scores providing an in-depth, detailed picture of the individual's unique trait combinations (Cattell's "Depth Psychometry" p. 71).[4] Research into the 16PF personality factors has shown these constructs to be useful in understanding and predicting a wide range of real life behaviors.[78][79] Thus, the 16 primary trait measures plus the five major second-stratum factors have been used in educational settings to study and predict achievement motivation, learning or cognitive style, creativity, and compatible career choices; in work or employment settings to predict leadership style, interpersonal skills, creativity, conscientiousness, stress-management, and accident-proneness; in medical settings to predict heart attack proneness, pain management variables, likely compliance with medical instructions, or recovery pattern from burns or organ transplants; in clinical settings to predict self-esteem, interpersonal needs, frustration tolerance, and openness to change; and, in research settings to predict a wide range of behavioral proclivities such as aggression, conformity, and authoritarianism.[80] Cattell's programmatic multivariate research which extended from the 1940s through the 70's[81][82][83] resulted in several books that have been widely recognized as identifying fundamental taxonomic dimensions of human personality and motivation and their organizing principles:

The books listed above document a programmatic series of empirical research studies based on quantitative personality data derived from objective tests (T-data), from self-report questionnaires (Q-data), and from observer ratings (L-data). They present a theory of personality development over the human life span, including effects on the individual's behavior from family, social, cultural, biological, and genetic influences, as well as influences from the domains of motivation and ability.[84] As Hans Eysenck at the Institute of Psychiatry, London remarked:

He was a controversial figure due in part to his friendships with, and intellectual respect for, white supremacists and neo-Nazis.[50] Views on race and eugenics

William H. Tucker[86][50] and Barry Mehler[87][88] have criticized Cattell based on his writings about evolution and political systems. They argue that Cattell adhered to a mixture of eugenics and a new religion of his devising which he eventually named Beyondism and proposed as "a new morality from science". Tucker notes that Cattell thanked the prominent neo-Nazi and white supremacist ideologues Roger Pearson, Wilmot Robertson, and Revilo P. Oliver in the preface to his Beyondism, and that a Beyondist newsletter with which Cattell was involved favorably reviewed Robertson's book The Ethnostate. Cattell claimed that a diversity of cultural groups was necessary to allow that evolution. He speculated about natural selection based on both the separation of groups and also the restriction of "external" assistance to "failing" groups from "successful" ones. This included advocating for "educational and voluntary birth control measures"—i.e., by separating groups and limiting excessive growth of failing groups.[89] John Gillis argued in his biography of Cattell that, although some of Cattell's views were controversial, Tucker and Mehler exaggerated and misrepresented his views by taking quotes out of context and referring to outdated writings. Gillis maintained that Cattell was not friends with white supremacists and described Hitler's ideas as "lunacy."[1] In 1997, Cattell was chosen by the American Psychological Association (APA) for its "Gold Medal Award for Lifetime Achievement in the Science of Psychology." Before the medal was presented, Mehler launched a publicity campaign against Cattell through his nonprofit foundation ISAR,[90] accusing Cattell of being sympathetic to racist and fascist ideas.[91] Mehler claimed that "it is unconscionable to honor this man whose work helps to dignify the most destructive political ideas of the twentieth century". A blue-ribbon committee was convened by the APA to investigate the legitimacy of the charges. Before the committee reached a decision, Cattell issued an open letter to the committee saying "I believe in equal opportunity for all individuals, and I abhor racism and discrimination based on race. Any other belief would be antithetical to my life's work" and saying that "it is unfortunate that the APA announcement ... has brought misguided critics' statements a great deal of publicity."[92] Cattell refused the award, withdrawing his name from consideration, and the committee was disbanded. Cattell died months later at the age of 92. In 1984, Cattell said that: "The only reasonable thing is to be noncommittal on the race question – that's not the central issue, and it would be a great mistake to be sidetracked into all the emotional upsets that go on in discussions of racial differences. We should be quite careful to dissociate eugenics from it – eugenics' real concern should be with individual differences."[13] Richard L. Gorsuch (1997) wrote (in a letter to the American Psychological Foundation, para. 4) that: "The charge of racism is 180 degrees off track. [Cattell] was the first one to challenge the racial bias in tests and to attempt to reduce that problem."[13] Selected publicationsRaymond Cattell's papers and books are the 7th most highly referenced in peer-reviewed psychology journals over the past century.[12] Some of his most cited publications are:[93]

Comprehensive list of Cattell's booksSee also

References

External linksWikiquote has quotations related to Raymond Cattell.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||