|

Zungwini Mountain skirmishes

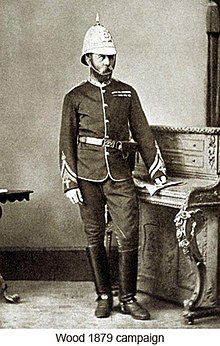

Advance from Utrecht to Tinta's Kraal Patrols to Zungwini Mountain, 20 & 22 January Patrol to the vicinity of Hlobane Mountain, 24 January Withdrawal to Khambula Luneburg is at the upper left of the mapThe Zungwini Mountain skirmishes took place on 20, 22 and 24 January 1879 during the Anglo-Zulu War. The mountain was a stronghold of the AbaQulusi Zulu tribe, who were reinforced by the forces of exiled Swazi prince Mbilini waMswati. The mountain lay near the proposed route of advance of a British column under Lieutenant-Colonel Evelyn Wood, one of three that marched on the Zulu capital, Ulundi, from early January. Aware that the other columns had made less progress Wood, who had halted to fortify a camp at Tinta's Kraal, decided to deal with the abaQulusi strongholds. On 20 January a force of 104 irregular horse under Wood's subordinate, Lieutenant-Colonel Redvers Buller, carried out a reconnaissance of Zungwini Mountain. Buller captured a number of kraals before ascending the mountain where he was attacked by a force of 1,000 Zulu. Buller fought a short defensive action before withdrawing, with the Zulus in pursuit. Buller returned to Wood after making a second stand and driving off his pursuers. The action of 20 January led Wood to order a stronger attack on the mountain, with a force under his command with regular infantry and artillery. Wood reached Zungwini on 22 January and ascended the mountain, driving off a small Zulu force and capturing livestock. The British spotted a force of 4,000 Zulu but Wood decided it was too late in the day to launch an attack. The force rested at Zungwini on 23 January and attacked on 24 January, the artillery inflicting casualties and dispersing a Zulu force before driving back the main body of Zulu. By this point Wood had received news of the defeat of the British centre column at the 22 January Battle of Isandlwana, which exposed his right flank to the main Zulu army. Wood ordered a withdrawal back to Tinta's Kraal and then to Kambula, from which he sent several raids against the abaQulusi before joining the second invasion of Zululand in June, which resulted in British victory in the war. Prelude British forces invaded Zululand in January 1879, during the Anglo-Zulu War. The advance was made in three columns, a left column under Lieutenant-Colonel Evelyn Wood, a centre column under Lieutenant-General Frederic Thesiger, 2nd Baron Chelmsford and a right column under Colonel Charles Pearson. Wood was tasked with advancing into north-western Zululand.[1] He commanded a force of around 2,500 men. His fighting forces included eight companies of regular infantry from the 13th and (Wood's own) 90th Regiments of Foot, six artillery pieces from No 11 Battery, 7th Brigade, Royal Artillery and around 300 black auxiliaries known as Wood's Irregulars. Wood's column also included around 200 mounted white irregulars under Lieutenant-Colonel Redvers Buller.[2] North-western Zululand was the province of the AbaQulusi tribe, descended from a regiment (iButho) established by King Shaka.[3] The king in 1879, Cetshwayo, ordered the abaQulusi, under their senior inDuna Msebe kaMadaka, to oppose any British advance.[1] They were to be reinforced by Swazi prince and exile Mbilini waMswati, who maintained a homestead on the flank of the hill of Hlobane.[1][4] The surrender of Mbilini was one of the terms of the British ultimatum that started the war.[5] The abaQulusi were among the most loyal supporters of Cetshwayo and Wood expected them to put up a fierce opposition to his advance.[6] Wood considered the presence of the abaQulusi, who maintained strongholds on the flat-topped mountains of Zungwini, Hlobane and Ityenka, a threat to his supply lines and left flank and thought their defiance intimidated chiefs who might otherwise have surrendered to the British without bloodshed.[1][3][7][8] Mbilini, who took control of the abaQulusi forces and those of the Kubheka from the Ntombe valley, pursued a defensive strategy, influenced by that of the Swazi people. He evacuated the low-lying homesteads and withdrew his men and cattle to the hilltops.[5] Wood advanced from Utrecht in the Transvaal Republic, via Balte Spruit, and entered Zululand on 7 January. His column reached Bemba's Kop on 13 January and halted there for four days. He advanced 10 miles (16 km) eastwards to the Insegene River on 18 January, where a small skirmish was fought by Wood's Irregulars.[9] On 19 January the column secured the surrender of Zulu chief Tinta, who was sent back to Utrecht, and rested a day at his homestead, which they began to fortify; becoming known as Fort Tinta.[2][9] By this time Buller's irregular horse, scouting ahead of the column, had captured 600 Zulu cattle but found no significant opposition.[10] Wood was aware that the other columns were making slow progress and decided to use the time afforded to him to deal with the abaQulusi strongholds.[7] 20 January

On the morning of 20 January Buller rode out from Fort Tinta with 104 irregular horse, including men of the Frontier Light Horse, to carry out a reconnaissance of Zungwini Mountain.[1][9] Buller's force crossed the White Umfolozi River 2 miles (3.2 km) north of Mount Iseki.[8] He advanced to and captured Mabomba's kraal on the south-eastern spur of Zungwini.[8][1] A party of Boer irregulars, under Piet Uys, found 50 armed Zulu nearby at Seketwayo's Kraal. The Zulu fled into broken ground and were pursued by the Boers and 20 dismounted men sent by Buller. In the resulting skirmish twelve Zulu were killed and one Boer wounded by a thrown assegai. Four Zulu firearms and a number of assegai were recovered.[8] After the skirmish Uys' men reported more Zulu present on the top of the mountain. A force under Buller ascended the slope by a cattle track to gain a view of the surrounding area but the Zulu moved to prevent his ascent.[8] Around 1,000 Zulu advanced on Buller, in their flanking horns of the buffalo formation.[1] Buller's force coalesced on a rocky knoll and fought off the central, chest, of the Zulu formation, inflicting at least eight dead on the Zulu, but were outflanked by the movement of the Zulu left wing, 300-strong, and right wing, 400-strong.[1][8] Buller ordered a withdrawal down the mountain, during which a man of the Frontier Light Horse was wounded and two others struck by spent musket balls. A horse belonging to one of the Boers was also hit.[8] The Zulu pursued Buller as far as the White Umfolozi, with around 100 crossing the river before Buller turned his force round to drive them off. The Zulu force retreated back to the Zungwini.[1][8] The Zulus involved in the skirmish on 20 January included the abaQulusi and some of Mbilini's followers.[11] Buller wrote of the action: "I endeavoured to cross the upper plateau ... but the hill was too strongly held for us to force it". Wood did not hear about the skirmish until 7 pm when he received a note from Buller, sent during the withdrawal. Wood had recently sent 70 empty ox-drawn wagon back to Balte Spruit and was concerned for their safety, as Buller's note had been sent before he had seen off his pursuers.[7] 22 January

Wood completed his fortification of Fort Tinta on 21 January and determined to lead a stronger force to Zungwini.[11][9] Leaving only two companies of regular infantry (one each from the 13th and 90th) to guard the fort he set out at midnight on 21 January.[12][9] The horse were again led by Buller, while Wood led the advance with the 90th Regiment and his Irregulars. The 13th Regiment made up the rearguard.[13] Buller's force, with two artillery pieces, went to the western portion of the Zungwini Mountain range, Wood with the 90th and the Irregulars went to a point 3 miles (4.8 km) east of Buller in the middle of the range and the remaining forces, under Colonel Gilbert of the 13th Regiment, occupied a point to the south-east of the mountain.[9] Wood and Buller's parties converge on the summit of Zungwini at around 6 am, having met no resistance. They proceeded to the eastern slopes where they encountered and drove off a Zulu force, capturing a large quantity of livestock.[9][11] The Zulu withdrew across the Zungweni/Ityenka Nek towards Hlobane and Wood and Buller, following them, then saw a force of around 4,000 Zulu drilling on the north-western slopes of that mountain.[14][12][15] This force was mainly abaQulusi under their chieftain Msebe (who lived at Hlobane), but also a significant number of Mbilini's men.[13][16] Wood judged it too late in the day to launch an attack and he ordered his men to descend the mountain to bivouac with Gilbert's force.[9][12] After dark the men heard cannon fire from the direction of the centre column's camp at Isandlwana which Wood thought indicated an "unfavourable situation".[15] The camp had been overrun in the Battle of Isandlwana earlier that afternoon, so this sound came from a portion of the column that had been away on a reconnaissance with Chelmsford and returned to the camp that evening.[13] 24 January

With his men having been active in the field for 20 hours on 22 January Wood ordered a day of rest on 23 January, the force remaining at Gilbert's position close to Zungwini.[13][9] In the early morning of the following day Wood advanced with a strong force that included the four of the 7-pounder artillery pieces under Brevet Lieutenant-Colonel E. G. Tremlett.[1][17][15] The force had advanced 8 miles (13 km) by 7.30 am reaching a point between the Zungwini and Ntendeka mountains when they encountered a party of abaQulusi Zulus running towards them.[12][11] They also came under fire from Zulu hidden in rocks on the slopes of Zungwini Mountain. Wood moved to his right to launch an attack with the 13th Regiment, the Boer irregulars and two guns leaving the 90th Light Infantry, two guns and baggage to follow. He recalled that he and Uys had to ride ahead of the men to encourage them on.[15] The artillery pieces unlimbered and opened fire, killing 50 Zulu and dispersing the remainder, who withdrew up Hlobane mountain.[12][14][11] A cattle track to Wood's front proved to be impassable for the artillery so Wood passed around a rise on his left flank to continue the advance.[12] He came across the 90th Regiment advancing against a force of 4,000 Zulu, but having left their ammunition carts guarded only by a party of unarmed buglers who were being threatened by a force of 200 Zulu.[15] It was at this point that a messenger reached Wood, carrying news of the British defeat at Isandlwana. The man had been sent by Captain Alan Coulston Gardner, one of the few British officers to survive the battle. Gardner had escaped to Helpmekaar, Natal, but realised that Wood, whose force was just 35 miles (56 km) from Isandlwana, was vulnerable to attack by the victorious Zulu. Gardner found no volunteer willing to carry a message so rode from Helpmekaar to Utrecht where he found a rider to carry the news to Wood.[12] Gardner's note explained that Chelmsford had ridden out from the camp at Isandlwana with much of the centre column, and in his absence the camp had been attacked and overrun with the loss of two artillery pieces and almost all of the men.[15] Wood sent a message to Buller, who was with the horsemen, notifying him of the disaster and ordering his men to drive back the 200 Zulu. In the meantime Wood remonstrated with the commander of the 90th Regiment for advancing without orders. The regiment fired around two volleys before the Zulu force withdrew ahead of them. Wood ordered a pursuit, led by the Frontier Light Horse and Boers. After two hours Wood halted the men and gave them news of the defeat at Isandlwana.[15] Wood realised that the defeat meant his right flank was exposed and he could not capitalise on his successes at Zungwini.[18] He ordered the force to withdraw back to Fort Tinta.[1][2][15] Wood and Buller's victories at Zungwini had undermined local support for the abaQulusi and the war against the British; the eclipse of 22 January had also been held by the Zulu as a portent of the decline in Mbilini's power. The Zulu victory at Isandlwana countered this and persuaded the local Zulu chiefs to rally to the Zulu king.[18] Later eventsWood and his men reached Fort Tinta on 25 January.[9] He considered the position too exposed and lacking in firewood to serve as a long-term base. Having no desire to return to Bemba's Kop or Balte Spruit in the south-west he decided to strike out westwards to Kambula.[19] Wood's men loaded up the stores left at Fort Tinta and abandoned the post on 26 January. They reached the White Umfolozi on 27 January and arrived at Khambula on 31 January, which they fortified.[20] On 28 January Wood had received orders from Chelmsford, advising him that he "must now be prepared to have the whole of the Zulu Army on [his] hands any day". Expecting an attack on his post Wood later recalled not sleeping for more than 2–3 hours at a time over the next three months, as he insisted on checking on the sentries personally.[21] On 1 February Wood razed an abaQulusi stronghold east of Hlobane, killing six Zulu, burning 250 huts and taking 270 cattle.[21] Wood's forces continued to make such harassing attacks on the Zulu but he was embarrassed by a Zulu raid on the Transvaal settlement of Lüneburg on 10–11 February.[18] Wood afterwards sent Buller on retaliatory raids in the Intombe valley where his irregular horse were highly successful, killing 34 Zulu and recovering 375 oxen and 254 goats that the Zulu had taken from Lüneburg; British losses amounted to two of Wood's Irregulars killed.[22][23] On 12 March a British supply convoy and its escort, bound for Lüneburg, were lost in the Battle of Intombe. Again Wood responded with further retaliatory raids.[22] Wood was approached by Hamu, a defecting Zulu chief, and agreed to send a force to the far side of Hlobane to escort Hamu's people into British-held territory. On 14 March Wood and Buller left with a force of 360 men, including some of Hamu's warriors. They reached Hamu's territory by nightfall and the following day headed back with 958 refugees, largely women and children. The camped near Zungwini on 15 March and reached Kambula on the following day.[24] Wood became convinced that the abaQulusi and Mbilini's forces needed to be pushed out of their mountain strongholds before Chelmsford's second invasion could begin.[4] Wood lead a raid on Hlobane on 28 March that resulted in defeat as the British were cut off on the mountain top by the abaQulusi and elements of Cetshwayo's army.[14] After the survivors of Wood's force were pursued as far as Zungwini.[25] The following day the Zulu made an unsuccessful attack on Kambula.[26] The attempt cost the Zulu 2,000 dead and 1,000 seriously wounded; Wood pursued the survivors to Zungwini.[27] Chelmford's second invasion began on 31 May and Wood was assigned command of a flying column. His first action, on 5 June, was an inconclusive skirmish at Zungeni mountain. Following a steady and careful advance into Zululand the Zulu were defeated at the 4 July Battle of Ulundi and the war brought to a close.[28][29] References

Bibliography

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||