|

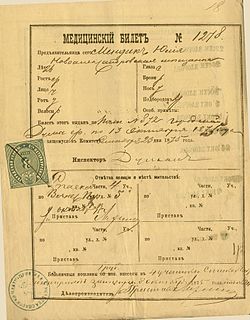

Yellow ticket  Yellow ticket, yellow passport or yellow card[1] (Russian: жёлтый билет[2]) was an informal name of a personal identification document of a prostitute in the Russian Empire between 1843 and 1909. The document combined an ID card, a residence permit, a license to practice prostitution, and prostitute's medical check-up card. The official title of the document varied: medical card (медицинский билет), replacement card (заменительный билет), etc. The title "replacement card" refers to the fact that upon registration, the prostitute left her original passport or residence permit (вид на жительство) in the local police office and was issued the "yellow card" as a replacement personal ID. The carriers of the card were subject to periodic medical check-ups. This requirement was dropped in 1909.[1] Zhyolty bilet ("yellow card") and zheltobiletnitsa ("yellow-card-holder") have become euphemisms for prostitution and prostitutes in Russian language. A traditional etymology is that the document was named so for its yellow color. Another alleged association of yellow color with prostitution is that Tsar Paul (“Pavel”) I, known for his obsession with uniforms, ordered that prostitutes wear yellow dresses to differentiate them from other women in public settings.[1] Jewish women"Yellow ticket" was of additional significance for Jewish women, beyond prostitution. The yellow ticket as a residence permit allowed the holders to live beyond the Pale of Settlement, and according to contemporary witnesses thousands of young Jewish women took upon themselves the stigma of being labelled a prostitute and the burden of biweekly medical check-ups without actually being prostitutes, for the purpose of escaping the Pale and seeking higher education in Moscow and Saint-Petersburg.[3][4] This situation was used in plots of a number of Jewish dramas in the early 20th century[4] and notably in the 1914 Broadway play The Yellow Ticket by Michael Morton (which was the base of The Yellow Passport and The Yellow Ticket, US feature movies). Pola Negri, a Polish actress who later became a Hollywood star, acted in two silent film versions of the story (Poland 1915 and Germany 1918). A restored version of the latter toured the United States in 2013 accompanied by a newly commissioned score for the latter by the klezmer violinist Alicia Svigals. References

|