|

United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Western Asia

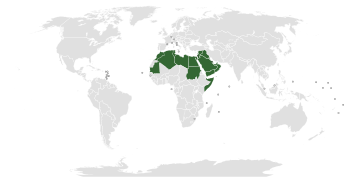

The United Nations Economic and Social Commission for West Asia (ESCWA; Arabic: الإسكوا) is one of five regional commissions under the jurisdiction of the United Nations Economic and Social Council. The role of the Commission is to promote economic and social development of Western Asia through regional and subregional cooperation and integration. The Commission is composed of 21 member states, all from the regions of North Africa and the Middle East.[1] The Commission works closely with the divisions of the Headquarters in New York and United Nations specialized agencies, as well as with international and regional organizations. The League of Arab States, the Gulf Cooperation Council and the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation are among its regional partners.[2] HistoryThe Commission was first established by the Economic and Social Council on 9 August 1973 as the United Nations Economic Commission for Western Asia (ECWA). The Commission was the successor to the United Nations Economic and Social Office in Beirut (UNESOB), which was absorbed into the framework of ECWA.[3] Its main mandate was to "initiate and participate in measures for facilitating concerted action for the economic reconstruction and development of Western Asia."[4] On 26 July 1985, in recognition of the social component of its work, the Commission was renamed to the United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Western Asia (ESCWA) by the Economic and Social Council.[5][2] Member States The following are all member States of the Commission:[6] Locations The Commission's headquarters have been located in the Central District of Beirut, Lebanon, since 1997. Prior to this, the headquarters moved between multiple cites. The first headquarters of the Commission were located in Beirut from 1974 to 1982. They then moved to Baghdad, Iraq, from 1982 to 1991. Finally, they were located in Amman, Jordan, from 1991 to 1997 before moving back to Beirut.[2] Executive SecretariesThe following is a list of the Executive Secretaries of the Commission since its foundation:[7]

FundingThe budget of Commission comes mainly from contributions from the United Nations, but also from donations from governments, regional funds, private foundations and international development agencies. In 2017, the total budget of the Commission was US$27.4 million.[8] Additionally, since 2014, the Commission has received $7.1 million in voluntary contributions to help implement national and regional activities.[9] The Commission has four main budgets: the regular budget, the regular programme of technical cooperation (RPTC), the development account and the extrabudgetary projects account. Regular budgetThe regular budget line item is voted on by the United Nations General Assembly on a biennial basis and provides the Commission with resources fulfil its mandate as laid out in the Strategic Framework. In 2017, the regular budget was $19.9 million.[8] Regular programme of technical cooperation (RPTC)The regular programme of technical cooperation line item works to support member states in formulating sustainable socioeconomic development policies. In 2017, the regular programme of technical cooperation budget was $2.3 million.[8] Development accountThe development account line item helps fund capacity building projects at national, subregional, regional and interregional levels. In 2017, the development account budget was $1.9 million.[8] Extrabudgetary projectsThe extra budgetary projects line item supports economic and social development under the seven subprograms of the Commission: Economic Development and Integration, Gender and Women Issues, Governance and Conflict Issues, Natural Resources, Social Development, Statistics and Technology for Development. In 2017, extra budgetary projects budget was $3.2 million.[8] Israel-Palestine report controversyOn 15 March 2017, UNESCWA released a report accusing Israel (not a UNESCWA member state) of being an "apartheid regime" due to Israel's relations with Palestinians both inside and outside Israel.[10][11] The report was officially withdrawn and removed from UN websites after criticism from the Secretary-General who said it had been issued by ESCWA without approval.[12] The document was co-authored by Richard Falk, professor of International Law and Practice Emeritus at Princeton University and a former UN human rights investigator for the Palestinian territories, and Virginia Tilley, professor of Political Science at Southern Illinois University.[13] It criticised Israel's law of return for Jews.[12] Falk and Tilley wrote: "Israel defends its rejection of the Palestinians' return in frankly racist language: alleging that Palestinians constitute a 'demographic threat' and that their return would alter the demographic character of Israel to the point of eliminating it as a Jewish state".[14] Rima Khalaf, United Nations Under-Secretary-General and Executive Secretary of ESCWA, had said it was the first to accuse Israel of being a racist state which had established an apartheid system.[10][15] The report itself said it had established on the "basis of scholarly inquiry and overwhelming evidence, that Israel is guilty of the crime of apartheid". Israel has condemned the report. "We expected of course that Israel and its allies would put huge pressure on the Secretary-General of the United Nations so that he would disavow the report, and that they would ask him to withdraw it," Khalaf said to AFP.[15] UN Secretary-General António Guterres distanced himself from the report[12] and the document was removed from UN website on Friday, 17 March 2017.[16] The report's Executive Summary was also deleted from the United Nations Information System on the Question of Palestine (UNISPAL).[17] On 17 March, Khalaf submitted her letter of resignation to Guterres. Following the strong response from Israel, she wrote: "It is only normal for criminals to pressure and attack those who advocate the cause of their victims." She continued to stand by the report.[18] Women in the JudiciaryIn 2019, ESCWA reported regarding the situation of women in the judiciary system, in which only three countries had not appointed female judges yet, including Oman, Saudi Arabia and Somalia. Other countries which already had female judges were: Iraq (1959), Morocco (1961), Algeria (1962),[19] Sudan (1965[20] or 1976), Lebanon and Tunisia (1966), Yemen (1971), Syria (1975), Palestine (1982), Libya (1991), Jordan (1996), Egypt (2003), Bahrain (2006), the United Arab Emirates (2008), Qatar (2010), Mauritania (2013),[21] and Kuwait (2020).[22] In June 2021, Egypt announced that female judges would take seats in Public Prosecution and State Council in October that year.[23] See also

References

Bibliography

External links |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||