|

Western stereotype of the male ballet dancer

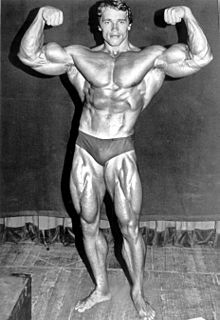

Since the early 19th century, the Western world has adopted a view of male ballet dancers, or danseurs as weak, effeminate or homosexual. Through gender expectations and performance, male ballet dancers combat the stereotypes that surround them.[1][2] Through education and media exposure, the stereotypes about male ballet dancers[clarification needed] lead to changes in perception.[3][1] The start of male ballet dancers Ballet was started in Italian and French courts during the fifteenth century.[3] During this time graceful and delicate characteristics were a sign of power.[4] Many noblemen started dancing ballet to demonstrate their position in society.[4] Louis XIV of France founded the Académie Royale de Danse.[3] It was the first ballet school. Men were considered the stars of ballet until the nineteenth century, when women were pushed into more of the spot light.[3] A couple of different factors influenced this shift. First, audience members changed when ballet moved from taking place in palaces to stages.[4] Second, there was a cultural shift that created more ethereal themes.[3] Response of male dancers William L. Earl's 1988 exploration of American stereotypes asked upper-middle class mall shoppers to describe male ballet dancers, as a whole, using up to 15 words or phrases. The most common responses were: "Pretty boys afraid to soil themselves with honest labor", "Snobs!", "secretive", "neurotic", "narcissistic", "soft", "vain", "frail", "homosexual", "Momma's Boy", “irresponsible", "probably hard workers", "creatures of the night", "flighty", "afraid of intimacy", "use people", "cold", and "fancy".[5] In a 2003 sociological study, male ballet dancers reported several stereotypes they had been confronted with, including "feminine, homosexual, wimp, spoiled, gay, dainty, fragile, weak, fluffy, woosy, prissy, artsy and sissy".[6] In preparation for their 2009 anthology on masculinity and dance, Jennifer Fisher and Anthony Shay interviewed several male dancers from different age groups, ethnic backgrounds, and sexualities. In the interviews, the men were asked questions pertaining to the biased picture of male dancers such as "Do you think you're now surrounded by any stereotypes about men and dancing?" and "Are there perceptions about men who dance that you think need changing?"[7] One of the dancers interviewed, Aaron Cota, came up against unfair prejudices but helped dispel them. He took some time off to enter the Marine Corps. He tells of his fellow Marines' reaction: "When they found out that [I would be earning a] dance degree, they were like 'What? You're what?'. They were kind of confused. You just have to explain it to them. When the guys in my unit would see some of the things I've done, or they see videos of other people dance, and they're like, 'Holy crap, how can they do that?' ... and they're like 'Wow, that's amazing,' and 'That's kind of opened my eyes ...'".[8] Another dancer, David Allan, experienced very negative effects of the stereotype growing up. He tells of the time he performed in his school's talent show at age eleven, "I was so excited about doing A Dance from David, my first choreography. So, when I came out in my pretty white tights, there was a big roar of laughter.... Later I met some guys in the hallway of my school who were making rude comments ... 'You're that dancer guy' would turn into being thrown down the stairs."[9] A number of notable actors, sportsmen and other celebrities have studied ballet, including Australian rules footballers James Hird and Josh Dunkley,[10][11][12] footballer Rio Ferdinand, rap artist Tupac Shakur, and actors Arnold Schwarzenegger, Christian Bale, Jamie Bell and Jean-Claude Van Damme, noted for their action and martial arts acting roles.[13] Gender expectations and performance Male ballet dancers are often disdained because of the belief that ballet is a feminine activity.[1] There are a couple of ways that male ballet dancers combat this idea. Male ballet dancers take on different movement characteristics and different technique compared to their female counter parts.[1][2] Men are expected to have movement that is strong and powerful. They are also expected to be good solid bases that can lift a person.[2] Within the dance world words like strong, proud, and in control were used to describe a good male ballet dancer.[2] A good female dancer was described as timid, modest, and light.[2] Male ballet dancers perform more athletic technique.[2] Men focus more on leaps and jumps and are expected to get more height and power in their technique.[2] Within the dance world there is a strong push for male ballet dancers to have masculine characteristics. They are often told to dance like a man from a young age. Male dancers that have feminine movement qualities are usually looked down on.[1] They are often described as weak, fragile, and out of place.[2] Reasons for negative responseThese negative responses to men in the dance world come from the lack of association of male stereotype to the stereotypes of dance. Men are often perceived as and are expected to display qualities such as dominance, independence, authority, strength, and a lack of emotions. Female stereotypes, on the other hand, include submissiveness, dependence, compliance, vulnerability, and emotion. Stereotypes of dance are linked closer to female stereotypes as dance is an expression of emotion.[14] In ballet, one must be vulnerable to the people around them, whether it's to trust others to lift, catch, or move in a synchronized manner. Men and masculinity correlate and are oftentimes indistinguishable from one another. Masculinity in itself is a social standing that associates with certain roles and practices. Masculinity creates a symbolic meaning of what it means to be a man, which involve many stereotypical male qualities. As a social standing, masculinity is pressured on men by society, and if unfulfilled, society freely ridicules and ostracizes men for their failure to effectuate its symbolic meaning.[15] Since dance is an expression of emotion that is based on vulnerability, men thus open themselves to mockery by displaying different characteristics than the expected male attributes. Effect on participationIn a study done on peer attitudes of participants in "gender specific" sports (e.g. ballet and American football), teens ages 14–18 were found to have strong stereotypical views. Males who frequently participated in a "sex-inappropriate" athletic activity were perceived as more feminine than those who did not. The study also suggested, "This stereotyping of athletes may have an important impact on the willingness of athletes to participate in certain sports. Likewise, these stereotypes may tend to filter out certain types of potential participants — e.g., macho males ... in athletic activities which are 'inappropriate' for one's gender."[16] Victoria Morgan, a former principal ballerina with the San Francisco Ballet now an Artistic Director and C.E.O. of the Cincinnati Ballet, relates "... I feel there is a stigma attached to ballet in America that doesn't reflect the reality.... This makes it difficult to attract some audience members and boys for ballet companies".[17] Changing the perspectiveOne strategy used to combat the stereotypical attitudes is to discuss the social constructs of gender within dance education. There have also been programs like “Boys Dancing” that oppose the idea that boys should not dance.[1] Media can also help change the perspective on male ballet dancers. After the movie Billy Elliot released in 2000, in dance classes there was a dramatic increase in male enrollment. For example, more boys than girls were admitted in the Royal Ballet School which had never been done before.[3] Reality shows like Dancing with the Stars and So You Think You Can Dance have also impacted enrollment rates in a positive way.[3] Many students credit these shows as the spark to start dancing and study ballet.[3] Ballet has been increasingly utilised by Australian Football League players to help rehabilitate from injuries, particularly leg and foot injuries, with examples of players to do so including Harley Bennell, Ben Reid, Sam Wright, Ben Jacobs and Brett Deledio.[18] Appearances in media

Citations

References

|