|

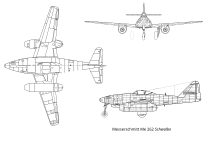

Weingut I 48°14′25.42″N 12°27′9.57″E / 48.2403944°N 12.4526583°E Weingut I (English: Vineyard I) was the codename for a construction project, begun in 1944, to create an underground factory complex in the Mühldorfer Hart forest, near Mühldorf am Inn in Upper Bavaria, Germany. Plans for the bunker called for a massive reinforced concrete barrel vault composed of 12 arch sections under which Messerschmitt Me 262 jet engines would be manufactured in a nine-storey factory. Upon completion these were to be sent to a similar installation in the area of Landsberg am Lech (codename Weingut II), where the final assembly of the aircraft was to take place. This network of underground factories was intended to ensure the production of the Me 262 at a time when the Allies had already gained control of the German airspace.[1] Despite it being increasingly clear to the organizers of the project that it would never be finished in time to make a difference in the war,[2] the construction of Weingut I was approved on a 6-month timeline. Of a total of 10,000 workers who worked on the project, 8,500 were forced laborers and inmates of the Mühldorf concentration camp network. Of these more than 3,000 died of overwork, underfeeding, and SS brutality.[3] By the war's end, only 7 of the planned total of 12 bunker sections had been built, and construction of the factory itself had not begun. After the liberation of the area and its associated camps in May 1945, control of the construction site fell to the US Army, which made extensive studies of its innovative construction techniques before demolishing all but one section of the main bunker in 1947. Today the bunker grounds are a listed monument. Occasional tours of the site are offered by a Catholic nonprofit group in Mühldorf. Background In early 1944, the Allied air war began to focus primarily upon the destruction of the Luftwaffe in preparation for the invasion of Normandy. Plans for the so-called "Big Week", which was intended to permanently smash the German capacity to produce fighter aircraft through targeted airstrikes on final assembly factories, were already underway in 1943. Between February 20–25, 1944, approximately 10,000 American and British aircraft, including about 6,000 bombers, attacked strategic targets all over Germany. Following these attacks, which seriously damaged German aircraft production, the production quota fell drastically. In response the Jägerstab (Fighter Staff) was founded in March 1944 with the task of ensuring the preservation and growth of fighter aircraft production. It superseded the Ministry of Aviation in this jurisdiction. At the head of the Jägerstab was armaments minister Albert Speer, as Deputy the Secretary of State Erhard Milch, as Chief of Staff Karl Saur. Their plan to protect the aircraft industry, especially the manufacture of the jet-powered Messerschmitt Me 262, entailed the relocation of assembly plants into underground bunkers. This idea was not entirely new, as a similar (but never realized) proposal had already been considered in October 1943.[4] The Jägerstab's plan included six locations in which partially underground bunkers were to be built, and at first called for the bunkers to be encompass a minimum area of 600,000 to 800,000 m2 apiece.[5] However, by the time of the Jägerstab meeting of 17 March 1944, the projected size of the each building had sunk to 60,000 m2.[6] By June 1944 the invasion of the allies had forced the Jägerstab to focus in the end on two locations in Upper Bavaria. Three bunkers were to be built at Kaufering in the Landsberg am Lech district under the codename "Ringeltaube" (common wood pigeon), while the codename "Weingut I" (Vineyard I) was chosen for the factory in the Mühldorfer Hart. According to the testimony of Franz Xaver Dorsch, who was responsible for the construction, the fighter factory would be completed in five to six months at best.[7] Speer later wrote in his memoirs that at the time it was already not difficult to foresee that the project would not be completed within the planned time.[2][8] The location in the area of Mühldorf fulfilled all of the important requirements. There was an adequately solid gravel bed beneath the terrace of the Inn and the water table was adequately deep. Strategically the important railway juncture of Mühldorf was advantageous, and the wide-ranging forest of the Mühldorfer Hart would offer excellent camouflage for the completed bunker.[1] ConstructionManagementThe chief construction office of Organisation Todt (OT) in Berlin, and therefore Speer's deputy in the OT Franz Xaver Dorsch, was responsible for the planning and organization of the project.[9] On site the "OT-Einsatzgruppe Deutschland VI" (OT-Task Force Germany VI) supervised the construction from their offices in Ampfing, Mettenheim and Ecksberg at Mühldorf. Architect Bruno Hofmann was the "OT Oberbauleiter" (Chief Construction Leader). The technical aspects of the construction were assigned to the company Polensky & Zöllner (P & Z). Other companies worked on the project as subcontractors. P & Z had already been active in the area of Mühldorf in the 1920s, with the building of the Inn Canal. Almost 200 employees of the company were sent to Mühldorf for the project, where they operated as the OT unit Polensky & Zöllner, Bautrupp 773. The P & Z leader at the construction site was the engineer Karl Gickeleiter. The cost of the project has been estimated at almost 26 million Reichsmarks (equivalent to 105 million 2021 €).[10][11] Workforce A huge workforce was necessary for the construction project. P & Z used a total of 200 of its own workers, about 800 to 1000 workers from their affiliated Soviet companies, and 200 to 300 Italian workers.[12] This group of about 1,500 was vastly inadequate if the project was to be completed on schedule. Therefore, it was decided that forced labor would be employed, as was common under the Nazis for projects of this magnitude. A large portion of the forced workers were prisoners of the Mühldorf concentration camp. Further labor camps were built by the OT to house them in the Mühldorfer Hart, Ampfing, Mettenheim and Ecksberg. A large number of Soviet prisoners of war also made up the forced laborers. Overall more than 10,000 workers were assigned to the Weingut I construction site.[10] As a rule, two shifts of 4,000 men apiece worked on the project. According to the records of P & Z the POWs worked a total of 322,513 hours; the concentration camp prisoners, 2,831,974. The company was paid 1,892,656.20 Reichsmarks by the SS and the OT.[13] PreparationsAdolf Hitler's orders of 21 April 1944[9] gave official approval for the commencement of work on the structure. Next the necessary ground for the project was confiscated without compensation. Around the middle of May the OT established its offices in the Ecksberg Foundation's (Stiftung Ecksberg) building complex. The Ecksberg Foundation, a home for the mentally ill, had been taken over by the state in 1938. It was uninhabited by this time, as the Nazis had soon thereafter murdered some 248 to 342 of those in the foundation's care as part of the Action T4 program.[14] At the same time the OT erected its first barracks camp. Afterward the required construction machinery was little by little supplied to Mühldorf. The equipment had to be brought together from sources throughout the Reich and its occupied territories, which was an especially complicated endeavor given the military situation.[15] Nonetheless a concrete factory, a carpentry shop, a gravel sorting plant and further facilities had to be built. Besides these additional smaller bunkers intended to serve as air raid shelters were erected before construction on the main site began.[16] For the transportation of material to and from the site the Reichsbahn laid down a network of siding that was connected to the Munich-Mühldorf line.[17] Upon completion the entire bunker was to be covered with soil and planted over with trees and bushes, but considering the scale of the project it was hardly possible to effectively camouflage it from aerial reconnaissance during the construction process. Efforts to that effect were therefore not especially thorough. Indeed, the site was hard to miss, and the USAF took several aerial photos of it in February 1945 during reconnaissance prior to the bombardment of the airfield at Mettenheim and the train yard at Mühldorf. The site was discovered upon examination of the photos, as an overhead view of main bunker drawn in March 1945 and labeled "MUHLDORF (GERMANY) SEMI-BURIED INSTALLATION" attests.[18] The site was never bombed, however. The reasons why are unclear. One reason could be that the existence of the work camp was known and that the Allies did not want to risk bombing it by accident. It may also have been known that its completion was unlikely and thus other targets presented a higher priority.[19] Process The actual work on Weingut I began in July 1944. According to plans, the bunker would be made up of 12 arches stretching east to west in a barrel vault 400 meters long and 85 meters wide. The arches would have an internal height of 32.2 m, of which 19.2 m was under the ground level. Their thickness reached 3 meters, and would have eventually reached 5 meters through a further concrete pour.[20] For the building of the bunker an effective and simple new procedure was employed. First an underground "extraction tunnel", fitted with a single train track and a gated roof, was built along the entire length of the planned bunker. Next the foundations for the abutments, which were up to 17 m thick, were dug. The gravel extracted from the foundations was piled up between the foundations to support the arches while they were being built, essentially serving as formwork instead of traditional wooden scaffolding. As each arch was completed, the gravel beneath it was dug out and dumped through the gates of the extraction tunnel into waiting mine carts, which would then be taken away. When the tunnel had been completely uncovered it would be disassembled and backhoes would continue the excavation to a depth of 19.2 meters. Starting from the east, one arch after another was erected in this way. Eight floors were to be erected beneath the arches, but this was only begun with the first arch. By the end of April 1945 only seven of the projected twelve arches were completed. In the last months of the war it was no longer possible to obtain the necessary materials and workers in order to stay on schedule.[21] War's end and afterwardCapture and demolition When the 47th tank battalion of the 14th Armored Division reached Mühldorf in the early days of May 1945, the construction area and all related facilities were placed under US military administration. The company was allowed to dismantle and remove its construction equipment, and the Reichsbahn took up the tracks that led to the complex. Next the army decided to use the grounds as a bomb test site in order to determine the effectiveness of the bunker:[22]

This proposal was accepted and in the summer of 1947 the command for the demolition was issued. 125 tonnes of TNT were used for the demolition, which destroyed six of the seven completed arches and damaged the seventh.  TrialAfter the war the US Army's Dachau Military Tribunal prosecuted perpetrators of war crimes in connection with the Weingut I project and the associated concentration and labor camps in the Mühldorf Trial, which was one of the Dachau Trials. Among the accused were members of Polensky & Zöllner's administration, including Karl Bachmann, Director of the Munich branch of P & Z; Karl Gickeleiter, who oversaw construction at the main site; and Otto Sperling, construction foreman. The sentencing was performed on 13 May 1947. The charges against Karl Bachmann were dropped, as his involvement in the maltreatment of the prisoners could not be proven. Gickeleiter was sentenced to a 20-year prison term, which would be reduced to 10 years in 1951 before he was released early on 19 July 1952. The death sentence against Sperling was shortly thereafter shortened to life imprisonment and later reduced even further before he was finally released on 20 July 1957.[24] 1980s to todayThe ruins of the bunker complex can still be seen in the woods near Mettenheim, although much material from the site has been scavenged in the intervening years by local companies for other building projects. The grounds entered the public eye again in the 1980s, when rumors began to circulate that chemical agents of the Wehrmacht had been stored in the tunnels of the complex after the war. This was not confirmed by the authorities until 1987; the chemicals, including CLARK 2, were subsequently removed.[25] In 1992, the Bundesvermögensverwaltung (Federal Property Administration, an agency that has since been superseded by the Bundesanstalt für Immobilienaufgaben) proposed to demolish the bunker. Although the communities of Mettenheim and Ampfing endorsed the demolition, many others opposed the proposal, and it was rejected by the government of Upper Bavaria.[26] In the meantime the bunker grounds had been added to the Bavarian list of monuments as a memorial to the victims of Nazi atrocities.[27] Today the Mühldorf District Catholic Education Center (Katholische Kreisbildungswerk Mühldorf) administers occasional tours of the bunker grounds and the former concentration camp.[28] Gallery

See also

Citations

ReferencesIn German

In English

External linksWikimedia Commons has media related to U-Verlagerung Weingut I. |