|

Blue-billed duck

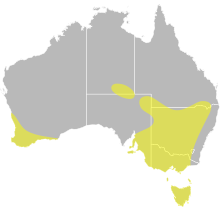

The blue-billed duck (Oxyura australis) is a small Australian stiff-tailed duck, with both the male and female growing to a length of 40 cm (16 in).[2][3] The male has a slate-blue bill which changes to bright-blue during the breeding season, hence the duck's common name. The male has deep chestnut plumage during breeding season, reverting to a dark grey. The female retains black plumage with brown tips all year round. The duck is endemic to Australia's temperate regions, inhabiting natural inland wetlands and also artificial wetlands, such as sewage ponds, in large numbers. It can be difficult to observe due to its cryptic nature during its breeding season through autumn and winter. The male duck exhibits a complex mating ritual. The blue-billed duck is omnivorous, with a preference for small aquatic invertebrates. BirdLife International[1] has classified this species as Least concern. Major threats include drainage of deep permanent wetlands, or their degradation as a result of introduced fish, peripheral cattle grazing, salinization, and lowering of ground water.[4] TaxonomyThe blue-billed duck was described in 1836 by ornithologist John Gould. The specific name australis is derived from the Latin for "southern", hence Australian. Description  The tail feathers for both the male and female are made up of thick, spine-like shafts. The tail is usually held flat on the surface of the water, or held erect when defensive. The male also holds the tail erect during courtship displays. The feet are quite powerful, which aids in swimming and diving. The duck sits low in the water in comparison to other ducks.[2] During breeding season, apart from the aforementioned bright-blue bill, the male's head and neck are glossy black, and the back and wings are a rich chestnut. During the non-breeding season, the head changes from its glossy black to black with grey speckles, and its body changes from chestnut to dark grey.[2] Some males retain breeding plumage throughout the year.[3] The female's plumage does not change throughout the year. Its head is dark brown, and the back and wings consist of black feathers with a light-brown tip, giving a mottled appearance, although the National Parks and Wildlife publication[5] on O. australis refers to bands on each feather rather than a single feather-tip colouration. The female blue-billed duck has a dark grey-brown bill and grey-brown feet, while the male's feet are grey. Both males and females have brown irises. Juvenile blue-billed ducks have a resemblance to adult females but appear paler and have a grey-green bill. Distribution and habitatThe blue-billed duck is endemic to Australia's temperate regions.[3][6] Its range extends from southern Queensland, through New South Wales and Victoria, to Tasmania. The species is also widespread in the south west of Western Australia. O. australis rarely appears on the New South Wales coastline except during times of drought. It is in greatest abundance in the Murray-Darling basin.[7] The blue-billed duck is almost entirely aquatic. While they have been observed on land, they have difficulty walking,[2] exhibiting a penguin-like gait.[3] During non-breeding season, many ducks gather in flocks totalling several hundred,[8] especially juveniles and younger adults, in open lakes or dams in autumn and winter, far from the shore. For the rest of the year, during breeding season, the blue-billed duck prefers deep, freshwater swamps, with dense vegetation including cumbungi Typha orientalis (broadleaf cumbungi) and Typha domingensis (narrow-leaved cumbungi); although it has appeared in lignum swamps in more coastal areas,[2][3][9] especially in drier seasons.[7] They have also occasionally been found in large rivers and saline water bodies such as billabongs.[2][3] Ecology and behaviourThe behaviour of O. australis depends on its breeding cycle. The ducks gather in large flocks on lakes during the winter while not breeding, although some mature adults remain in vegetative swamps and continue to breed. They will also fly more frequently, probably due to the open habitat, and escape threats by flying. While breeding, O. australis is secretive and wary,[10] and it will swiftly and quietly dive under water if threatened, resurfacing a large distance away, rather than escape by flying. The blue-billed duck has a low quack, which is seldom heard. The courting repertoire of the male is very complex and elaborative.[2][3][8] It includes such behaviour as rolling the cheek on the back, dab-preening (also sometimes performed by females), and sousing, where the head is thrown into the water in a prone position, and the back arched as if in spasm, with possibly the legs throwing spray above the body.[2][3] After the courtship ritual, and a vigorous chase, copulation follows with the female completely submerged. The birds then separate and preen themselves. In preparation for laying eggs, the female builds the nest, at which time the male will mostly desert the female.[2][3] DietOxyura australis is omnivorous, where invertebrates as well as seeds, buds, and fruit of emergent and submerged plants are eaten. The duck feeds underwater by sifting mud with its beak.[3] O. australis does have a preference for small invertebrates, including molluscs and aquatic insects such as chironomid larvae, caddis flies, dragonflies and water beetle larvae.[6][11] Its diverse range of food is reflective of a relatively abundant habitat. The chironomid larvae are quite common in inland cumbungi swamps, and therefore make up a large portion of the diet of O. australis during its breeding season.[2] Blue-billed ducks can stay underwater for 10 seconds on average while feeding.[3] ReproductionThere is evidence that O. australis is partly migratory, with movement from breeding swamps of inland NSW to the Murray River during autumn and winter. Frith[2] claims O. australis is the most migratory of all Australian ducks. Marchant and Higgins[3] discredits this regular yearly migration, due to juveniles and young adults searching for new breeding grounds, especially on the fringes of the duck's range, with mature breeding adults often remaining. Indeed, experienced dominate adults are sedentary in breeding swamps[2][3] since migration would expend energy that instead would be used for breeding. Year-long sedentary adult breeding is confirmed by the observation that the laying period of ducks in captivity is continuous, reflecting “opportunistic breeding”.[3] Any variation in non-captive laying is in accordance to water-levels and hence abundance of food, a fact in contrast to Frith's description of reproduction being tied to the months between September and November.[3] Clutch size ranges from 3 to 12, the most common being 5 to 6, according to Marchant and Higgins.[3] Large clutch sizes indicate two females laying eggs in the one nest. It appears that a female will sometimes parasitise another's efforts at incubation, described as "facultative parasitism", by laying "dump clutches" in nests other than her own.[3] There is also some evidence of the duck laying its eggs in nests occupied by other water-birds.[9] The incubation is 26 to 28 days. After hatching, the young remain in the nest for one day, and are then led by the female from the nest. The young are relatively independent of the parents, being able to feed themselves immediately. The female will protect her brood, including hatchlings from dump clutches of other females.[3] At eight weeks, ducklings are of a similar size to the parents. Within one year, most have full adult plumage. Yearlings in captivity were observed to be able to breed.[3] ConservationTwo substantial land uses combine to have a significant impact on the blue-billed duck. These are: the regulation of wetland ecosystems through drainage, flood mitigation and water harvesting; and vegetation loss due to clearing, overgrazing and salinity.[6][7] Both result in smaller habitat sizes suitable to water birds. To counteract these impacts, the Department of Environment and Conservation has devised several strategies to increase the blue-billed duck's population.[11] They include retaining sustainable water flows and developing salinity management plans and farm management plans. The Australian population of blue-billed ducks is estimated to be 12 000, although the creation of artificial wetlands such as water treatment works disguise the number occurring in natural wetlands.[6] The blue-billed duck's vulnerable status has been de-listed for the Environmental Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999,[12] although they are currently recognized as vulnerable in NSW, according to the Department of Environment and Climate Change NSW.[7] The blue-billed duck is listed as "threatened" on the Victorian Flora and Fauna Guarantee Act (1988).[13] Under this Act, an Action Statement for the recovery and future management of this species has been prepared.[14] In Victoria, the blue-billed duck is also listed as endangered on the 2007 advisory list of threatened vertebrate fauna within the state.[15] Relationship with humansThe health of wetland ecosystems can be determined by the abundance of waterbird species. A decline in bird numbers provides a warning that the natural ecological functioning of the freshwater system is at risk.[11][16] Despite short term gains for farmers through permanent flooding, sustainability of wetland systems would decrease. Any long-term decrease in the population of waterbirds such as O. australis, which continue to breed yearlong, irrespective of drought conditions by seeking out suitable habitat, would make excellent indicators for wetland health. Any long-term decrease in the duck's population would therefore be caused by habitat loss through factors such as salinity and overgrazing more so than drought. Other commentsMore field research is needed into the average lifespan of O. australis in the wild; although, based on the high number of eggs in a clutch, and maturing 12 months after hatching would indicate a short life span of less than 10 years. Captive ducks were still breeding at 16 years.[3] Further research into the accuracy of using O. australis as an indicator for habitat health, among other waterbirds, is needed, considering its ability to breed every season despite the effects of drought. Any long-term decrease in populations of O. australis would therefore more strongly reflect poor wetland ecosystem health, without the confounding effects of natural drought cycles. References

External links

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||