|

Vulvar cancer

Vulvar cancer is a cancer of the vulva, the outer portion of the female genitals.[1] It most commonly affects the labia majora.[1] Less often, the labia minora, clitoris, or Bartholin's glands are affected.[1] Symptoms include a lump, itchiness, changes in the skin, or bleeding from the vulva.[1] Risk factors include vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia (VIN), HPV infection, genital warts, smoking, and many sexual partners.[1][3] Most vulvar cancers are squamous cell cancers.[4] Other types include adenocarcinoma, melanoma, sarcoma, and basal cell carcinoma.[3] Diagnosis is suspected based on physical examination and confirmed by tissue biopsy.[1] Routine screening is not recommended.[3] Prevention may include HPV vaccination.[5] Standard treatments may include surgery, radiation therapy, chemotherapy, and biologic therapy.[1] Vulvar cancer newly affected about 44,200 people and resulted in 15,200 deaths globally in 2018.[6] In the United States, it newly occurred in about 6,070 people with 1,280 deaths a year.[2] Onset is typically after the age of 45.[2] The five-year survival rate for vulvar cancer is around 71% as of 2015.[2] Outcomes, however, are affected by whether spread has occurred to lymph nodes.[4] Signs and symptoms The signs and symptoms can include:

Typically, a lesion presents in the form of a lump or ulcer on the labia majora and may be associated with itching, irritation, local bleeding or discharge, in addition to pain with urination or pain during sexual intercourse.[8] The labia minora, clitoris, perineum and mons pubis are less commonly involved.[9] Due to modesty or embarrassment, people may put off seeing a doctor.[10] Melanomas tend to display the typical asymmetry, uneven borders and dark discoloration as do melanomas in other parts of the body. Adenocarcinoma can arise from the Bartholin's gland and present with a painful lump.[11] CausesTwo main pathophysiological pathways are currently understood to contribute to development of vulvar cancer—human papillomavirus (HPV) infection and chronic inflammation or autoimmunity affecting the vulvar area.[12][13][14] HPV DNA can be found in up to 87% of vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia (VIN) and 29% of invasive vulvar cancers; HPV 16 is the most commonly detected subtype in VIN and vulvar cancer, followed by HPV 33 and HPV 18.[15] VIN is a superficial lesion of the skin that has not invaded the basement membrane—or a pre-cancer.[16] VIN may progress to carcinoma in situ and, eventually, squamous cell cancer. Chronic inflammatory conditions of the vulva that may be precursors to vulvar cancer include lichen sclerosus, which can predispose to differentiated VIN.[17][18] Risk factorsRisk factors for vulvar cancer are largely related to the causal pathways above, involving exposure or infection with the HPV virus and/or acquired or innate auto-immunity.[19][20]

DiagnosisExamination of the vulva is part of the gynecologic evaluation and should include a thorough inspection of the perineum, including areas around the clitoris and urethra, and palpation of the Bartholin's glands.[21] The exam may reveal an ulceration, lump or mass in the vulvar region. Any suspicious lesions need to be sampled, or biopsied. This can generally be done in an office setting under local anesthesia. Small lesions can be removed under local anesthesia as well. Additional evaluation may include a chest X-ray, an intravenous pyelogram, cystoscopy or proctoscopy, as well as blood counts and metabolic assessment. TypesDepending on the cellular origin, different histologic cancer subtypes may arise in vulvar structures.[22][23] Squamous cell carcinomaA recent analysis of the Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) registry of the US National Cancer Institute has shown that squamous cell carcinoma accounts for approximately 75% of all vulvar cancers.[22] These lesions originate from epidermal squamous cells, the most common type of skin cell. Carcinoma-in-situ is a precursor lesion of squamous cell cancer that does not invade through the basement membrane. There are two types of precursor lesions:

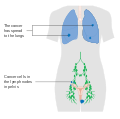

Squamous lesions tend to arise in a single site and occur most commonly in the vestibule.[24] They grow by local extension and spread via the local lymph system. The lymphatics of the labia drain to the upper vulva and mons pubis, then to both superficial and deep inguinal and femoral lymph nodes. The last deep femoral node is called the Cloquet's node.[24] Spread beyond this node reaches the lymph nodes of the pelvis. The tumor may also invade nearby organs such as the vagina, urethra, and rectum and spread via their lymphatics. A verrucous carcinoma of the vulva is a rare subtype of squamous cell cancer and tends to appear as a slowly growing wart. Verrucous vulvar cancers tend to have a good overall prognosis, as these lesions hardly ever spread to regional lymph nodes or metastasize.[22][25] Basal cell carcinomaBasal cell carcinoma account for approximately 8% of all vulvar cancers. It typically affects women in the 7th and 8th decade of life.[22] These tend to be slow-growing lesions on the labia majora but can occur anywhere on the vulva. Their behavior is similar to basal cell cancers in other locations. They often grow locally and have low risk for deep invasion or metastasis. Treatment involves local excision, but these lesions have a tendency to recur if not completely removed. MelanomaMelanoma is the third most common type and accounts for 6% of all vulvar cancers.[22] These lesions arise from melanocytes, the cells that give skin color. The median age at diagnosis is 68 years; however, an analysis of the Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) registry of the US National Cancer Institute has shown that it has been diagnosed in girls as young as 10 years and women up to 107 years.[22][26] The underlying biology of vulvar melanoma differs significantly from skin melanomas and mutational analyses have shown only 8% harbor a BRAF mutation compared to 70% of skin melanomas.[27] KIT mutations, however are significantly more common in vulvar melanoma.[22][27] This has a direct impact on the medical treatment of vulvar melanomas: BRAF-inhibitors that are commonly used in the treatment of skin melanomas, play a minor role in vulvar melanomas. However, vulvar melanomas frequently express PD-L1 and checkpoint inhibitors (including CTLA-4 inhibitors and PD-1 inhibitors) are effective in the treatment of advanced-stage vulvar melanoma.[28] In recurrent melanoma, tyrosine kinase inhibitors may be used in those patients with a KIT mutation.[22][27] Based on histology, there are different subtypes of vulvar melanoma: superficial spreading, nodular, acral lentigous and amelanotic melanoma. Vulvar melanomas are unique in that they are staged using the AJCC cancer staging for melanoma instead of the FIGO staging system.[29] Diagnosis of vulvar melanoma is often delayed and approximately 32% of women already have regional lymph node involvement or distant metastases at the time of diagnosis.[24][29] Lymph node metastases and high mitotic count are indicators of poor outcome.[29] The overall prognosis is poor and significantly worse than in skin melanomas: The median overall survival is 53 months.[29][28] Bartholin gland carcinomaThe Bartholin gland is a rare malignancy and usually occurs in women in their mid-sixties. Other lesionsOther forms of vulvar cancer include invasive Extramammary Paget's disease, adenocarcinoma (of the Bartholin glands, for example) and sarcoma.[22][30] StagingAnatomical staging supplemented preclinical staging starting in 1988. FIGO's revised TNM classification system uses tumor size (T), lymph node involvement (N) and presence or absence of metastasis (M) as criteria for staging. Stages I and II describe the early stages of vulvar cancer that still appear to be confined to the site of origin. Stage III cancers include greater disease extension to neighboring tissues and inguinal lymph nodes on one side. Stage IV indicates metastatic disease to inguinal nodes on both sides or distant metastases.[31]

Differential diagnosisOther cancerous lesions in the differential diagnosis include Paget's disease of the vulva and vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia (VIN). Non-cancerous vulvar diseases include lichen sclerosus, squamous cell hyperplasia, and vulvar vestibulitis. A number of diseases cause infectious lesions including herpes genitalis, human papillomavirus, syphilis, chancroid, granuloma inguinale, and lymphogranuloma venereum. Treatment Surgery is a mainstay of therapy depending on anatomical staging and is usually reserved for cancers that have not spread beyond the vulva.[31] Surgery may involve a wide local excision (excision of the tumor with a safety-margin of healthy tissue, that ensures complete removal of the tumor), radical partial vulvectomy, or radical complete vulvectomy with removal of vulvar tissue, inguinal and femoral lymph nodes.[22][26] In cases of early vulvar cancer, the surgery may be less extensive and consist of wide excision or a simple vulvectomy. Surgery is significantly more extensive when the cancer has spread to nearby organs such as the urethra, vagina, or rectum. Complications of surgery include wound infection, sexual dysfunction, edema and thrombosis, as well as lymphedema secondary to dissected lymph nodes.[33] Sentinel lymph node (SLN) dissection is the identification of the main lymph node(s) draining the tumor, with the aim of removing as few nodes as possible, decreasing the risk of adverse effects. Location of the sentinel node(s) may require the use of technetium(99m)-labeled nano-colloid, or a combination of technetium and 1% isosulfan blue dye, wherein the combination may reduce the number of women with "'missed"' groin node metastases compared with technetium only.[33] Radiation therapy may be used in more advanced vulvar cancer cases when disease has spread to the lymph nodes and/or pelvis. It may be performed before or after surgery. In early vulvar cancer, primary radiotherapy to the groin results in less morbidity but may be linked with a higher risk of groin recurrence and reduced survival compared to surgery.[34] Chemotherapy is not usually used as primary treatment but may be used in advanced cases with spread to the bones, liver or lungs. It may also be given at a lower dose together with radiation therapy.[35] Checkpoint inhibitors may be given in melanoma of the vulva.[28] There is no significant difference in overall survival or treatment‐related adverse effects in women with locally advanced vulval cancer when comparing primary chemoradiation or neoadjuvant chemoradiation with primary surgery. There is a need for good quality studies comparing various primary treatments.[36] Women with vulvar cancer should have routine follow-up and exams with their oncologist, often every three months for the first 2–3 years after treatment. They should not have routine surveillance imaging to monitor the cancer unless new symptoms appear or tumor markers begin rising.[37] Imaging without these indications is discouraged because it is unlikely to detect a recurrence or improve survival and is associated with its own side effects and financial costs.[37] PrognosisOverall, five-year survival rates for vulvar cancer are around 78%[24] but may be affected by individual factors including cancer stage, cancer type, patient age and general medical health. Five-year survival is greater than 90% for patients with stage I lesions but decreases to 20% when pelvic lymph nodes are involved. Lymph node involvement is the most important predictor of prognosis.[38] Prognosis depends on the stage of cancer, which refers the amount and spread of cancer in the body.[39] The stages are broken into four categories. Stage one also called "localized" and is when the cancer is limited to one part of the body.[39] This has the highest survival rate of 59%.[39] When the cancer starts to spread this is referred to "distant" or "regional", this stage usually involves the cancer being spread to the lymph nodes.[39] This survival rate is 29%. The third stage is when the cancer has metastasized and spread throughout the body, this is the lowest survival rate of 6%. When vulvar cancer is caught early that is when the survival rate is at its highest.[39] EpidemiologyVulvar cancer newly affected about 44,200 people and resulted in 15,200 deaths globally in 2018.[6] Vulvar cancer can be split up into two types. One starts as an infection by human papillomavirus, which leads to vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia (VIN) and potentially on to vulvar cancer.[40] This is most common in younger women, predominantly under the age of 40.[40] The second type is vulvar non-neoplastic epithelial disorders (VNED). This is most common in older women, due to the increased risk for developing cellular atypia which in turn leads to cancer.[40] United KingdomVulvar cancer causes less than 1% of all cancer cases and deaths but around 6% of all gynecologic cancers diagnosed in the UK. Around 1,200 women were diagnosed with the disease in 2011, and 400 women died in 2012.[41] In the United Kingdom 7 out of 10 vulval cancer patients have major surgical resection as part of their cancer treatment.[42] 22% of patients use radiotherapy and only 7% use chemotherapy as a treatment plan.[42] There are very high survival rates, patients diagnosed with vulvar cancer have an 82% of living more than one year, a 64% chance of living at least five years and a 53% chance of living ten or more years.[42] The rate of survival increases dependent on age of patient and the stage the cancer was found in. United StatesIn the United States, it newly occurred in about 6,070 people with 1,280 deaths a year.[2] It makes up about 0.3% of new cancer cases,[2] and 5% of gynecologic cancers in the United States.[43] Vulvar cancer cases have been rising in the United States at an increase of 0.6% each year for the past ten years.[39] See alsoReferences

External links

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||