|

Race to the Sea

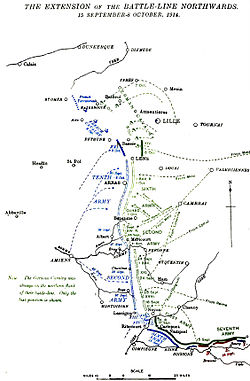

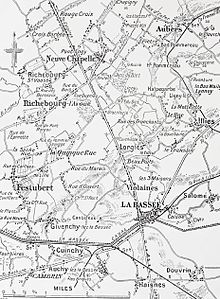

The Race to the Sea (French: Course à la mer; German: Wettlauf zum Meer, Dutch: Race naar de Zee) took place from about 17 September – 19 October 1914 during the First World War, after the Battle of the Frontiers (7 August – 13 September) and the German advance into France. The invasion had been stopped at the First Battle of the Marne (5–12 September) and was followed by the First Battle of the Aisne (13–28 September), a Franco-British counter-offensive.[a] The term describes reciprocal attempts by the Franco-British and German armies to envelop the northern flank of the opposing army through the provinces of Picardy, Artois and Flanders, rather than an attempt to advance northwards to the sea. The "race" ended on the North Sea coast of Belgium around 19 October, when the last open area from Diksmuide to the North Sea was occupied by Belgian troops who had retreated after the Siege of Antwerp (28 September – 10 October). The outflanking attempts had resulted in a number of encounter battles but neither side was able to gain a decisive victory.[b] After the opposing forces had reached the North Sea, both tried to conduct offensives leading to the mutually costly and indecisive Battle of the Yser from 16 October to 2 November and the First Battle of Ypres from 19 October to 22 November. After mid-November, local operations were carried out by both sides and preparations were made to take the offensive in the spring of 1915. Erich von Falkenhayn, Chief of the German General Staff (Oberste Heeresleitung OHL) since 14 September, concluded that a decisive victory could not be achieved on the Western Front and that it was equally unlikely in the east. Falkenhayn abandoned Vernichtungsstrategie (strategy of annihilation) and attempted to create the conditions for peace with one of Germany's enemies, by Ermattungsstrategie (strategy of exhaustion), to enable Germany to concentrate its resources decisively to defeat the remaining opponents. Over the winter lull, the French army established the theoretical basis of offensive trench warfare, originating many of the methods which became standard for the rest of the war. Infiltration tactics, in which dispersed formations of infantry were followed by nettoyeurs de tranchée (trench cleaners), to capture by-passed strong points were promulgated. Artillery observation from aircraft and creeping barrages, were first used systematically in the Second Battle of Artois from 9 May to 18 June 1915. Falkenhayn issued memoranda on 7 and 25 January 1915, to govern defensive battle on the Western Front, in which the existing front line was to be fortified and to be held indefinitely with small numbers of troops, to enable more divisions to be sent to the Eastern Front. New defences were to be built behind the front line to contain a breakthrough until the position was restored by counter-attacks. The Westheer began the huge task of building field fortifications, which were not complete until the autumn of 1915. BackgroundStrategic developmentsPlan XVIIUnder Plan XVII the French peacetime army was to form five field armies, with groups of Reserve divisions attached and a group of reserve divisions was to assemble on each flank, c. 2,000,000 men. The armies were to concentrate opposite the German frontier around Épinal, Nancy and Verdun–Charleville-Mezières, with an army in reserve around Sainte-Menehould and Commercy. Since 1871 railway building had given the French General Staff sixteen lines to the German frontier against thirteen available to the German army and the French could wait until German intentions were clear. The French deployment was intended to be ready for a German offensive in Lorraine or through Belgium. It was anticipated that the Germans would use reserve troops but also expected that a large German army would be mobilised on the border with Russia, leaving the western army with sufficient troops only to advance through Belgium south of the Meuse and the Sambre rivers. French intelligence had obtained a map exercise of the German general staff of 1905, in which German troops had gone no further north than Namur and assumed that plans to besiege Belgian forts were a defensive measure against the Belgian army.[9] A German attack from south-eastern Belgium towards Mézières and a possible offensive from Lorraine towards Verdun, Nancy and St. Dié was anticipated; the plan was an evolution from Plan XVI and made more provision for the possibility of a German offensive through Belgium. The First, Second and Third Armies were to concentrate between Épinal and Verdun opposite Alsace and Lorraine, the Fifth Army was to assemble from Montmédy to Sedan and Mézières and the Fourth Army was to be held back west of Verdun, ready to move east to attack the southern flank of a German invasion through Belgium or southwards against the northern flank of an attack through Lorraine. No formal provision was made for combined operations with the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) but joint arrangements had been made and in 1911 during the Second Moroccan Crisis the French had been told that six divisions could be expected to operate around Maubeuge.[10] Schlieffen–Moltke PlanGerman strategy had given priority to offensive operations against France and a defensive posture against Russia since 1891. German planning was determined by numerical inferiority, the speed of mobilisation and concentration and the effect of the vast increase of the power of modern weapons. Frontal attacks were expected to be costly and protracted, leading to limited success, particularly after the French and Russians modernised their fortifications on the frontiers with Germany. Alfred von Schlieffen, Chief of the Imperial German General Staff, Oberste Heeresleitung (OHL) from 1891–1906, devised plans to evade the French frontier fortifications with an offensive on the flank, which would have a local numerical superiority and obtain rapidly a decisive victory. By 1906, such a manoeuvre was intended to pass through neutral Belgium and threaten Paris from the north.[11] Helmuth von Moltke the Younger succeeded Schlieffen in 1906 and was less certain that the French would conform to German assumptions. Moltke adapted the deployment and concentration plan, to accommodate an attack in the centre or an enveloping attack from both flanks as variants to the plan, by adding divisions to the left flank opposite the French frontier, from the c. 1,700,000 men expected to be mobilised in the Westheer (western army). The main German force would still advance through Belgium and attack southwards into France, the French armies would be enveloped on the left and pressed back over the Meuse, Aisne, Somme, Oise, Marne and Seine, unable to withdraw into central France. Either the French would be annihilated or the manoeuvre from the north would create conditions for victory in the centre or in Lorraine on the common border.[12] Battle of the Frontiers, 7 August – 13 September France, Germany, Luxembourg and Belgium, 1914 (expandable) The Battle of the Frontiers is a general name for all of the operations of the French armies until the Battle of the Marne.[13] A series of encounter battles began between the German, French and Belgian armies, on the German-French frontier and in southern Belgium on 4 August 1914. The Battle of Mulhouse (Battle of Alsace 7–10 August) was the first French offensive against Germany. The French captured Mulhouse until forced out by a German counter-attack on 11 August and fell back toward Belfort. The main French offensive, the Battle of Lorraine (14–25 August), began with the Battles of Morhange and Sarrebourg (14–20 August) advances by the First Army on Sarrebourg and the Second Army towards Morhange. Château-Salins near Morhange was captured on 17 August and Sarrebourg the next day. The German 6th Army and 7th Army counter-attacked on 20 August and the Second Army was forced back from Morhange and the First Army was repulsed at Sarrebourg. The German armies crossed the border and advanced on Nancy but were stopped to the east of the city.[14] To the south the French retook Mulhouse on 19 August and then withdrew. On 24 August, at the Battle of the Mortagne (14–25 August), a limited German offensive in the Vosges, the Germans managed a small advance, before a French counter-attack retook the ground. By 20 August, a German counter-offensive in Lorraine had begun and the German 4th Army and 5th Army advanced through the Ardennes on 19 August towards Neufchâteau. An offensive by French Third and Fourth Armies through the Ardennes began on 20 August, in support of the French invasion of Lorraine. The opposing armies met in thick fog and the French mistook the German troops for screening forces. On 22 August, the Battle of the Ardennes (21–28 August) began with French attacks, which were costly to both sides and forced the French into a disorderly retreat late on 23 August. The Third Army recoiled towards Verdun, pursued by the 5th Army and the Fourth Army retreated to Sedan and Stenay. Mulhouse was recaptured again by German forces and the Battle of the Meuse (26–28 August), caused a temporary halt of the German advance.[15]  Battle of the Frontiers, 1914 (expandable) Liège was occupied by the Germans on 7 August, the first units of the BEF landed in France and French troops crossed the German frontier. On 12 August, the Battle of Haelen was fought by German and Belgian cavalry and infantry and was a Belgian defensive success. The BEF completed its move of four divisions and a cavalry division to France on 16 August, as the last Belgian fort of the Fortified Position of Liège surrendered. The Belgian government withdrew from Brussels on 18 August and the German army attacked the Belgian field army at the Battle of the Gete. Next day the Belgian army began to retire towards Antwerp, which left the route to Namur open; Longwy and Namur were besieged on 20 August. Further west the Fifth Army had concentrated on the Sambre by 20 August, facing north either side of Charleroi and east towards the Belgian Fortified Position of Namur. On the left, the Cavalry Corps (General André Sordet) linked with the BEF at Mons.[14] The Fifth Army was confronted by the German 3rd Army and 2nd Army from the east and the north. Before the Fifth Army could attack over the Sambre the 2nd Army attacked at the Battle of Charleroi and at Namur on 21 August. The 3rd Army crossed the Meuse and attacked the French right flank and on 23 August, the Fifth Army began a retirement southwards to avoid encirclement. After the Battle of St. Quentin, the French withdrawal continued. On 22 August, the BEF advanced and on 23 August fought the Battle of Mons, a delaying action against the German 1st Army, to protect the left flank of the French Fifth Army. The BEF was forced to retreat when the 1st Army began to overrun the British defences on the right flank and the Fifth Army retired from the area south of the Sambre, exposing the British right flank to envelopment. Namur capitulated on 25 August and a Belgian sortie from Antwerp led to the Battle of Malines (25–27 August).[15] After the French defeat during the Battle of Lorraine, the French Second Army retreated to the Grand Couronné heights near Nancy and dug in, on an arc from Pont-à-Mousson to Champenoux, Lunéville and Dombasle-sur-Meurthe by 3 September. The Battle of Grand Couronné (4–13 September) began next day, when the German 7th and 6th Armies attacked simultaneously at St. Dié and Nancy, as the Second Army sent reinforcements to the Third Army. Costly fighting continued until 12 September but the French were able to withdraw more than four corps to reinforce the armies on the left flank.[16] On 13 September, Pont-à-Mousson and Lunéville were recaptured by the French and the advance continued close to the Seille river, where the front stabilised. The battles kept a large number of German troops in Lorraine, as the Great Retreat further west culminated on the Marne.[17] The Great Retreat, 24 August – 5 September German and Allied positions, 23 August – 5 September 1914 The French Fifth Army fell back about 6.2 mi (10 km) from the Sambre during the Battle of Charleroi (22 August) and began a greater withdrawal from the area south of the Sambre on 23 August. The BEF fought the Battle of Mons on 24 August, by when the French First and Second armies had been pushed back by attacks of the German 7th and 6th armies between St. Dié and Nancy, the Third Army held positions east of Verdun against attacks by the 5th Army, the Fourth Army held positions from the junction with the Third Army south of Montmédy, westwards to Sedan, Mezières and Fumay, facing the 4th Army and the Fifth Army was between Fumay and Maubeuge, with the 3rd Army advancing up the Meuse valley from Dinant and Givet into a gap between the Fourth and Fifth Armies and the 2nd Army pressed forward into the angle between the Meuse and Sambre directly against the Fifth Army. On the far west flank of the French, the BEF prolonged the line from Maubeuge to Valenciennes against the 1st Army and Army Detachment von Beseler masked the Belgian Army at Antwerp.[18] On 26 August, German forces captured Valenciennes and conducted the Siege of Maubeuge (24 August – 7 September). Leuven (Louvain) was sacked by German troops and the Battle of Le Cateau was fought by the BEF and the 1st Army. Longwy was surrendered by its garrison and next day, British Royal Marines and a party of the Royal Naval Air Service (RNAS) landed at Ostend; Lille and Mezières were occupied by German troops. Arras was occupied on 27 August and a French counter-offensive began at the Battle of St. Quentin (also known as the Battle of Guise 29–30 August). On 29 August the Fifth Army counter-attacked the 2nd Army south of the Oise, from Vervins to Mont Dorigny and west of the river from Mont Dorigny to Moy towards St. Quentin on the Somme, while the British held the line of the Oise west of La Fère.[19] Laon, La Fère and Roye were captured by German troops on 30 August and Amiens the next day. On 1 September, Craonne and Soissons were captured and on 5 September the BEF ended its retreat from Mons, German troops reached Claye, 6.2 mi (10 km) from Paris, Reims was captured, German forces withdrew from Lille and the First Battle of the Marne (Battle of the Ourcq) (5–12 September) began, marking the end of the Great Retreat of the western flank of the Franco-British armies.[20] By 4 September, the First and Second Armies had slowed the advance of the 7th and 6th armies west of St. Dié and east of Nancy, from where the Second Army had withdrawn its left flank, to face north between Nancy and Toul. A gap between the left of the Second Army and the right of the Third Army at Verdun, which faced north-west, on a line towards Revigny against the 5th Army advance, west of the Meuse between Varennes and St. Ménéhould. The Fourth Army had withdrawn to Sermaize, west to the Marne at Vitry-le-François and then across the river to Sompons, against the 4th Army, which had advanced from Rethel, to Suippes and the west of Châlons. The new Ninth Army held a line from Mailly against the 3rd Army, which had advanced from Mézières, over the Vesle and the Marne west of Châlons. The 2nd Army had advanced from Marle on the Serre, across the Aisne and the Vesle, between Reims and Fismes to Montmort, north of the junction of the Ninth and Fifth Armies at Sézanne. The Fifth Army and the BEF had withdrawn south of the Oise, Serre, Aisne and Ourq, pursued by the 2nd Army on a line from Guise to Laon, Vailly and Dormans and by the 1st Army from Montdidier, towards Compiègne and then south-east towards Montmirail. The new French Sixth Army, linked with the left of the BEF, west of the Marne at Meaux, to Pontoise north of Paris. French garrisons were besieged at Strasbourg, Metz, Thionville, Longwy, Montmédy and Maubeuge. The Belgian army was invested at Antwerp in the National Redoubt and at Liège, fortress troops continued the defence of the forts.[21] Eastern Front Eastern Front, 1914 Austria-Hungary had declared war on Serbia on 28 July and on 1 August, military operations began on the Polish border. Libau was bombarded by a German cruiser on 2 August and on 5 August Montenegro declared war on Austria-Hungary. On 6 August, Austria-Hungary declared war on Russia and Serbia declared war on Germany; war began between Montenegro and Germany on 8 August. The Battle of Stallupönen (17 August) caused a minor check to the Russian invasion of East Prussia and on 12 August, Britain and France declared war on Austria-Hungary, as Austrian forces crossed the Save and seized Shabatz. Next day, Austrian forces crossed the Drina and began the first invasion of Serbia. The Battle of Cer (Battle of the Jadar, 17–21 August) began and the Battle of Gumbinnen in East Prussia took place from 19–20 August.[22] On 21 August, Austro-Hungarian forces withdrew from Serbia. The Battle of Tannenberg (26–30 August) began in East Prussia and in the Battle of Galicia (23 August – 11 September) the First Battle of Kraśnik was fought in Poland from 23–25 August. Shabatz was retaken by Serbian forces and the last Austrian troops retired across the Drina, ending the First Austrian Invasion of Serbia. The First Battle of Lemberg (26–30 August) began in Galicia and the Battle of Komarów (26 August – 2 September) and the Battle of Gnila Lipa (26–30 August) began in Poland. A naval action took place off Åland and a German cruiser SMS Magdeburg ran aground and was intercepted by a Russian squadron.[22]  Silesia, 1914 On 3 September, Lemberg was captured by the Russian army and the Battle of Rawa (Battle of Tarnavka 7–9 September) began in Galicia. The First Battle of the Masurian Lakes (7–14 September) began and on 8 September, the Austro-Hungarian army commenced the Second Invasion of Serbia, leading to the Battle of Drina (6 September – 4 October). The Second Battle of Lemberg (8–11 September) began and on 11 September, Austrian forces in Galicia retreated. The Battle of the Masurian Lakes ended on 15 September and Czernowitz in Bukovina was taken by the Russian army. On 17 September, Serbian forces in Syrmia were withdrawn and Semlin evacuated, as the Battle of the Drina ended. Next day General Paul von Hindenburg was appointed Oberbefehlshaber der gesamten Deutschen Streitkräfte im Osten (Ober Ost, Commander-in-Chief of German Armies in the Eastern Theatre).[23] On 21 September, Jaroslaw in Galicia was taken by the Russian army. On 24 September, Przemyśl was isolated by Russian forces, beginning the First Siege as Russian forces conducted the First Invasion of North Hungary (24 September – 8 October). Military operations began on the Niemen (25–29 September) but German attacks were suspended on 29 September. The retreat of Austro-Hungarian forces in Galicia ended and Maramaros-Sziget was captured by the Russian army; an Austro-Hungarian counter-offensive began on 4 October and Maramaros-Sziget was retaken. On 9 October, the First German Offensive against Warsaw began with the battles of Warsaw (9–19 October) and Ivangorod (9–20 October).[24] As the situation on the eastern front deteriorated in September, the new German high command under General Falkenhayn attempted to retrieve the situation in France and inflict a decisive defeat.[23] Tactical developmentsOperations in Belgium, August–October 1914 German invasion of Belgium, August 1914 On 2 August 1914, the Belgian government refused the passage of German troops through Belgium to France and on the night of 3/4 August, the Belgian General Staff ordered the Third Division to Liège to obstruct a German advance. Covered by the Third Division, the Liège fortress garrison, a screen of the Cavalry Division and detachments from Liège and Namur, the rest of the Belgian field army closed up to the river Gete by 4 August, covering central and western Belgium and the communications towards Antwerp. The German invasion began on 4 August, when an advanced force of six German brigades from the 1st, 2nd and 3rd Armies, crossed the German-Belgian border. Belgian resistance and German fear of Francs-tireurs, led the Germans to implement a policy of Schrecklichkeit (frightfulness) against Belgian civilians soon after the invasion, in which massacres, executions, hostage taking and the burning of towns and villages took place and became known as the Rape of Belgium.[25] On 5 August, the advanced German forces tried to capture Liège and the forts of the Fortified Position of Liège by coup de main. The city fell on 6 August but the forts were not captured and on 12 August, five German super-heavy 420 mm (17 in) howitzers and four batteries of Austrian 305 mm (12.0 in) howitzers, began systematically to bombard the Belgian defences, until the last fort fell on 16 August.[26] On 18 August, the Germans began to advance along the Meuse River towards Namur and the Belgian field army began a withdrawal from its positions along the Gete, to the National Redoubt at Antwerp. On 20 August, the German 1st Army took Brussels unopposed and the Belgian field army reached Antwerp, with little interference from German advanced parties, except for an engagement between the 1st Division and the German IX Corps near Tienen, in which the Belgians had 1,630 casualties.[27] While the BEF and the French armies conducted the Great Retreat into France (24 August – 28 September), small detachments of the Belgian, French and British armies conducted operations in Belgium against German cavalry and Jäger.[28] On 27 August, a squadron of the RNAS had flown to Ostend, for air reconnaissance sorties between Bruges, Ghent and Ypres.[29] British marines landed at Dunkirk on the night of 19/20 September and on 28 September occupied Lille. The rest of the brigade occupied Cassel on 30 September and scouted the country in motor cars. An RNAS Armoured Car Section was created, by fitting vehicles with bullet-proof steel.[30][31] On 2 October, the Marine Brigade was moved to Antwerp, followed by the rest of the Naval Division on 6 October, having landed at Dunkirk on the night of 4/5 October. From 6–7 October, the 7th Division and the 3rd Cavalry Division landed at Zeebrugge.[32] Naval forces collected at Dover were formed into a separate unit, which became the Dover Patrol, to operate in the Channel and off the French-Belgian coast.[33]  Fortified Region of Antwerp Antwerp was invested to the south and east by German forces after 20 August, while the main German armies chased the French and British over the border southwards to the Marne. Belgian forces in Antwerp tried to assist the French and British with sorties on 24–26 August, 9–13 September and 26–27 September. On 28 September, German heavy and super-heavy artillery began to bombard Belgian fortifications around Antwerp.[34] On 1 October, the Germans attacked forts Sint-Katelijne-Waver and Walem and the Bosbeek and Dorpveld redoubts, held by the 5th Reserve and Marine divisions. By 11:00 a.m., Fort Walem was severely damaged and Fort Lier was hit by 16 in (410 mm) shells but Fort Koningshooikt, the Tallabert and Bosbeek redoubts were mostly intact; the intervening ground between Fort Sint-Katelijne-Waver and Dorpveld redoubt had been captured. Despite reinforcement by the Royal Naval Division from 2 October, the Germans penetrated the outer ring of forts. When the German advance began to compress a corridor from the west of the city along the Dutch border to the coast, the Belgian field army withdrew from Antwerp westwards towards the coast. On 9 October, the remaining garrison surrendered and the Germans occupied the city. Some British and Belgian troops escaped to the Netherlands, where they were interned for the duration of the war. The Belgian withdrawal was protected by a French Marine brigade, Belgian cavalry and the British 7th Division around Ghent. On 15 October, the Belgian army occupied a defensive line along the Yser river in west Flanders, from Diksmuide to the coast.[35] First Battle of the Marne, 5–12 September Battle of the Marne, 1914 Joffre used the railways which had transported French troops to the German frontier to move troops back from Lorraine and Alsace to form a new Sixth Army under General Michel-Joseph Maunoury with nine divisions and two cavalry divisions. By 10 September, twenty divisions and three cavalry divisions had been moved west from the German border to the French centre and left and the balance of force between the German 1st, 2nd and 3rd armies and the Third, Fourth, Ninth, Fifth armies, the BEF and Sixth Army had changed to 44:56 divisions. Late on 4 September, Joffre ordered the Sixth Army to attack eastwards over the Ourcq towards Château Thierry as the BEF advanced towards Montmirail and the Fifth Army attacked northwards, with its right flank protected by the Ninth Army along the St. Gond marshes. The French First, Second, Third and Fourth armies to the east, were to resist the attacks of the German 5th, 6th and 7th armies between Verdun and Toul and repulse an enveloping attack on the defences south of Nancy from the north. The 6th and 7th armies were reinforced by heavy artillery from Metz and attacked again on 4 September along the Moselle.[36] On 5 September, the Sixth Army advanced eastwards from Paris and met the German IV Reserve Corps, which had moved into the area that morning and stopped the French advance short of high ground north of Meaux. Overnight, the IV Reserve Corps withdrew to a better position 6.2 mi (10 km) east and French air reconnaissance observed German forces moving north to face the Sixth Army. General Alexander von Kluck the 1st Army commander, ordered the II Corps to move back to the north bank of the Marne, which began a redeployment of all four 1st Army corps to the north bank by 8 September. The swift move to the north bank prevented the Sixth Army from crossing the Ourcq but created a gap between the 1st and 2nd armies. The BEF advanced from 6–8 September, crossed the Petit Morin, captured bridges over the Marne and established a bridgehead 5.0 mi (8 km) deep. The Fifth Army also advanced into the gap and by 8 September, had crossed the Petit Morin, which forced Bülow to withdraw the right flank of the 2nd Army. Next day the Fifth Army re-crossed the Marne and the German 1st and 2nd armies began to retire as the French Ninth, Fourth and Third Armies fought defensive battles against the 3rd Army which then had to retreat with the 1st and 2nd armies on 9 September.[37] Further east, the Third Army was forced back to the west of Verdun as German attacks were made on the Meuse Heights to the south-east but managed to maintain contact with Verdun and the Fourth Army to the west. German attacks against the Second Army south of Verdun from 5 September, almost forced the French to retreat but on 8 September, the crisis eased. By 10 September, the German armies west of Verdun were retreating towards the Aisne and the Franco-British were following-up, collecting stragglers and equipment. On 12 September, Joffre ordered an outflanking move to the west and an attack northwards by the Third Army, to cut off the German retreat. The pursuit was too slow and by 14 September, the German armies had dug in north of the Aisne and the Allies met trench lines, rather than rearguards. Frontal attacks by the Ninth, Fifth and Sixth armies were repulsed from 15–16 September, which led Joffre to begin the transfer of the Second Army west to the left flank of the Sixth Army, the first phase of the operations to outflank the German armies, which from 17 September to 17–19 October, moved the opposing armies through Picardy and Flanders, to the North Sea coast.[38] First Battle of the Aisne, 13–28 September Opposing positions: 5 September (dashed red line) 13 September (solid red line) On 10 September, the French armies and the BEF advanced to exploit the victory of the Marne and the armies on the left flank advanced, opposed only by rearguards. On 11 and 12 September, Joffre ordered outflanking manoeuvres but the advance was too slow to catch the Germans, who on 14 September, began to dig in on high ground on the north bank of the Aisne, which reduced the French advance from 15–16 September to a few local gains. French troops had begun to move westwards on 2 September, over undamaged railways which could move a corps to the left flank in from 5–6 days. On 17 September, the French Sixth Army attacked from Soissons to Noyon, with the XIII and IV corps, supported by the 61st and 62nd divisions of the 6th Group of Reserve Divisions, after which the fighting moved north to Lassigny and the French dug in around Nampcel.[39] The French Second Army arrived from the eastern flank and took over command of the left-hand corps of the Sixth Army, as indications appeared that German troops were also being moved from the eastern flank.[40] The German IX Reserve Corps arrived from Belgium by 15 September and next day attacked with the 1st Army to the south-west with the IV Corps and the 4th and 7th cavalry divisions, against the attempted French envelopment. The attack was cancelled and the corps withdrew behind the right flank of the 1st Army. The 2nd and 9th cavalry divisions were sent next day but the French attack reached Carlepont and Noyon, before being contained on 18 September. In the Battle of Flirey, the German armies attacked from Verdun west to Reims and the Aisne on 20 September, cut the main railway from Verdun to Paris and created the St Mihiel salient. The main German effort remained on the western flank, which the French discovered by intercepting wireless messages.[41] By 28 September, the Aisne front had stabilised and the BEF began to withdraw on the night of 1/2 October, with the first troops arriving in the Abbeville area on 8/9 October.[42] PreludeGerman planAfter the defeat on the Marne, Moltke ordered a retirement to the Aisne by the 1st and 2nd armies on the German right wing and a withdrawal to Reims and a line eastwards past the north of Verdun, by the 3rd, 4th and 5th armies. The 6th and 7th armies were ordered to end their attacks and dig in.[43] The withdrawal was intended to make time for the 7th Army to be transferred from Alsace to the right-wing near the Oise but Franco-British attacks led to the 7th Army being sent to fill the gap between the 1st and 2nd armies instead. Moltke was replaced by Falkenhayn on 14 September, by when the 1st Army had reached the Aisne, with its right flank on the Oise and the 7th Army had assembled on the Aisne, between the 1st and 2nd armies. Further east the 3rd, 4th and 5th armies had dug in from Prosnes to Verdun, secure from frontal attacks. The 1st Army was still vulnerable on its northern flank, to attacks by French troops transferred from the south, which could be moved faster over undamaged railways, than German troops using lines damaged during the Great Retreat.[23] General Wilhelm Groener, head of the Railway Department of the OHL, suggested three alternatives, a frontal attack from the new positions, a defence of the line of the Aisne while reserves were transferred to the right flank or to continue the withdrawal and comprehensively regroup the German armies, ready to conduct an offensive on the right flank.[44] On 15 September, Falkenhayn wanted to continue the withdrawal and ordered the 1st Army to fall back and dig in from Artems to La Fère and Nouvion-et-Catillon, to protect the right flank from a French offensive, while the 6th Army moved from Lorraine to the western flank, ready for a general offensive to begin progressively on 18 September from the 5th Army in the east, pinning French troops down westwards, until the 6th Army enveloped the French, beyond the right of the 1st Army. The plan was cancelled soon afterwards, when Oberst (Colonel) Gerhard Tappen (OHL Operations Branch), reported from a tour of inspection at the front that the French were too exhausted to begin an offensive, that a final push would be decisive and that more withdrawals would compromise the morale of the German troops, after the defeat on the Marne.[44] From 15–19 September Falkenhayn ordered the 1st, 2nd and 7th armies, temporarily under the command of General Karl von Bülow, to attack southwards and the 3rd, 4th and 5th armies to attack with the intention of weakening the French and preventing troops from being moved westwards. The 6th Army began to move to the western flank on 17 September, ready for a decisive battle (Schlachtentscheidung) but French attacks on 18 September, led Falkenhayn to order the 6th Army to operate defensively to secure the German flank.[7] French plan of attackFrench attempts to advance after the German retirement to the Aisne were frustrated after 14 September, when German troops were discovered to have stopped their retirement and dug in on the north bank of the Aisne. Joffre ordered attacks on the German 1st and 2nd armies but attempts by the Fifth, Ninth and Sixth armies to advance from 15 to 16 September had little success. The Deuxième Bureau (French Military Intelligence) also reported German troop movements from east to west, which led Joffre to continue the transfer of French troops from the east, which had begun on 2 September with the IV Corps and continued on 9 September with the XX Corps, 11 September with the XIII Corps and the XIV Corps on 18 September. The depletion of the French forces in the east, took place just before the Battle of Flirey, a German attack on 20 September against the Third Army on either side of Verdun, the Fifth Army north of Reims and the Sixth Army along the Aisne, which ended with the creation of the St. Mihiel Salient. Joffre maintained the French emphasis on the western flank, after receiving intercepted wireless messages, showing that the Germans were moving an army to the western flank and continued to assemble the Second Army to the north of the Sixth Army. On 24 September the Second Army was attacked and found difficulty in holding ground, rather than advancing around the German flank as intended.[45] BattleFirst phase, 25 September – 4 OctoberBattle of Picardy, 22–26 September Initial moves, Franco-German Race to the Sea, 1914 The French Sixth Army began to advance along the Oise, west of Compiègne on 17 September. French reconnaissance aircraft were grounded during bad weather and cavalry were exhausted, which deprived the French commanders of information. As news reached Joffre that two German corps were moving south from Antwerp, the Sixth Army was forced to end its advance and dig in around Nampcel and Roye. The IV and XIII corps were transferred to the Second Army, along with the 1st, 5th, 8th and 10th Cavalry divisions of the Cavalry Corps (General Louis Conneau), the XIV and XX Corps were withdrawn from the First and the original Second Army to assemble south of Amiens, with a screen of the 81st, 82nd, 84th and 88th Territorial divisions, to protect French communications. The French advanced on 22 September, on a line from Lassigny northwards to Roye and Chaulnes around the German flank but met the German II Corps, which had arrived on the night of 18/19 September, on the right flank of the IX Reserve Corps.[46] Despite the four divisions of the II Cavalry Corps (General Georg von der Marwitz), the Germans were pushed back to a line from Ribécourt to Lassigny and Roye, which menaced German communications through Ham and St. Quentin. On 24 September, the French were attacked by the XVIII Corps as it arrived from Reims, which forced back the French IV Corps at Roye on the right flank. To the north, the French reached Péronne and formed a bridgehead on the east bank of the Somme, only for the German XIV Reserve Corps to reach Bapaume to the north on 26 September. The offensive capacity of the Second Army was exhausted and defensive positions were occupied, while Joffre sent four more corps to reinforce. Over the next week, the northern flank of the Second Army moved further north and on 29 September, a subdivision d'armée (General Louis de Maud'huy) was formed, to control the northern corps of the Second Army as they assembled near Arras.[47] Battle of Albert, 25–29 SeptemberOn 21 September, Falkenhayn decided to concentrate the 6th Army near Amiens, to attack westwards to the coast and then envelop the French northern flank south of the Somme. The offensive by the French Second Army forced Falkenhayn to divert the XXI and I Bavarian Corps as soon as they arrived, to extend the front northwards from Chaulnes to Péronne on 24 September and drive the French back over the Somme. On 26 September, the French Second Army dug in on a line from Lassigny to Roye and Bray-sur-Somme; German cavalry moved north to enable the II Bavarian Corps to occupy the ground north of the Somme. On 27 September, the German II Cavalry Corps drove back the 61st and 62nd Reserve divisions (General Joseph Brugère, who had replaced General Albert d'Amade), to clear the front for the XIV Reserve Corps and link with the right flank of the II Bavarian Corps. The French subdivision d'armée began to assemble at Arras and Maud'huy found that instead of making another attempt to get around the German flank, the subdivision was menaced by a German offensive.[48] The German II Bavarian and XIV Reserve corps pushed back a French Territorial division from Bapaume and advanced towards Bray-sur-Somme and Albert.[48] From 25–27 September, the French XXI and X Corps north of the Somme, with support on the right flank by the 81st, 82nd, 84th and 88th Territorial divisions and the 1st, 3rd, 5th and 10th Cavalry divisions of the French II Cavalry Corps, defended the approaches to Albert. On 28 September, the French were able to stop the German advance on a line from Maricourt to Fricourt and Thiepval. The German II Cavalry Corps was stopped near Arras by the French cavalry. On 29 September, Joffre added X Corps, 12 mi (20 km) north of Amiens, to the French II Cavalry Corps south-east of Arras and a provisional corps (General Victor d'Urbal), which had a Reserve division in Arras and one in Lens, to a new Tenth Army.[49] Second phase, 4–15 OctoberFirst Battle of Arras, 1–4 October Attacks on Arras, October 1914 On 1 October, the French at Arras were pushed back from Guémappe, Wancourt and Monchy-le-Preux, until the arrival of X Corps.[50] By 1 October, two more French corps, three infantry and two cavalry divisions had been sent northwards to Amiens, Arras, Lens and Lille, which increased the Second Army to eight corps, along a front of 62 mi (100 km). Joffre ordered Castelnau to operate defensively, while Maud'huy and the subdivision d'armée advanced on Arras. On 28 September, Falkenhayn had ordered the 6th Army to conduct an offensive by the IV, Guard and I Bavarian corps near Arras and more offensives further north.[51][c] Rupprecht intended to halt the French west of Arras and envelop them around the north side of the city.[51] On 1 October, the French attacked to the south-east, expecting only a cavalry screen.[53] The Germans attacked from Arras to Douai on 1 October, forestalling the French. On 3 October, Rupprecht reinforced the 6th Army north of Arras and ordered the IV Cavalry Corps from Valenciennes to Lille. From 3 to 4 October, German attacks on Arras and the vicinity were costly failures. On 4 October, German troops entered Lens, Souchez, Neuville-Saint-Vaast and gained a footing on the Lorette Spur. German attacks were made from the north of Arras to reach the Scarpe but were eventually repulsed by X Corps.[50] By 4 October, German troops had also reached Givenchy-en-Gohelle and on the right flank of the French further south, the Territorial divisions were separated from X Corps, prompting Castelnau and Maud'huy to recommend a retreat. Joffre made Maud'huy's subdivision d'armée independent as the Tenth Army and told Castelnau to keep the Second Army in position because the increasing number of troops arriving further north would divert German pressure.[54] By 6 October, the Second Army front from the Oise to the Somme and the Tenth Army front from Thiepval to Arras and Souchez had been stabilised.[55] A German cavalry attack to the north of the 6th Army, pushed back the French Territorial divisions from Lens to Lille and on 5 October, Marwitz ordered the cavalry to advance westwards to Abbeville on the Channel coast and cut the railways leading south. At the end of 6 October, Falkenhayn terminated attempts by the 2nd Army to break through in Picardy. To the north, I Cavalry Corps and II Cavalry Corps attacked between Lens and Lille, quickly being forced back behind the Lorette Spur. The next day, the cavalry was attacked by the first troops of the French XXI Corps to arrive as they advanced eastwards from Béthune.[55] Third phase, 15 October–NovemberBattle of La Bassée, 10 October – 2 November La Bassée area, 1914 The German 6th Army took Lille before a British force could secure the town and the 4th Army attacked the exposed British flank at Ypres. On 9 October, the German XIV Corps arrived opposite the French and the German 1st and 2nd Cavalry corps tried a flanking move between La Bassée and Armentières but the French cavalry stopped the Germans north of La Bassée Canal. The German 4th Cavalry Corps passed through Ypres on 7 October and was forced back to Bailleul by French Territorial troops.[56] From 8–9 October the British II Corps arrived by rail at Abbeville and advanced on Béthune. By the end of 11 October, II Corps held a line from Béthune to Hinges and Chocques, with flanking units on the right, 2.2 mi (3.5 km) south of Béthune and on the left 2.8 mi (4.5 km) to the west.[57] On 12 October, II Corps attacked to reach Givenchy and Pont du Hem, 3.7 mi (6 km) north of La Bassée Canal. The German I and II Cavalry corps and attached Jäger tried to delay the advance but the British repulsed a counter-attack near Givenchy.[58] From 14 to 15 October, II Corps attacked eastwards up La Bassée Canal and managed short advances on the flanks, with help from French cavalry but lost 967 casualties. From 16–18 October the corps attacks pivoted on the right and the left flank advanced to Aubers against German opposition at every ditch and bridge. A foothold was established on Aubers Ridge on 17 October and French cavalry captured Fromelles. On 18 October, the German XIII Corps arrived, reinforced the VII Corps and gradually forced the British II Corps to a halt. On 19 October, parties of British infantry and French cavalry captured the village of Le Pilly, which later was recaptured by the Germans. The fresh German 13th and 14th divisions arrived and counter-attacked the II Corps front. By 21 October, II Corps was ordered to dig in from the canal near Givenchy to Violaines, Illies, Herlies and Riez, while offensive operations continued to the north. The Lahore Division of the Indian Corps arrived and the British repulsed German attacks until early November, when both sides concentrated their resources on the First Battle of Ypres and the battle at La Bassée ended.[59] Battle of Messines, 12 October – 2 November Messines area, 1914 The III Corps reached St. Omer and Hazebrouck from 10–12 October, then advanced eastwards towards Lille. The British cavalry advanced and found the Germans dug in on Mont des Cats and at Flêtre on the road from Cassel to Bailleul. The 3rd Cavalry Brigade attacked Mont des Cats and occupied Mt. Noir, 1.9 mi (3 km) north of Bailleul. On 14 October, the cavalry advanced north-eastwards, occupied Dranoutre and Kemmel against slight opposition, then reached a line from Dranoutre to Wytschaete (Wijtschate), linking with the 3rd Cavalry Division of IV Corps, which had been operating in Belgium since early October.[60] On 15 October, Estaires was captured by French cavalry but the Germans prevented an advance beyond Comines, 3.4 mi (5.5 km) west of Menin (Menen), where German troops had arrived during the night. A foothold was gained at Warneton and German outposts west of the Ypres–Comines canal were pushed back to the far side. By 16 October, the Cavalry Corps and the 3rd Cavalry Division held the Lys river from Armentières to Comines and the Comines canal to Ypres. The BEF was ordered to make a general advance on 16 October, as the German forces were falling back. The cavalry was ordered to cross the Lys between Armentières and Menin as the III Corps advanced north-east to gain touch with the 7th Division near Ypres.[61] Fog grounded Royal Flying Corps (RFC) reconnaissance aircraft and made artillery observation impossible. The Lys was 45–60 ft (14–18 m) wide and 5 ft (1.5 m) deep and flanked by water meadows.[61] The banks were cut by boggy streams and dykes, which kept the cavalry on the roads; German outposts were pushed back but dismounted cavalry attacks could not dislodge the German defenders and the cavalry in Warneton town were withdrawn during the night. The attack was resumed on 18 October, when the cavalry attacked from Deûlémont to Tenbrielen but made no progress against a strong and well-organised German defence, ending the day opposite Deûlémont in the south to the railway at Tenbrielen to the north. From 9–18 October, the Cavalry Corps had c. 175 casualties. The encounter battle ended and subsequent operations in the Battle of Messines took place after the end of the "Race to the Sea".[62] Battle of Armentières, 13 October – 2 November Locations of the Allied and German armies, 19 October 1914 On 11 October, the British III Corps comprising the 4th and 6th divisions arrived by rail at St. Omer and Hazebrouck and then advanced behind the left flank of II Corps, towards Bailleul and Armentières.[63] II Corps was to advance around the north of Lille and III Corps was to reach a line from Armentières to Wytschaete, with the Cavalry Corps (Lieutenant-General Edmund Allenby, 1st Viscount Allenby) on the left as far as Ypres. French troops were to relieve the II Corps at Béthune to move north and link with the right of III Corps but this did not occur. On the northern flank of III Corps, in front of the Cavalry Corps, was a line of hills from Mont des Cats to Mt. Kemmel, about 400 ft (120 m) above sea level, with spurs running south across the British line of advance, occupied by the German IV Cavalry Corps with three divisions. On 12 October, the British cavalry advanced and captured the Mont des Cats.[60] On 13 October, III Corps found German troops dug in along the Meterenbecque. A corps attack from La Couronne to Fontaine Houck began at 2:00 p.m. in wet and misty weather and by evening had captured Outtersteene and Méteren, at a cost of 708 casualties. On the right, French cavalry attempted to support the attack but without howitzers, could not advance in level terrain, dotted with cottages used as improvised strong points. The German defenders slipped away from defences in front of houses, hedges and walls, well sighted to keep the soldiers invisible, dug earth having been scattered rather than used for a parapet, which would have been visible. III Corps was to attack the next German line of defence before German reinforcements could reach the scene. Rain and mist made air reconnaissance impossible on 14 October but patrols found that the Germans had fallen back beyond Bailleul and crossed the Lys.[64] Allied forces completed a continuous line to the North Sea when British cavalry and infantry reached a line from Steenwerck–Dranoutre, after a slow advance against German rearguards, in poor visibility and close country. III Corps closed up to the river at Sailly, Bac St. Maur, Erquinghem and Pont de Nieppe, linking with the cavalry at Romarin. On 16 October, the British secured the Lys crossings and late in the afternoon, German attacks began at Diksmuide and the next day the III Corps occupied Armentières. On 18 October, the III Corps was ordered to join an offensive by the BEF and the French army, by attacking down the Lys valley. Part of Pérenchies ridge was captured but much stronger German defences were encountered and the infantry were ordered to dig in.[64] On the night of 18/19 October, the III Corps held a line from Radinghem to Pont Rouge, west of Lille. The encounter battle ended and subsequent operations in the Battle of Armentières took place after the end of the Race to the Sea during the First Battle of Ypres (19 October – 22 November).[62] AftermathAnalysis German and Allied operations, Artois and Flanders, September–November 1914 From 17 September to 17 October, the belligerents had made unsuccessful reciprocal attempts to turn the northern flank of their opponent. A German offensive began by 21 October but the 4th and 6th armies were only able to take small amounts of ground at great cost to both sides, at the Battle of the Yser (16–31 October) and further south at Ypres. Falkenhayn then attempted to achieve a limited goal of capturing Ypres and Mount Kemmel, in the First Battle of Ypres (19 October – 22 November).[65] By 8 November, Falkenhayn concluded that the attempt to advance along the coast had failed and that taking Ypres was impossible.[66] The French and Germans had not been able to assemble forces near the northern flank fast enough to obtain a decisive advantage. Where the opposing forces had attempted to advance, they had quickly been stopped and forced to improvise field defences, against which attacks were costly failures. By the end of the First Battle of Ypres both sides were exhausted, short of ammunition and suffering from collapses in morale and refusals of orders by some infantry units.[67] In October 1914, French and British artillery commanders met to discuss means for supporting infantry attacks, the British practice being to keep the artillery silent until targets were identified and the French firing a rafale (preliminary bombardment) which ceased as the infantry began the assault. A moving barrage of fire was proposed as a combination of both methods and became a standard practice later in the war as guns and ammunition were accumulated in sufficient quantity.[68] Falkenhayn issued memoranda on 7 and 25 January 1915, defining a theory of defensive warfare to be used on the Western Front, intended to enable ground to be held with the fewest possible troops. By economising on manpower in the west, a larger number of divisions could be sent to the Eastern Front.[69] The front line was to be fortified to enable its defence with small numbers of troops indefinitely and the captured ground was to be recovered by counter-attacks. A second trench was to be dug behind the front line, to shelter the trench garrison and to have easy access to the front line, through covered communication trenches. Should counter-attacks fail to recover the front trench, a rearward line was to be connected to the remaining parts of the front line, limiting the loss of ground to a bend (Ausbeulung) in the line, rather than a breakthrough. The building of the new defences took until the autumn of 1915 and confronted Franco-British offensives with an evolving system of field fortifications, which was able to absorb the increasing power and sophistication of breakthrough attempts.[69]

During the mobile operations of 1914, armies operating in hostile territory had relied on wireless communication to a far greater extent than anticipated, having expected to use telegraphs, telephones and dispatch riders. None of the armies had established cryptographic systems sufficient to prevent eavesdropping and all of the armies sent messages containing vital information in plain language. From September–November, the British and French intercepted c. 50 German messages, which showed the disorganisation of the German command in mid-September and the gap between the 1st and 2nd armies on the eve of the Battle of the Marne. Similar plain language messages and the reading of crudely coded German messages, gave warnings to the British of the times, places and strengths of eight attacks by four German corps or more, during the Race to the Sea and the battles in Flanders.[71] CasualtiesBy the end of the battles at Ypres, German army casualties in the west were 800,000 men, including 116,000 dead.[72] The French army casualty total from October–November was 125,000 men, which, with losses of 329,000 men from August–September, gave a total of 454,000 casualties by the end of the year.[73] In 2001, Strachan recorded 80,000 German casualties at Ypres, 89,964 British casualties since the beginning of the war, (54,105 incurred at Ypres) and that c. 50 per cent of the Belgian army had become casualties.[74] Subsequent operationsFirst Battle of FlandersBattle of the Yser, 18 October – 30 November Map of Yser area, 1914 During the Allied retreat from Antwerp, the British IV Corps moved north of Ypres on 14 October, where I Corps arrived on 19 October, with cavalry covering a gap to the south of the town. The Battle of the Yser (18 October – 30 November 1914) was fought, along a 22 mi (35 km) stretch of the Yser river and Yperlee Canal in Belgium. Falkenhayn created a new 4th Army to capture Dunkirk and Calais to inflict an "annihilating blow".[75] The retreat of the Belgians to the Yser ended the "Race to the Sea", with the Belgians holding a 9.3 mi (15 km) front southwards from the coast and Belgian, French and British troops holding another 9.3 mi (15 km) beyond, the BEF holding 25 mi (40 km) and the Tenth Army holding another 16 mi (25 km) on the extreme right flank of the northern front.[35] German attacks began on 18 October and on 22 October German troops gained a foothold over the river at Tervaete. The French 42nd Division at Nieuwpoort was sent as reinforcements on 23 October, when the Belgians were pushed back between Diksmuide and Nieuwpoort. German heavy artillery was countered on the coast by Allied ships under British command, which forced Germans to attack further inland.[76] On 24 October, fifteen German attacks crossed the Yser for 3.1 mi (5 km) and the French sent the rest of the 42nd Division. By 26 October, the Belgian Commander General Félix Wielemans, had decided to retreat but French objections and orders from King Albert led to a withdrawal being cancelled. The next day, the Belgians opened sluice gates on the coast at Nieuwpoort, flooding the area between the Yser and the railway embankment. On 30 October, a German attack crossed the embankment at Ramscapelle but was repulsed on the following evening; the inundations reduced the fighting to local operations.[77] First Battle of Ypres, 19 October – 22 November Opposing forces at Ypres, October 1914 The First Battle of Ypres (part of the First Battle of Flanders) began on 19 October, with attacks by the German 6th and 4th armies, as the BEF attacked towards Menin and Roeselare (Roulers). On 21 October, the 4th Army was repulsed in mutually costly fighting and from 23–24 October, the Germans attacked on the Yser with the 4th Army and with the 6th Army to the south. French attacks by a new Eighth Army were made towards Roeselare and Torhout (Thourout), which diverted German troops from British and Belgian positions. A new German attack was planned where the 4th and 6th armies would pin down Allied troops and armeegruppe von Fabeck with six new divisions and more than 250 heavy guns, attacked north-west between Messines and Gheluvelt, against the British I Corps. The Germans took ground on the Menin road on 29 October and drove back the British cavalry next day, to a line 1.9 mi (3 km) from Ypres. Three French battalions were sent south and on 31 October, a British battalion counter-attacked and drove back the German troops from the Gheluvelt crossroads.[78] By 1 November, the BEF was close to exhaustion and the French XIV Corps was moved north from the Tenth Army and the French IX Corps attacked southwards towards Becelaere, which relieved the pressure on the British flanks. German attacks began to diminish on 3 November, by when armeegruppe von Fabeck had lost 17,250 casualties. A French offensive was planned for 6 November towards Langemarck (Langemark) and Messines but was forestalled by German attacks from 5–8 November and 10–11 November. The main attack on 10 November was made by the 4th Army between Langemarck and Diksmuide, in which Diksmuide was lost by the Franco-Belgian garrison. Next day, the British were subjected to an unprecedented bombardment between Messines and Polygon Wood and then attacked by the Prussian Guard, which broke into British positions along the Menin road, before being forced back by counter-attacks.[79] From mid-October to early November, the German 4th Army lost 52,000 and the 6th Army lost 28,000 casualties.[80] Notes

Footnotes

References

Further reading

External links

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||