|

Battle of Marj al-Saffar (1303)

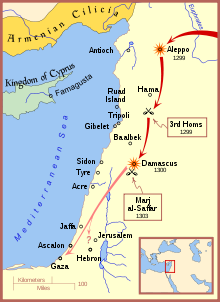

The Battle of Marj al-Saffar (or Marj al-Suffar), also known as the Battle of Shaqhab, took place on April 20 through April 22, 1303 between the Mamluks and the Mongols and their Armenian allies near Kiswe, Syria, just south of Damascus. The battle has been influential in both Islamic history and contemporary time because of the controversial jihad against other Muslims and Ramadan related fatwas issued by Ibn Taymiyyah, who himself joined the battle.[7] The battle, a disastrous defeat for the Mongols, put an end to Mongol invasions of the Levant. Previous Mongol-Muslim conflictA string of Mongol victories, starting in 1218 when they had invaded Khwarezm, quickly gave the Mongols control over most of Persia as well as the Abbasid Dynasty of Iraq and the Seljuk Sultanate of Rum of Asia Minor. Incorporating troops from vassal countries such as Cilician Armenia and the Kingdom of Georgia, the Mongols had sacked Baghdad in 1258, followed by the taking of Aleppo and Damascus in 1260. Later that same year, the Mongols had experienced their first major defeat at the Battle of Ain Jalut, which eventually forced the Mongols out of Damascus and Aleppo and back across the Euphrates. Nearly 40 years later, the Ilkhan Ghazan once again invaded Syria, retaking Aleppo in 1299. Ghazan defeated Mamluk forces at the Battle of Wadi al-Khazandar that same year, and Damascus quickly surrendered to him. After sending raiding parties as far south as Gaza, Ghazan withdrew from Syria. Events just before the battleIn 1303, Ghazan sent his general Qutlugh-Shah with an army to recapture Syria. The inhabitants and rulers of Aleppo and Hama fled to Damascus to escape the advancing Mongols. However, Baibars II was in Damascus and sent a message to the Sultan of Egypt, Al-Nasir Muhammad, to come to fight the Mongols. The Sultan left Egypt with an army to engage the Mongols in Syria, and arrived while the Mongols were attacking Hama. The Mongols had reached the outskirts of Damascus on April 19 to meet the Sultan's army. The Mamluks then made their way to the plain of Marj al-Saffar, where the battle would take place. BattleThe battle commenced on 2 Ramadhan 702 in the Hijri calendar, or April 20, 1303. Qutlugh-Shah's army was positioned near a river. Hostilities began when Qutlugh-Shah's left wing attacked the Mamluk's right wing with his brigade of 10,000 soldiers. The Egyptians reportedly suffered heavy casualties. The Mamluk center and left wings under the command of the emirs Salar and Baibars al-Jashnakir, together with their Bedouin irregulars, then engaged the Mongols. The Mongols continued their pressure on the right flank of the Egyptian army. Many of the Mamluks believed that the battle would soon be lost. The Mamluk left flank, however, had remained steady. Qutlugh-Shah then went to the top of a nearby hill, hoping to watch the victory of his forces. While he was issuing orders to his army, the Egyptians surrounded the hill. This led to heavy, bitter fighting, and the Mongols suffered many casualties on the hill. The next morning, the Mamluks deliberately opened their ranks to allow the Mongols to flee to the river Wadi Arram. When the Mongols arrived at the river, they were able to receive reinforcements. However, while the Mongols were taking on badly needed supplies of water for themselves and their horses, the Sultan was able to attack them from the rear. The subsequent fighting, which lasted until noon, was vicious. By the next day, the battle was over.[8] AftermathAccording to the medieval Egyptian historian Al-Maqrizi, after the battle, Qutlugh-Shah reached the Ilkhan Ghazan at Kushuf, to inform him of the defeat of his forces. It was reported that Ghazan, upon hearing the news, had gone into such a rage that it resulted in a nose bleed.[9] Messages were sent to Egypt and Damascus to tell of the victory, and the Sultan went to Damascus. While the Sultan was in Damascus, the Mamluk army kept chasing the Mongols as far as Al-Qaryatayn. When the Sultan returned to Cairo, he entered through the Bab al-Nasr (Victory Gate) with chained prisoners of war. Singers and dancers were called from all over Egypt to celebrate the great victory. Castles were decorated and the celebrations lasted many days. Notes

References

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||