|

Yampa River

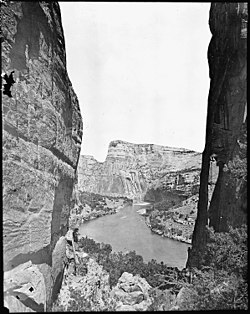

The Yampa River flows 250 miles (400 km) through northwestern Colorado, United States. Rising in the Rocky Mountains, it is a tributary of the Green River and a major part of the Colorado River system. The Yampa is one of the few free-flowing rivers in the western United States, with only a few small dams and diversions. The name is derived from the Snake Indians word for the Perideridia plant, which has an edible root. John C. Frémont was among the first to record the name 'Yampah' in entries of his journal from 1843, as he found the plant was particularly abundant in the watershed. CourseThe headwaters of the Yampa are in the Park Range in Routt County, Colorado as the confluence of the Bear River and Phillips Creek, near the town of Yampa. The Bear River, larger of the two, flows from a source of 11,600-foot (3,500 m) at Derby Peak in the Flat Tops Wilderness. The Yampa River then flows north through a high mountain valley, through Stagecoach Reservoir and Lake Catamount, before reaching Steamboat Springs, where it turns sharply west. Below Steamboat Springs, the Yampa flows through a wider valley in the western foothills of the Rockies. It receives the Elk River from the north, then passes the towns of Milner and Hayden.[5] After entering Moffat County the Yampa passes Craig and is joined by the Williams Fork. West of Craig, the Yampa crosses arid, sparsely populated sagebrush country for about 50 miles (80 km) before reaching Cross Mountain Canyon, where the river slices a 1,000 ft (300 m) deep gap through the namesake mountain. Below Cross Mountain the Yampa enters the open valley of Lily Park, where it is joined by its largest tributary, the Little Snake River. Further west it enters Dinosaur National Monument, where it traverses more than 40 miles (64 km) of rugged canyons and rapids. The Yampa joins the Green in Echo Park at Steamboat Rock deep within the national monument, about 5 miles (8.0 km) from the Colorado–Utah border.[5] WatershedThe Yampa drains 7,660 square miles (19,800 km2) of mostly semi-arid plateau country in northwestern Colorado and a small portion of southern Wyoming. The bulk of the watershed is located between the Park Range, to the east; the Flat Tops, to the south; and the Uinta Mountains, to the west. The Great Divide Basin, an area of closed drainage, borders the Yampa River basin to the north. The Continental Divide runs along the north and east sides of the Yampa basin, separating it from the headwaters of the North Platte River, which flows into the Mississippi River system. On the south, the Yampa River basin is bordered by that of the White River, which like the Yampa flows in a westerly direction to join the Green. Volume The Yampa River is a typical Western snow-fed stream, but unlike most other rivers in the western United States its seasonal discharge patterns are not affected by large dams and water projects. The river forms a noticeably wide, shallow braided stream throughout much of its course. The lower three fourths of the Yampa, from the Elk River down, are navigable by small craft. However the meandering, shallow nature of the river can render the river unnavigable during late summer in low water years. The average flow at the confluence of the Green is 2,154 cubic feet per second (61 m3/s), averaging 5,400 cu ft/s (153 m3/s) during the spring runoff of April–July, and falling below 500 cu ft/s (14 m3/s) during late summer and autumn. The upper section of the river freezes over between December and March.[6] According to a U.S. Geological Survey stream gage at Deerlodge Park, about 50 miles (80 km) above the mouth, the average river flow was 2,082 cu ft/s (59.0 m3/s) between 1983 and 2013. The highest annual mean was 4,431 cu ft/s (125.5 m3/s) in 2011, and the lowest 678 cu ft/s (19.2 m3/s) in 2002. Monthly recorded average flows were highest in May at 8,200 cu ft/s (230 m3/s) and lowest in September at 342 cu ft/s (9.7 m3/s). The highest recorded peak flow was 33,200 cu ft/s (940 m3/s) during the record snowmelt of May 18, 1984.[4] EcologyBecause the Yampa River maintains a relatively natural flow pattern, it supports a productive riparian zone environment along much of its course. In addition, much of the river is unconstrained by levees allowing it to maintain its natural floodplain. This is also true of its main tributary, the Little Snake River. The Yampa River Preserve 17 miles (27 km) west of Steamboat Springs protects a rare riparian forest type consisting of narrowleaf cottonwood, box elder and red-osier dogwood that was once more common in the Upper Colorado River Basin.[7] The Yampa's warm, silty waters are an ideal spawning ground for native fish such as the Colorado pikeminnow and humpback chub which have largely disappeared from dammed waterways in other parts of the Colorado River system.[6] History Native AmericansArchaeological studies conducted in the Dinosaur National Monument have revealed evidence of human habitation up to 7000 BC.[8] The Fremont culture or Desert Archaic people inhabited the Yampa River basin starting about 800 AD, but disappeared for reasons uncertain during the 1400s.[8] The Fremont created petroglyphs along the Yampa River Canyon, of which more than 300 are still visible today.[9] After the collapse of the Fremont culture, a branch of the Utes moved into the Yampa River basin. The White River Utes inhabited the valleys of the Yampa and White Rivers and the Rockies of northwestern Colorado. The band living in the Yampa River valley was known as the Yamparika or Yapudttka Utes.[10] At times the river also served as a boundary between the Utes and Shoshone peoples to the north; there was also a band of Shoshone called the Yamparika.[11] The name Yamparika is a Snake Indians word meaning "yampa eaters", "yampa" referring to the edible roots of the Perideridia plant. "Yampa" itself probably meant "water-plant" or "common plant".[12] In 1843 explorer John C. Frémont was among the first to record the name "Yampah", finding this plant to be of particular abundance in the watershed. Some fur traders in the 1800s thought Yampa was the Ute word for "bear", and the Yampa was often called the Bear River on early maps.[13][14] Dam and diversion proposalsDuring the 1960s, the Yampa and Green River canyons were slated to be flooded under a reservoir created by Echo Park Dam, a U.S. Bureau of Reclamation water project. Due to environmentalists' opposition, this dam was never built, and the free-flowing character of the Yampa was retained. However, as part of the compromise to preserve Echo Park, the controversial Glen Canyon and Flaming Gorge dam projects were allowed to move forward, damming the Colorado and Green Rivers, respectively. Today the Yampa remains the only major tributary in the Colorado River system without a single large dam along its course (the moderately sized Stagecoach Dam, built 1989 and several others on the headwaters have only a limited impact on its flow). In December, 2006, a report proposed to pump water from the Yampa River 200 miles east, under the Continental Divide, to the state's major cities along the Front Range. The diversion was proposed to start near Maybell, 20 miles (32 km) downstream of Craig, Colorado .[15][16] The proposal faces widespread opposition because it could lower river flows in late summer due to the diversion. [citation needed] See alsoReferences

External linksWikimedia Commons has media related to Yampa River. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||