|

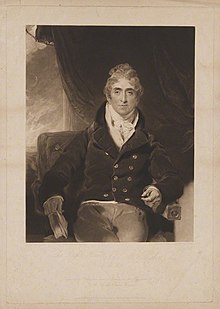

William MacMahonSir William MacMahon, 1st Baronet (1776–1837) was an Irish barrister and judge of the early nineteenth century. He was a member of a Limerick family which became politically prominent through their influence with the Prince Regent, later King George IV. He was the first of the McMahon Baronets of Dublin. BackgroundHe was born in Limerick, son of John MacMahon, comptroller of the port of Limerick, and his second wife, Mary Stackpoole, daughter of James Stackpoole, a merchant; his father's relatively low social standing was something of a handicap to his career. Born a Roman Catholic, he converted to the Church of Ireland for career purposes. He is not thought to have supported Catholic Emancipation, and later quarrelled with Richard Lalor Sheil, who was a relative by marriage, on the subject. He was educated at Trinity College Dublin, and called to the Bar in 1799, practising on the Munster circuit. He was made Third Serjeant-at-law in 1806, Second Serjeant in 1813 and King's Counsel in 1807. Despite what was called his "spluttering" manner, and a tendency to verbal gaffes, he built up a very large practice, second only to that of Daniel O'Connell,[1] whom he remembered with gratitude for having befriended him, at a time when most other barristers looked down on him as the son of a minor official. Family and political connections William married firstly Frances Burston, daughter of Beresford Burston K.C., who died in 1813; and secondly Charlotte Shaw, daughter of Sir Robert Shaw, 1st Baronet of Bushy Park, Dublin and his first wife Maria Wilkinson. Of his ten children, who included his heir Sir Beresford Burston MacMahon, 2nd Baronet, the most notable was his third son Charles MacMahon (1824–1891) who had a distinguished career in Australia as a politician, and who was the second Chief Commissioner of Victoria Police from 1854 to 1858. Charles MacMahon was also Speaker of the Victorian Legislative Assembly between 1871 and 1877.[2] Although William married into two prominent Dublin families, the Burstons and the Shaws of Bushy Park,[3] his most valued relative was undoubtedly his much older half-brother, Sir John McMahon, 1st Baronet (1754–1817) who in 1811 was appointed private secretary to the Prince Regent, later King George IV, and who in the remaining six years of his life had great influence over the Prince. He was thus able to obtain favours for his family: William noted cynically that barristers who had previously despised his family's lowly origins now began fawning on him.[4] When John Philpot Curran retired as Master of the Rolls in Ireland John was able to obtain the office for William, who was only 37; this is said to be one of the few occasions when the British Royal family has directly intervened in a judicial appointment. William, like his brother, became a baronet. From 1811 he lived at Fortfield House, Terenure, County Dublin, which had been built in 1805 by Barry Yelverton, 1st Viscount Avonmore. William had another brother Sir Thomas McMahon, 2nd Baronet, who succeeded to John's title by special remainder, and at least one sister, Mrs. O'Halloran. Her daughter, whose first name is apparently forgotten, was the first wife of the writer and politician Richard Lalor Sheil. William opposed the marriage due to what he regarded as Sheil's extreme nationalist and pro-Catholic opinions. Mrs. Sheil died in childbirth in 1822, leaving a son who died young. The distinguished army officer Sir Edward Grogan, 2nd Baronet (1873-1927) was William's great-grandson, his mother being Charlotte MacMahon, a daughter of Sir Beresford MacMahon.  Judicial career and reputationIn previous centuries the office of Master of the Rolls in Ireland had been a notorious sinecure for politicians, who were not necessarily lawyers, or even Irish. However, the appointment of Sir Michael Smith in 1801 had been made in an effort to turn the office into a full-time judicial position which would attract first-class lawyers. Given William's youth, and the blatant nepotism involved in his appointment, it might have been expected to cause controversy. In fact, according to Elrington Ball, there was no protest and the appointment worked out far better than had been feared: William had a reputation for integrity, was popular and hospitable, and a fairly good lawyer.[5] An obituary notice published soon after his death in January 1837 bears Ball's assessment out: MacMahon was praised for integrity and lack of political prejudice and as an exceptionally painstaking and conscientious judge; while the writer admitted that William was very slow in giving judgment, this was attributed to his desire to ensure that justice was done.[6] In 1827 he clashed publicly with the new Lord Chancellor of Ireland, Sir Anthony Hart, about his right to appoint his own secretary, but the misunderstanding was quickly resolved. References

|