|

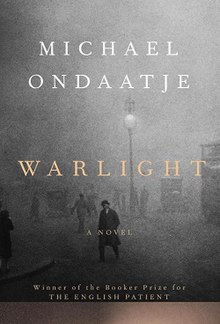

Warlight

Warlight is a 2018 novel by Canadian author Michael Ondaatje. In London near the end of World War II, 14-year-old Nathaniel and his sister Rachel are left in the care of an enigmatic figure named The Moth, their parents having moved to Singapore.[1][2] The Moth affiliates with a motley group of eccentric, mysterious, and in some ways nefarious characters who dominate the children's experience early in the postwar period.[2] SynopsisIn 1945 at the end of the war, Nathaniel's father and mother decide to leave London for a year to go to Singapore, where Nathaniel's father is being stationed. The parents decide to leave their children, 14-year-old Nathaniel and his older sister Rachel, in the care of their lodger, Walter, known as The Moth. The children both have the impression that The Moth is a thief. Nathaniel's mother claims to know The Moth because they were both in charge of fire watching at the Grosvenor House Hotel during the war but their stories about the war imply that they had other, secretive war jobs. Nathaniel and Rachel are supposed to be boarders at their school when their parents leave, but after complaining to The Moth they are allowed to live at their home which is now populated by an odd mix of characters. One of these is The Moth's friend, The Darter, who imports greyhounds into England for the purpose of illegal gambling and ferries explosives by barge from Waltham Abbey Royal Gunpowder Mills into central London. The Darter helps Nathaniel gain employment, first at a restaurant where he meets a working-class girl, Agnes Street, who he develops a relationship with, and later employing him to aid in smuggling. When Agnes thinks that Nathaniel does not want to introduce her to his parents because he is ashamed of her, Nathaniel has The Darter pretend to be his father. The Darter similarly helps Rachel, who develops epilepsy during this time period, by teaching Nathaniel how to deal with the symptoms, and helping Rachel find employment in a theatre. After the year has elapsed and his parents have still not returned, Nathaniel begins to suspect he is being followed, and also that his mother is still somewhere in England, possibly also in London. One night while out with Rachel and The Moth, all three are attacked by men who have been following Nathaniel for some time. When Nathaniel awakens, he and Rachel have already been rescued. He is also able to see his mother, briefly, who implies that giving up the children was part of a deal she made to ensure their safety. Shortly thereafter, Nathaniel and Rachel are separated and re-homed, with Rachel going to boarding school in the country, and Nathaniel briefly attending a boarding school in America. In 1959 Nathaniel, now an adult, is recruited by the Foreign Office to help in a mass censorship of post-WWII espionage activities, the censorship being known as The Silent Correction. Nathaniel buys a home in The Saints where his mother grew up and where he briefly lived with her after his return from America. Nathaniel also tries to connect with members of his past but The Moth is dead after their attack and almost everyone else has scattered. He and Rachel have a tense relationship though he eventually learns he has a nephew, named Walter after The Moth. Nathaniel's personal reason for accepting his Foreign Office work is to look for traces of his mother. Though he is never handed any documents that refer to her, Nathaniel begins breaking into the office and temporarily stealing files to try to learn more about her and her activities. He realises that one of the much higher up employees also attended his mother's funeral and that he is also a man named Marsh Felon, who his mother knew when they were both children and Felon's family worked for hers. Through a few sparse details from the files and in recollecting information given to him by his mother in the brief time they lived together in The Saints, Nathaniel tries to trace his mother's war work and her relationship with Felon and imagines that they were both friends and lovers. They had worked with partisans in Yugoslavia and it is the daughter of a victim of the partisans in the Foibe massacres who tracks down and kills his mother. Nathaniel also discovers that some of The Darter's so-called illicit activities were done in service to the war and post-war efforts. While digging in the archives he finds The Darter's real name, Norman Marshall, and a current address and goes to visit him. He is surprised to find The Darter married with a daughter though he does not meet either of them. Upon leaving he sees a piece of embroidery with a quote that Agnes loved and he realises that The Darter is married to Agnes and their child was likely fathered by Nathaniel. Despite entertaining a fantasy that he will one day run into his daughter, Nathaniel continues to live his mostly solitary life leaving Agnes and her family undisturbed. Characters

InterpretationPenelope Lively wrote in The New York Times that the "signature theme" of the novel is that "the past never remains in the past", its "paramount subject matter" being that "the present reconstructs the past".[2] As the title's term 'warlight' is thought to refer, literally, to the blackouts of World War II, Lively wrote that the novel's narrative is likewise "devious and opaque" and proceeds "by way of hints and revelations", that its characters are elusive and evasive, and that the novel has an "intricate and clever construction" requiring a close reading.[2] As background, Alex Preston wrote in The Guardian that much of Ondaatje's literary career has been driven by the perception that "memory is the construct of the older self looking back".[3] Calling Ondaatje "a memory artist", Preston wrote that the author "summons images with an acuity that makes the reader experience them with the force of something familiar, intimate and truthful".[3]

Nathaniel Williams,

narrator in Warlight [4] A.S.H. Smyth wrote in The Spectator that Ondaatje is "at his best when writing about awkward, quiet types, and 'those at a precarious tilt', and characters, especially narrators, with dodgy memories", Smyth noting that the novel's narrator Nathaniel said that he "knows how to fill in a story from a grain of sand".[5] Writing in The New Republic, Andrew Lanham noted the significance of Nathaniel's postwar job working for British Intelligence as a historian reviewing after-action reports, Lanham implying that the novel articulated the "need to probe the archives for what really happened: In our cultural memory of the wars of the past, only the rereading counts".[6] In this context, Lanham wrote that Ondaatje's literary career has echoed Nathaniel's task, with several of Ondaatje's novels "circling around war and the challenge of remembering and recovering from war".[6] On August 19, 2018, former U.S. President Barack Obama included Warlight in his summer reading list, describing the novel as "a meditation on the lingering effects of war on family".[7] Critical response and reviewsWarlight reached The New York Times Best Seller list within the month of its publication.[8] In July 2018 Warlight was longlisted among thirteen novels for the Man Booker Prize.[9] Penelope Lively wrote in The New York Times that Warlight is rich with detail, having meticulous background research that brings alive a time and a place, Lively summarizing the novel as "intricate and absorbing".[2] Similarly, Robert Douglas-Fairhurst wrote in The Times that most of the novel's movements are "measured and catlike" with "writing that is prepared to take its time", concluding that Warlight is a novel of "shadowy brilliance".[10] Anthony Domestico wrote in The Boston Globe that "Ondaatje's is an aesthetic of the fragment", his novels "constructed, with intricate beauty, from images and scenes that don't so much flow together as cling together in vibrating, tensile fashion. ... built more from juxtaposition and apposition than from clean narrative progression".[4] Likewise crediting Warlight as "a series of sharply perceived images", Alex Preston wrote in The Guardian that the novel "sucked me in deeper than any novel I can remember; when I looked up from it, I was surprised to find the 21st century still going on about me."[3] Indicating that Warlight would not disappoint "lovers of intrigue, betrayal, war-torn cities and score-settling", A.S.H. Smyth described in The Spectator how the novel did not glorify war and concluded that "it's hard not to think of Warlight as an adroit and unromantic B-side to (Ondaatje's 1992 novel) The English Patient.[5] References

External links

|

||||||||||||||||||||