|

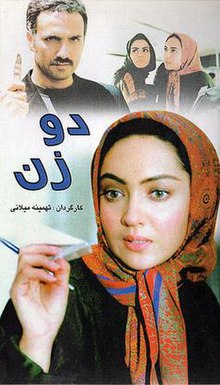

Two Women (1999 film)

Two Women (Do zan) is a 1999 Iranian drama film written and directed by Tahmineh Milani. Two Women charts the lives of two promising architecture students over the course of the first turbulent years of the Islamic Republic, creating a portrait of traditions that conspire to trap women and stop them from realizing their full potential. In an extensive interview, Tahmineh Milani stated that the name Two Women alluded to two different potential life-stories of one woman. The film won the best screenplay award at Iran's Fajr Film Festival in 1999 as well as Best Actress for Niki Karimi's part in the Taormina Film Festival. PlotThe film starts at some fourteen years after Fereshteh (Niki Karimi) and Royā (Merilā Zāre'í) became friends, while studying architecture at a university in Tehran. Fereshteh's husband is in the ICU and she needs Roya's help. The events in the life of Fereshteh over the course of the preceding fourteen years are revealed through a series of flashbacks that represent Feresheh's and Royā's reminiscences. Fereshteh, whose family lives in reduced circumstances in Esfahan, is an excellent student who brims with hopes and expectations for her future and what she would do for her family on graduating. A voracious reader, she seems to know almost everything and is ready to face any difficulty, she has no interest in marrying just yet but instead wants to build a successful career. Fereshteh supports herself financially through giving private tuitions to fellow students. Royā's family, on the other hand, are wealthy. She becomes one of Fereshteh's private pupils and through this a deep friendship develops between the two. Fereshteh is stalked by an obsessive young man, named Hassan (Mohammad-Rezā Foroutan), who stops at nothing for gaining her attention and, as he puts it, marrying her. He stirs up many problems, including inflicting serious bodily harm by throwing acid to Fereshteh's cousin on mistaking him as Fereshteh's boyfriend. This prompts Fereshteh's father (Rezā Khāndān) forcing her to return to their home in Esfahan (although Fereshteh lives independently in a university dormitory, she is formally in the care of her uncle, her father's brother, who lives in Tehran); through some inverted logic, the father believes that the actions of the stalker must have been provoked by some impropriety on the part of his daughter. These events take place at the time when the universities are being closed by the government of Iran (which in reality took place in the second half of 1979) so that Fereshteh does not see her departure from Tehran as life-changing, but as a temporary event with no consequence for her studies and her future plans. The stalker follows Fereshteh to Esfahan and during a motorcycle-car chase causes a fatal accident involving two children playing football on street. This ultimately causes the stalker to be sentenced to 13 years in prison - as he's dragged away to prison he vows to kill Fereshteh when he's released. A man, named Ahmad (Atila Pesiani), who helps Fereshteh and her family with the legal case and fees ensuing this accident, asks Fereshteh's hand and despite Fereshteh's initial fierce opposition to the proposal, by promising to be supportive of Fereshteh's plan to pursue her studies following the opening of universities, succeeds in gaining Fereshteh's consent and the two marry. After the marriage, he proves to be an utterly jealous husband who bars Fereshteh from having any contact with the outside world that he does not approve of, including association with Royā; although he does not know Royā at all, he feels a visceral hatred towards her, believing that she represents the liberal society that he finds so detestable. When Fereshteh applies to court for divorce, the presiding judge dismisses the case outright, stating that none of the actions of her husband, that suffocate her both emotionally and intellectually, were sufficient for the court to grant divorce. The judge's decision is based on Fereshteh answering a series of questions, such as whether her husband was violent, whether he was unfaithful, whether he had a drug addiction, etc., in the negative; in response to Fereshteh's repeated pleas and appeal to her being a human being, the judge retorts not to waste the time of the court. It is remarkable that although one never sees Ahmad beating Fereshteh, in reality he is a violent man, as he constantly verbally abuses Fereshteh and often brandishes a kitchen knife while doing so; this is Milāni's subtle way of showing how domestic violence is often not recognized even by its very victims. Fereshteh and her husband have two sons (both in their teens when Fereshteh and Royā meet after fourteen years) who outwardly love both parents equally, but inwardly stand on the side of their mother, who, amongst others, teaches them to the best of her ability. Fereshteh tries to leave her husband multiple times but events conspire against her and she's unable to do so, until 13 years have passed and the stalker is once again at her doorstep. Finally after yet another fight with her controlling husband (he finds out she's been secretly acquiring and reading books, including those about childcare) she runs out of her home, chased by Ahmad. She's able to temporarily make headway, but runs into her old stalker instead. Giving up, she tells the stalker to kill her like he wants to, but Ahmad intervenes and is stabbed instead. This is the incident that has landed him in the ICU at the beginning of the movie. As Fereshtah finishes telling her story to Roya, the phone rings and they are informed of Ahmad's death. Fereshteh is upset yet for the first time in years she sees a hopeful light ahead. She says she didn't want Ahmad to die despite all he did, but now that he is dead she has so much to do - go back to university, earn an income and be both parents to her sons. With increasing excitement she talks about reading books, learning to drive, learning computers. Finally she asks Roya to help her find books about single mothers raising their children alone. Cast

Part of film-scriptFereshteh: My family does not like a girl to enter the police station. No, it is not fair. We need to make our own group. Roya: What group? Fereshteh: A group which belongs to us. Apachi Girls! What do you think? Roya: You're crazy. Fereshteh: World does not work like that! We should not stand seeing a stubborn boy bothering and insulting us in the street and saying nothing. We need to make ourselves powerful. We need to learn karate. We need to work out and do body building. Significance of the above dialogueThe above dialogue is of the scenes of the movie Two Women in which two friends are talking about creating a group in order to gain power to protect themselves as the weaker gender. Made in 1999, the film reflects the patriarchal society of Iran after the Islamic Republic when men would shape and limit all aspects of a woman’s life such as her education, career, lifestyle, goals, and marriage. Unlike previous films in the cinema of Iran, the leading character of Two Women (Do Zan) is a lady naming Fereshteh which means angel. Instead of showing her as a typical housewife whose only purpose is to fulfill the expectations of a father and husband, the film focuses on the subjectivity of Fereshteh as a rebellion, too, far from the meaning of angel and an ideal Persian woman, who is adventurous, literate, decisive, and purposeful. She thinks independently and works as a teacher not only to use her knowledge but also to help her family financially which is so uncommon of a woman at her time. For the very first time, Milani directs a film based on the total presence of a woman, her feelings and thoughts, and shows the world how a woman's life is objectified in a patriarchal society and how the men can turn a strong, independent woman to a helpless, broken one. About the filmmakerTahmineh Milani was born in 1960. She is a professional film director, screenwriter, and producer who came to the limelight by challenging traditional and conventional norms about women and their presence in Iran's society. Being sentenced to prison has not stopped her from expressing her feminist ideas freely and her style has become a canon against which other feminist works are evaluated. See alsoReferences

External links

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||