|

William Augustus Muhlenberg

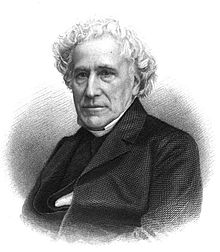

William Augustus Muhlenberg (September 16, 1796 – April 8, 1877) was an Episcopal clergyman and educator. Muhlenberg is considered the father of church schools in the United States. An early exponent of the Social Gospel, he founded St. Luke's Hospital in New York City. Muhlenberg was also an early leader of the liturgical movement in Anglican Christianity. His model schools on Long Island had a significant impact on the history of American education. Muhlenberg left his work in secondary education in 1845. BiographyMuhlenberg was born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, on September 16, 1796. He was a great grandson of Henry Melchior Muhlenberg (1711–1787, known as the father of Lutheranism in America) and a grandson of Frederick Muhlenberg (1750–1801), a member of the First and Second Continental Congresses and Speaker of the House of Representatives. Although baptized Lutheran, He grew up Episcopalian, attending St. James' Episcopal Church.[1] Muhlenberg was educated at the Philadelphia Academy and the Grammar School of the University of Pennsylvania, graduating from the university in 1815. In 1817 he was ordained a deacon in the Protestant Episcopal Church, becoming assistant to Bishop William White (1748–1836) in the rectorship of Christ Church, St. Peter's and St. James' in Philadelphia.[2] At this time Muhlenberg was influenced by his older friend, Jackson Kemper (1789–1870), who became the first Missionary Bishop of the Protestant Episcopal Church in 1835. In 1820, Muhlenberg was ordained a priest, and until 1826 he was rector of St. James' Church in Lancaster. Largely due to his efforts, Lancaster was the second public-school district created in the state. His interest in church music (particularly hymns) prompted his 1821 pamphlet, A Plea for Christian Hymns, and he compiled Church Poetry in 1823 for his parish. That year Muhlenberg was appointed by the General Convention to its committee on psalms and hymns. Its collection (approved in 1826) contained several of Muhlenberg's compositions, including I Would Not Live Alway, Shout the Glad Tidings and Saviour, Who Thy Flock Art Feeding.[2]  Church-school movementFrom 1826 to 1845, Muhlenberg was rector of St. George's in Flushing, Queens. In 1828 he became "Principal" of the "Church Institute" in Flushing, where he initiated a unique and highly successful method for the education of boys. In 1836, the cornerstone was laid for a new educational enterprise a mile north of Flushing. This more ambitious initiative was named St. Paul's College and Grammar School.[1] (College Point in present-day Queens County NY is where Muhlenberg's school was situated.) Richard Upjohn designed a magnificent main building. The foundations for the building were completed by 1837 and the edifice of pink stone and white marble began to rise on the hill above Long Island Sound. It was not only the unfortunate financial Panic of 1837 but the party squabbling within the Episcopal Church that prevented Muhlenberg from collecting on the pledges to capitalize and endow St. Paul's. Without adequate endowment, the state legislature denied Muhlenberg's request for a collegiate charter, which meant that St. Paul's could not legally grant the degree of Bachelor of Arts. The ruination of St. Paul's left a lasting wound in Muhlenberg's heart. One of the greatest educators in American history—admired by even public school promoters—departed Long Island for good in 1847. The property was sold a few years later.[3] But Muhlenberg's philosophy and practice of education had already been handed over to younger men who made a monumental contribution to the history of American education (see John Kerfoot, James Lloyd Breck, and Henry Augustus Coit). Educational principlesMuhlenberg rejected "vague, spiritualized Christianity."[4] His schools blended home, school and church.[5] These Episcopalian communities considered literature, the sciences, and moral education equally in order to mold Christian character rather than pursuing academic excellence alone.[6] Muhlenberg defined character as not only moral goodness, but also the qualities, skills and attitudes favoring effectiveness in the world (for example, to manage a challenging course of study). Academic excellence would inevitably follow. His schools were Christian families, with Christ as the head, and by church school he meant a part of the Body of Christ in which divine grace (God's help) was present for the believer. Muhlenberg and his successors considered the school as the scholastic church. A practical Christian, his Christianity was more practice than theology. Echoing John Henry Newman, Muhlenberg believed that "Christianity can not be inculcated in the abstract."[7] One of the least sectarian religious leaders of his generation, he realized that unless a religious school teaches a particular religion it would become secular or splinter into factions. A lasting, healthy religious tolerance in a community is enabled by a religious center (or established discipline) from which hospitality and tolerance radiate to the community. Muhlenberg's experience in public schools from 1818 to 1826 impressed him with the importance of Christian education, and he wanted the Flushing school to build Christian character with denominational instruction. In his 1828 pamphlet The Application of Christianity to Education, he assumed that a moral education would be based on Christianity because of his belief that God revealed himself in a particular way through Jesus Christ. Muhlenberg was confident that through the Bible, humans can glimpse the will of God and a moral education is based on knowledge of that will. A classical scholar familiar with moral goodness in the pagan world, to him the Gospel and Christianity were true and the best education would incorporate them. To Muhlenberg, virtue was synonymous with Christ. According to his 1828 pamphlet, "The Law of God is the law of the school" as a pattern or blueprint. Muhlenberg strongly discouraged public comparison of weaker to stronger students, and rarely administered corporal punishment; both distinguished him from most contemporary American educators. The schools at Flushing and College Point were happy, busy scholastic brotherhoods. James Lloyd Breck (1818–1876) spent five years on Long Island with Muhlenberg and his staff. Although considered an ordinary student, he entered the University of Pennsylvania as a third-year student and graduated magna cum laude the following year. After divinity school, Breck went west and founded three seminaries (including Nashotah House Episcopal Seminary in Wisconsin), four boarding schools, three colleges and twenty parochial schools (including Shattuck-St. Mary's School in Faribault, Minnesota). Well-versed in the spread of Christianity during Late Antiquity, he was a missionary among the Mississippi Chippewa in the North Woods of Minnesota and established Muhlenberg-type schools for Ojibwe students. For Muhlenberg, education was holistic and comprehensive. His application of Christianity to education resembled the aims of Horace Mann (1796–1859) and Thomas Arnold's work at Rugby School beginning in 1828. Foreshadowing John Dewey, Muhlenberg wrote: "Some great minds are slow in developing, the acorn gives little promise of the oak"[8] and "The head should not be furnished at the expense of the heart."[9] He and his scholastic heirs did not allow religion to usurp academic rigor and high scholastic standards: "Religion should never be held to account for inferior scholarship."[10] According to Henry Coit (1830–1895), a disciple of Muhlenberg, "A high aim is better than a low one." Stepping back and taking a good philosophical look at what Muhlenberg and company achieved, we can see that they successfully applied Christianity to the 2,500-year-old perennial philosophy of education in the west. Muhlenberg’s approach may be called “the high-aim philosophy of education.” The target of the perennial philosophy is Virtue. Socrates, Plato, Aristotle, et al., assumed that, if the target is Virtue, then all the other “natural goods” (Aristotle) will come to the student in time and as a matter of course. Against the Sophists, these sages defined Virtue not as skill or proficiency in a particular art (e.g. accounting) but as skill and proficiency in being human as such. Since Virtue is general human excellence, education must in every way aim for that goal. A school must be tooled up to educate the whole person to excellence. As far back as the 1820s, WAM noticed the deep imbalance in education. Much emphasis was placed upon educating the “head” while less and less time was given to the other aspects of human nature – the “heart.” The west still suffers from this bias. What the philosopher Charles Taylor and other observers call “the commercial culture” gave rise to many things, one of them “rationalism,” which may be defined as the inordinate self-reliance of the rational creature. WAM saw two hundred years ago that this rationalism was creating a huge imbalance in education. His response was not prolix treatises on education but two innovative and immediately successful schools on Long Island: The Church Institute at Flushing (1828) evolved into St. Paul’s at College Point (1836), one mile north of Flushing. But WAM and company knew they faced a problem. Christians hold that Christ Jesus established and embodied a new standard of Virtue in the world and only Christ is Virtuous; so how can a human being attain that Virtue, since human nature is severely debilitated by what all the religious traditions call “sin”? WAM understood that, if Christ is our Virtue, then incorporation into Christ in some mysterious way must be the means by which human beings can attain Virtue. In the “Muhlenberg-type Church school,” ‘Church’ does not then denote a particular denomination or a mere institution; it denotes the living Body of Christ in this world, the “one, holy, catholic, and apostolic Church” of the Creed. The Church as the Body mystical of Christ is the “place” where human beings become part of or members of Christ. Hence the Church school is the Church in its scholastic mode. Of course, the Church is not a school, and the school is not a church. The two should never be confused. Yet in the bona fide Church school God’s grace is constantly mediated in Christ to and by each member of the Body scholastic; every member of the Body is mysteriously incorporated, “little by little,” into Christ; and in this way high standards can be set and Virtue attained by participation in Christ. "Participation" and "incorporation" were once a leading feature of Anglican theology. Muhlenberg realized, however, that "there can be no such thing as Christianity in the abstract." Christianity is not a philosophy but a matter of daily practice. Teachers and administrators in the scholastic fellowship must have something, some culture, to hand over to the students. In this way, a school of a particular religious tradition has many advantages. Daily life is more natural, less forced, and the religious culture is handed down "by osmosis." Hence while Muhlenberg and his disciples were less sectarian than anyone in their generations, they saw the wisdom of equipping the schools with the doctrines and usages of what we would call the Episcopal "denomination," which they considered very broad and ecumenical. The Catholic Church, the Orthodox, the Protestant churches, should do the same, Muhlenberg and company would say. It is a practical matter at the same time that the approach comprehends the many mysteries that comprise Christianity. Impact on American educationMuhlenberg's Flushing Institute and St. Paul's College failed due to inability to weather the 1837 financial crisis in the United States. However, his pedagogical vision was transported to other regions by his protégés.[11][12] In 1842 he helped found Saint James School in St. James, Maryland, with his assistant at St. Paul's College and Grammar School, John Barrett Kerfoot, who later became the first bishop of Pittsburgh and founded Trinity Hall School for Boys (1879) using Muhlenberg's principles.[13][14] For his work in education, Kerfoot received an honorary doctorate from Cambridge University. Henry Augustus Coit (1830–1895), a former student of Muhlenberg and Kerfoot, was the founding rector of St. Paul's School in Concord, New Hampshire (1856). Kerfoot's nephew was the founding headmaster of St. Mark's School in Southborough, Massachusetts (1865). Endicott Peabody (1857–1944) founded Groton School in 1884; acknowledging Muhlenberg's influence, he kept his portrait in his study and referred to Groton as a "church school". The founders of St. George's School in Rhode Island (1896) also cited Muhlenberg as an educational pioneer, and he influenced the 1839 founding of the Episcopal High School in Alexandria, Virginia. Muhlenberg consulted with EHS founding headmaster William Nelson Pendleton, and sent acolyte Milo Mahan (who taught at St. Paul's in College Point) at the request of the Bishop of Virginia. Historian James McLachlan noted the Muhlenberg schools' uniqueness in American Boarding Schools: A History (1970). Religious beliefsMuhlenberg's religion can be difficult to describe. His mature religion may be described as Anglican Christianity with an American accent. He was claimed by different parties within his denomination—the High Church, the Evangelical, the Low Church—but proceeded in his own way. In some respects, he was an early example of what came to be called the Broad Church. He opposed the "novelties" of Roman Catholicism and dogmatic Protestantism, affirming the Scriptures and church teaching before the 11th-century East–West Schism. Muhlenberg echoed the 17th-century Anglican bishop John Cosin who wrote that his Anglican church was "Protestant and Reformed ... according to the Ancient Catholic Church."[citation needed] His position was also similar to Edward Bouverie Pusey (1800–1882), an Oxford professor and a leader of the 19th-century revival movement in the Church of England. Muhlenberg was influenced by the Oxford Movement, William White (1748–1836), John Keble, John Henry Newman, Pusey,[15] Richard Hooker (1554–1600) and the Christian tolerance of Jeremy Taylor (1613–1667). As a youth, Muhlenberg worked to become quite familiar with the Fifteen Sermons and Analogy of Religion of Bishop Joseph Butler (1692–1752). Trained in Philadelphia by William White and prepared for ordination by Jackson Kemper, he began to call his religion "Evangelical and Catholic" in the late-1840s and published a newspaper of that name in the 1850s. [citation needed] By "evangelical," Muhlenberg meant personal devotion to Jesus Christ, dedication to the Scriptures as the Word of God, and the responsibility to live and share the Gospel. "Evangelical" connoted what is spontaneous and Spirit-led about Christianity. By "Catholic," Muhlenberg meant the "bones" of the Faith: tradition, creeds, liturgy, and sacraments. Newman's eight-volume Parochial and Plain Sermons parallel many of Muhlenberg's views. Muhlenberg worshiped Christ without sentimentality, believing that Jesus lived in his schools, his parish church, and in St. Luke's Hospital, New York, where he ministered to the sick and dying. When he created St. Johnland on Long Island late in his life, he would say that the primary study in the educational programs there was "Jesus." The history of persons and of institutions is a diachronic phenomenon; time does not stand still and everything changes. Muhlenberg's faith and practice developed over the decades. He was a born reformer and did effect reforms in the PECUSA. He inspired many High Churchmen and those who came to be called "Anglo-Catholics," but he was neither a High Churchman nor an Anglo-Catholic. He was well known as an innovator of divine worship but was never a true "ritualist." The ritualism he introduced in his school chapels had one purpose: to impress upon the minds of his boys the great doctrines of Christianity. The concept worked to good effect. It was as much a Lockean as an Anglo-Catholic idea: He wanted to give vivid impressions to young minds. Muhlenberg was neither particularly romantic nor conservative or reactionary. Although several of Muhlenberg's former students and followers became Anglo-Catholics, he was dismayed when Newman converted to Roman Catholicism in 1845. Unthreatened by Darwinism, Muhlenberg was interested in modern ideas. He wrote patriotic poems and was the first Episcopal priest to hold a weekly Eucharist and daily offices. In 1853, he submitted a resolution to the General Convention of the Episcopal Church which became known as the Muhlenberg Memorial. The resolution calling for open-mindedness and the freedom of parish clergy to be responsive to parishioner needs, especially concerning Sunday-morning worship.[16] Some of Muhlenberg's papers and articles were published in two volumes from 1875 to 1877 as Evangelical Catholic Papers by Anne Ayres, who also wrote his official biography from papers he saved for her (she honored his request and destroyed most of his papers after his death). Later years In 1845, Muhlenberg moved to New York City. The following year he became rector of the Church of the Holy Communion, a rent-free church built by his sister Mary A. Rogers.[1] Muhlenberg founded the first American order of Protestant Episcopal deaconesses, the Sisterhood of the Church of the Holy Communion, between 1845 and 1852. His work with the sisterhood led to the 1850 establishment of St. Luke's Hospital, for which his congregation made offerings each St. Luke's Day beginning in 1847. In 1866, Muhlenberg founded the Church Industrial Community of St. Johnland on Long Island. He bought 535 acres (217 ha) with 1.5 miles (2.4 km) of shorefront on Long Island Sound near Kings Park as a home for young, crippled children and the elderly. A moderate rent was charged for the cottages. Muhlenberg died on April 8, 1877, in St. Luke's Hospital, and is buried in the St. Johnland cemetery.[2] Muhlenberg is honored with a feast day on the liturgical calendar of the U.S. Episcopal Church on April 8, his death day.[17] His reputation as an educator has been partially overshadowed by his extracurricular achievements after his move to New York City. See also

References

Further reading

External linksWikimedia Commons has media related to William Augustus Muhlenberg. Wikiquote has quotations related to William Augustus Muhlenberg.

|

||||||||||||||||