|

Cave wolf

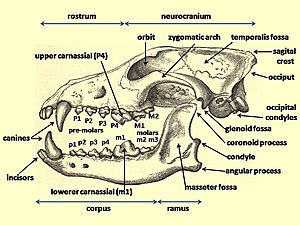

The cave wolf (Canis lupus spelaeus) is an extinct glacial mammoth steppe-adapted wolf that lived during the Middle Pleistocene to the Late Pleistocene. It inhabited Europe, where its remains have been found in many caves. Its habitat included the mammoth steppe grasslands and boreal needle forests.[6] This large wolf was short-legged compared to its body size,[3] yet its leg size is comparable with that of the Arctic wolf C. l. arctos.[6] Genetic evidence suggests that Late Pleistocene European wolves shared high genetic connectivity with contemporary wolves from Siberia, with continual gene flow from Siberian wolves into European wolves over the course of the Late Pleistocene. Modern European wolves derive most of their ancestry from Siberian wolf populations that expanded into Europe during and after the Last Glacial Maximum, but retain a minor fraction of their ancestry from earlier Late Pleistocene European wolves.[7] TaxonomyThe large wolf C. l. spelaeus Georg August Goldfuss, 1823 was first described based on a wolf pup skull found in the Zoolithen Cave located at Gailenreuth, Bavaria, Germany.[2] It is regarded as an ecomorph/chronosubspecies of C. lupus.[8] In Germany, cave wolf populations are known from three caves separated by a few kilometers from each other that are located on the Franconia Karst along the Wiesent and Ahorn River vallies in the Upper Franconia region of the state of Bavaria, Germany. Sophie's Cave sits on the northwest slope of the Ailsbach Valley near Rabenstein Castle in the Ahorntal municipality. Große Teufels Cave (Big Devil's Cave) and the Zoolithen Cave are located nearby.[9] They are also known from Hermann's Cave in the village of Rübeland near the town of Wernigerode, in the district of Harz, Saxony-Anhalt, Germany.[10] These large wolves have not been studied in any degree of depth, and their relationship to modern wolves has not been clarified using DNA.[11] Canis lupus bohemicaIn 2022, a new species Canis lupus bohemica was taxonomically described after having been discovered in the Bat Cave system located near Srbsko, Central Bohemia, Czech Republic. The Bohemian wolf is an extinct short-legged wolf that first appeared 800,000 years ago (MIS 20, the Rhumian Interglacial of the early Cromerian stage, Middle Pleistocene) and once inhabited what was part of the mammoth steppe. It is proposed as the ancestor of Canis lupus mosbachensis. In comparison, C. etruscus appears to be the ancestor of the Afro-Eurasian jackal.[6] In Hungary in 1969, a tooth (the premolar of the Maxilla) was found which dated to the Middle Pleistocene, and was assessed as being midway between that of Canis mosbachensis and the cave wolf Canis lupus spelaeus, but leaning towards C.l. spelaeus.[12] During the late Middle Pleistocene around 600,000 years ago, the Bohemian wolf diversified into two wolf lineages that specialized for different environmental and climatic conditions. One was a southern interglacial (warm climate) grey wolf of Europe which was to become the Mosbach wolf, and the other a northern glacial white wolf of Eurasia which was to become C. l. spelaeus.[6] Canis lupus brevisThe Don wolf Canis lupus brevis Kuzmina and Sablin, 1994 is an extinct wolf whose fossil remains were found at the Kostenki I Late Pleistocene site by the Don River at Kostyonki, Voronezh Oblast, Russia and reported in 1994. Based on the size of its dental rows, the Don wolf was bigger than modern wolves from the tundra or the Middle Russian taiga. The length of its P4 was longer than the row of its molars M1-M2, which is different to the Late Pleistocene wolves from the Caucasus or the Ural Mountains. Its main characteristic was its shorter legs, due to shorter humerus, radius, metacarpals, tibia, and metatarsals.[3] This warm climate grey wolf existed at the same time as C. l. spelaeus.[6] In 2009, a study compared the skull of one of these wolves to those found in Western Europe, and proposed that C. l. brevis of eastern Europe and C. l. spelaeus of western Europe are taxonomic synonyms for the same subspecies.[5][6] These were both comparable to the remains of a 16,000 YBP wolf skull found on the Taimyr peninsula in far northern Siberia.[5] Canis lupus maximusThe large wolf Canis lupus maximus Boudadi-Maligne, 2012 was a subspecies larger than all other known fossil and extant wolves from Western Europe. The fossilized remains of this Late Pleistocene subspecies were found across a wide area of south-western France at: Jaurens cave, Nespouls, Corrèze dated 31,000 YBP; Maldidier cave, La Roque-Gageac, Dordogne dated 22,500 YBP; and Gral pit-fall, Sauliac-sur-Célé, Lot dated 16,000 YBP. The wolf's long bones are 10 percent longer than those of extant European wolves and 20 percent longer than its probable ancestor, C. l. lunellensis. The teeth are robust, the posterior denticules on the lower premolars p2, p3, p4 and upper P2 and P3 are highly developed, and the diameter of the lower carnassial (m1) were larger than any known European wolf.[4] Wolf body size in Europe has followed a steady increase from their first appearance up to the peak of the Last Glacial Maximum. The size of these wolves are thought to be an adaptation to a cold environment (Bergmann's rule) and plentiful game as their remains have been found in association with reindeer fossils.[4] In 2022, a paleontologist proposed that C. l. maximus was a taxonomic synonym for C. l. spelaeus.[6] Italian wolvesA 2014 study found wolves in Late Pleistocene Italy were comparable in tooth morphology – and therefore in size – with C. l. maximus from France. These wolves were found near Avetrana, Taranto and near Buco del Frate, Brescia and Pocala cave in Friuli-Venezia Giulia.[13] DescriptionThe short-legged C. l. spelaeus was a glacial mammoth steppe-adapted white wolf. It first appeared 320,000 years ago (MIS 8, Middle Pleistocene), and disappeared along with the mammoth steppe and cave bear fauna at the end of the Late Pleistocene, somewhere between 24,000-12,000 years ago (MIS 2). Compared with the modern day Arctic wolf C. l. arctos and the Siberian Tundra wolf C. l. albus, its legs are shorter than the Tundra wolf but similar to the Arctic wolf and may be its ancestor.[6] During MIS 8-3, its habitat included the mammoth steppe grasslands and boreal needle forests. It spread across all of Europe through the middle-high elevated mountains, and followed mountain glaciers down to the Mediterranean. This wolf specialized in feeding on cave bear carcasses found inside of caves, and did more damage to its teeth in doing so than any other wolf subspecies.[6] Its bone proportions are close to those of the Canadian Arctic-boreal mountain-adapted timber wolf and a little larger than those of the modern European wolf. Some postcranial bones have similarly large proportions to those from the Sophie's and Große Teufels Caves,[9] where the bone sizes are closer to those of Scandinavian Arctic and Canadian Columbian wolf subspecies than to those of the smaller European wolves. Bone sizes are one-eighth larger than European wolves, and this wolf was a specialized Late Pleistocene wolf ecomorph.[14]  During the Late Pleistocene, C. l. spelaeus exhibited a changed skeletal development due to the harsh climatic and environmental conditions, and a preference for taking larger prey. This resulted in a larger and more robust wolf with a shortened rostrum, a pronounced development of the temporalis muscles, and proportionally enlarged and wider premolars and carnassials. These features were specialised adaptations for the processing of fast-freezing carcasses associated with the hunting and scavenging of larger prey. Some populations of C. l. spelaeus showed an increase in tooth breakage when compared with the extant C. lupus because they were habitual bone crackers. The large dimensions, robust build and cranio-dental adaptations formed at this time enabled these wolves to hunt larger prey, making the adult Steppe Bison Bison priscus a more attainable target than for their C. lupus relatives.[15] Adaptation Their dens have been identified, with the Zoolithen Cave supporting a large population and has yielded more than 380 bones as well as several skulls (including a holotype). Sophie's Cave has demonstrated the first "Early Late Pleistocene wolf den", with intensive faecal places and the first European record of half-digested cave bear bones found within the faecal areas in the cave. It demonstrates that wolves seem not to have used this cave as a cub-raising den, but that they were cave dwellers that fed on cave bear carcasses, similar to but less so than cave hyenas, but more so than cave lions. The abundant faeces seem to play a role in the "orientation" for trail tracking, similar to modern wolves, and less as den marking. The high abundance in a limited area of the Bear's Passage of the cave might be the result of periodical short-term den use of smaller cave areas. Wolves were scavenging on the bears that hibernated and died there, and therefore a simultaneous use as both a wolf and a cave bear den cannot be expected. Remains of a skeleton of at least one high adult wolf also might have been the result of a battle within the cave with the bears, the same as in the lion taphonomic record.[11] The ecology of the early to middle Late Pleistocene wolves on the mammoth steppe and the boreal forests is not known, nor is whether they used caves as dens.[11] All of the top predators in Europe commenced going extinct with the loss of the pleistocene megafauna when conditions became colder during the peak of the Last Glacial Maximum around 23,000 years ago. The last cave wolves used the side branches of the main caves to protect their pups from the cold climate.[14] During this time the cave wolf was replaced by a smaller wolf-type, which then disappeared along with the reindeer, to finally be replaced by the Holocene warm-period European wolf Canis lupus lupus.[11] Relationship with the dogMitochondrial DNA (mDNA) passes along the maternal line and can date back thousands of years.[16] Therefore, phylogenetic analysis of mDNA sequences within a species provides a history of maternal lineages that can be represented as a phylogenetic tree.[17][18] In 2013, a study analysed the complete and partial mitochondrial genome sequences of 18 fossil canids dated from 1,000 to 36,000 YBP from the Old and New Worlds, and compared these with the complete mitochondrial genome sequences from modern wolves and dogs. Phylogenetic analysis showed that modern dog mDNA haplotypes resolve into four monophyletic clades with strong statistical support, and these have been designated by researchers as clades A-D.[19][20][21] Based on the specimens used in this study, clade A included 64% of the dogs sampled and these were sister to a 14,500 YBP wolf sequence from the Kessleroch cave near Thayngen in the canton of Schaffhausen, Switzerland, with a most recent common ancestor estimated to 32,100 YBP. This group of dogs matched three fossil pre-Columbian New World dogs dated between 1,000 and 8,500 YBP, which supported the hypothesis that pre-Columbian dogs in the New World share ancestry with modern dogs and that they likely arrived with the first humans to the New World.[19] Clade C included 12% of the dogs sampled and these were sister to two ancient dogs from the Bonn-Oberkassel cave (14,700 YBP) and the Kartstein cave (12,500 YBP) near Mechernich in Germany, with a common recent ancestor estimated to 16,000–24,000 YBP. Clade D contained sequences from 2 Scandinavian breeds (Jamthund, Norwegian Elkhound) and were sister to another 14,500 YBP wolf sequence also from the Kesserloch cave, with a common recent ancestor estimated to 18,300 YBP. Its branch is phylogenetically rooted in the same sequence as the "Altai dog" (not a direct ancestor). The data from this study indicated a European origin for dogs that was estimated at 18,800–32,100 years ago based on the genetic relationship of 78% of the sampled dogs with ancient canid specimens found in Europe.[22][19] The data supports the hypothesis that dog domestication preceded the emergence of agriculture[20] and was initiated close to the Last Glacial Maximum when hunter-gatherers preyed on megafauna.[19][23] This genetic analysis indicates that C. l. spelaeus possessed mitochondrial lineages which cannot be found among the modern C. lupus, and therefore they are now extinct. It also indicates that the domestic dog C. l. familiaris descended from these extinct lineages.[15] See alsoReferences

Bibliography

External links |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||