|

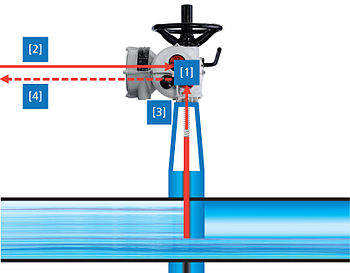

Valve actuator A valve actuator is the mechanism for opening and closing a valve. Manually operated valves require someone in attendance to adjust them using a direct or geared mechanism attached to the valve stem. Power-operated actuators, using gas pressure, hydraulic pressure or electricity, allow a valve to be adjusted remotely, or allow rapid operation of large valves. Power-operated valve actuators may be the final elements of an automatic control loop which automatically regulates some flow, level or other process. Actuators may be only to open and close the valve, or may allow intermediate positioning; some valve actuators include switches or other ways to remotely indicate the position of the valve. Used for the automation of industrial valves, actuators can be found in all kinds of process plants. They are used in waste water treatment plants, power plants, refineries, mining and nuclear processes, food factories, and pipelines. Valve actuators play a major part in automating process control. The valves to be automated vary both in design and dimension. The diameters of the valves range from one-tenth of an inch to several feet. TypesThe common types of actuators are: manual, pneumatic, hydraulic, electric and spring. ManualA manual actuator employs levers, gears, or wheels to move the valve stem with a certain action. Manual actuators are powered by hand. Manual actuators are inexpensive, typically self-contained, and easy to operate by humans. However, some large valves are impossible to operate manually and some valves may be located in remote, toxic, or hostile environments that prevent manual operations in some conditions. As a safety feature, certain types of situations may require quicker operation than manual actuators can provide to close the valve. PneumaticAir (or other gas) pressure is the power source for pneumatic valve actuators.[1] They are used on linear or quarter-turn valves. Air pressure acts on a piston or bellows diaphragm creating linear force on a valve stem. Alternatively, a quarter-turn vane-type actuator produces torque to provide rotary motion to operate a quarter-turn valve. A pneumatic actuator may be arranged to be spring-closed or spring-opened, with air pressure overcoming the spring to provide movement. A "double acting" actuator use air applied to different inlets to move the valve in the opening or closing direction. A central compressed air system can provide the clean, dry, compressed air needed for pneumatic actuators. In some types, for example, regulators for compressed gas, the supply pressure is provided from the process gas stream and waste gas either vented to air or dumped into lower-pressure process piping. HydraulicHydraulic actuators convert fluid pressure into motion. Similar to pneumatic actuators, they are used on linear or quarter-turn valves. Fluid pressure acting on a piston provides linear thrust for gate or globe valves. A quarter-turn actuator produces torque to provide rotary motion to operate a quarter-turn valve. Most types of hydraulic actuators can be supplied with fail-safe features to close or open a valve under emergency circumstances. Hydraulic pressure can be supplied by a self-contained hydraulic pressure pump. In some applications, such as water pumping stations, the process fluid can provide hydraulic pressure, although the actuators must use materials compatible with the fluid.  ElectricThe electric actuator uses an electric motor to provide torque to operate a valve. They are quiet, non-toxic and energy efficient. However, electricity must be available, which is not always the case, they can also operate on batteries. SpringSpring-based actuators hold back a spring. Once any anomaly is detected, or power is lost, the spring is released, operating the valve. They can only operate once, without resetting, and so are used for one-use purposes such as emergencies. They have the advantage that they do not require a powerful electric supply to move the valve, so they can operate from restricted battery power, or automatically when all power has been lost. Actuator movement A linear actuator opens and closes valves that can be operated via linear force, the type sometimes called a "rising stem" valve. These types of valves include globe valves, rising stem ball valves, control valves and gate valves.[2] The two main types of linear actuators are diaphragm and piston. Diaphragm actuators are made out of a round piece of rubber and squeezed around its edges between two side of a cylinder or chamber that allows air pressure to enter either side pushing the piece of rubber one direction or the other. A rod is connected to the center of the diaphragm so that it moves as the pressure is applied. The rod is then connected to a valve stem which allows the valve to experience the linear motion thereby opening or closing. A diaphragm actuator is useful if the supply pressure is moderate and the valve travel and thrust required are low. Piston actuators use a piston which moves along the length of a cylinder. The piston rod conveys the force on the piston to the valve stem. Piston actuators allow higher pressures, longer travel ranges, and higher thrust forces than diaphragm actuators. A spring is used to provide defined behavior in the case of loss of power. This is important in safety related incidents and is sometimes the driving factor in specifications. An example of loss of power is when the air compressor (the main source of compressed air that provides the fluid for the actuator to move) shuts down. If there is a spring inside of the actuator, it will force the valve open or closed and will keep it in that position while power is restored. An actuator may be specified "fail open" or "fail close" to describe its behavior. In the case of an electric actuator, losing power will keep the valve stationary unless there is a backup power supply. A typical representative of the valves to be automated is a plug-type control valve. Just like the plug in the bathtub is pressed into the drain, the plug is pressed into the plug seat by a stroke movement. The pressure of the medium acts upon the plug while the thrust unit has to provide the same amount of thrust to be able to hold and move the plug against this pressure. Features of an electric actuator Motor (1)Robust asynchronous three-phase AC motors are mostly used as the driving force, for some applications also single-phase AC or DC motors are used. These motors are specially adapted for valve automation as they provide higher torques from standstill than comparable conventional motors, a necessary requirement to unseat sticky valves. The actuators are expected to operate under extreme ambient conditions, however they are generally not used for continuous operation since the motor heat buildup can be excessive. Limit and torque sensors (2)The limit switches signal when an end position has been reached. The torque switching measures the torque present in the valve. When exceeding a set limit, this is signaled in the same way. Actuators are often equipped with a remote position transmitter which indicates the valve position as continuous 4-20mA current or voltage signal. Gearing (3)Often a worm gearing is used to reduce the high output speed of the electric motor. This enables a high reduction ratio within the gear stage, leading to a low efficiency which is desired for the actuators. The gearing is therefore self-locking i.e. it prevents accidental and undesired changes of the valve position by acting upon the valve’s closing element. Valve attachment (4)The valve attachment consists of two elements. First: The flange used to firmly connect the actuator to the counterpart on the valve side. The higher the torque to be transmitted, the larger the flange required. Second: The output drive type used to transmit the torque or the thrust from the actuator to the valve shaft. Just like there is a multitude of valves there is also a multitude of valve attachments. Dimensions and design of valve mounting flange and valve attachments are stipulated in the standards EN ISO 5210 for multi-turn actuators or EN ISO 5211 for part-turn actuators. The design of valve attachments for linear actuators is generally based on DIN 3358. Manual operation (5)In their basic version most electric actuators are equipped with a handwheel for operating the actuators during commissioning or power failure. The handwheel does not move during motor operation. The electronic torque limiting switches are not functional during manual operation. Mechanical torque-limiting devices are commonly used to prevent torque overload during manual operation. Actuator controls (6)Both actuator signals and operation commands of the DCS are processed within the actuator controls. This task can in principle be assumed by external controls, e.g. a PLC. Modern actuators include integral controls which process signals locally without any delay. The controls also include the switchgear required to control the electric motor. This can either be reversing contactors or thyristors which, being an electric component, are not subject to mechanic wear. Controls use the switchgear to switch the electric motor on or off depending on the signals or commands present. Another task of the actuator controls is to provide the DCS with feedback signals, e.g. when reaching a valve end position. Electrical connection (7)The supply cables of the motor and the signal cables for transmitting the commands to the actuator and sending feedback signals on the actuator status are connected to the electrical connection. The electrical connection can be designed as a separately sealed terminal bung or plug/socket connector. For maintenance purposes, the wiring should be easily disconnected and reconnected. Fieldbus connection (8)Fieldbus technology is increasingly used for data transmission in process automation applications. Electric actuators can therefore be equipped with all common fieldbus interfaces used in process automation. Special connections are required for the connection of fieldbus data cables. FunctionsAutomatic switching off in the end positionsAfter receiving an operation command, the actuator moves the valve in direction OPEN or CLOSE. When reaching the end position, an automatic switch-off procedure is started. Two fundamentally different switch-off mechanisms can be used. The controls switch off the actuator as soon as the set tripping point has been reached. This is called limit seating. However, there are valve types for which the closing element has to be moved in the end position at a defined force or a defined torque to ensure that the valve seals tightly. This is called torque seating. The controls are programmed as to ensure that the actuator is switched off when exceeding the set torque limit. The end position is signalled by a limit switch. Safety functionsThe torque switching is not only used for torque seating in the end position, but it also serves as overload protection over the whole travel and protects the valve against excessive torque. If excessive torque acts upon the closing element in an intermediate position, e.g. due to a trapped object, the torque switching will trip when reaching the set tripping torque. In this situation the end position is not signalled by the limit switch. The controls can therefore distinguish between normal operation torque switch tripping in one of the end positions and switching off in an intermediate position due to excessive torque. Temperature sensors are required to protect the motor against overheating. For some applications by other manufacturers, the increase of the motor current is also monitored. Thermoswitches or PTC thermistors which are embedded in the motor windings mostly reliably fulfil this task. They trip when the temperature limit has been exceeded and the controls switch off the motor.  Process control functionsDue to increasing decentralisation in automation technology and the introduction of micro processors, more and more functions have been transferred from the DCS to the field devices. The data volume to be transmitted was reduced accordingly, in particular by the introduction of fieldbus technology. Electric actuators whose functions have been considerably expanded are also affected by this development. The simplest example is the position control. Modern positioners are equipped with self-adaptation i.e. the positioning behaviour is monitored and continuously optimised via controller parameters. Meanwhile, electric actuators are equipped with fully-fledged process controllers (PID controllers). Especially for remote installations, e.g. the flow control to an elevated tank, the actuator can assume the tasks of a PLC which otherwise would have to be additionally installed. DiagnosisModern actuators have extensive diagnostic functions which can help identify the cause of a failure. They also log the operating data. Study of the logged data allows the operation to be optimised by changing the parameters and the wear of both actuator and valve to be reduced. Duty types  Open-close dutyIf a valve is used as a shut-off valve, then it will be either open or closed and intermediate positions are not held... Positioning dutyDefined intermediate positions are approached for setting a static flow through a pipeline. The same running time limits as in open-close duty apply. Modulating dutyThe most distinctive feature of a closed-loop application is that changing conditions require frequent adjustment of the actuator, for example, to set a certain flow rate. Sensitive closed-loop applications require adjustments within intervals of a few seconds. The demands on the actuator are higher than in open-close or positioning duty. Actuator design must be able to withstand the high number of starts without any deterioration in control accuracy. Service conditions  Actuators are specified for the desired life and reliability for a given set of application service conditions. In addition to the static and dynamic load and response time required for the valve, the actuator must withstand the temperature range, corrosion environment and other conditions of a specific application. Valve actuator applications are often safety related, therefore the plant operators put high demands on the reliability of the devices. Failure of an actuator may cause accidents in process-controlled plants and toxic substances may leak into the environment. Process-control plants are often operated for several decades which justifies the higher demands put on the lifetime of the devices. For this reason, actuators are always designed in high enclosure protection. The manufacturers put a lot of work and knowledge into corrosion protection. Enclosure protectionThe enclosure protection types are defined according to the IP codes of EN 60529. The basic versions of most electric actuators are designed to the second highest enclosure protection IP 67. This means they are protected against the ingress of dust and water during immersion (30 min at a max. head of water of 1 m). Most actuator manufacturers also supply devices to enclosure protection IP 68 which provides protection against submersion up to a max. head of water of 6 m. Ambient temperaturesIn Siberia, temperatures down to – 60 °C may occur, and in technical process plants + 100 °C may be exceeded. Using the proper lubricant is crucial for full operation under these conditions. Greases which may be used at room temperature can become too solid at low temperatures for the actuator to overcome the resistance within the device. At high temperatures, these greases can liquify and lose their lubricating power. When sizing the actuator, the ambient temperature and the selection of the correct lubricant are of major importance. Explosion protectionActuators are used in applications where potentially explosive atmospheres may occur. This includes among others refineries, pipelines, oil and gas exploration or even mining. When a potentially explosive gas-air-mixture or gas-dust-mixture occurs, the actuator must not act as ignition source. Hot surfaces on the actuator as well as ignition sparks created by the actuator have to be avoided. This can be achieved by a flameproof enclosure, where the housing is designed to prevent ignition sparks from leaving the housing even if there is an explosion inside. Actuators designed for these applications, being explosion-proof devices, have to be qualified by a test authority (notified body). Explosion protection is not standardized worldwide. Within the European Union, ATEX 94/9/EC applies, in US, the NEC (approval by FM) or the CEC in Canada (approval by the CSA). Explosion-proof actuators have to meet the design requirements of these directives and regulations. Additional usesSmall electric actuators can be used in a wide variety of assembly, packaging and testing applications. Such actuators can be linear, rotary, or a combination of the two, and can be combined to perform work in three dimensions. Such actuators are often used to replace pneumatic cylinders.[4] ReferencesWikimedia Commons has media related to Valve actuators.

|