|

Betsy Ross flag

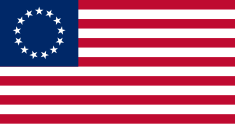

The Betsy Ross flag is an early design for the flag of the United States, which is conformant to the Flag Act of 1777 and has red stripes outermost and stars arranged in a circle. These details elaborate on the 1777 act, passed early in the American Revolutionary War, which specified 13 alternating red and white horizontal stripes and 13 white stars in a blue canton. Its name stems from the story, once widely believed, that shortly after the 1777 act, upholsterer and flag maker Betsy Ross produced a flag of this design.[1] Betsy Ross story Betsy Ross (1752–1836) was an upholsterer in Philadelphia who produced uniforms, tents, and flags for Continental forces. Although her manufacturing contributions are documented, a popular story evolved in which Ross was hired by a group of Founding Fathers to make a new U.S. flag. According to the legend, she deviated from the six-pointed stars in the design and produced a flag with five-pointed stars, instead. George Washington was a member of the Masonic Lodge, and their use of the six-pointed star may have influenced Washington's choice of six-pointed stars for his headquarters flag. [2] The claim by her descendants that Betsy Ross contributed to the flag's design is not generally accepted by modern American scholars and vexillologists.[3] Ross became a notable figure representing the contribution of women in the American Revolution,[4] but how this specific design of the U.S. flag became associated with her is unknown. An 1851 painting by Ellie Sully Wheeler of Philadelphia displayed Betsy Ross sewing a U.S. flag.[5][6] The National Museum of American History suggests that the Betsy Ross story first entered into American consciousness about the time of the 1876 Centennial Exposition celebrations.[7] In 1870, Ross's grandson, William J. Canby, presented a paper to the Historical Society of Pennsylvania in which he claimed that his grandmother had "made with her hands the first flag" of the United States.[8] Canby said he first obtained this information from his aunt Clarissa Sydney Wilson (née Claypoole) in 1857, twenty years after Betsy Ross's death. In his account, the original flag was made in June 1776, when a small committee – including George Washington, Robert Morris and relative George Ross – visited Betsy and discussed the need for a new U.S. flag. Betsy accepted the job to manufacture the flag, altering the committee's design by replacing the six-pointed stars with five-pointed stars. Canby dates the historic episode based on Washington's journey to Philadelphia, in late spring 1776, a year before Congress passed the Flag Act.[9] Ross biographer Marla Miller notes that even if one accepts Canby's presentation, Betsy Ross was merely one of several flag makers in Philadelphia, and her only contribution to the committee's design was the change in star shape from six-pointed to five-pointed.[10] In 1878, Col. J. Franklin Reigart published a somewhat different story in his book, "The history of the first United States flag, and the patriotism of Betsy Ross, the immortal heroine that originated the first flag of the Union." Reigart remembers visiting his great aunt, Mrs. Betsy Ross, in 1824 during the time of General Lafayette's visit to Philadelphia. In this version, Dr. Benjamin Franklin replaces George Washington. Together with George Ross and Robert Morris, they request that Mrs. Ross design the first flag. The Canby version and the subsequent 1909 book with the Ross family affidavits never specify the arrangement of stars. Reigart, however, describes Mrs. Ross's flag with an eagle in the canton with 13 stars surrounding its head. The cover of Reigart's book shows the 13 stars in a 3-2-3-2-3 lined pattern in the canton.[11] The earliest connection between Betsy Ross and this flag design with 13 stars in a circle was Charles Weisgerber's 1893 painting "Birth of Our Nation's Flag."[12][13] The 9 x 12-foot painting was first displayed at the 1893 Columbian Exposition in Chicago and depicts Betsy Ross with the flag on her lap.[14] In developing his work, Weisgerber was in touch with the descendants of Betsy Ross.[15] He would have needed a design for the flag in his painting. The most likely source of his design is the 1882 edition of History of the Flag of the United States of America by George Henry Preble, a flag scholar in the late 1800s.[16] Preble himself did not discuss the arrangement of the stars on the 1777 design. The book's illustrators, however, did provide a flag design for the 1777 flag. The illustrators may have used the flag design from Emanuel Leutze's 1851 painting Washington Crossing the Delaware. Consequently, the editions of Preble's book in 1872, 1880, and 1882, all show the 1777 flag as having a circle of 13 stars. It is also possible that Weisgerber used a July 1873 issue of Harper's Weekly Magazine as his source to find out what a 1777 flag looked like. This article published one year after Preble's first edition, showed this flag with the label, "Flag Adopted by Congress, 1777."[17] Weisgerber later helped start the foundation that restored 239 Arch Street in Philadelphia as the Betsy Ross House,[18] though Ross may have actually lived in the demolished house next door.[19] Weisgerber promoted the story of Betsy Ross by sending prints of the painting to foundation donors. It was reported in 1928 that he received donations from 4 million children and adults.[20] In 1897, the New York City School Board approved the order of framed prints for all schools in their system.[21] Canby Account Ross's grandson, William Canby, publicly presented a version of her story to the Historical Society of Pennsylvania in 1870.[22] Two years later, George Henry Preble cast doubt on Canby's report in his 1872 "Our Flag: Origin and Progress of the Flag of the United States of America.[23] Canby's 1870 account remains popular American folklore, but has been the source of some debate. Although the account has supporters, there is a lack of historical evidence and documentation to support Canby's story.[24][a] While modern lore may exaggerate the details of her story, Canby's account of Betsy Ross never claimed any contribution to the flag design except for the five-pointed star.[10][25] Additionally, arguments against Canby's story include:

Supporters of Canby's story defend his account with arguments including:

First Flag Canby's account and similar versions of the Betsy Ross tale often refer to this design as the first U.S. flag, but there is no consensus on what the first U.S. flag looked like, nor who produced it. There were at least 17 flag makers and upholsterers who worked in Philadelphia during the time these early American flags were made. Margaret Manny is thought to have made the first Continental Colors (or Grand Union Flag), but there is no evidence to prove she also made the Stars and Stripes. Other flag makers of that period include Rebecca Young, Anne King, Cornelia Bridges, and flag painter William Barrett. Hugh Stewart sold a "flag of the United Colonies" to the Committee of Safety, and William Alliborne was one of the first to manufacture United States ensigns.[36] Any flag maker in Philadelphia could have sewn the first American flag. Even according to Canby, there were other variations of the flag being made at the same time Ross was sewing the design that would carry her name. If true, there may not be one "first" flag, but many. The Marine Committee of the Second Continental Congress passed a Flag Resolution on June 14, 1777, establishing the first congressional description of official United States ensigns. The shape and arrangement of the stars is not mentioned – there were variations – but the legal description legitimized the Ross flag and similar designs.

As late as 1779, the War Board of the Continental Congress had still not settled on what the Army Standard of the United States should look like. The Board sent a letter to General Washington asking his opinion, and submitting a design that included a serpent, as well as a number corresponding to the state that flew the flag.[38] Francis Hopkinson is often given credit for a number of 13-star arrangements, including the Betsy Ross design. In a 1780 letter to the Continental Board of Admiralty dealing with the Admiralty seal,[39] Hopkinson mentioned patriotic designs he created in the past few years, including "the Flag of the United States of America." He asked for compensation for his designs, but his claim for full compensation was rejected. Hopkinson was not the only person consulted on designing the Great Seal of the United States. Furthermore, he was a public servant and thus was already on the government's payroll.[40] George Henry Preble states in his 1882 text that no one knows who designed the 1777 flag,[41] and that no combined stars and stripes flag was in common use prior to June 1777.[42] Historian Laurel Thatcher Ulrich argues that there was no "first flag" worth arguing over.[43] Ross biographer Marla Miller asserts that the question of Betsy Ross's involvement in the flag should not be one of design, but of production and entrepreneurship.[31] Researchers accept that the United States flag evolved, and did not have one design. Grace Rogers Cooper dates the earliest appearance of the "Ross" design as 1792, but with six-pointed stars.[44] Her research for the Smithsonian Institution found 17 examples of 13-star flags that were in existence between 1779 and ca. 1796.[45] Marla Miller writes, "The flag, like the Revolution it represents, was the work of many hands."[46] Symbolism Because the flag evolved during the American Revolutionary War, the meaning of the design is uncertain. Historians and experts discredit the common theory that the stripes and five-pointed stars derived from the Washington family coat of arms.[47] While this theory adds to Washington's legendary involvement in the development of the first flag, no evidence exists to show a connection between his coat of arms and the flag, other than that his coat of arms has stars and stripes in it. Washington frequently used his family coat of arms with three five-pointed red stars and three red-and-white stripes, on which is based the flag of the District of Columbia. StripesDuring the Revolutionary War era and into the 19th century, the "Rebellious Stripes" were considered as the most important element of United States flags, and were almost always mentioned before the stars.[48] The usage of stripes in the flag may be linked to two pre-existing flags. A 1765 Sons of Liberty flag flown in Boston had nine red and white stripes, and these "rebellious stripes" would influence later designs leading up to the American Revolution.[49] A flag used by Captain Abraham Markoe's Philadelphia Light Horse Troop in 1775 had 13 blue and silver stripes.[50] One or both of these flags likely influenced the design of the American flag. StarsThe canton, featuring the stars, may have gradually replaced the Grand Union flag as hope for reconciliation faded.[51] Regimental flags featuring stars in a blue canton, such as those of the Green Mountain Boys or 1st Rhode Island Regiment, may have pre-dated the 1777 Flag Resolution.[51] Stars were important symbols in European heraldry, their meaning differing with the shape and number of points. Stars appear in colonial flags as early as 1676.[b] Some have speculated that stars may be linked to Freemasonry, but stars of this type were not an important icon in Freemasonry.[52] Although early American flags featured stars with various numbers of points, the five-pointed star is a defining feature of the Betsy Ross legend. The five-pointed star became the norm on Navy ensigns, perhaps because five-pointed stars were more clearly defined from a distance.[53] Circle The shape and arrangement of the stars varied widely throughout the 18th and 19th centuries, and remains undefined by the various flag acts. In the late 18th century, a circle of stars, also known as a "wreath"[54] or "medallion" arrangement,[55] was a favorite for painters and coin designers, as well as some flag makers.[55] The circle generally represented unity between the states, with no state more dominant than any other.[56] Circular arrangements similar to the "Betsy Ross" design were seen as early as 1777 at the surrender of General John Burgoyne at Saratoga. Eyewitness Alfred Street wrote:

A flag with a circle of stars was again found in 1782, in William Barton's 2nd design for the Great Seal of the United States. Barton described the circle as a "symbol of eternity."[10] Ironically, although the circle of stars is a feature of the "Betsy Ross" design, none of Betsy Ross's family documents mention this arrangement. Circumstantial evidence from the Betsy Ross House suggests that Betsy Ross may have arranged her stars in rows.[10] Several U.S. flags after the Betsy Ross flag use a circle of stars in their designs. This includes the Cowpens flag, the Bennington flag, the flag of the U.S. (1861–1863),[58] the flag of the U.S. (1863–1865),[59] the wagon wheel U.S. flag,[60] the Medallion Centennial U.S. flag,[61] and the flag of the U.S. (1877–1890).[62] ColorsEarly US flags used a wide variety of colors,[63] and there is no known documented meaning behind the colors of the flag until Charles Thomson, in his 1782 report to Congress on the Great Seal of the United States, wrote "The colours of the pales are those used in the flag of the United States of America. White signifies purity and innocence. Red hardiness and valour and Blue the colour of the Chief signifies vigilance perseverance and justice."[64] The use of red and blue in flags at this time in history may derive from the relative fastness of the dyes indigo and cochineal, providing blue and red colors respectively, as aniline dyes were unknown. However, the most simple explanation for the colors of the American flag is that it was modeled after British flags. For example, the Grand Union Flag, a predecessor to early stars and stripes designs, was likely based on the King's Colours or East India Company flag. Political and cultural significance The Betsy Ross design, with its easily identifiable circle of stars, has long been regarded as a symbol of the American Revolution and the young Republic.[67] William J. Canby's recounting of the event appealed to Americans eager for stories about the revolution and its heroines. Betsy Ross was promoted as a patriotic role model for young girls and a symbol of women's contributions to American history.[68] A circle of thirteen stars in the same order as the Betsy Ross flag was used on the first official Confederate flag; however, instead of representing the original thirteen states, the stars represent the thirteen Confederate states. The Betsy Ross flag design is featured prominently in a number of post-Revolutionary paintings about the war, such as General George Washington at Trenton (1792)[d] and Washington Crossing the Delaware (1851). During the United States centennial, not long after the presentation by William Canby, the Betsy Ross design became a highly produced and popular flag.[70] The traditional backdrop at quadrennial United States presidential inaugurations uses a large Betsy Ross flag and the modern US flag to represent the history of the nation. Since the 1980s, this display also includes a US flag design symbolizing the year the president's home state was admitted to the union. During the inaugurations of Donald Trump and Joe Biden, the Betsy Ross flag was placed next to another 13-star Hopkinson flag design to represent the states of New York and Delaware, respectively.[71][72] The circle of 13 stars, which defines the Betsy Ross design, is found on four state flags: the flag of Rhode Island, the flag of Georgia, the flag of Indiana, and the flag of Ohio. The flags of New Hampshire and Missouri feature a similar circle of 9 and 24 stars, respectively, signifying their order of admittance to the country. The flag of Mississippi also features a similar circular arc of 20 stars, excluding the gold star, as it was admitted as the 20th state. The United States Foreign Service flag also features the circle of 13-stars. Since 1963, the Philadelphia 76ers have used the distinctive ring of 13 five-pointed stars in their team logo,[73] as a reference to Philadelphia as the first United States capital, where the Declaration of Independence was signed and where Betsy Ross worked. U.S. postage stamps featuring the Betsy Ross flag design

See alsoNotes

References

Bibliography

External linksWikimedia Commons has media related to Flags of the American Revolution. |

||||||||||||

![3¢ stamp issued in 1952 to commemorate Betsy Ross' 200th birthday.[74]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/f/f6/BetsyRossBicentennial-1952.jpg/180px-BetsyRossBicentennial-1952.jpg)

![A 6¢ stamp with the Betsy Ross design was released in 1968 as part of the "Historic Flag" series.[75]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d5/First_Stars_and_Stripes_Flag_-_Historic_Flag_Series_-_6c_1968_issue_U.S._stamp.jpg/180px-First_Stars_and_Stripes_Flag_-_Historic_Flag_Series_-_6c_1968_issue_U.S._stamp.jpg)

![10¢ stamp released in 1973, showing a 50-star flag and a Betsy Ross flag together, to commemorate the United States Bicentennial.[76]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/c/c0/10c_stamp_1973_50_star_and_13_star.png/166px-10c_stamp_1973_50_star_and_13_star.png)

![1975 13¢ stamp features the Betsy Ross flag behind Independence Hall[77]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/e/ee/Flag_over_Independence_Hall_stamp.png/169px-Flag_over_Independence_Hall_stamp.png)