|

Action of 22 October 1917

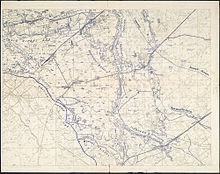

The action of 22 October 1917 was an attack during the Third Battle of Ypres in the First World War by the British Fifth Army and the French First Army against the German 4th Army. British attacks had been repulsed at Passchendaele by the 4th Army at the Battle of Poelcappelle (9 October) and the First Battle of Passchendaele (12 October). While the British waited for another dry spell and the completion of plank roads up to the new front line, the Canadian Corps and fresh British divisions were transferred to Flanders by the British Expeditionary Force (BEF). The Fifth Army planned an attack to capture the rest of Polecappelle and to close up to Houthulst Forest, while the French 36er Corps d'Armée on the left attacked simultaneously. The plan was for the Fifth Army to provide a defensive flank for the Second Army and to keep pressure on the defenders. It was important to prevent the Germans from transferring troops from Flanders against the French during the Battle of La Malmaison on the Aisne (23–27 October) and to stop local redeployments before the Canadian attack towards Passchendaele, due on 26 October. On 22 October, the 18th (Eastern) Division attacked the east end of Polecappelle, the 34th Division attacked further north, between the Watervlietbeek and Broenbeek streams and the 35th Division attacked northwards into Houthulst Forest, supported by an attack by the right-hand regiment of the French 1st Division. Poelcappelle was captured but the attack at the junction between the 34th and 35th divisions was repulsed and German counter-attacks pushed back the 35th Division in the centre. The French regiment captured its objectives and later sent parties to scout the southern edge of Houthoulst Forest and take crossings over the Corverbeek on the left flank. Attacking on ground cut up by bombardments and soaked by rain, the British struggled to advance in places and lost the ability to move quickly to outflank pillboxes. Troops of the 35th Division reached the fringes of Houthulst Forest but were repulsed elsewhere. German counter-attacks after 22 October, at an equal disadvantage, resulted in equally costly failures. The 4th Army was prevented from transferring troops away from the Fifth Army and from concentrating its artillery-fire on the Canadians, as they prepared to begin the Second Battle of Passchendaele (26 October – 10 November 1917). BackgroundStrategic developmentsAt a meeting on 13 October, Haig and the army commanders agreed that no more attacks could be made until the rain stopped and roads had been built to move forward the artillery and make bombardments more effective. Haig wanted to continue the offensive until Passchendaele Ridge as far as Westroosebeek had been captured and to support the forthcoming French attack at La Malmaison, by keeping the Germans pinned down in Flanders. Haig also mentioned an attack by the Third Army (General Sir Julian Byng) at Cambrai, to take place before winter; Byng wanted operations to continue in Flanders to increase the chance of success in Artois. Despite the dreadful state of the ground in the Ypres Salient, the offensive was to continue.[1] Liaison, artillery and engineer staff officers and members of the BEF Operations Section flew over the battlefield to report on the state of the ground.[1] The Fifth Army was to receive the 1st Division and the 63rd (Royal Naval) Division in time to attack on 22 October.[2] XVIII Corps was to capture the rest of Poelcappelle; on the left of XVIII Corps, XIV Corps was to attack northwards into Houthulst Forest, to move the left flank of the Fifth Army onto higher ground in the southern fringe of the forest and to advance the line eastwards along the Vijfwegen Spur. The French First Army would guard the left flank of XIV Corps by attacking towards Houthulst Forest with two divisions. On the right flank of the Second Army, the I Anzac Corps and X Corps were to protect the right of the Canadian Corps with attacks down the Bassevillebeek and Gheluvelt spurs and towards Polderhoek Château, to force the Germans to spread their artillery-fire over a wider area.[3] British tactics, late 1917 German defences opposite the Fifth Army After the Battle of the Menin Road Ridge on 20 September, British attack planning had reached a stage of development where orders were reduced to a formula. On 7 November, the written Second Army operation order for attacks needed less than a page of text. Corps staffs devised details and more discretion was granted to divisional commanders than in 1915 and 1916. The tactical sophistication of the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) had increased during the battle but the chronic difficulty of communication between front and rear during an attack could not be resolved. Due to the German system of pillbox defence and the impossibility of maintaining linear formations on ground full of flooded shell-craters, waves of infantry had been replaced by a thin line of skirmishers leading small columns. The rifle was re-established as the primary infantry weapon and Stokes mortar fire was added to creeping barrages. "Draw net" barrages were introduced, where before an attack, field guns began a barrage 1,500 yd (1,400 m) behind the German front line, moved the barrage towards the German front line and back again several times.[4] German defensive tacticsErich Ludendorff, the Quartermaster general (Erster Generalquartiermeister) of the German armies, over-ruled Feldmarschall Rupprecht, Crown Prince of Bavaria, the commander of Army Group Rupprecht of Bavaria (Heeresgruppe Kronprinz Rupprecht von Bayern) and General Friedrich Sixt von Armin, the 4th Army commander, over the defensive tactics to be used after the disaster of the Battle of Broodseinde on 4 October. Ludendorff insisted on the establishment of an outpost line (Vorfeldlinie) in front of a Vorfeld (outpost area) 500–1,000 yd (460–910 m) deep, to be occupied by a few sentries and machine-guns. When the British attacked, the sentries were swiftly to retire from the Vorfeld to the main line of resistance (Hauptwiederstandslinie) behind it and the artillery was quickly to bombard the Vorfeldlinie. The tactic was expected to give rear battalions of the Stellungsdivisionen (ground holding divisions) and Eingreifdivisionen (specialist counter-attack divisions), time to get to the Hauptwiederstandslinie. If an immediate counter-attack (Gegenstoß) was not possible, a Gegenangriff (methodical counter-attack) was to be conducted after a delay of 24–48 hours to make time to prepare the artillery, infantry and supporting aircraft.[5] A Stellungsdivision held a 2,500 yd (1.4 mi; 2.3 km) front to a depth of 8,000 yd (4.5 mi; 7.3 km), half the area held in June, because of the difficulties caused by the weather, devastating British artillery-fire and German infantry casualties. For camouflage (the empty battlefield, die Leere des Gefechtsfeldes) shell-holes were occupied rather than trenches; Stellungsdivision battalions were relieved after two days and divisions every six days.[6] Sixt von Armin wrote an order for the new tactics on 11 October. The Battle of Poelcappelle (9 October) showed that where British attacks were limited, a Stellungsdivision could repulse the attack unaided or regain positions, when reinforced by its Eingreif division. Where attacks had succeeded, even a fresh Stellungsdivision and its Eingreif division were incapable of re-capturing all of the lost ground. Sixt von Armin wrote that Stellungsdivisionen must not be left short of men and that Eingreif divisions must be used sparingly. After an attack, the foremost troops were reduced to a remnant with no command system or depth of defence, which could only be remedied by relieving them with fresh units. Between battles, casualties from the incessant British artillery-fire and the high rate of sickness caused almost as much wastage; formations had to be relieved quicker.[7] The Stellungsdivisionen held sectors that were too wide for swift replacement, because of the tempo of British attacks; Eingreif divisions had to be ready to swap places to enable frequent reliefs. A quicker rotation of divisions would limit the exhaustion of the infantry and make sure that the troops defending an area were familiar with the ground. The relief system could apply only to infantry and engineers because the artillery had been divided; two-thirds remained in emplacements and one third was kept mobile to support counter-attacks. Sixt von Armin ordered that the new tactics were to apply to Gruppe Staden in the north, Gruppe Ypern in the centre and the right flank division of Gruppe Wijtschate to the south. Divisional reliefs should be accomplished in one night; Eingreif divisions were to keep a third of their troops close to the front and the rest in reserve, only to advance to the battlefront after a British attack had started. If the Eingreif troops were needed, then at the minimum, the battalions engaged were to be relieved by fresh troops. The new Vorfeld defence system was to be explained in detail to the troops before they went into action. Sixt von Armin concluded with a warning that more troops were straggling to the rear and that a cordon should be used to prevent soldiers from moving beyond without written authority. Punishments were to be inflicted for abandoning posts and announced to the troops.[8] First Battle of Passschendaele Map showing wet areas near Passchendaele village, in blue On 12 October, the defensive effort of the 4th Army had been more effective than expected by the British, although the new Vorfeld tactic did not prevent the Germans from losing ground. The main attack on Passchendaele village had been another costly failure for the British and the ground from Broodseinde, northwards to Houthulst Forest, was strewn with their dead and wounded. The German divisions that fought on 9 October had not needed relief before the attack on 12 October and Fifth Army casualties from 9 to 14 October had been almost 10,000 men.[9] Opposite Poelcappelle, the German 18th Division had managed to hold most of its ground, after committing all of its reserves.[10] The 4th Army HQ considered that the Allied advance in the north to be less dangerous than that towards Flandern II Stellung, the defensive position between Passchendaele and Drogenbroodhoek but a fresh division was moved to the area from Westrozebeke.[11] Ludendorff changed his mind about holding Passchendaele Ridge, believing that the British had only fourteen days before the autumn weather ended the battle and ordered Rupprecht to stand fast.[10] At a conference on 18 October, Sixt von Armin and his chief of staff, Colonel Fritz von Loßberg preferred to hold the remaining defences of Flandern I Stellung and Flandern II Stellung, rather than retire to Flandern III Stellung.[12] PreludeGerman defensive preparationsOn the nights of 14/15, 16/17, 18/19 and 19/20 October, the Germans conducted gas bombardments on the Hanebeek, Zonnebeke and Steenbeek valleys. Blue Cross gas (sneezing gas, diphenyl chloroarsine) shells were fired to make men take off their gas masks, making them vulnerable to the following Yellow Cross shells (mustard gas, dichloroethyl sulphide) which caused blisters, throat and eye injuries. There were few Allied fatalities but thousands of infantry, gunners and men in working parties were contaminated by the mustard gas and needed medical treatment. Opposite XIV Corps, was Gruppe Staden (Group Staden, a corps headquarters) which administered the defence of the area and commanded the divisions holding it, which were moved into the area for a time and were then relieved by fresh divisions. In mid-October, the divisions in Gruppe comprised the 58th Division, recently arrived from the Eastern Front, parts of the 3rd Division from Marine-Korps-Flandern (Admiral Ludwig von Schröder) and the 26th Reserve Division.[13] Units of the 58th Division had begun to move up through Houthulst Forest to bolster the 119th Division on 13 October, under frequent British and French artillery and gas bombardment. On 20 October, the Allied preparatory bombardment shifted to the German support lines and two soldiers, trapped in an overturned pillbox since 15 October, were rescued. Next day, German artillery bombarded the front of Gruppe Staden to disrupt the massing of French and British troops for another attack.[14] British offensive preparations

The weather improved in mid-October, rainfall diminishing to an average of 1.4 mm per day, which prevented the dreadful condition of the ground from deteriorating further. German artillery bombardments increased on plank roads and other attack preparations, which were easily visible from Passchendaele Ridge. From 14 October, the Germans bombarded the Steenbeek Valley almost nightly with gas shell and during the night German aircraft bombed targets behind Allied lines. Further back, British artillery positions and infantry bivouacs were covered in mustard oil and had to be quarantined. Despite the nightly gas bombardments and frequent day bombardments, new roads and artillery emplacements were built on time and from 21 October, British artillery began wire-cutting and destructive bombardments on German pillboxes and blockhouses. Daily preparatory barrages were fired deeper into the German defences.[16] XVIII CorpsAfter the First Battle of Passchendaele (12 October) no man's land ran through the middle of Poelcappelle, where a few stones were still standing. From the west, the Langemarck road had almost disappeared and intelligence officers searched shell-holes for foundations to determine the route. Movement to the front line was via 5 mi (8.0 km) of duckboard track; up and down lines had been laid but congestion and German artillery-fire meant constant interruptions to movement. On 12 October, the 55th Brigade of the 18th (Eastern) Division had attacked Poelcappelle in snake formation and been repulsed after every piece of the attackers' equipment containing moving parts had been jammed by mud. Another downpour fell on the night of 12/13 October and some units received no food for two days. Experiments with Canadian Yukon packs, on which 120 lb (54 kg) could be carried, revealed that the lack of footing made them useless. Exchanges of artillery-fire were continuous, increased in severity and on 17 October, German artillery bombarded the 18th (Eastern) Division positions for 15 minutes every hour, from 4:00 a.m. until daybreak.[17] XIV CorpsThe 34th Division (Major-General Sir Lothian Nicholson) relieved the 4th Division from the night of 12/13 October. It was a two-hour walk to reach Langemarck through a morass of shell-holes, destroyed equipment and corpses, along duckboards which had been advanced within 1,000–1,500 yd (910–1,370 m) of the front line. Two battalions of the 102nd Brigade were bombed during the night of 16/17 October and lost 106 casualties. The division took over the 19th (Western) Division front to the north and 250 yd (230 m) of the 35th Division front on the night of 18/19 October. On 20 October, the 15th Battalion and 16th Battalion Royal Scots relieved the 101st Brigade, the 16th Battalion on the left, next to the right-flank battalion of the 35th Division, losing both commanding officers to gas poisoning in the process. Because of map discrepancies over the positions of the front line and the artillery barrage line, it was arranged that both battalions would fall back for 200 yd (180 m) before the attack, a difficult manoeuvre on ground with no landmarks, at night and under bombardment. The attacking troops continued to suffer losses to German artillery-fire for the day and the night previous to the attack.[18] On 16 October, the 104th Brigade of the 35th Division (Major-General Reginald Pinney) took over from the 3rd Guards Brigade at the Ypres–Staden railway to 250 yd (230 m) south-east of the Faidherbe crossroads, with the French 2nd Division on the left. Movement towards the front line was via the Clarges Street and Hunter Street tracks, which wound around flooded shell-holes and the morasses of the Steenbeek and the Broenbeek stream. German artillery filled the depressions with high explosive (HE) and gas shell on most nights. A light railway built along the bed of the Ypres–Staden railway had reached Langemarck station and carried heavy artillery ammunition, equipment and engineer stores. Supplies were carried up the tracks and packhorses moving ammunition used a road further to the west. The area was so waterlogged that many German heavy shells failed to explode or were stifled by the mud. On 18 October, the 106th Brigade took over from the 104th Brigade on the right flank and on 20 October, the 104th Brigade took over from Aden House to the Cinq Chemins (Five Ways) crossroads; on the left, the 105th Brigade held the line from Cinq Chemins to a pillbox north of Louvois Farm, with the French 1st Division on its left flank. Houthulst Forest lay north of Pilckem, about 4 mi (6.4 km) ahead, an irregular-shaped wood of about 1,500 acres (610 ha), cut by tracks, ditches and fences into 10–20 acres (4.0–8.1 ha) sections, much of which was overgrown. The British artillery bombarded German positions all day on 21 October, to which the German artillery replied; a soldier from the German 58th Division was captured, which was taken by the British to mean that the Germans had been reinforced. The night of 21/22 October was very cold; it began to rain at midnight and continued intermittently for the rest of the day.[19] Air operations A Sopwith Camel of the type used at the Third Battle of Ypres In the better weather before 22 October, the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) flew many reconnaissance and artillery-observation sorties. On 20 October, 45 aircraft attacked Rumbeke airfield; eleven Sopwith Camels carried bombs, with eight more as close escort. A squadron of 19 Camels attacked from the east to catch any German aircraft in the air and seven Spad VIIs flew high above to cover the attackers. The Camels dropped 22 bombs from low altitude and then strafed the airfield from so low that two Camels touched the ground with their wheels. The escorts claimed seven German aircraft shot down out of control for the loss of two aircraft; as the Camels flew home, they attacked targets of opportunity. On the night of 20/21 October, Ingelmunster railway station and airfield and Bisseghem aerodrome were bombed. On 21 October, reconnaissance aircraft took 1,304 photographs and artillery-observation crews directed destructive bombardments on 67 German artillery batteries. Bombing raids were made on Abeele and Heule airfields and in dogfights with German fighters, ten aircraft were claimed shot down, for a loss of 19 British aircrew casualties. During the night, British bombers attacked Ingelmunster, Abeele, Marcke, Bisseghem and Moorslede aerodromes and the railway station at Roulers.[20] British planThe artillery of the Second and Fifth armies were to open fire at zero hour, to mislead the Germans about the limited nature of the Fifth Army attack.[21] At Poelcappelle, no man's land was through the middle of the village and was so narrow that a temporary withdrawal was necessary for the artillery to bombard the area. The 18th (Eastern) Division was to attack with the 53rd Brigade, one battalion to capture an intermediate objective (dotted blue line) and a second battalion to take the final objective (blue line). The attack was to have three phases, in which three companies of the 8th Battalion, Norfolk Regiment were to advance into the village and capture the German pillboxes at the Brewery, as the fourth company attacked the Helles Houses pillboxes 350 yd (320 m) from the Brewery, by crossing into the 34th Division area and attacking from the north. After a two-hour pause, the second phase would begin, with three companies of the 10th Battalion Essex Regiment leap-frogging through the Norfolk positions, following a creeping barrage to the final objectives from Meunier House to Nobles Farm, 500 yd (460 m) beyond the Brewery. If the attack succeeded, the third phase would begin with the fourth Essex company near Gloster Farm on the right flank, advancing to capture the Beek House blockhouse.[22] The 34th Division was to attack up the Watervlietbeek and Broenbeek valleys on a 2,000 yd (1,800 m) front, from the north end of Poelcappelle to the Ypres–Staden railway. The 102nd Brigade was to attack on the right flank from Poelcappelle to the Watervlietbeek and two battalions of the 101st Brigade were to attack north of the stream. On 21 October, the positions north of the Watervlietbeek had been hit by British artillery, causing 80 casualties.[23] The adjoining companies of the 15th and 16th Royal Scots had to assemble 200 yd (180 m) behind the front line shell-hole positions. With no landmarks and deep mud, assembling at night and under German artillery-fire, the two battalions managed to deploy on a two-company front about 1,000 yd (910 m) wide from Aden House to Gravel Farm, with two companies in support. The advance was to pivot on the right flank of the 15th Royal Scots, until the left flank of the 16th Royal Scots had swung forward to the cinq Chemins (Five Ways) crossroads, in touch with the right flank of the 35th Division. The distance was about 1,100 yd (1,000 m) and on the right side of the 15th Royal Fusiliers, the next company held a front of about 350 yd (320 m) to Bower House and was to stay in position to fire on the Germans opposite in support of the troops on either flank.[18] On the left flank, the 35th Division was to attack on a similar front 800 yd (730 m) forward into Houthulst Forest. The objective was about 2,500 yd (1.4 mi; 2.3 km) wide, requiring a divergent advance to the objective from the cinq chemins crossroads westwards to Maréchal Farm, thence to a position 400 yd (370 m) north of Panama House. The 104th Brigade was to attack on the right flank with two battalions, the other two battalions in support and a battalion from the 106th Brigade in reserve. On the left, the 105th Brigade was to attack with two battalions, one in support and one in reserve.[24] The Canadian Corps was to support the attack with a gas bombardment on German artillery opposite the Fifth Army and a 4.5-inch howitzer gas bombardment on German shell-hole positions opposite XVIII Corps.[25] In the 9th (Scottish) Division sector adjacent to the Canadians, the XVIII Corps Cyclist Battalion was to conduct a feint, using dummy figures, to assist the attack by the 18th (Eastern) Division.[26] The French XXXVI Corps was to guard the left flank of XIV Corps with Operation B, in which the 201st Infantry Regiment of the 1st Division was to advance northwards on a line from the Faidherbe crossroads next to XIV Corps, to the Putois (Polecat) crossroads, the Belette (Weasel) crossroads and ferme Papagoed (Butterfly Farm), pivoting on the left to a farm at point 86.15 on the right and ferme Jean Bart on the left, a line facing roughly north-west. On the night of 13/14 October, the 133rd Division relieved the 51st and 2nd divisions; from 16 October, the 1st Division and 51st Division replaced the 133rd Division and two days later the 1st Division took over the line from the junction with XIV Corps at Point 83.08 and the Corverbeek on the left, with advanced posts at ferme Jean Bart and the Belette and Putois crossroads, ready to attack.[27] AttackPoelcappelleThe attacking troops moved up to the front line on the night of 21/22 October, through the morass of the Steenbeek with respirators at the alert position on their heads, having already been bombarded with HE and gas shell. The 8th Norfolk took post in shell-holes marked with tapes by 1:00 a.m. when it began to rain and the 10th Essex were ready by 2:00 a.m. The British barrage began at 5:35 a.m. and eight minutes later began to creep forward at 100 yd (91 m) per minute. The 8th Norfolk advanced through the village against slight resistance and captured the pillboxes at the Brewery. One hour later, the 10th Essex advanced, C Company on the right, A Company in the centre and B Company on the left. A machine-gun 200 yd (180 m) to the west of Helles House, pinned down B Company and part of A Company, until a party outflanked and captured the post. The Essex then advanced to the Norfolks and found cover amidst the ruins of the village and shell-holes. German artillery-fire had increased, the dreadful condition of the ground made it difficult to vacate the area being bombarded and C Company arrived at the jumping-off position severely depleted, their weapons already jammed by mud.[28] At 7:35 a.m., the barrage began to creep forward again and the 10th Essex companies leap-frogged the 8th Norfolk, suffering little machine-gun fire but under constant German artillery-fire. C Company was so diminished that it attacked only Meunier House, 500 yd (460 m) south-east of Poelcappelle, the German garrison retreating before the British arrived. In the centre, A Company captured its objective and B Company took Nobles Farm. At 8:00 a.m., the troops were digging in from Meunier House to Nobles Farm but C and A companies were down to only 80 men, most of the Lewis gun ammunition had been fired and weapons were still clogged with mud. Troops from the 11th Royal Fusiliers went forward to Meunier House at 10:00 a.m. and others took over at Nobles Farm. On the right flank, D Company received the success signal from C Company and attacked at 8:35 a.m. through much artillery-fire but little infantry opposition. By 9:00 a.m., the company was consolidating posts in flooded shell-holes to the east of Beek House on the Lekkerboterbeek. A patrol went forward to Tracas Farm 200 yd (180 m) further on, which was empty but under British artillery-fire; a message to lift the fire was received quickly and a platoon occupied the position. At 4:30 p.m., the German bombardment increased, particularly from Nobles Farm to the Westroosebeke road and infantry began to work down the road from Spriet. The Germans deployed to attack 200 yd (180 m) short of the new British positions and trickled forward from shell-hole to shell-hole but were repulsed by the small-arms fire of the 10th Essex.[29] Houthulst Forest34th Division Map Showing Allied progress in the Ypres Salient, 1917 At 5:35 a.m. the British barrage fell and appeared dense and accurate; in the 34th Division area, the composite Northumberland battalion captured Requette Farm about 500 yd (460 m) forward and the rest of the battalion closed up to the objective as far as Rubens Farm. The 15th Royal Scots advanced on a two-company front from Gravel Farm and Turenne Crossing on the Ypres–Staden railway, towards the first objective 300 yd (270 m) away, near huts along by the Vijfwegen road and the Broenbeek. The two support companies waited at Taube Farm, 700 yd (640 m) back and the attacking battalions were hit by machine-gun fire from several directions, particularly from pillboxes on the north bank of the Broenbeek. German artillery-fire began after ten minutes but only a few shells landed near the attackers, sending up water spouts but Taube Farm was hit accurately and half of the two support companies were unable to move forward.[a] As A Company neared the first objective, machine-gun fire from the pillboxes along the Broenbeek surrounded by uncut barbed wire, became intense. The survivors struggled through the mud until driven under cover in shell-holes near the huts; attempts to cut through the wire and attack the position failed.[31] The 16th Royal Scots were hit by the artillery of both sides as they assembled and had only enough men for one wave, which advanced at zero hour. The troops on the right flank were caught in machine-gun fire from the huts near the 15th Royal Scots, lost much of their firepower when weapons were jammed by mud and were forced back by a counter-attack, one party disappearing near Turenne Crossing. On the left flank, C and D companies reached the Six Roads pillboxes, where the advance was stopped by machine-gun fire. The troops returned fire to cover the Manchester battalion of the 35th Division on the left, as they tried to outflank the pillboxes. The attempt was also stopped by uncut wire but a party of the Royal Scots captured a pillbox and took six prisoners. At 7:00 a.m., a German counter-attack was repulsed by rifle-fire but after holding on despite mounting casualties, the remaining 16th Royal Scots and Manchesters retreated to a point east of Egypt House. Communication with the rear had been almost impossible, unburied telephone cables being cut early on, runners being slowed to a crawl by the mud and the area being bombarded continuously all day with HE and gas shell. During the night, the 10th Battalion Lincolnshire Regiment and the 11th Battalion Suffolk Regiment relieved the attacking battalions.[32] 35th DivisionThe 104th Brigade battalions moved forward to tapes laid out in no man's land at 2:00 a.m. to evade the dawn bombardment by the German artillery of the British front line. The advance began at 5:35 a.m. behind a creeping barrage moving at 100 yd (91 m) in eight minutes. The 23rd Manchesters on the right flank lost touch with the 16th Royal Scots of the 34th Division which had drawn back to avoid bombardment from both artilleries. The advance continued for about 0.5 mi (0.80 km) to the first objective, where machine-gun fire from huts on both flanks was received, all but fifty men of the leading waves becoming casualties. The survivors made a slow withdrawal to the start line.[33][b] The 20th Lancashire Fusiliers were ordered forward and the 17th Royal Scots moved up to a line from Koekuit to Namur Crossing. On the left, the 17th Lancashire Fusiliers followed the barrage along a road from Colombo House to Maréchal Farm, with the 16th Battalion Cheshire Regiment on the left.[34] The 17th Lancashire reached Colombo House and by 6:45 a.m. had reached the final objective. A company of the 18th Lancashire which was to fill the gap created by the diverging advance of the attacking troops strayed to the left flank, which caused a delay as they moved across to the right. The company advanced into Houthulst Forest but was fired on by machine-guns on the right flank, which was unsupported and forced to retreat to the fringe of the woods. Other troops had reached their objective along Conter Drive, which ran through Houthulst Forest past Maréchal Farm to Vijfwegen, in touch with the 17th Lancashire. To cover the right flank, two companies of the 20th Lancashire went forward and at about 10:00 a.m. took over from 100 yd (91 m) beyond angle Point to 200 yd (180 m) beyond Aden House on the right of the 17th Lancashire; no troops of the 34th Division could be found, except for five wounded men. By noon, the brigade held a line from Maréchal Farm, a short stretch of Conter Drive and back to some huts 500 yd (460 m) to the north-east of Angle Point and thence to Aden House.[35] The 105th Brigade troops formed up with the support companies in the front line and the attacking companies in shell-holes further back. The advance began behind the creeping barrage but bad going immediately slowed the advance. On the right flank, the 16th Cheshire managed to advance faster and reached the objective at Maréchal Farm but the advance in the centre and on the left flank was stopped by machine-guns in pillboxes inside the forest, 500 yd (460 m) to the north-west of Colombo House. The pillboxes were captured but the advance was stopped again just beyond and the troops consolidated, in touch with the troops at Maréchal Farm and the 14th Gloucester on the left flank as other troops garrisoned Colombo House. The 14th Goucester on the left had reached the first objective and taken Panama House by 6:15 a.m. except on the left flank, where a fortified farm had to be rushed; on the right flank a pillbox beyond the objective was captured at 7:45 a.m. Touch was regained with the 16th Cheshire and a support platoon filled the gap. The 17th Battalion West Yorkshire Regiment moved up to Koekuit as a reserve for the 105th Brigade.[36] French 1st DivisionThe German 40th Division and elements of the 58th Division held the line opposite the French, north of Mangelaere, where the 201st Infantry Regiment (General Marindin) of the 1st Division, was to advance on a line from the Faidherbe crossroads next to the British to ferme Papagoed (Butterfly Farm). The regiment was to capture several redoubts towards the farm at point 86.15, north of the Faidherbe crossroads on the right, to the ruins of Jean Bart Farm on the left. The preliminary bombardment was so effective that the French objectives were quickly taken, despite machine-gun fire from ferme Surcouf on the left.[37] The French joined in the British attack east of Veldhoek and helped to reduce a number of pillboxes; resistance was encountered at Panama Farm, north-east of Veldhoek but this was soon overrun. In the afternoon, patrols, often up to their waists in water, reached the fringes of Houthulst Forest, 1,100 yd (1,000 m) from the jumping-off point and captured two field guns and several prisoners.[38] The two regiments of the 1st Division in reserve sent parties forward to capture crossings along the Corverbeek on the left.[39] A British platoon had been provided for liaison with the 201st Infantry Regiment and when the French reached their objectives, Marindin sent two companies to form a defensive flank from Louvois Farm to Obtuse Bend.[40] German counter-attacksAfter a lull from 2:00–4:30 p.m., German troops attacked on the left side of the 16th Cheshire and overran the British defences. The survivors of the three Cheshire companies and a company of the 15th Sherwood Foresters were almost surrounded, retreated about 100 yd (91 m) from Houthulst Forest but were then pushed back to the start line. The retirement uncovered the left flank of the party in Maréchal Farm, which formed a defensive flank along the road back to Colombo House, with the right flank ahead of the farm. As the left flank of the Cheshires moved back, the left side of the 17th Lancashire Fusiliers conformed at 6:00 p.m., moving back to the support line under the impression that they were being left exposed in a salient. The retirement of the 17th Lancashire Company did leave Z Company of the Cheshires beyond Maréchal Farm isolated and it withdrew to Colombo House; the 18th Lancashire prolonged the line closer to the huts on the right flank. After the German counter-attack and the confusion on the British right, only the 14th Gloucester on the left flank next to the French remained on the final objective, in this area, the German attack was caught in a British barrage and was repulsed.[41]  German diagram of Württemberg division positions, October 1917 The 14th Gloucester refused its right flank (angled it backwards) to link with the 16th Cheshire and a party from the 15th Sherwood Foresters filled the gap. As the German counter-attack progressed, troops assembled opposite the 17th and 18th Lancashire, who called for an SOS bombardment; when the Germans attacked they were repulsed with many casualties. It became much harder to communicate with the rear because of German standing barrages behind the British front line and the methodical German bombardment of battalion headquarters. Units began to mingle, the attacking battalions began to tire and the weather deteriorated, which made movement even harder. Despite this, parties took tea and rum forward for the troops in the front line. The German counter-attacks ended and the 23rd Manchester was relieved by the 20th Lancashire Fusiliers. A battalion was sent forward to Koekuit and the attacking battalions of the 105th Brigade were also relieved, the line being held by the 15th Cheshire with the 15th Sherwood Foresters in support.[42] 23–24 OctoberThe machine-gun nests 750 yd (690 m) beyond Aden House were blamed for the collapse of the attack on the right flank of the 35th Division and the casualties in the 23rd Manchester. At 2:00 a.m. on 23 October, a party of 22 men from the 20th Lancashire Fusiliers struggled through the mud to reach the position, which was 350 yd (320 m) beyond the wire that had blocked the advance of the 16th Royal Scots and the Manchester battalion, the day before. The party managed to surprise a machine-gun post but the noise alerted the Germans who sent up SOS flares, machine-gunned and bombarded the area, which caused many casualties in the raiding party as it retired. At 5:30 a.m. a German counter-attack on the left flank at the junction of the 105th Brigade and the French 201st Regiment was repulsed by small-arms fire and an SOS barrage. About twenty prisoners were taken and it was thought that many more German soldiers were shot from behind before they could surrender.[43] The British infantry had a shrapnel bombardment fired over the shell-holes where many German troops had taken cover and killed at least forty men. On the night of 23/24 October, the 15th Cheshire returned to the first objective by advancing 200 yd (180 m) to the north of Colombo House on a line 500 yd (460 m) west of the Maréchal Farm road, which filled in part of the re-entrant caused by the British retirements during the first German counter-attack. At 5:00 p.m. another German counter-attack began opposite the 19th Battalion Durham Light Infantry and the 15th Cheshire, which was being relieved. From 300–400 German infantry advanced behind a creeping barrage but the attack was repulsed by small-arms fire and artillery, 60–70 Germans being killed and several prisoners taken.[44][45] Air supportThe attack on 22 October was conducted in a rainstorm which grounded many RFC aircraft until the afternoon but the advance of the British infantry was observed by contact-patrol aircraft crews. Especially in the afternoon and evening, fighter pilots attacked German troops in trenches and shell-holes. Machine-gun nests and artillery batteries were also attacked and two battalions of infantry moving along the Houthulst–Staden road were caught by a pair Camel pilots and scattered. A bomber squadron attacked Hooglede village, where many resting soldiers were billeted.[46] German aircraft, flying at low altitude, attacked the positions of the 35th Division and one aircraft followed a British contact-patrol aircraft. When troops responded to a call for flares, the German pilot dropped signal lights on them, marking their position for the German artillery. The British sent forward an 18-pounder anti-aircraft gun to Koekuit, to engage German aircraft but it had little effect.[47] AftermathAnalysisThe 18th (Eastern) Division objectives had been reached and another 250 yd (230 m) taken at Tracas Farm.[48] Poelcappelle had mainly been defended by artillery and the 18th (Eastern) Division captured the east end of the village ruins, where the Germans had repulsed two previous attacks. In 1996, Prior and Wilson wrote that the attack had succeeded with 300–400 yd (270–370 m) of ground being gained but only because the Germans had already retired.[49] In 2014, Robert Perry wrote that the weather and the deplorable condition of the ground had led to the British infantry having to lie down cold and wet, in waterlogged shell-holes, under German bombardment. Captured pillboxes and blockhouses were methodically bombarded by the German guns with HE and gas shell, making communication between the British front line and the rear almost impossible. Snipers and machine-gunners firing from concealed positions among trees in Houthulst Forest caused a stream casualties and counter-attacks from the forest showed that the German infantry would resist vigorously.[50] The 34th Division attacked at the point where the British front line swung round from north–south to east–west; in the centre of the attack were five German pillboxes, which channelled the attack to either side. The Germans fought with skill and determination from well-fortified and camouflaged positions. Counter-attacks by the German 3rd Division and the 58th Division defeated the 34th Division attack, which was forced back to the start line.[51] In 1921, the 35th Division historian, Harry Davson, wrote that the loss of contact with the 34th Division on the right had allowed German troops to retreat, then fire on the 35th Division troops from the flanks and from behind. German pillboxes near some huts beyond Aden House had a commanding view and caused many casualties. Despite the care taken in planning the creeping barrage, some units advancing through undergrowth found it too fast and others in the open thought it was too slow. The troops had either lost the barrage or plunged forward so quickly that they reached the objective in an exhausted state. Once the advance had reached its limit, German aircraft strafed the British troops from low altitude and German troops used the trees in Houthulst Forest beyond the British objective for cover, sniping at the British despite a shrapnel barrage, until the 35th Division was relieved. Potte Drief, a road running parallel to Conter Drive about 200 yd (180 m) away, had been camouflaged and the Germans could move along it unseen.[52] Perry wrote that the XIV Corps attack had kept German troops in the area and prevented the German artillery from concentrating its fire on the Canadian Corps front.[45] From 22 to 23 October, the 35th Division artillery and attached brigades fired about 66,500 rounds of ammunition. The weather deteriorated from 22 to 24 October with about 5.5 mm of rain each day, which soaked the ground again. After 22 October, there was a lull until the Second Battle of Passchendaele began on 26 October.[53] On 23 October, the German command system was altered to put the Eingreif division under the authority of the Stellungsdivision commander, regardless of rank. Troops of the Eingreif division were put under the commanding officer (Kampf-Truppen-Kommandeuer, KTK) of the front battalion, which created a two-division unit.[54] On 25 October, Rupprecht wrote that there was only one month of campaigning weather left but that if the weather held, the British attacks would be the most effective of all. In 2007, Jack Sheldon wrote that although the German troops defending Passchendaele, who managed to survive the massed British artillery-fire, had performed superlatively, their morale could not withstand the realisation that the British bite and hold system was irresistible. By the end of the month, the situation for the Germans on the flanks opposite Passchendaele had eased. The Fifth Army attack and attacks on the southern flank of the salient at Gheluvelt had been contained as the advance towards Passchendaele had continued. Rupprecht and Sixt von Armin proposed to counter-attack the British north of Broodsende but the divisions of the 4th Army were rapidly being exhausted by the constant fighting, artillery bombardments, air attacks and the weather; the rapid sequence of British attacks made it impossible to accumulate a reserve to counter-attack.[55] CasualtiesFifth Army casualties for 22 October were 60 men killed, 398 wounded and 21 men missing; approximately 125 German troops were captured.[21] The 34th Division spent sixteen days in the line during October and had casualties of 303 men killed, 1,089 wounded and 405 men missing. From 10–27 October, 886 men were evacuated sick.[56] From 18–29 October, the 35th Division had casualties of 368 men killed, 1,734 wounded and 462 men missing. The 35th divisional artillery and attached units lost 27 men killed, 165 wounded and 2 men missing; 85 prisoners were taken from 18–25 October.[47] Subsequent operationsAfter 23 October, the French prepared for Operation Y, to occupy all the ground from Houthoulst Forest to Blankaart Lake as the British advanced to Passchendaele and Westroosebeke. The 133rd Division moved into line between the 1st and 51st Divisions, from Martjewaart to Saint-Jansbeek and ferme Carnot.[37] On 26 October, XVIII Corps attacked the defences of Flandern I Stellung, a mixture of pillboxes, blockhouses and fortified farmhouses, with the 63rd (Royal Naval) Division and the 58th (2/1st London) Division, in support of the Canadian Corps to the right on Passchendaele Ridge. The divisions attacked up the Lekkerboterbeek towards Westrozebeke but deep mud reduced the advance to a crawl. The creeping barrage moved forward too fast, rifles clogged with mud and the British fell back to the start line where they could or were surrounded by the Germans and overrun. XIV Corps attacked with the 57th (2nd West Lancashire) Division and the 50th (Northumbrian) Division but the ground was in a dreadful condition; on the left flank the French 1st Division and the 133rd Division managed a short advance into the south-west corner of Houthulst Forest. The attacks cost the Fifth Army 5,402 casualties, 949 in the 63rd Division, 1,361 in the 58th Division, 1,634 in the 57th Division and 1,458 men of the 50th Division.[57] Notes

Footnotes

ReferencesBooks

Encyclopaedias

Theses

Further reading

External linksWikimedia Commons has media related to 22 October 1917. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||