|

William Colenso

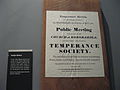

William Colenso (17 November 1811 – 10 February 1899) FRS was a Cornish Christian missionary to New Zealand, and also a printer, botanist, explorer and politician.[1] He attended the signing of the Treaty of Waitangi and later wrote an account of the events at Waitangi.[2] LifeBorn in Penzance, Cornwall, he was the cousin of John William Colenso, bishop of Natal. His surname is locative and it originates from the place name Colenso in the parish of St Hilary, near Penzance in west Cornwall.[3] He trained as a printer's apprentice then travelled to New Zealand in 1834 to work for the Church Missionary Society as a printer/missionary.[4] He was responsible for the printing of the Māori language translation of the New Testament in 1837. It was the first book printed in New Zealand and the first indigenous language translation of the Bible published in the southern hemisphere.[5] By July 1837, he had printed and bound 2,000 copies of the Epistles to the Ephesians and Philippians, as well as printing addition, multiplication, and shillings-and-pence tables for the schools.[6] Then by 5 January 1836, he had composed and printed 1,000 copies of St Luke's Gospel, as well as further material for the schools.[6] In July 1837, Colenso printed the first Māori Bible comprising three chapters of Genesis, the 20th chapter of Exodus, the first chapter of the Gospel of St John, 30 verses of the fifth chapter of the Gospel of St Matthew, the Lord’s Prayer and some hymns.[7][8] During the year ending 31 December 1840, he had printed 10,000 Catechisms, 11,000 Psalms, other religious texts and material for the schools; as well as 200 copies of the New Zealand Gazette for the colonial government.[8] On 5 February 1840, Colenso recorded and interpreted Māori chiefs (rangatira) debating the Treaty of Waitangi (Te Tiriti o Waitangi) in Waitangi.[2] Before the first signings of the treaty the next day, Colenso interpreted some of the Māori speakers for Hobson, warned him that Māori he had spoken to did not understand the Treaty,[9] and asked for the orally-agreed Article Four of the Treaty to be added in writing.[10] He was ordained a Deacon on 22 September 1844 following his theological studies at St John’s College, which was then located at Te Waimate mission.[11] He was an avid botanist; detailing and transmitting to Kew Gardens in England previously unrecorded New Zealand flora. He assisted Joseph Dalton Hooker when he visited the Bay of Islands from 18 August to 23 November 1841.[12] In 1866, he was the first New Zealander to be elected as a Fellow of the Royal Society. He wrote several books, and contributed over a hundred papers to scientific journals. He married Elizabeth Fairburn on 27 April 1843. William and Elizabeth Colenso worked at the Waitangi (between Clive and Awatoto, Napier)[13][14] Mission from 1844. In the 1840s, from his mission station in Hawke's Bay, Colenso made several long exploratory journeys through the central North Island in the company of Māori guides with the aim of reaching the inland Māori settlements of Patea, in the Taihape region, and converting them to Christianity.[15] His travels took him through trackless forest, over the high Ruahine Range and across the Rangipo Desert and past the mountains of Ruapehu and Tongariro to the shores of Lake Taupō. His use of existing Māori routes into the interior contributed greatly to the European exploration of the central North Island.[16] One of his journeys, between December 1841 and February 1842, was across the North Island and up to the Kaipara Harbour.[17] From 1845, Colenso undertook lengthy journeys every spring and autumn. In 1847, he travelled to Taupō then south to pass by the Tongariro and Ruapehu mountains. He visited regularly the Wairapara and Hutt districts,[18] where he was frequently at odds with the European lessees of sheep and cattle stations such as Kelly, McMaster, Grindell and Gillies. In 1845, about a dozen sheep and cattle farmers had leased large areas of land from local Māori by mutual agreement. Māori owners regularly raised the annual lease fee to the annoyance of the farmers. The farmers regularly pressed Māori to sell land. Many younger chiefs were keen sellers but were thwarted by conservative older chiefs. The farmers also paid Māori to assist in building roads to help economic development. Colenso regularly counselled Māori against selling any land or helping build roads which he claimed would be disastrous for them. Colenso was especially vociferous about the farmers living with Māori women as their wives, without a Christian marriage. Colenso also had strong views about drinking and horse racing which were a regular part of colonial life that Māori as well as settlers enjoyed. This put him in opposition to a wide range of New Zealanders. In 1847, Judge Chapman, Doctor Featherston, the bank manager McDonald and the merchant Waitt visited the Hutt valley. There was criticism of what was called "the malicious interference of Colenso".[19] His standing in New Zealand colonial society and the Church Missionary Society, along with his fervent hope of ordination, was lost when it was discovered that he was the father of a son (Wiremu) by Ripeka, the Māori maid of his wife, Elizabeth Colenso, in May 1850.[4][20] In November 1851, Colenso was suspended as a deacon and dismissed from the mission in 1852.[21] Te Roore Neho claims to be descended from Colenso and "a high-ranking Māori woman", Tihi Awarua of the Ngāti Mahia hapū (subtribe) of Ngāpuhi, through a son born in 1841, and that there are now more than 2000 descendants, Neho being short for Koreneho, the transliteration of Colenso into Māori.[22] It might, however, be merely a baptismal name.[23] Diaries from the mid-period of Colenso's life were destroyed in circumstances suggesting they told of other indiscretions.[24] In 1853, he was convicted of a technical assault over an argument about Ripeka and their son.[25]

Following a long wilderness period during which he continued his botany work, he took an active role as a local politician in Napier. He represented Napier as the Member of Parliament for the Napier electorate from the 1861 by-election to 1866, when he retired.[26] In 1871, Colenso was the speaker at the Hawkes Bay Provincial Council when Ngāti Kahungunu had been persuaded by farmers, the Russell Brothers, that they could get their land back in what came to be known as the Repudiation Movement. Their chief Henare Matua had already pronounced all land dealing with both the crown and private sales illegal. The brothers persuaded Māori that legal action against large land owners such as Donald McLean would succeed. Colenso advised Māori not to take a legal path that would leave them deep in debt. Lawyer and later Government Native Minister John Sheehan, who spoke fluent Māori,[27] acted on behalf of the Repudiation Movement. Matua attempted to stand as an MP but lost and the movement, deep in debt, petered out.[28] In 1890 he published a first-person account of the signing of the Treaty, at which he had taken extensive notes.[29] He died in Napier in 1899, leaving two sons and a daughter. His son from Ripeka, Wiremu/William, left New Zealand for Cornwall, married a cousin and lived in Penzance until his death. His son from Elizabeth Fairburn, Ridley Latimer, attended St John's College, Cambridge, and finally settled in Scotland.[30] His daughter Frances Mary married William Henry Simcox and settled in Ōtaki, New Zealand. He left Francis £2000 in cash, Latimer most of his estate and £200 in cash; Latimer sold quickly or destroyed most of his collections.[31] Neither of his sons had surviving children – Frances had nine. CommemorationMany species have been named in honour of Colenso including Acrothamnus colensoi.[33] Colenso SocietyFounded in 2010 by academics and historians across New Zealand, the Colenso Society aims to "promote the study of the life and work of the Reverend William Colenso FLS FRS".[34] Published work

Gallery

Notes and references

External links

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||