|

Coat of arms of the Hauteville family

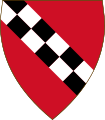

The Hauteville coat of arms is the coat of arms by which the Siculo-Norman dynasty of Hauteville, founder of the Kingdom of Sicily and protagonist of the historical events of southern Italy during the 11th and 12th centuries, is represented. The actual use of a coat of arms by the lineage that had Tancred as its progenitor, however, is not an assumption that is undoubtedly proven or universally agreed upon. There are various reconstructions of the coat of arms, which the various authors have associated with the Hauteville family; the azure insignia with a bend chequy in argent and gules of two rows of tiles has been attested as the most widespread and most accepted representation. The bend chequyOrigin of the coat of arms and significanceThe origin of the coat of arms of the House of Hauteville is uncertain and debated, since there are allegedly no documents or historical evidence to date with certainty its introduction, as well as its actual use by the Siculo-Norman monarchs; according to some studies, the Hauteville coat of arms would be one "attributed" to the dynasty only in later times.[4] This thesis, however, is countered by the reconstructions of some historians, such as Giovanni Antonio Summonte, Agostino Inveges and Giuseppe Sancetta.  Between 1601 and 1602, the four books (the last two posthumously) of the original edition of the Historia della Città e Regno di Napoli, by the Neapolitan historian Giovanni Antonio Summonte, were published. In the following decades and up to the middle of the following century, several reprints were made, as well as expanded editions by other authors, the most widespread being that of 1675. In his monumental work, Summonte writes that Roger II, first king of Sicily, "bore as an insignia a duplicate stripe, divided into five parts, that is, five red, and five silver, which descends from the right side to the left side sideways, placed on an azure field, as did all the Normans his predecessors." In the opinion of the Neapolitan historian, this symbol would signify "an invincible spirit in acquiring supremacy."[2]

A similar but more articulate thesis was made by the Sicilian historian Agostino Inveges, in the third volume of his Annali della felice città di Palermo, prima sedia, corona del Re, e Capo del Regno di Sicilia, a work that was printed between 1649 and 1651. In the views of Inveges, who took up the theses of Giuseppe Sancetta, the Hauteville adopted the new coat of arms, abandoning the one with the two lions of the Duchy of Normandy. The monarchs were to be endowed with a coat of arms "with two stripes, or as Sancetta says: with two bends sinister, chequy gules and argent on a azure field: as is seen in three very ancient wooden plaques hung in the Cathedral of Palermo above the Royal porphyry tombs of King Roger, and of the Empress Constance his daughter [...]".[1]

Less clear, in Inveges' opinion, is the identification of the initiator of the adoption of the new coat of arms. The Sicilian historian advances the hypothesis that the coat of arms was introduced at the time of Roger II, in conjunction with the coronation of 1129;[1] when, without approval from Pope Honorius II, Roger wished to obtain publicly, from an assembly of notables, both lay and religious, from both Sicily and his continental states, the recognition of his sovereign authority.[1][6] To ground his position, Inveges resorts to complex heraldic reasoning:

Analysis of the coat of arms Summonte interprets and explains the Hauteville coat of arms by providing a meaning of the coat of arms in its entirety, understood as the result of the combination of the three tinctures that characterize it: the insignia of the dynasty, therefore, "as composed of two principal colors, and of silver metal, signify nothing but an invincible spirit in acquiring supremacy." In contrast, the analysis of the coat of arms presented by Inveges "breaks down" the coat of arms, examining, disjointly, the heraldic ordinary and its individual tinctures and the field. It seems obvious that his remarks cannot disregard the heraldic charge that characterizes the coat of arms, namely the stripe: the latter, writes the Sicilian historian, "is an insignia of war, & ornament of a Soldier." As reported by Marco Antonio Ginanni, an intellectual and heraldist, author of L'arte del blasone dichiarata per alfabeto, "the stripe represents the baldric, that is, the pendant of the Sword, and is a sign of military honors, and dignity."[7] In his Heraldic-Chivalric Encyclopedia, the heraldist and genealogist Goffredo di Crollalanza endorses Ginanni's interpretation and, with an explicit reference to the figure of the "ancient knights," points out that the stripe "was by heraldry placed among the honorable ordinaries as a sign of military honors and dignities" (adding, in a second line, that the stripe could also represent the scarf worn over the shoulder in military circles).[8] The reference to the Hauteville warriors' and condottieri's skills is not limited to the stripe as such, but extends to its being checkered. Crollalanza reports that the chequy, one of the "noblest and most ancient figures of the blazon," is closely connected to the game of chess and strategy: it represents, like the chessboard, the battlefield and, also, an army deployed in combat, which is why those who have demonstrated their valor in war, that is, their skills as military strategists, boast of it. In Crollalanza's opinion, the introduction of the chequy in heraldry, more likely than other hypotheses, would have precisely a Gothic or Norman origin, since, reports the author of the Heraldic-Chivalric Encyclopedia, it was the Normans who introduced the chequy flags in Normandy, England, Apulia and Sicily.[9]  As for the tinctures, Inveges attributes very specific meanings to them. First and foremost, the Sicilian historian associates, with silver, the wealth of the Kingdom. Certainly, as a metal, silver constitutes, after gold, "the most valuable hue of the blazon." This tincture, however, as Crollalanza reports, symbolizes a plurality of concepts and virtues, such as: skill, clemency, faith, temperance, integrity, truth and purity; but it is also a symbol of dignity and nobility.[10] Red, on the other hand, Inveges continues, represents royal purple: it is no coincidence that this tincture is generally considered "the noblest color of blazon." As for its symbolism, red, in addition to referring to the idea of nobility, instinctively refers to blood and, more specifically, to the shedding of blood in battle. Thus, concepts related to war and combat are associated with it, such as valor, daring, and dominance, but also the desire for revenge, cruelty, and anger. Among the virtues attributable to red, on the other hand, are found fortitude, magnanimity and justice.[11] Coming to the blue of the field, finally, Inveges believes that it represents "the toil of arms, and 'the ordeal of war.'" In French heraldry, azure "is considered as the noblest and most valuable tincture, such as the one that appears on the escutcheon of the royal house, so much so that it is placed before gold itself, although it is not from metal." The symbolism attached to this color is broad: the concepts of loyalty and fidelity are associated with it, while warriors, writes Crollalanza, "wanted to express with it vigilance, fortitude, constancy, patriotism, victory and fame."[12] VariantsIt is possible to identify a number of alternative versions of the coat of arms of the House of Hauteville, which, while not evidently the result of misrepresentation or blazoning, are of uncertain attribution, nor do they allow a clear interpretation of the intervening variations. It is worth mentioning, for example, a variant of the coat of arms which differs from the original insignia, presenting, in the bend chequy, not two, but three rows of tiles.[13]  An example of misrepresentation, on the other hand, is found in the aforementioned Historia della città, e regno di Napoli by Summonte,[14] where at the base of the plates depicting Roger II[15] and the other Norman rulers[16] is reproduced a coat of arms that has a bend chequy, instead of the bend described by Summonte.[13] Inveges himself, although he explicitly points out the error present in those plates of the Historia,[14] when speculating that the coat of arms was adopted by Roger II, mentions a bend or strip.[1] Incidentally, the azure insignia to the bend chequy of gules and argent is linked to a hypothesis as suggestive as it lacks solid evidence: said thesis would have it that this was the coat of arms of the House of Drengot Quarrel, attributing the extreme similarity of it to the Hauteville insignia, arising from a series of marriage alliances, between the two families of Norman origin.[17] An erroneous blazoning of the coat of arms, on the other hand, can be traced in Sancetta: in the description provided by the latter, mention is made not of a band (honorable ordinary which, in the shield, descends diagonally from right to left), but of a bend sinister (honorable ordinary which, in the shield, descends diagonally from left to right).[1]

Within the range of alternative representations of the coat of arms, there would also fall a version of the coat of arms that features a reversal of colors, with the field becoming red, while the bend chequy is silver and azure. Such an insignia is described by the French heraldist André Favyn, in Le théâtre d'honneur et de chevalerie, a work that was printed in 1620. Favyn thus blazons "les Armes" of the Hauteville:

specifying that these would be the "premieres Armes de Scicile," thus, indirectly attributing to the Hauteville the primacy of having introduced heraldry to Sicily.[17] The same blazoning is also reported in the 1628 edition of the Histoire généalogique de la Maison de France, by the French historians Scévole II de Sainte-Marthe and Louis de Sainte-Marthe:[19] such an achievement is indicated, in the index of coats of arms attached to the first tome of the work, both as arme di Sicile ancien, and as arme di Sicile-Hauteville.[20] Finally, the insignia is illustrated by the mathematician and cartographer, also French, Oronce Finé, in the volume Giuoco d'armi dei sovrani e stati d'Europa, a didactic game published in 1681.[13]  Also in red is the field of the coat of arms attributed to Robert Guiscard in Promptuaire armorial et general divisé en quatre parties, a seventeenth-century work by the French cartographer Jean Boisseau. Compared to the insignia emblazoned by Favyn, this coat of arms associated with the ruler of the Duchy of Apulia and Calabria differs in one of the tinctures of the band, for while the metal remains silver, the color is black.[21]  Another unusual reconstruction of the coat of arms can be found in the Regum Neapolitanorum vitae et effigies, a Latin-language volume that was printed in 1605: some of the plates accompanying the publication show a coat of arms attributed to the Hauteville as characterized, not by one, but by as many as two bends chequy.[22] Such a double-banded representation can also be found in the Großes Wappenbuch, an armorial compiled from 1583 in southern Germany: on a red field, the two bends chequy, each of two rows, are of azure and silver.[23]

Finally, an interesting variant of the Hauteville insignia is reproduced inside the Holy Trinity Complex in Venosa. The coat of arms is included in a pictorial decoration, datable to the 16th century, made on the top of the arcosolium of the Hauteville tomb, a funerary ark, where William Iron Arm, Drogo of Hauteville, Humphrey of Hauteville and Robert Guiscard are buried. The coat of arms, trimmed in gold and gules, on a bend chequy with two azure and silver tiles, is held by two putti, which in turn are flanked by two shields with the Maltese cross of the Knights Hospitaller.[24]

Attributed coat of armsSeveral sources define this coat of arms as an "attributed" coat of arms, i.e., an insignia created and traced back to the Hauteville dynasty or, at any rate, to Roger II, only at a later date, since no certain traces or evidence contemporary to the time when the coat of arms would have been adopted can be found.[4] Specifically, although there are several clues that would trace the insignia back to the first Sicilian ruler or his immediate successors, they cannot be verified with absolute certainty. For example, tradition has it that at Castel dell'Ovo, which was the subject of significant fortification work during both the reign of Roger II and the reign of William I, the Normandy tower bore more of Roger II's coats of arms carved into it, as well as being adorned with his banners. Of said coats of arms, however, there is no longer a trace, as the tower was largely destroyed in the 15th century.[3] Another example is given by the Cathedral of Conversano, in which there are several examples of the coat of arms, which, however, it is not possible to date accurately, although they are dated to the second half of the 12th century.[3] Similar considerations, again, can be made for "the mosaic representations of the banded coat of arms" placed both inside and outside the cathedral of Monreale, since "they are believed to be of later date than the other famous mosaics."[17] Even more categorical is the position held by Luigi and Scipione Ammirato, who rule out that the Hauteville adopted their own blazon for the Sicilian realm and assert that the first coats of arms used for the Kingdom of Sicily and the later Kingdom of Naples were those introduced by Charles I of Anjou. Similarly, the French Jesuit and heraldist Claude-François Ménestrier, writing that "one would not know how to produce any other document of the bend chequy given to the Norman Kings of the blood of Tancred [...]," argues that, in the Kingdom of Naples, there would be no coat of arms older than those from the House of Anjou-Sicily.[17] Finally, some authors, in order to strengthen the thesis of the attributed coat of arms, note how this coat of arms, that is, the coat of arms of the founding ruling House of the Sicilian monarchy, was not taken up and framed in their own coats of arms by later dynasties and, in particular, by the House of Hohenstaufen and the House of Barcelona.[25] The Lion of HautevilleDifferent sources, as well as some material evidence from the period, document that the heraldic figure of the lion, derived from the House of Normandy, was also used by the House of Hauteville, both for the Duchy of Apulia and Calabria, where several dukes included it in their coats of arms, and for the County of Sicily.[26] Pietro Giannone, a Neapolitan jurist and historian, and Augustine Inveges, argue for the existence of a common lineage between the two houses:[27] from the dukes of Normandy, writes Inveges, "descend, according to the most probable opinion of the Historians, the Counts, the Dukes, & the Norman Kings of Sicily [...]".[1]

Specifically, it is interesting to note how the lion - which by definition is rampant - can be associated, reproduced, though, with different tinctures, with two extremely relevant figures in the history of the dynasty: Robert Guiscard and his younger brother Roger, the first count of Sicily. A shield with a red lion on a gold field, in fact, appears in a miniature of the Nova Cronica, which depicts the coronation of Guiscard, proclaimed duke by Pope Nicholas II, in 1059, during the first council of Melfi. The medievalist historian Glauco Maria Cantarella, however, reports that Count Roger's coat of arms was

In heraldry, the symbolism associated with the figure of the lion is vast, as is the spread of the figure itself, and various authors attribute multiple meanings and interpretations to this animal and its use. In his Tesserae gentilitiae, Silvestro Pietrasanta, a Jesuit and heraldist, explains that the lion, as a beast that goes hunting, represents nothing more than a captain moving to war. For French heraldist Claude-François Ménestrier, on the other hand, the different tinctures that characterize the lions inserted in the coats of arms of knights would symbolize overseas travel. In particular, Crollalanza, dwelling on the pairs of tinctures that distinguish field and figure, reports that the lion, "when it is red on a gold background, is a sign of a warrior who is entirely focused in execution, and full of fidelity in his deeds [...]," while "the black lion on a gold background denotes fortitude in a great soul [...]." The author of the Heraldic Chivalric Encyclopedia, however, does not fail to point out that such symbolism based on color combinations is entirely arbitrary "and owes itself only to the pen of certain heraldists."[30]  The heraldic figure of the lion can be traced not only to brothers Robert and Roger I, but also to Roger II. The latter, before becoming king, would have used, as did his father, his predecessor, a coat of arms bearing a rampant lion. The escutcheon, of which it is not possible to deduce the tinctures, can be seen in a miniature contained in Peter of Eboli's Liber ad honorem Augusti, which depicts the Norman, riding a horse launched at a gallop, while, with his right hand, he holds a flagstaff.[26]  Of the material evidence mentioned above, the most famous of them, the Mantle of Roger II, testifies that even after he assumed the title of king, the ancient symbol of the lion by no means fell into disuse. On the mantle of Roger II, which later became part of the so-called Insignia of the Holy Roman Empire, two lions (symbol of the Normans) appear, towering above two camels (symbol of the Saracens).[29] The lions depicted in the exquisite coat of arms made by the Nobiles Officinae of Palermo, however, appear different from the coat of arms previously used by the father of the first Sicilian king, Count Roger I: while the latter's coat of arms, as mentioned above, was gold with the lion in black, in his son's coat, gold remains, but there is also purple, a typical imperial color.[31] Bohemond I of Antioch, son of Guiscard, may also have used this heraldic animal for his own insignia: some sources from the 13th century, as well as some artistic artifacts from the same period, would attest that, among the coats of arms that would have been adopted by the Principality of Antioch, it would be possible to count a silver coat of arms with a lion or leopard in red. Specifically, one of the various hypotheses formulated regarding the origin of said insignia would trace it back precisely to Bohemond, founder of the Crusader State.[32] Agostino Inveges, on the other hand, makes no mention of the lion, but, as noted above, argues that, before the introduction of the coat of arms with the bend chequy, the Hauteville family also bore, as their own coat of arms, the crest of Normandy, that is, two leopards - beasts that by definition are passant - in gold, armed and langued in azure, placed in a pole on a red field;[1] an insignia, which to this day denotes the French region. Both Ginanni and Crollalanza agree in asserting that the coat of arms of England is the result of the union of the Norman and Guienne insignia, which consists of a single leopard in gold on a red field.[33][34] Such a coat of arms on which stands a single leopard, however, could also be ascribed, as Angelo Scordo reports, to the Hauteville themselves.[27] Other attributed coats of armsThe list of coats of arms attributed to the sovereigns of Apulia and Sicily does not end with the ones examined so far. Associated with the House of Hauteville and, in particular, with the figure of William the Good is another insignia, representations of which, alongside the better-known checkered coat of arms, can be observed at the Cathedral of Monreale, at the Church of Santa Maria la Nova in Palermo and in the work of the Sicilian archbishop, theologian and jurist Francesco Maria Testa, the De vita, et rebus gestis Guilelmi II. Siciliae regis, Monregalensis ecclesiae fundatoris:[27] this coat of arms is

In the Monreale cathedral, built precisely at the behest of King William, the said coat of arms appears reproduced in two specimens, which are part of a mosaic above the royal throne. In Testa's De vita, et rebus gestis Guilelmi II, also printed in Monreale, in 1769, a first engraving, which forms the volume's frontispiece, features a sculptural group, in which a portrait of the sovereign appears, below which is the octagonal star; while a second engraving, printed in the frontispiece, reproduces a coat of arms, set in an elaborate crowned frame, supported by three putti, two of which are winged, which is separated, first, from the band of two checkered rows, and, secondly, from the octagonal star.[35] The double reference to the city of Monreale makes it superfluous to point out that the civic coat of arms of Monreale is precisely composed of a gold octagonal star on a blue field. The question of the multiple attributions of insignia to the Siculo-Norman dynasty and the discordant positions taken by the various authors who have dealt with the Hauteville coat of arms is addressed by the Norman genealogist and heraldist Gilles-André de la Rocque.[36] In particular, in addition to the coat of arms with the bend chequy (in the red variant with silver and azure tiles, i.e., the coat of arms emblazoned by Favyn, which, in this regard, de la Rocque cites as a reference), the Norman author notes no less than four other insignia that different sources attribute "à la Maison d'Hauteville ou de Sicile-Antioche."[37]  The first of these is a silver coat of arms, at the branch of a fern in green, bound in gold, which the heraldist, citing as his source the de Sainte-Marthe brothers, attributes to the dynasty which, not coincidentally, he defines as being of "Sicily-Antiochia."[37] In the aforementioned 1628 edition of the Histoire généalogique de la Maison de France, a coat of arms

is defined as being from Antioch and associated with the figure of Bohemond I.[38] The second insignia to be mentioned by de la Rocque in his examination is represented in a manuscript, formerly preserved in the library of Jean and Émery Bigot, in Rouen, the ancient Norman capital. This coat of arms, associated with the lineage that had Tancred as its progenitor, presents, on a field of silver, three mallets or knives of black, well ordered:[39][40]

De la Rocque reports on another manuscript related to the city of Rouen, the Chronique de Normandie, which shows not one but two insignia, one of them a variant of the other, attributed to the Hauteville family. Both coats of arms are azure, charged with a cross of gold, which, in the first insignia, is set aside by four crosses, also of the same metal; while, in the second coat of arms, it is traversed over a field sown with crosses, again of gold.[36][40]

In the aforementioned Regum Neapolitanorum vitae et effigies, the plates depicting the effigies of the monarchs of the House of Hauteville (as well as of the later dynasties) show, in the corners at the base of them, on the one hand, the coat of arms of the lineage and, on the other, an allegorical crest attributed to each individual ruler: Roger II is flanked by an insignia on which a sword stands out; William the Bad, on the other hand, is attributed a crest with a lion; while more whimsical and elaborate are the coats of arms imagined for the other rulers.[42] Other heraldic symbols Within the broad iconographic production of the period, connected to the sovereigns of the House of Hauteville, there are several recurring elements to which it is possible to attribute a certain heraldic significance. Even before the establishment of the Kingdom, both for the continental territories and, later, for Sicily, the cross pattée alisée was employed as an emblem of administrative authority, emphasizing the Christianity of the state and the ruling dynasty.[26] There are several examples of the use of the cross pattée, one of them being the sarcophagus, dating from the 3rd century, which, later, was used for the burial of Roger I. On the side gables of the lid, where heads of Gorgons originally appeared, crosses pattées were carved. Other symbols regularly found in pictorial and sculptural representations that can be traced back to the royal dynasty, but which probably find their origins in past dominations of Sicily, include the palm tree, griffin, and eagle.[26] Precisely to this last figure, some fascinating speculations would be connected, which would have it that the eagle was much more than a simple iconographic element and that would have it risen to royal arms as early as the House of Hauteville.  Sancetta, in this regard, supports the thesis that the effigy of the eagle, intended as a symbol capable of representing Sicily, would find its origin in the Byzantine age. For the Sicilian historian, the strategoi of Syracuse would have assumed, for themselves and for Sicily, an insignia of silver with an eagle in black, crowned in gold. Later, this coat of arms would be readapted and taken up by Roger I and his successors.[43] Inveges, similarly, reiterates that "the Black Eagle is a very ancient Coat of Arms of the Kingdom of Sicily" (although he is unable to report which sovereign introduced it), but he believes that the field of the coat of arms was golden.[44] Evidence that the eagle was used by the Hauteville family would be found, Inveges reports, in a coin reproduced in the work of Sicilian numismatist Filippo Paruta, Della Sicilia descritta con medaglie:[43] the coin, struck during the reign of Roger II, shows an eagle in lowered flight, facing the heraldic right.[45] According to another hypothesis, to Tancred of Sicily, nephew of Roger II and king of Sicily from 1189 to 1194, a golden eagle, visible on a standard and on Tancred's helmet in some miniatures of the Liber ad honorem Augusti by Peter of Eboli, could be traced as a coat of arms.[26] Theories of an origin of the lowered-flying eagle coat of arms traceable to a period earlier than the rise of the House of Hohenstaufen to the throne of Sicily generate perplexity in the heraldist Angelo Scordo, according to whom, although the use of eagles as Sicilian symbols in the centuries preceding the advent of the Staufen is not to be ruled out, hypothesizing a relationship of direct derivation between these already existing symbols and the Staufian coat of arms comes across as an exercise lacking any concrete foundation.[46] Motto To the blazons, the Hauteville family also had mottoes accompanying them. The most famous and in use among them was of biblical derivation, taken from Psalm 118:

The first to use it was the devout Roger I, after the victorious battle of Cerami in 1063. From that time, precisely because of his military success, he had it engraved on his shields and carried on his own banners.[47] The same motto was later adopted by Roger II, probably starting in 1136, in Latin documents.[48] In a table accompanying the Dissertazioni sopra le antichità italiane by the presbyter and historian Ludovico Antonio Muratori, it is possible to observe a reproduction of Roger II's signum, which bears, in the legend circumscribing it, precisely the motto in question.[49] Finally, the stability of this formula is confirmed by the use made of it by Roger II's successor, his son William I, who had it engraved on the royal seal with which the Treaty of Benevento of 1156 was sealed.[50] To this biblically derived motto, Roger II added a more purely political one, engraved on his own sword[51] and, according to some sources, also on his own shield:[3]

In particular, Summonte reports that the motto was adopted by Roger II when the ruler managed to extend his rule over several territories in the North African coastal area: "[...] & at the time he had that verse carved into his sword for glory [...]. And he used it as an achievement [...]." The Neapolitan historian, therefore, in addition to attesting to the use of a coat of arms charged with the said motto, which he calls Roger's military achievement, reports as sources supporting his assertions the fifteenth-century historians Marcus Antonius Sabellicus and Pandolfo Collenuccio.[52] Similarly, de la Roque also reports that the motto in question was introduced by Roger II to exalt the expansion of his authority in the Mediterranean and, at the same time, does not fail to point out that the ruler had those words engraved on his own shield. Going into even more detail, the Norman heraldist points out that it is possible to infer that, outside of the motto itself, no other figure was represented on that coat of arms; this, however, de la Roque again specifies, does not exclude the use of emblems on other shields, by the Sicilian sovereign.[53] See alsoReferences

Bibliography

External links

|

||||||