|

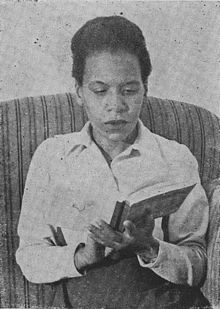

Virginia Brindis de Salas Virginia Brindis de Salas (18 September 1908 – 6 April 1958)[1] was an Uruguayan poet, Nuestra Raza collaborator, and social rights advocate through her written art. The country's leading Black woman poet, she is also considered "the most militant among Afro-Uruguayan writers".[2] Her poetry addresses the social reality of Black Uruguayans.[3] She published two collections of poetry during her lifetime, Pregón de Marimorena (The Call of Mary Morena) in 1946, and Cien cárceles de amor (One Hundred Prisons of Love) in 1949.Her writings made her, along with fellow Afro-Uruguayan Pilar Barrios, one of the few published Uruguayan women poets.[4] Early lifeVirginia Brindis de Salas was born in Montevideo,[1] Uruguay, the daughter of José Salas and María Blanca Rodríguez,[5] Little is known about her life; according to Joy Elizondo, she claimed to be the niece of Cuban violinist Claudio Brindis de Salas,[3] though this is unsubstantiated. CareerShe published two collections of poetry. The first, Pregón de Marimorena ("The Call of Mary Morena"), came out in 1946,[6] bringing her a certain amount of recognition. Chilean Nobel laureate Gabriela Mistral wrote of Brindis de Salas: "Sing, beloved Virginia, you are the only one of your race who represents Uruguay. Your poetry is known in Los Angeles and in the West. I have heard of your recent work through diplomatic friends, and, may God grant that this book be the key that opens coffers of luck to the only brave black Uruguayan woman that I know."[7] In 1949 Brindis de Salas issued Cien Cárceles de Amor ("One Hundred Prisons of Love"),[8] which is divided into four sections that each highlight a different type of African-derived music: "Ballads", "Calls", "Tangos" and "Songs".[3] Her poetry reflects upon the social and cultural realities of being Black in the Uruguay. Her poetry truthfully depicted the customs of her Black Uruguayan community, but also the inhuman social inequalities and racism they faced in Latin America. Brindis de Salas goal was to promote change in Uruguay by giving a voice to the silent minority. According to Caroll Mills Young, in both collections Brindis de Salas "poetically evokes the social and cultural reality of Afro-Uruguay.... The volumes are intended to promote social change in Uruguay; they exemplify the poet's crusade for solidarity, equality, and dignity."[9] In the prologue to Cien Cárceles de Amor Brindis de Salas mentioned a forthcoming third volume entitled Cantos de lejanía ("Songs from Faraway"), but this book was never published.[3] Brindis de Salas was also one of the founders and contributors to Nuestra Raza (Our Race), an Afro-Uruguayan journal published in Montevideo from 1917 to 1950. She also was apart of Circle of Black Intellectuals, Artists, Journalists, and Writers (CIAPEN), alongside other significant literary figures such as her counterpart Pilar Barrios, Juan Julio Arrascaeta, and Carlos Cardoso Ferreira. Advocating for racial and women rights beyond her poetry, Brindis de Salas also was co-founder of the political party Partido Autóctono Negro (PAN) founded in 1936. Known as the Black Native Party in English, they sought to defend the rights of the Black community in Uruguay and promote the election of Afro-Uruguayans in Congress.[10] Even though Virginia Brindis de Salas was bold through her poetry and actions as she promoted gender equality and social justice, this also resulted in her alienation from other Black-Uruguayan intellectuals. Instead of limiting herself to traditional themes of love and womanhood, she wrote from the "perspective of a black in a racist society." In contrast, other Black writers wanted to show the intellectuality of their Black-Uruguayan community rather than the negative realities they faced and Brindis de Salas wrote about. She has won critical acclaim for probing the lives of Black Uruguayan women and exposing their pain and suffering in the pages of her poetry. As the spokesperson for the voiceless, Brindis de Salas has represented Afro-Uruguay, and is presently considered the only Black female writer from the Southern Cone. [11] LegacyRecognitionWhile Brindis de Salas was an influential poet advocating for Afro-Uruguayans rights, her posthumous recognition is limited due to several factors including Uruguay's severe economic crisis, and the overshadowing of women writers during the 20th century. In the 1960's, after Brindis de Salas death in 1958, Uruguay dealt with high inflation and economic stagnation which also led to political tensions. Due to these countrywide challenges it is possible to assume Brindis de Salas and her proponents did not have the funds to publish her poem books. The devaluation of her work can also be attributed to the racial naivety and lack of union between Black intellectuals in Uruguay. A 1945 Nobel Prize winner, Gabriela Mistral, looked up to Brindis de Salas and advocated for her to be the authentic voice of Afro-Uruguay. Gabriela Mistral wrote to Virginia Brindis de Salas in 1949 while living in Los Angeles. She wrote to her and recommended that she come to the United States [12] Poetry's Impact on Uruguayan CommunityShe has won critical acclaim for writing about the lives of Black Uruguayan women and exposing their pain and suffering in the pages of her poetry. Since the publication of her piece, Pregón de Marimorena, Virginia Brindis de Salas has been the most studied Afro-Uruguayan woman writer abroad and in the United States.[13] There is something to be said about the fact that so many people study her pieces of work. WorksPregón de Marimorena (1946)Titled after one of the earliest forms of oral art in Uruguay, pregón symbolizes the enslavement of poor Black people. The collection of songs and poems tells the story of Marimorena, an impoverished Black woman trying to survive within the slums of Afro-Uruguay.[14] With the intention to be a defender for the poor, Brindis de Salas' poetry reflects the realities faced by Black individuals in the Southern Cone. [15] The poetic style used in this body of work is influenced by the folkloric and oral traditions and culture of Afro-Uruguay. Brindis de Salas' also liberates herself within her poetry by writing in free-verse. A second edition was published as well in 1952. Cien Cárceles de Amor (1949)In the prologue written by Isaura Bajac de Borjes, an Uruguayan author, Borjes compares Brindis de Salas' poems to laments, and mentions how she hopes her new book "opens the doors to liberation." Receiving high praise from various Latin American poets, Cien Cárceles de Amor criticizes the oppressor through her rebellious use of free-verse. Made up of twenty-three poems which each differ thematically, Cien Cárceles de Amor is a more personal rendition of the Black experience. Brindis de Salas' continues to emphasize the social and economic incarceration forced upon Afro-Uruguayan through her art.[16] References

Further reading

|