|

A Short Walk in the Hindu Kush

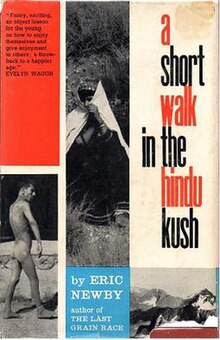

A Short Walk in the Hindu Kush is a 1958 book by the English travel writer Eric Newby. It is an autobiographical account of his adventures in the Hindu Kush, around the Nuristan mountains of Afghanistan, ostensibly to make the first mountaineering ascent of Mir Samir. Critics have found it comic, intensely English, and understated. It has sold over 500,000 copies in paperback.[1] The action in the book moves from Newby's life in the fashion business in London to Afghanistan. On the way Newby describes his very brief training in mountaineering in North Wales, a stop in Istanbul, and a nearly-disastrous drive across Turkey and Persia. They are driven out to the Panjshir Valley, where they begin their walk, with many small hardships described in a humorous narrative, supported by genuine history of Nuristan and brief descriptions of the rare moments of beauty along the way. Disagreements with Newby's Persian-speaking companion Hugh Carless, and odd phrases in an antique grammar book, are exploited to comic effect. The book has been reprinted many times, in at least 16 English versions and in Spanish, Chinese and German editions. While some critics, and Newby himself, have considered Newby's Love and War in the Apennines a better book, A Short Walk was the book that made him well-known, and critics agree that it is very funny in an old-school British way. BackgroundIn 1956 at the age of 36, Eric Newby ended his London career in fashion[2] and decided impulsively to travel to a remote corner of Afghanistan where no Englishman had ventured for 60 years.[3] He sent a telegraph to his friend the diplomat Hugh Carless, then due to take up his position as First Secretary in Tehran later that year, requesting he accompany him on an expedition to Northern Afghanistan.[4] They were poorly prepared and inexperienced, but Newby and Carless vowed to attempt Mir Samir, a glacial and then unclimbed[5] 20,000 foot peak in the Hindu Kush.[6] The bookPublicationA Short Walk was first published in 1958 by Secker & Warburg. It has been reprinted many times since in both Britain and the USA. The book has been translated into French (1989), Spanish (1997), Chinese (1998), German (2005), Swedish (2008) and Croatian (2016).[7][8] Illustrations and maps The book was illustrated with monochrome photographs taken by Newby or Carless.[9] There are two hand-drawn maps. The "Map to illustrate a journey in Nuristan by Eric Newby and Hugh Carless in 1956", shows an area of 75 × 55 miles covering the Panjshir valley to the Northwest, and Nuristan and the Pushal valley to the Southeast; it has a small inset of Central Asia showing the area's location to the Northeast of Kabul. The other map, "Nuristan", covers a larger area of about 185 × 140 miles, showing Kabul and Jalalabad to the South, and Chitral and the Pakistan region of Kohistan to the East.[10] PrefaceA two-page preface by the novelist Evelyn Waugh recommends the book, remarking on its "idiomatic, uncalculated manner", and that the "beguiling narrative" is "intensely English". He hopes that Newby is not the last of a "whimsical tradition". He explains that Newby is not the other English writer of the same name and confesses (or pretends) that he began to read it thinking that it was the other man's work. He sketches out the "deliciously funny" account of Newby selling women's clothes, and the "call of the wild" (he admits it is an absurdly trite phrase) that led him to the Hindu Kush. Waugh ends by advising the "dear reader" to "fall to and enjoy this characteristic artifact."[11] StructureThe book is narrated in the first person by Newby. Newby begins with an anecdotal description of his frustration with life in the fashion business in London, and how he came to leave it. He tells how he and his friend Carless receive brief training in mountaineering technique, on boulders and small cliffs in North Wales. The inn's waitresses are expert climbers; they take Newby and Carless up a difficult climbing route, Ivy Sepulchre[a] on Dinas Cromlech. Newby drives to Istanbul with his wife, Wanda. Meeting Carless, they drive across Turkey to Persia (present day Iran). They brake to an emergency stop on the road, just short of a dying nomad, and with difficulty convince the police they did not cause the death. Wanda returns home and the men cross Persia and Afghanistan, driving 5,000 miles (8,000 km) in a month, through Herat to Kandahar and Kabul. There are comic touches, as when "The proprietor Abdul, a broken-toothed demon of a man, conceived a violent passion for Hugh."[13] Newby and Carless try to acclimatise to the altitude with a practice walk. They visit the Foreign Ministry, hire an Afghan cook, and buy a "very short" list of supplies. Newby describes the geography of Nuristan "walled in on every side by the most formidable mountains" and a little history, with the legend of descent from Alexander the Great, the British imperial adventures, and pre-war German expeditions.[14] They are driven out from Kabul to the Panjshir valley by a servant from the Embassy. They stay in a tall mud house in a place with mulberry trees, vines and willows by a river. Hugh puts the dinner guests to sleep with a complicated story "about an anaconda killing a horse".[15]  Newby and Carless take on three "very small" horses and their horse-drivers. The cook has to return to Kabul. Despite having horses, they decide to carry 40 pound (20 kg) packs "to toughen ourselves up".[16] Walking in the heat causes the local people to insult them, and makes their drivers angry, which does not make negotiating their pay any easier. Trying to find their feet, they push themselves hard, and get upset stomachs and blisters. They find a man "with his skull smashed to pulp"; the head driver suggests they should leave the place immediately. Two lammergeiers, carrion feeders, circle overhead.[17] Newby describes how he and Carless become tired of each other's company, and of the food they have brought. They come to a ruinous summer pasture village, and eat local food: boiled milk, the yellow crust that forms on cream, and fresh bread. They catch sight of their goal, Mir Samir in the Hindu Kush mountains. They find tracks of ibex and wolf. A local guide catches a snowcock by running after it. Newby and Carless arrive at the West wall of the mountain, wondering what they have let themselves in for. They walk up the glacier wearing new crampons, probing for crevasses with their ice-axes. They cross the bergschrund and climb a little on rock. Carless suggests abseiling 200 feet (60 m) to the next glacier, a place where they would have been trapped. Wisely, they return to their base camp and try again the next morning, again finding their way blocked. They wish the climbing waitresses from Wales were with them.  They find an injured boy dressed in a goatskin to draw the poison from his wounds. Newby has to eat the tail of a fat-tailed sheep. They are escorted up the Chamar valley by a greedy albino. Newby tries to learn a little of the Bashguli language from a 1901 Indian Staff Corps grammar, which contains an absurd selection of phrases; the book exploits some of these to comic effect.[18] The next day they attempt to climb the East ridge in hot weather. The rock is gritty with sharp flakes of mica. They pretend to be Damon Runyon characters to cheer themselves up.[19] They get better at roped climbing and reach 18,000 feet before returning for the night, assuring themselves they could succeed if they start earlier and try a different route. They pass a bitterly cold night below a cliff where rocks continually fall; there is a thunderstorm. They eat pea soup, tinned apple pudding, and jam straight from the tin, and try to sleep. The next day they try to ascend a 70 degree ice slope, reaching the ridge after five hours, not the two they had estimated. At 19,100 feet they have a tremendous view of the Hindu Kush, the Anjuman Pass, Tirich Mir, and the mountains that border Pakistan. Choughs croak above them. They are only 700 feet below the summit, but four hours away, so once again they turn back,[20] They return to camp at 9 p.m. after climbing for 17 hours. Carless makes an impressive speech in Persian to convince the drivers to continue into Nuristan. They climb an indistinct track to the pass. They descend into Nuristan: it grows hot. Men run to meet them: they are told they are the first Europeans ever to cross the pass – Newby does not believe this – and are given ice-cold milk to drink. They make camp in a loop of the river to reduce the risk of being murdered in the night. They are visited by two evil-looking men with an ancient Martini–Henry rifle, riding a horse. In the morning they try out the Bashguli grammar on a man; he understands, but speaks a different dialect. Their guide does not let them camp in a grove of mulberry trees full of girls and young women, but chooses a dirty place under a cliff. They undress to wash in the river, discovering how thin they have become.[21] An audience gathers to watch them get up and cook. They reach Pushal,[22] where the headman gives them apricots and tells tales of the old days. They admire the antique rifles of many kinds that the men have.[23] A mullah forbids them to go to a funeral where a bullock is to be slaughtered, in a holiday atmosphere. Instead, they sit under a walnut tree beside a river, with kingfishers, butterflies, hummingbird hawkmoths, and a woodpecker drilling.[24] Newby shakes hands with two lepers. They all have dysentery. Newby negotiates the price of a complete male Nuristani costume.  Walking down from the village of Lustagam they pass hand-made irrigation canals of hollowed-out halved tree trunks on stone pillars. They are shown a rock, the Sang Neveshteh, with an inscription in Kufic script, supposedly recording the Emperor Timur Leng's visit in 1398 A.D.[25] The country becomes lusher, with both ordinary mulberries and the king mulberry, plums, sloes and soft apples. They cross a wooded country with watermills, wild raspberries and buttercups.[26] They climb back through rougher country to Gadval, a village on a cliff, with picturesque privies over the streams. At Lake Mundul a mullah swims the horse with Newby's camera and all their film and other possessions across the river. The headman shows a scar inflicted on him in deep snow by a black bear. Newby and Carless climb 2,000 feet out of the valley to reach Arayu village. At Warna they rest by a waterfall with mulberry trees. They walk on, Newby dreaming of cool drinks and hot baths. They struggle on over a high cold pass. The last village of Nuristan, Achagaur, is peopled by Rajputs who claim to come from Arabia. They reach the top of the Arayu pass[27] and cheerfully descend on the far side. They meet the explorer and author of Arabian Sands, Wilfred Thesiger, who is disgusted by their air-beds and calls them "a couple of pansies".[28][29] ReceptionCritics such as the travel writer Alexander Frater have noted that while the book is held in extremely high esteem,[b] and is enjoyably comic,[30][31] it is not nearly as well-written as his later autobiographical book, Love and War in the Apennines (1971), a judgement in which Newby concurred.[29][32][33][34] The travel writer John Pilkington stated that the book had been an early inspiration in his life, and wrote of Newby that "He had an understated, self-deprecating sense of humour which was very British – perfect travel writing."[35] Michael Shapiro, interviewing Newby for Travelers' Tales, called the book "a classic piece of old-school British exploration, and established Newby's trademark self-deprecating wry humor"[36] and included it in WorldHum's list of favourite travel books.[37] Boyd Tonkin, writing in The Independent, called the book a "classic trek", and commented that while it is told light-heartedly, Newby, despite his comic gift, always retained his "capacity for wonderment".[38]  Kari Herbert noted in The Guardian's list of travel writer's favourite travel books that she had inherited a "well-loved copy" of the book from her father, the English polar explorer Wally Herbert. "Like Newby, I was in a soulless job, desperate for change and adventure. Reading A Short Walk was a revelation. The superbly crafted, eccentric and evocative story of his Afghan travels was like a call to arms."[34] Outside magazine includes A Short Walk among its "25 essential books for the well-read explorer",[39] while Salon.com has the book in its list of "top 10 travel books of the [20th] century".[40] The Daily Telegraph too enjoyed the English humour of the book, including it in a list of favourite travel books, and describing Newby and Carless's meeting with the explorer Wilfred Thesiger as a "hilarious segment". It quotes "We started to blow up our air-beds. 'God, you must be a couple of pansies,' said Thesiger."[41] The Swedish journalist and travel writer Tomas Löfström noted that the meeting with Thesiger represented, in Newby's exaggerated account, a collision between two generations of travel writers who travelled, wrote, and related to strangers quite differently.[42] Margalit Fox, writing Newby's obituary in The New York Times, noted that the trip was the one that made him famous, and states that "As in all his work, the narrative was marked by genial self-effacement and overwhelming understatement." She cites a 1959 review in the same publication by William O. Douglas, later a Supreme Court judge, who called the book "a chatty, humorous and perceptive account", adding that "Even the unsanitary hotel accommodations, the infected drinking water, the unpalatable food, the inevitable dysentery are lively, amusing, laughable episodes."[43] The American novelist Rick Skwiot enjoyed the "blithely confident Brit's" narrative style, finding echoes of its concept, structure and humour in Bill Bryson's A Walk in the Woods. Skwiot notes the hazards of the journey as crevasses, precipices, thieves, bears, disease, thirst, hunger. "Somehow they blunder on toward their whimsical destination", he remarks, the "seductive and tickling narrative" told with "understatement, self-effacement, savage wit, honed irony, and unrelenting honesty." The reader is drawn in "by his endearingly flawed humanity."[44] In Varieties of Nostalgia in Contemporary Travel Writing, Patrick Holland and Graham Huggan observed that "travel writing, like travel itself, is generated by nostalgia". But the "anachronistic gentleman" can only exist, they note, quoting Simon Raven, "in circumstances that are manifestly contrived or unreal". The resulting "atmosphere of enhanced affectation is exploited to maximum comic effect" in books such as A Short Walk, which they called "an acclaimed post-Byronic escapade in which gentlemanly theatrics come to assume the proportions of full-blown farce."[45] The essayist and professor of English Samuel Pickering called A Short Walk and Newby's later book Slowly Down the Ganges "vastly entertaining", reminiscent of earlier British travellers such as Robert Byron (The Road to Oxiana, 1937), but also "episodic, each day cluttered with odd occurrences that are striking because they occur in exotic lands". Pickering noted that Newby's combination of whimsy with close observation fitted in to the British travel writing tradition. In his view, Newby's writing has aged, but like old wine, it goes down smoothly, and remains invigorating.[46] LegacyThe Austrian alpinist Adolf Diemberger wrote in a 1966 report that in mountaineering terms Newby and Carless's reconnaissance of the Central Hindu Kush was a "negligible effort", admitting however that they "almost climbed it".[47] The climb was more warmly described in the same year as "The first serious attempt at mountaineering in that country [the Afghan Hindu Kush]" by the Polish mountaineer Boleslaw Chwascinski.[5] In January 2012, an expedition under the auspices of the British Mountaineering Council, citing the "popular adventure book", attempted the first winter ascent of Mir Samir, but it was cut short by an equipment theft and "very deep snow conditions and route finding difficulties".[48] Notes

References

Edition

External links |

||||||||||||||||||||