|

William Pūnohu White

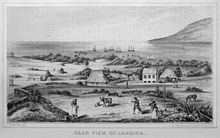

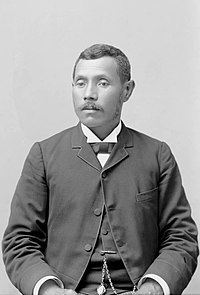

William Pūnohuʻāweoweoʻulaokalani White (Hawaiian pronunciation: [puːnohuˌʔaːweoaːweoˌʔuləokəˈlɐni]; August 6, 1851 – November 2, 1925) was a Hawaiian lawyer, sheriff, politician, and newspaper editor. He became a political statesman and orator during the final years of the Kingdom of Hawaii and the beginnings of the Territory of Hawaii. Despite being a leading Native Hawaiian politician in this era, his legacy has been largely forgotten or portrayed in a negative light, mainly because of a reliance on English-language sources to write Hawaiian history. He was known by the nickname of "Pila Aila" or "Bila Aila" (translated as Oily Bill) for his oratory skills.[1][2] Born in Lahaina, Maui, of mixed Native Hawaiian and English descent, White was descended from Kaiakea, a legendary orator for King Kamehameha I. Representing Lahaina in the legislative assemblies of 1890 and 1892, he became a political leader for the Liberal faction in the government and established himself as a leader in the opposition to the unpopular Bayonet Constitution of 1887. Throughout the terms of both legislatures, White led attempts to pass bills calling for a constitutional convention. He was criticized by the missionary Reform party for his support of the controversial lottery and opium bills. He and Joseph Nāwahī co-authored the proposed 1893 Constitution with Queen Liliʻuokalani. They were decorated Knight Commanders of the Royal Order of Kalākaua for their service and contribution to the monarchy. When an attempt by the queen to promulgate this constitution failed on January 14, 1893, White's opponents falsely alleged he had tried to incite the people to storm ʻIolani Palace and harm the queen and her ministers. White denied these charges and threatened to sue the newspapers. Three days after the attempted promulgation, the queen was deposed in a coup during the overthrow of the Kingdom of Hawaii on January 17, 1893. During the Provisional Government of Hawaii and the Republic of Hawaii that followed it, he remained loyal to the monarchy. Returning to Lahaina, he helped organize native resistance on Maui and in 1893, was arrested for running out pro-annexationist pastor Adam Pali at Waineʻe Church.[3] He was elected in 1896 as honorary president of the Hui Aloha ʻĀina (Hawaiian Patriotic League), a patriotic organization established after the overthrow to oppose annexation. In 1897 he became an editor of the short-lived anti-annexationist newspaper Ke Ahailono o Hawaii (translated as The Hawaiian Herald) run by members of the Hui Kālaiʻāina (Hawaiian Political Association). Following the annexation of Hawaii to the United States, he was elected as a senator of the first Hawaiian Territorial legislature of 1901 for the Home Rule Party. Afterward, his political fortune declined with the party and his many attempts to win re-elections from 1902 to 1914 ended in defeats, although he was elected the first sheriff of Maui County for a brief period before his election was declared void due to inconsistencies in the 1903 County Act. Early life and familyWhite was born on August 6, 1851,[1][4][5] at Lahaina, on the island of Maui, to John Kahue White, Jr. and his wife Kahalelana.[6][7] His paternal grandparents were John White, Sr. and Keawe. He was of Native Hawaiian and English descent, thus known as a hapa-haole in Hawaiian and as a "half-caste" in the English press.[1][4][8][9] His paternal grandfather John White, Sr. was regarded as one of the oldest foreign-born residents in Hawaii at the time of his death. Known as "Jack" White, he was an Englishman originally from Plymouth, Devon. During the French Revolutionary Wars, he served on the frigate HMS Amelia. Sometime in 1796 or 1797, he arrived in Lahaina and later settled as a permanent resident in 1802. During the final years of the conquest and unification of the Kingdom of Hawaii, he served as a foreign advisor in the court retinue of King Kamehameha I. He received lands on Maui in the Great Mahele in 1848. After residing in the Hawaiian Islands for more than sixty years, he died on August 9, 1857.[10][11] He was living with his son-in-law, Maui sugar planter Linton L. Torbert (William's uncle), around the time of his death.[10]  From his paternal grandmother Keawe, he was descended from Kaiʻākea, his great-grandfather and an aliʻi (high chief) of Molokaʻi, who served as a political counselor, orator and many other different positions during the reign of the first Hawaiian king Kamehameha I.[4] In 1902, the Ka Nupepa Kuokoa printed a brief biography, noting: "... Kaiʻākea was a wise counsellor in ancient times in his occupation taught by his grandfathers from Kapouhiwaokalani to the sons, Mahinuiakalani and Kauauanuiamahi and Kuikai, on down to Kukalanihoouluae, the own father of Kaiʻākea. From these comes Kaiʻākea's political knowledge, that as an architect, an orator, a composer of the historical and genealogical chants, an important genealogical source for these islands and the one who by himself and with his chiefly children arranged the genealogy of the major chiefs of Hawaii, Maui, and Molokai from the high chiefly ranks to the low chiefly ranks."[12] During the 1860s, White was educated at the Luaʻehu School, the Anglican mission boarding institution run by Archdeacon George Mason in Lahaina. Founded by Anglican Rev. William R. Scott in 1863, this institution was a precursor of the present-day ʻIolani School in Honolulu. White was educated with Curtis P. Iaukea, Samuel Nowlein, Robert Hoapili Baker, and other future Hawaiian leaders.[13][14] White married the Chinese-Hawaiian Esther or Ester Apuna Akina (1855–1943), sister of fellow statesman Joseph Apukai Akina and sister in-law to Samuel K. Aki, a member of Hui Aloha ʻĀina.[15][4][8] They had five known children including Ellen Kananihemolele White (1875–1942), wife of politician David Kalei Kahāʻulelio, and Samuel Tensung Leialoha White (1886–1962), who became an assistant city engineer for Honolulu.[1][16][17][18] They adopted Esther's cousin, Chung Moy, who later became known as Nellie Rose White. Political career during the monarchyDuring the early 1880s, White worked as a police officer in Kohala, on the island of Hawaii. According to later opinions, he "made the reputation of being a good officer".[13][19] It was in this capacity that he first came into the political arena. In the general election of 1884 he was nominated as one of the many National (Governmental) Party members and ran for a seat in the Hawaiian legislative session of 1884, as a representative from Kohala. He received no votes in this election. Godfrey Brown (an Independent) defeated National Party member George Panila Kāmauʻoha, a colleague of White's in the Kohala police force at the time and also later a member of the 1892 legislature.[20][21] In April 1884, Kāmauʻoha was removed from his position for malfeasance and White was appointed his successor as deputy sheriff of North Kohala. Prior to this, the police department of Kohala had gained a reputation for corruption.[note 1] After his appointment, the new deputy sheriff became popular in the community for his competency, "strict attention to his duties, as well as his thorough integrity".[19] During his tenure, news reports claimed "he is acknowledged by all law-loving residents to be by far the best one we have had for many year, He is not to be bought, and is no respecter of persons or position, especially when the interest of the public are concerned.[19] However, he did not hold this position for long and was succeeded by J. W. Moanauli.[22] By 1885, White had moved to Hilo where he had begun practicing law.[23][24] He became an agent to take acknowledgements to instruments on September 12, 1884.[25][26] On January 1, 1886, he was listed as one of the speakers at a political rally at Halawa.[27] He later became a member of the Hui Kālaiʻāina (Hawaiian Political Association), a political group founded in 1888 to oppose the Bayonet Constitution and promote Native Hawaiian leadership in the government.[28][29] After the adoption of the constitution, White gave a speech in Hilo speaking out against it. He criticized the exclusion of the Chinese[note 2] and Japanese from the vote, especially focusing on the latter group because of Hawaii's treaty with the Empire of Japan.[30] By 1890, he had returned to his native island of Maui.[31] As a political leader, White received strong support in the Native Hawaiian community.[4] During his terms in the legislature, he became known by the nickname of "Pila Aila" or "Bila Aila" (Oily Bill) for his ability to speak to and humorously charm large crowds. He embraced this moniker although his opponents used it negatively to denigrate him as a slick, smooth-talking demagogue who negatively influenced his constituents.[1][2][9][32] In the Hawaiian tradition, his skills as an orator were attributed to the kuleana (responsibility) of his family as descendants of Kaiakea.[4] Legislature of 1890From 1890 to 1893 White served two terms as a member of the House of Representatives, the lower house of the Hawaiian legislature, for the district of Lahaina on the island of Maui.[33] In his first term, he initially ran as a member of the Reform Party against the National Reform Party candidate J. Nazareta. In 1887, the Reform Party (consisting of many descendants of American missionaries and Hawaiian conservatives) had become the established governmental party following King Kalākaua's coerced signing of the Bayonet Constitution. White was opposed to the constitution, and may have switched allegiance at a later point to the National Reform Party, which was established in opposition to the Reform Party in this session.[31][34] In a mass meeting at Palace Square on September 9, 1890, he allied with many other leading National Reform politicians in calling for a constitutional convention to draft a replacement for the constitution. Speeches were made by legislators Joseph Nāwahī of Hilo, John E. Bush, Robert William Wilcox and John K. Kaunamano of Oahu, and Luther W. P Kanealii of Maui, among other speakers. Reportedly, Representative Wilcox told the crowd that "any National Reform Party member of the legislature who voted against the convention bill 'ought to be torn limb from limb'". At the end of the meeting, White gave the final speech, which "made all who understood Hawaiian, laugh".[35] However, when the constitution convention bill went up for the vote of the legislature on October 1, it was defeated by a vote of 24 to 16.[36] White and Bush proposed a bill to the legislature to amend the 1887 constitution to give women the right to vote during this session. The bill did not pass. Had it been made into law, Hawaii would have preceded New Zealand as the first nation to allow women to vote. In 1892, Nāwahī would attempt to pass another bill supporting women's suffrage but it also failed.[37] The 1890 biannual session commenced on November 14. A few months later, in January 1891, King Kalakaua died while in San Francisco and was succeeded by his sister Queen Liliʻuokalani.[38] White and his wife Ester marched alongside other legislators and their spouses in the funeral procession of the deceased king.[39] Legislature of 1892–93 In 1891 White changed his party allegiance, joining the National Liberal Party. He and Wilcox were chosen as the stump orators to travel around the other islands and canvass for the new party.[40] The Liberal Party wanted increased Native Hawaiian participation in the government, as well as a constitutional convention to draft a new constitution to replace the unpopular Bayonet Constitution. However, the party soon became divided between radicals and more conciliatory groups. Joseph Nāwahī and White became the leaders of the factions of the Liberals loyal to the queen against the more radical members such as John E. Bush and Robert William Wilcox, who were advocating for drastic changes such as increased power for the people and a republican form of government.[41] Newspaper accounts noted that, during a meeting of Hui Kālaiʻāina on December 4, 1892, White reportedly said that he had "always abhorred the idea of a republic".[42][note 3] In the February 1892 election, White ran on the National Liberal ticket and defeated Reform candidate John W. Kalua for the seat of Lahaina in the House of Representatives.[43] From May 28, 1892, to January 14, 1893, the legislature of the Kingdom convened for an unprecedented 171 days, which later historian Albertine Loomis dubbed the "Longest Legislature".[44] This session was characterized by a series of resolutions of no confidence, resulting in the ousting of a number of Queen Liliʻuokalani's appointed cabinet ministers, and debates over the passage of the controversial lottery and opium bills.[45] During this session, White presented petitions for a new constitution from his constituents and introduced a bill on June 29 to convene a constitutional convention that was referred to a select committee. He supported the lottery bill and the opium bill, which were intended to alleviate the economic depression in the islands' sugar industry caused by the passage of the McKinley Tariff. The bills were controversial, dividing the legislators. He was one of three members to introduce an opium licensing bill (July 9) for legislative debate although the final bill adopted was another version written by Clarence W. Ashford. On August 30, he introduced the lottery bill, aimed at creating a national lottery system for raising governmental revenue, which was supported by the queen. According to Liliʻuokalani, White "watched his opportunity and railroaded the last two bills through the house". Both these bills passed the legislature after contentious debates.[46] Along with his political ally Nāwahī, White was decorated with the honor of Knight Commander of the Royal Order of Kalākaua at a ceremony in the Blue Room of ʻIolani Palace on the morning of January 14, for his work and patriotism during the legislative session.[47][48] The legislative assembly was prorogued on the same day, two hours later, at a noon ceremony officiated by the queen at Aliʻiōlani Hale, which stood across the street from the palace. The Daily Bulletin newspaper noted: "All of the Hawaiian members of the Legislature were present, and one of them, Rep. White, displayed a star of the Order of Kalakaua".[49] Overthrow As a strong proponent for a new constitution, White helped Queen Liliʻuokalani draft the 1893 Constitution of the Kingdom of Hawaii. Nāwahī was the other principal author, and Samuel Nowlein, captain of the Household Guard, was another contributor. These three had been meeting with the queen in secret since August 1892 after attempts to abrogate the Bayonet Constitution by legislative decision through a constitutional convention had proved largely unsuccessful. The proposed constitution would increase the power of the monarchy, restore voting rights to economically disenfranchised Native Hawaiians and Asians, and remove the property qualification for suffrage imposed by the Bayonet Constitution, among other changes. On the afternoon of January 14, after the knighting ceremony of White and Nāwahī and the prorogation of the legislature, members of Hui Kālaiʻāina and a delegation of native leaders marched to ʻIolani Palace with a sealed package containing the constitution. According to William DeWitt Alexander, this was pre-planned by the queen to take place while she met with her newly appointed cabinet ministers in the Blue Room of the palace. She was attempting to promulgate the constitution during the recess of the legislative assembly. However, these ministers, including Samuel Parker, William H. Cornwell, John F. Colburn, and Arthur P. Peterson, were either opposed to or reluctant to support the new constitution.[50] Crowds of citizens had gathered outside the steps and gates of ʻIolani Palace expecting the announcement of a new constitution. Among them were White and members of Hui Kālaiʻāina who had presented a sealed package containing the constitution.[51][52] After the ministers' refusal to sign the new constitution, the queen stepped out onto the balcony and asked the assembled people to return home, declaring "their wishes for a new constitution could not be granted just then, but will be some future day". Representative White also gave a speech to this crowd on the palace steps although the exact nature of what he said is disputed.[53] Opponents of the monarchy, especially the conservatives in the Reform Party, later claimed he gave an inflammatory and violent speech inciting the crowd to storm the palace and "go in and kill and bury" either the queen or her cabinet ministers. The speech may have been in Hawaiian and was only paraphrased in the English press.[51][54] On January 16, The Pacific Commercial Advertiser, an English newspaper in Honolulu, sympathetic to the Reform Party, reported:

The political fallout of the queen's actions led to citywide political rallies and meetings in Honolulu. Anti-monarchists, annexationists, and leading Reformist politicians including Lorrin A. Thurston formed the Committee of Safety in protest of the "revolutionary" action of the queen and conspired to depose her. In response, royalists and loyalists formed the Committee of Law and Order and met at the palace square on January 16. White, Nāwahī, Bush, Wilcox, and Antone Rosa and other pro-monarchist leaders gave speeches in support for the queen and the government. However, in their attempts to be cautious and not provoke the opposition, they adopted a resolution stating that "the Government does not and will not seek any modification of the Constitution by any other means than those provided in the organic law".[32][56] In this mass meeting, White also gave a speech denying the violent charges printed in the press against him, claiming that "the other fellows, meaning the Reformers, are crying out before they are hurt" (another paraphrasing published in The Daily Bulletin).[32] Minister Cornwell (one of the individuals the papers claimed he intended to harm) later stated in his testimony in the Blount Report:

Opposition to the overthrow and annexationThese actions and the radicalized political climate eventually led to the overthrow of the monarchy, on January 17, 1893, by the Committee of Safety, with the covert support of United States Minister John L. Stevens and the landing of American forces from the USS Boston. After a brief transition under the Provisional Government, the oligarchical Republic of Hawaii was established on July 4, 1894, with Sanford B. Dole as president. During this period, the de facto government, which was composed largely of residents of American and European ancestry, sought to annex the islands to the United States against the wishes of the Native Hawaiians who wanted to remain an independent nation ruled by the monarchy.[58][59] Resistance on MauiResidents of Maui began circulating petitions protesting the establishment of the Provisional Government in the districts of Wailuku and Makawao. White was still in Honolulu during the events of the coup d'état, and The Hawaiian Gazette reported rumors that he was one of the candidates for a Hawaiian embassy to Washington, DC, to ask for the restoration of the monarchy under the queen's niece Princess Kaʻiulani.[60] Departing Honolulu on February 7, he returned to Lahaina on the inter-island steamer Waialeale.[61] White remained a royalist and an agent of the deposed monarch on Maui and wrote "to the Queen and others about covert issues surrounding her possible re-instatement".[8][54][62] In May 1893 he helped organized the native community of Lahaina in removing the pro-annexationist Reverend Adam Pali of Waineʻe Church. Angered by the political stance of their pastor, the native congregation and the trustees of the church voted to remove Pali and asked him to vacate the residence owned by the church by July 8. However, these efforts were later undone by the central authority in Honolulu and the Maui Presbytery. During their meeting in June, the Hawaiian Evangelical Association (HEA) ruled against the vote of the native congregation. In July the Maui Presbytery reinstated Pali and excommunicated the members of the congregation, including White, who had voted to remove him.[63][64] The English press in Honolulu cast White in a negative light, claiming he had proved to be a "negative influence over the simple people of the parish".[9] On July 8 a confrontation took place between the leaders of the congregation, in physical control of the church, and supporters of Pali, which included Lahaina Circuit Judge Daniel Kahāʻulelio. Using his official position, Kahāʻulelio ordered the arrest of White and the four other leaders of the congregation on charges of "riot and unlawful assembly". They were imprisoned in the local jail to await trial. Represented by John Richardson, the personal attorney of the queen, their trial lasted three days, from August 2 to August 5, 1893. Judge William Henry Daniels, of the Wailuku Circuit Court, found no evidence that the defendants had organized or provoked a confrontation and acquitted them of the charges. Consequently, after Pali's reinstatement, church attendance at Waineʻe plummeted from seventy-five to thirteen members. The excommunicated members continued their resistance and worshipped at the nearby Hale Aloha Church instead.[64]  Waineʻe Church was burned down on June 28, 1894, after sparks from a rubbish fire ignited the wooden belfry of the church. Although the fire was accidental, annexationist Sereno Edwards Bishop, writing in 1897, blamed the Hawaiian royalists and those who had opposed Pali for the burning of the building. He stated: "The excellent pastor of this church, Reverend A. Pali, had become obnoxious to a majority of his people on account of politics. He had favored the abolition of monarchy, having become, like a majority of his colleagues in the pastorate, exceedingly disgusted with the increasing heathenish tendencies of the court. The dissension arising from Pali's attitude had led to the burning of the fine old stone church by partisans of the Royalist side, and the people were too weak to rebuild." This biased, false report has been repeated in the conventional history of Hawaii written with the use of English language sources. The church was later rebuilt and destroyed multiple times and was renamed Waiola Church in 1953.[65][66] Return to HonoluluWhite became a member of Hui Aloha ʻĀina o Na Kane (Hawaiian Patriotic League for Men), a patriotic group founded shortly after the overthrow of the monarchy to oppose annexation and support the deposed queen. A corresponding female league was also founded. The ranks of the men's group were largely composed of the leading native politicians of the former monarchy, including Nāwahī, who served as its president. A delegation (not including White) was elected by its members to represent the case of the monarchy and the Hawaiian people to the United States Commissioner James Henderson Blount sent by President Grover Cleveland to investigate the overthrow.[67] During this politically uncertain time, White traveled to Honolulu at the end of 1893 on the steamer W. G. Hall upon hearing rumors of the monarchy's restoration and returned to Lahaina in January when he discovered the reports were false.[68] The native resistance, the results of the Blount Report, and President Cleveland's refusal to annex the island stopped the annexationist scheme and prompted the Provisional Government to establish an oligarchical government, styling itself the Republic of Hawaii, until a more favorable political climate emerged in Washington.[69] In April 1894 White and John Richardson gave a speech at Lahaina opposing the new regime and asking the people not to participate in the election of delegates to the constitutional convention in Honolulu. Members of Hui Aloha ʻĀina gave speeches and held meetings across much of the island, and it was reported that foreigners and natives alike in Maui (with the exception of the residents of Hana) were strongly against the attempts to establish a republic.[70] At the beginning of January 1895, Robert William Wilcox launched a counter-revolution against the forces of the Republic. Its ultimate failure led to the arrest of many sympathizers of Wilcox and the militant efforts to restore the queen, including Liliʻuokalani and Nāwahī, who were arrested for misprision of treason. Nāwahī died in 1896 from tuberculosis complications contracted during his imprisonment.[71] After Nāwahī's death, White and other Hui Aloha ʻĀina delegates from the different island branches congregated in Honolulu for the election of a new leadership council on November 28, 1896, coinciding with Lā Kūʻokoʻa (Hawaiian Independence Day). In this meeting in which White presided as chairman, James Keauiluna Kaulia was elected as the new president. Two days later, White was chosen as the honorary president of Hui Aloha ʻĀina, over Edward Kamakau Lilikalani, by a majority of the assembled members. The Hawaiian Star reported, "In accepting the position Mr. White thanked the members for the honor and pledged himself to labor for the best interests of the society. He called upon the delegates to inform their constituents of his election and ask them to give him their cordial aid in his work."[72] In 1897 White became the editor of Ke Ahailono o Hawaii (translated as The Hawaiian Herald), a Hawaiian-language newspaper founded by Hui Kālaiʻāina. After the overthrow, this Hawaiian political group switched its political agenda toward opposing annexation to the United States and restoring Liliʻuokalani.[4][28] White co-owned the paper with David Keku and John Kahahawai.[73] The assistant editor was Samuel K. Pua, a colleague of White's in the 1892–93 legislature from Oahu, although Pua would resign in October of the same year.[74] At the conception of Ke Ahailono o Hawaii, the English newspaper The Independent noted that "The New venture under the control of Messrs. White and Pua, should indeed be a White Flower[note 6] of journalism, although the genial 'Sam' could change the euphony by adding another terminal vowel to his name."[76] The paper was published at Honolulu's Makaainana Printing House, owned by F. J. Testa.[76] Weekly issues were published from June 4 to October 29, 1897.[73] In May 1899 Testa sued White and the four other proprietors of the newspaper including David Kalauokalani (president of Hui Kālaiʻāina) for unpaid printing costs of the short-lived paper. The court ruled in favor of Testa awarding him the amount of $743,40, although White was only required to pay one-fifth of $447.50 because he left the venture when the "troubles" started. The decision was reversed on appeal.[77] After assuming office in 1897, United States President William McKinley signed the treaty of annexation for the Republic of Hawaii, but it failed to pass in the United States Senate after the Kūʻē Petitions were submitted by Kaulia, Kalauokalani, John Richardson and William Auld as evidence of the strong resistance of the Native Hawaiian community to annexation. Members of Hui Aloha ʻĀina collected over 21,000 signatures opposing an annexation treaty. Another 17,000 signatures were collected by members of Hui Kālaiʻāina but not submitted to the Senate because they were asking for the restoration of the queen and the delegates. The petitions were used as evidence of the strong resistance of the Hawaiian community to annexation and the treaty was defeated in the Senate. After the failure of the treaty, Hawaii was instead annexed by means of a joint resolution called the Newlands Resolution, in July 1898, shortly after the outbreak of the Spanish–American War.[28] In September 1898 White took an oath of allegiance to the United States and the Republic of Hawaii in order to renew his license to practice law in the inferior courts of the Hawaiian Islands.[78] A few days later on September 12, David Kalauokalani, Robert William Wilcox and other members of Hui Kālaiʻāina held a meeting at the Palace Square. White was slated as a possible speaker at the meeting, in the newspaper The Hawaiian Star printed the morning of September 12, although it is not certain if he attended the meeting later in the evening. Many Hawaiians had accepted annexation was to stay. Despite divided opinions among the Hawaiian leaders, they sent a memorial requesting the restoration of the monarchy and "the old order" to the board of commissioners established to finalize the laws and annexation of the islands to the United States.[79] Territorial governmentFollowing the establishment of the Territory of Hawaii in 1900, White became a member of the Home Rule Party, which was formed by the former leaders of Hui Aloha ʻĀina and Hui Kālaiʻāina. The party consisted of Native Hawaiians who had been leaders during the monarchy and other former royalists and loyalists such as Robert William Wilcox, who was elected the first congressional delegate from Hawaii under the Home Rule ticket. During this period, the party would share the political stage and contend with the Republicans and Democrats.[80] 1901 legislature  There had been speculation since May 1899 that he would be a candidate for office in the new territorial government.[81] In November 1900 election White was elected to the inaugural Territorial legislature, established under the Hawaiian Organic Act, as a senator from the Second District (corresponding to Maui, Molokaʻi. Lānaʻi, and Kahoʻolawe).[82] During this term, his brother-in-law, Joseph Apukai Akina, would serve as Speaker of the House of Representatives while his son-in-law David Kalei Kahaulelio served as sergeant-at-arm of the Senate.[13][33] During this session, the Native Hawaiian legislators attempted to pass new laws in the interest of the local people, who included Hawaiian taro farmers, patients of the Kalaupapa Leprosy Settlement and victims of the 1900 Chinatown fire, among others. In total, fifty-one bills were introduced in the Senate and one hundred and twenty-six in the House, although only nineteen bills were submitted by both houses for ratification. They proposed creating a governmentally funded education program for poor Hawaiian students similar to the Education of Hawaiian Youths Abroad program initiated during the reign of King Kalākaua. A pension for the deposed Queen Liliʻuokalani and appropriation to repair the Royal Mausoleum of Hawaii were also proposed. They promoted the use and study of the Hawaiian language, especially in the government and courts. Ignoring the Organic Act which mandated the sole use of English in the legislature, this session was conducted in both Hawaiian and English with the aid of an interpreter. Many of the territorial legislators in this session did not speak English. They also created the first county bill, which would have created five counties named after former Hawaiian aliʻi.[83][84][note 7] However, their agenda was obstructed by the Republicans and the appointed members of territorial government, especially Governor Sanford B. Dole, the former president of the Republic. In this session, the Home Rulers attempted to decentralize control away from the governor and empower local government by passing a bill creating the first counties in Hawaii. This county bill was defeated by Dole through a pocket veto after the prorogation of the regular session.[83][84] The legislative assembly was later mockingly dubbed the "Lady Dog Legislature" because of extensive debate on House Bill No. 15,[note 8] which pertained to the repealing of an 1898 tax on ownership of female dogs. This nickname was used by opponents of the Home Rulers to denigrate the group and the difficulties of the 1901 legislature would later be used as evidence of the incompetence of Native Hawaiian political leadership.[87][88][89] Historian Ronald William, Jr., noted:

Declining political career In the next election, for the 1903 legislature, White ran again for senator on the Home Rule ticket. Despite expecting an easy victory, he was defeated by Republican candidate Charles H. Dickey. White accepted the defeat graciously.[91] Many Home Rule members of the previous legislature also lost, including his brother-in-law Speaker Akina. Referring to these defeated politicians as the "Lady Dog Members", The Hawaiian Star reported "all went down to defeat on their Lady-Dog record".[89] During this same election, Prince Jonah Kūhiō Kalanianaʻole, who bolted from the Home Rule Party with many of his followers to join the Republicans, defeated Wilcox for the position of Hawaii's delegate to Congress, resulting in the decline of the Home Rule Party and allowing the Republicans to gain the upper hand.[91][92] A second county bill was passed by the 1903 legislature and approved by Governor Dole, forming Maui County and four other counties on the main Hawaiian Islands.[93][note 9] The first local territorial elections for the county boards of Maui and the other counties were held on November 3.[95] In this election, White ran as the Home Rule candidate for Sheriff of Maui County and defeated the Republican candidate Lincoln M. Baldwin, who had held the previously appointed position of sheriff. The Home Rule Party ended up dominating in the local elections on Maui.[96][note 10] Shortly after his election, White and David Haili Kahaulelio,[note 11] the elected county clerk for Maui, wrote to Dole's successor, Governor George R. Carter, asking him to assemble a conference where the newly elected county officials across the territory could discuss how the county governments should be conducted.[100] The county act came into effect on January 4.[93][101] However, it was soon placed on hold by the Hawaii Supreme Court, awaiting a ruling on its constitutionality. Acting under the instruction of the governor, High Sheriff Arthur M. Brown ordered the former appointed sheriffs to resume their posts from the elected officials. Brown sent a telegraph, on January 14, to Sheriff Baldwin ordering him to resume his former position and asking White to vacate his office.[102] They expected some amount of difficulty from White, and Brown considered sending a force from Honolulu under Deputy High Sheriff Charles F. Chillingsworth to quell any possible insurrection. Baldwin assembled men from his former police force and retook the sheriff's office, but White refused to relinquish his position, insisting that he wanted "further advice from the Attorney General as to what he should do". The board of supervisors met and decided that White should hold office until there was an official notification from Honolulu on the matter. Both Baldwin and White agreed to wait. On January 16, 1904, the Hawaii Supreme Court ruled the second county bill as unconstitutional because it ran counter to the Organic Act, effectively voiding the previous local elections. When the official decision was received, White resigned as sheriff.[93][103] Permanent county governments were finally established by an act of the following legislature of 1905. Opting to run for the lesser position Deputy Sheriff of Lahaina, White lost the county election of June 1905, to the Republican Charles R. Lindsay, Jr. by a margin of 112 to 212. Republican William E. Saffery was elected as the sheriff of Maui County. The election resulted in overwhelming Republican victory with only two Home Rule victories in Wailuku for county supervisor and deputy sheriff.[104][105]  The rest of White's political career was marked by a successive period of electoral defeats caused by his continued adherence to the declining Home Rule Party. In November 1904 he ran for the territorial senate for a third time, on a dual Home Rule and Democratic ticket. However, since 1903 the Home Rulers had been steadily losing power to the Republicans, and White was defeated by Republican candidate Samuel E. Kalama by a margin of 810 to 1311.[92][106] In 1906 he ran for the territorial senate for a fourth time, as a Home Ruler. His supporters described him as "Safe, sane, and conservative" in their petition letters nominating him for the election. However, he was defeated again by the Republican candidate William J. Coelho by a narrow margin of 1225 to 1281.[107] After relocating to Oahu in 1907, he returned briefly to Maui to run as a Democrat in the 1908 election for the senate seat from Maui, but was defeated by a margin of 1152 to 1158.[1][108] In Honolulu, he ran in the general elections of 1910 and 1912, as a senator for the fourth and fifth district of Oahu, on the Home Rule ticket, but he performed poorly in both elections.[109][110] The Home Rule Party formally disbanded in 1912 although a few candidates, including White, unsuccessfully ran in the primary elections of 1914.[92][111] Election recordsFollowing is the election records from 1884 to 1914 based on the results published by English language newspaper in Hawaii.

Death and legacy From 1901 to 1903 White was the proprietor of the Ka Lei Nani Saloon in Lahaina, which was advertised in The Maui News.[116] In later life, he moved from Lahaina to Honolulu in 1907. After an illness of eight months, he died on November 2, 1925, at his home at 604 Kalihi near North Queen, in Honolulu.[1] He was buried in an unmarked grave at the Kaʻahumanu Society Cemetery, next to where his widow (a lifelong member of the society) would later be laid to rest.[15][117][118] In 2017, historian Ronald William, Jr. raised the funds for a marker for White's grave through a GoFundMe campaign. The grave marker was unveiled on August 6, the anniversary of White's birth.[119] Despite his popularity in the native community, White was portrayed negatively in the English-language press in his lifetime and in the published histories after his death.[54] As a consequence of his opposition to the powers that overthrew the monarchy and later annexed the islands to the United States, White remains obscure in Hawaiian history.[8] Recent research efforts in Hawaiian academia using Hawaiian language sources have shed more light on White and many other early Native Hawaiian resistance leaders like him.[54][120] In Hawaii's Story by Hawaii's Queen, Liliʻuokalani praised the work of Nāwahī and White:

Honors

Notes

References

Bibliography

Further reading

External links

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||