|

Variations and Fugue on a Theme by Handel

The Variations and Fugue on a Theme by Handel, Op. 24, is a work for solo piano written by Johannes Brahms in 1861. It consists of a set of twenty-five variations and a concluding fugue, all based on a theme from George Frideric Handel's Harpsichord Suite No. 1 in B♭ major, HWV 434. They are known as his Handel Variations. The music writer Donald Tovey has ranked it among "the half-dozen greatest sets of variations ever written".[1] Biographer Jan Swafford describes the Handel Variations as "perhaps the finest set of piano variations since Beethoven", adding, "Besides a masterful unfolding of ideas concluding with an exuberant fugue with a finish designed to bring down the house, the work is quintessentially Brahms in other ways: the filler of traditional forms with fresh energy and imagination; the historical eclectic able to start off with a gallant little tune of Handel's, Baroque ornaments and all, and integrate it seamlessly into his own voice, in a work of massive scope and dazzling variety."[2] The autograph manuscript of the work is preserved in the Library of Congress. BackgroundThe Handel Variations were written in September 1861 after Brahms, aged 28, abandoned the work he had been doing as director of the Hamburg women's choir (Frauenchor) and moved out of his family's cramped and shabby apartments in Hamburg to his own apartment in the quiet suburb of Hamm, initiating a highly productive period that produced "a series of early masterworks".[3] Written in a single stretch in September 1861,[4] the work is dedicated to a "beloved friend", Clara Schumann, widow of Robert Schumann. It was presented to her on her 42nd birthday, September 13. At about the same time, his interest in, and mastery of, the piano also shows in his writing two important piano quartets, in G minor and A major. Barely two months later, in November 1861, he produced his second set of Schumann Variations, Op. 23, for piano four hands. From his earliest years as a composer, the variation was a musical form of great interest to Brahms. Before the Handel Variations he had written a number of other sets of variations, as well as using variations in the slow movement of his Op. 1, the Piano Sonata in C major, and in other chamber works.[4] As he appeared on the scene, variations were in decline, "little more than a basis for writing paraphrases of favorite tunes".[4] In Brahms's work the form once again became restored to greatness. Brahms had been emulating Baroque models for six years or more.[5] In particular, between the time he wrote his previous Two Sets of Variations for piano, (No. 1, Eleven Variations on an Original Theme, in D major (1857) and No. 2, Fourteen Variations on a Hungarian Melody, in D major (1854)), Op. 21, and the Handel Variations, Op. 24, Brahms did a careful study of "more rigorous, complex and historical models, among others preludes, fugues, canons and the then obscure dance movements of the Baroque period.[6] Two gigues and two sarabandes that Brahms wrote to develop his technique are extant today.[7] The results of these historical studies are seen in his choice of Handel for the theme, as well as his use of Baroque forms, including the Siciliana dance form (Var. 19) from the French school of Couperin and, in general, the frequent use of contrapuntal techniques in many variations. One aspect of his approach to variation writing is made explicit in a number of letters. "In a theme for a [set of] variations, it is almost only the bass that has any meaning for me. But this is sacred to me, it is the firm foundation on which I then build my stories. What I do with a melody is only playing around ... If I vary only the melody, then I cannot easily be more than clever or graceful, or, indeed, [if] full of feeling, deepen a pretty thought. On the given bass, I invent something actually new, I discover new melodies in it, I create." The role of the bass is critical.

Brahms also took into careful account the character of the theme, and its historical context. Unlike the great model of Beethoven's Diabelli Variations, where the variations departed widely from the character of the theme, Brahms's variations expressed and developed the character of the theme. Because the theme for the Handel variations originated in the Baroque era, Brahms included forms such as a siciliana, a musette, a canon and a fugue.[9] Still not fully established in his career in 1861, Brahms had to struggle to get the work published. He wrote to Breitkopf & Härtel, "I am unwilling, at the first hurdle, to give up my desire to see this, my favourite work, published by you. If therefore, it is primarily the high fee that stops you taking it, I will be happy to let you have it for 12 Friedrichsdors or, if this still seems too high, 10 Friedrichsdors. I very much hope you will not think I plucked the initial fee arbitrarily out of the air. I consider this work to be much better than my earlier ones; I think it is also much better adapted to the demands of performance and will therefore be easier to market ..."[10] The theme of the Handel Variations is taken from an aria in the third movement of Handel's Harpsichord Suite No. 1 in B♭ Major, HWV 434 (Suites de pièces pour le clavecin, published by J. Walsh, London 1733 with five variations). Brahms himself owned a copy of the 1733 First Edition.[11] The appeal of the aria for Brahms might have been its simplicity: its range is restricted to one octave; the harmony is plain, with every note taken from the B-flat major scale; it "made an admirably neutral starting-place".[12] While Handel had written only five variations on his theme, Brahms, with the piano as his instrument rather than the more limited harpsichord, enlarged the scope of his opus to 25 variations ending with an extended fugue. Brahms's use of Handel exemplifies his love of the music of the past and his tendency to incorporate it and transform it in his own compositions. Of the overall concept of the work, Malcolm MacDonald writes "Some of Brahms's models in this monumental work are easy enough to identify. In the scale and ambition of his conception both Bach's 'Goldberg' and Beethoven's 'Diabelli Variations' must have exercised a powerful if generalized influence; in specific features of form Beethoven's 'Eroica' Variations is a closer parallel. But the overall structure is original to Brahms." And MacDonald suggests what might have been a more contemporary source of inspiration, the Variations on a Theme of Handel, Op. 26, by Robert Volkmann. "Brahms might well have known that large and often admirable work, published as recently as 1856, which Volkmann based on the so-called 'Harmonious Blacksmith' theme from the Air with Variations in Handel's E major Harpsichord Suite."[13] StructureIn Music, Imagination, and Culture Nicholas Cook gives the following concise description:

There are various opinions about the organization of the Handel Variations. Hans Meyer, for example, sees the divisions as nos. 1–8 ('strict'), 9–12 ('free'), 13 ('synthesis'), 14–17 ('strict') and 18–25 ('free'), culminating in the fugue.[15] William Horne emphasizes paired variations: nos. 3 and 4, 5 and 6, 7 and 8, 11 and 12, 13 and 14, 23 and 24. This helps him to group the set as 1–8, 9–18, 19–25, with each group ending with a fermata and preceded by one or more variation pairs.[16] John Rink, focusing on Brahms's dynamic markings, writes,

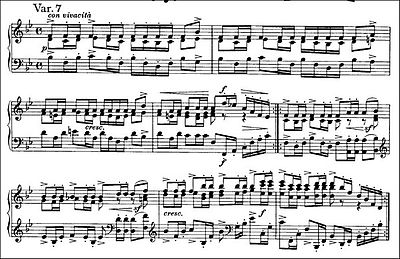

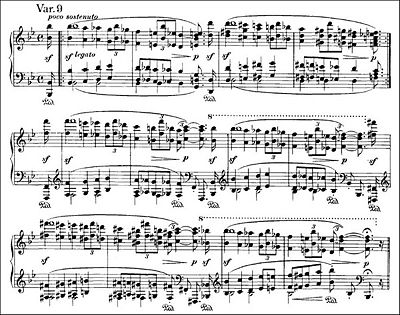

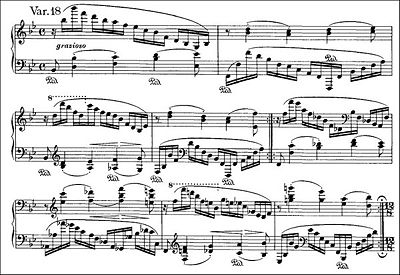

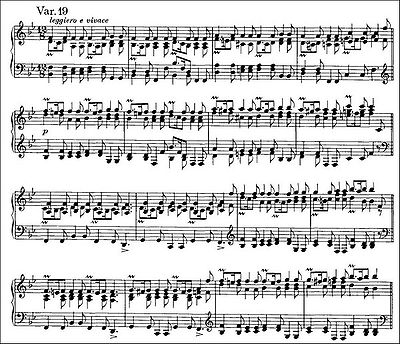

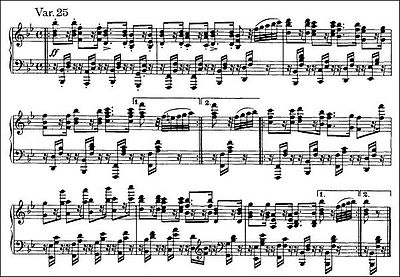

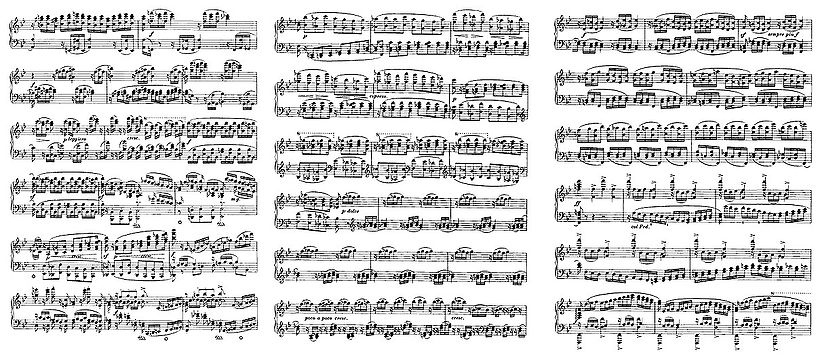

Unity is maintained, at least in part, by using Handel's key signature of B♭ major throughout most of the set, varied by only a few exceptions in the tonic minor, and by repeating Handel's four-bar/two-part structure, including the repeats, in most of the work. The variationsThe performer of the audio files in this section is Martha Goldstein.  Theme. AriaHandel's theme is divided into two parts, each four bars in length and each repeated. The elegant aria moves in stately quarter notes in 4  Variation 1Brahms's first variation stays close to the melody and harmonies of Handel's theme while changing its character completely. It uses staccato throughout and its syncopated accents are distinctly non-Baroque. The dynamic marking poco f (a bit louder), too, clearly separates it from Handel's elegant aria. In tempo the variation seems much more hurried, crisp, even dance-like; each time the right hand "pauses" on an eighth note, the left hand fills in with sixteenth notes. At the end of the two sections, Brahms replaces Handel's decorations with brilliant up- and down-scale runs.  Variation 2Minor-key inflections in Variations 2 to 4 increase the distance from Handel and lay the groundwork for Variations 5 and 6, in the tonic minor. Variation 2 is a subtle piece with a flowing, lilting rhythm. Complexity is added as Brahms uses a favourite technique, found throughout his works, with triple time in one voice—in this case, triplets in the right hand—against duple time in the other. While explicitly recalling the melody of Handel's theme, the chromaticism of this variation adds to the sense of a world beyond the Baroque. In the first half the pattern is of phrases rising on the scale with a crescendo, then falling away in a shorter decrescendo. The second half climbs both in pitch and dynamics to a high climax, again falling away quickly. There is a smooth transition to the next variation.  Variation 3The elegant third variation, marked dolce, moves at a more leisurely pace, providing a sense of calm after two rather busy variations. It also provides a much-needed contrast with the following thunderous variation. Right and left hands alternate and overlap, the left imitating the right in a pattern of three eighth notes. The first note of each group is played staccato, adding to the sense of lightness. The occasional rolled chord adds interest.  Variation 4The fourth variation, marked risoluto, is a showpiece, with sixteenth notes played in octaves in both hands, strong accents (the sforzandos are frequently emphasized by six-note chords) and climaxes that rise a full octave higher than Handel's theme. The charging, syncopated rhythm places the stress on the last sixteenth note of almost every beat. Although no tempo indications are given, this variation is often performed at great speed.  Variation 5After the mighty sounds of the previous variation, the lyrical fifth variation begins quietly. The change of mood is emphasized by a shift to the tonic minor (B♭ minor). This is the first variation in a key different from Handel's. Numerous small crescendos and decrescendos underscore the espressivo marking. The melody moves upward at a measured pace in eighth notes while the left hand accompanies with broken chords in sixteenth notes in contrary motion. The mood is peaceful and tranquil. A pairing between this variation and the following one is created by the use of the tonic minor key signature and contrary motion.  Variation 6Like the preceding variation, this piece is in the tonic minor and features contrary motion, and the motives of the two variations are similar. Marked p sempre with legato phrasing, Variation 6 has a hushed, mysterious tone. The pace is measured, as both hands are written mainly in eighth notes with short sequences of sixteenth notes providing variety. Here Brahms uses counterpoint in the form of a two-part canon in octaves, including inverted canon for several measures in the second half.  Variation 7Echoing the pairing of Variations 5 and 6, the seventh variation is paired with the eighth. Returning to Handel's original B♭ major, Variation 7 is fast, exciting, high-spirited, and fundamentally rhythmic in nature. A sustained drumbeat effect is created by the emphatic repetition of its upper notes and a staccato rhythm throughout all three voices. Because of the repeated upper notes, the focus moves to the inner voices. Numerous accents add further emphasis to the highly rhythmic character of this variation: in some bars in the first half, accents are placed on the last beat of the bar, while in the second half, the accents are yet more numerous, assigned to every beat except the last of each bar. Each half ends in a peak of excitement, marked forte with arpeggios in contrary motion. It leads seamlessly into 8.  Variation 8Variation 8 continues the rhythmic excitement of Variation 7, the left hand beating out, on the same note over and over, the same anapestic rhythm as the preceding variation. After a few bars, the two voices of the right hand are flipped. A fermata at the close provides a moment of silence before 9 begins and signals the end of the first section.  Variation 9Variation 9 slows the pace of the series, with a sense of grandeur as both treble and bass move in stately, ominous octaves. The piece is highly chromatic, and, like several earlier variations, treble and bass are in contrary motion throughout. Each two-bar phrase begins with two exclamatory sf chords, as if sounding an alarm. The variation starts an octave higher than Handel's theme, and its repeated two-bar pattern continually ascends, increasing in tension, until the climax, when it reaches a full two octaves higher than Handel.  Variation 10In contrast to the preceding number, Variation 10 is Allegro energico, fast and exhilarating. Its rather odd effect sounds almost devoid of melody, as the main notes of the theme are scattered among various registers. The first half consists of a series of startling gestures that begin with large, loud chords (f energetico) in the higher registers followed by echoes progressively lower, ending deep in the bass in a series of single notes played pp. The second half rushes to a great climax.  Variation 11After the tension of Variations 7–10, the next two variations are sweet and melodic. Variation 11 uses counterpoint and has a simple, pleasant air with its rock-steady rhythm in the right hand while the left hand simply plays two notes to one. Variations 11 and 12 are another example of the pairing of variations which is so characteristic of the work.  Variation 12The quietness and delicacy of Variation 12 prepares for the return of the dark tonic minor in Variation 13. The left hand is similar to Variation 17, in the same rhythm as the left hand of Handel's theme.  Variation 13Variation 13 returns to the tonic minor in a funereal mood. It is the middle variation of the set and, in the view of Denis Matthews, the emotional centre. Right-hand sixths play against rolled chords in the left, perhaps suggesting muffled drums.[18] For Tovey the lugubrious tone suggests a "kind of Hungarian funeral march", while Malcolm MacDonald sees it as "florid" and "a Hungarian fantasia".[13] Here Brahms abandons the usual repeat signs because each passage that would have been repeated is instead written an octave higher. Variations 13 and 14, while very different in character, are paired in being fast and exciting and in their use of parallel sixths in the right hand.  Variation 14Variation 14, marked sciolto ("loose") breaks the dark mood of Variation 13 and returns to the original key. With its extended trills and scalar runs in sixths in the right hand against broken octaves in the left hand, it is a virtuoso showpiece. The mood is of great energy, excitement, and high spirits. It leads without a break into the following variation. Donald Francis Tovey sees a grouping in Variations 14–18, which he describes as "aris[ing] one out of the other in a wonderful decrescendo of tone and crescendo of Romantic beauty".[19]  Variation 15Following without a pause from the previous number, Variation 15, marked forte, is a bravura variation building relentlessly toward an exciting climax. It consists of a one-bar pattern, varied only slightly, of two declamatory chords in eighth notes in the higher registers, followed by lower sixteenth notes that echo Handel's original turns. A prominent upbeat creates syncopated energy. It has been called an étude for Brahms's Piano Concerto No. 2.[11] It breaks the structural mould of Handel's theme by adding one "extra" bar. In Brahms's first autograph, Variations 15 and 16 were positioned in the reverse order.[20]  Variation 16Variation 16 continues from Variation 15 as a "variation of variation",[21] repeating the pattern of two high eighth notes followed by a run of lower sixteenth notes. It also forms another pairing with Variation 17. Baroque contrapuntal techniques appear again in this canon, described by Malcolm MacDonald as "wittier" than the canon of Variation 6.[13] The left hand begins with two descending staccato eighth notes, immediately followed in the opposite hand by the two eighth notes inverted, a full four octaves higher. In each case, a figure in sixteenth notes follows in canonic imitation. The effect is light and exhilarating.  Variation 17In Variation 17, the absence of the sixteenth notes that were so prominent in the preceding two variations gives the impression of a slowing, despite the marking of più mosso. The effect is of gently falling raindrops, with gracefully descending broken chords in the right hand, piano and staccato, repeated throughout the work at various pitches. Each note is played twice, adding to the suggestion of a leisurely pace.  Variation 18Another "variation of a variation", paired with the preceding Variation 17.[21] The accompaniment from the previous variation, which now echoes the melody of the aria, is now syncopated and alternating between the hands, while the "raindrops" are replaced by sweeping arpeggios.  Variation 19This slow, relaxing variation, with its lilting rhythm and 12 Variation 20 From the outset, Variation 20 builds toward its climax. In contrast to the preceding variation, there is little of the Baroque in it with its chromaticism in both treble and bass and its thick textures (triads in the right hand against octaves in the left hand). Malcolm MacDonald refers to its "organ-loft progressions".[13]  Variation 21Variation 21 moves to the relative minor (G minor). Like Variation 19, the theme is hidden, in this case by merely gracing the main notes of the theme in passing, thereby achieving a sense of lightness. It is another example of Brahms' use of polyrhythms, this time pairing three notes against four.  Variation 22The light mood of the preceding variation continues in Variation 22. Often referred to as the "musical-box" variation because of the regularity of its rhythm, underlined particularly by a drone bass,[13] Variation 22 alludes to the Baroque musette, a soft pastoral air imitating the sound music of a bagpipe, or musette. It remains in the high registers, consistently above Handel's theme, the lowest note being the repeated B♭ of the drone. The light mood prepares the way for the climactic, concluding section which, in Tovey's words, comes "swarming up energetically out of darkness".[23]  Variation 23At Variation 23 the rise toward a final climax begins. It is clearly paired with the following Variation 24, which continues its pattern but in a more hurried, more urgent manner.  Variation 24In preparation for the climactic final variation, Variation 24 intensifies the excitement, replacing the triplets of Variation 23 with masses of sixteenth notes. Clearly modeled on the preceding, it is another example of Brahms's use of "variation of variation".[21]  Variation 25An exultant showpiece, Variation 25 ends the variations and leads into the concluding fugue. Its strong resemblance to Variation 1 ties the set together, as they both feature a left hand which fills the pauses in the right. FugueThe powerful concluding fugue brings the variation set to a climactic close. Its subject, repeated many times from beginning to end, derives from the opening of Handel's theme. At its most microscopic level, the subject comes solely from the ascending major second from the first two beats in the top voice of Handel's theme. The ascending second is stated twice in sixteenth notes and repeated again a major third higher. This parallels the first measure of Handel's theme, which ascends from B♭ to C to D to E♭. The following melodic line of the second measure resembles the second measure of Handel's theme in general trajectory (Brahms's theme is also strikingly similar to the subject of Fugue VI from Felix Mendelssohn's Six Preludes and Fugues, Op. 35, also in B♭ major). Julian Littlewood observes that the fugue has "a dense contrapuntal argument which recalls Bach more than Handel".[11] Denis Matthews adds that it is "more redolent of one of Bach's great organ fugues than any in The Well-Tempered Clavier, with inversions, augmentation and double counterpoint to match, and a great peroration over a swinging dominant pedal-point".[24] Despite its magnitude, Littlewood suggests, the fugue avoids separation from the rest of the set by its comparable texture. "In this way it systematically creates a web of links between past and present, achieving synthesis rather than quotation or parody." Michael Musgrave in The Music of Brahms writes,

Reception and aftermathAn entry in Clara Schumann's diary about the Handel Variations gives an idea of how close the relationship between her and Brahms was, as well as Brahms's sometimes extraordinary insensitivity: "On Dec 7th I gave another soirée, at which I played Johannes' Handel Variations. I was in agonies of nervousness, but I played them well all the same, and they were much applauded. Johannes, however, hurt me very much by his indifference. He declared that he could no longer bear to hear the variations, it was altogether too dreadful for him to listen to anything of his own and to have to sit by and do nothing. Although I can well understand this feeling, I cannot help finding it hard when one has devoted all one's powers to a work, and the composer himself has not a kind word for it."[26] Yet in the following spring (April 1862) Brahms wrote, in a note to a critic to whom he was sending a copy of the work, "I am fond of it and value it particularly in relation to my other works".[27] Clara Schumann premiered the work in Hamburg on December 7, when she visited Brahms's home town to give a series of performances, which also included the Piano Concerto No. 1 in D minor—which had not been well received when Brahms introduced it to Leipzig in the Gewandhaus in January 1858—and the premiere of the Piano Quartet No. 1 in G minor. Clara's performance of the Handel Variations in Hamburg was a triumph, which she repeated soon afterward in Leipzig. During that winter, Brahms also gave performances of the Handel Variations, as a result of which he made minor alterations to the score.[20] Publication came in July 1862 by Breitkopf & Härtel. With the "complete failure,[28]" as he described it to Clara, of his first large-scale orchestral work, the First Piano Concerto, the Handel Variations became an important landmark in the developing career of Brahms. Another seven years passed before his reputation was firmly established by A German Requiem in Bremen in 1868, and it took a full fifteen years before he made his mark as a symphonist with his first symphony (1876). During what was probably the first meeting of Brahms and Richard Wagner in January 1863, Brahms performed his Handel Variations. Despite the great differences between the two men in musical style and an underlying tension based on musical politics—Brahms championing a more conservative approach to music while Wagner, along with Franz Liszt, called for "the music of the future" with new forms and new tonalities—Wagner complimented the work graciously, if not wholeheartedly, saying, "One sees what still may be done in the old forms when someone comes along who knows how to use them".[29] ArrangementsThe piece is often heard in a version that was arranged for orchestra by the British composer and Brahms enthusiast Edmund Rubbra in 1938. The orchestration was first performed at a Royal Philharmonic Society concert conducted by Adrian Boult.[30] The ballet Brahms/Handel, made by New York City Ballet balletmaster Jerome Robbins in collaboration with Twyla Tharp, was set to this orchestration.[31] The work has also been transcribed for solo organ by French-Canadian composer Rachel Laurin.[32] RecordingsRecordings of the set on a 19th-century piano include:

Notes

External links

|

||||||||||||||||