|

Trochosaurus

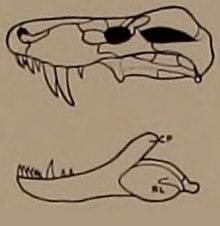

Trochosaurus (from Greek: τρόχoς trókhos, 'badger' and Greek: σαῦρος saûros, 'lizard') is a dubious genus of therocephalian therapsid from South Africa, to which various species were once assigned. The genus was based upon multiple weathered and distorted fossils of therocephalians of the family Lycosuchidae. Like other lycosuchids, specimens placed in Trochosaurus have only five large incisors in each premaxilla, seemingly two functional "double canines" in each maxilla (of which the second was supposedly slightly larger in Trochosaurus), and few postcanines. However, the fossils lack any further diagnostic traits to justify referring them to their own genus, or to any species therein. Hence, Trochosaurus is now considered to be a nomen dubium (dubious name) and is disused, as are all its assigned species.[1][2] Trochosaurus was originally distinguished from other "double canined" therocephalians known at the time (Lycosuchus and Trochosuchus) only by the combination of Trochosuchus-like jaw proportions (shallower upper jaws and deeper lower jaws) with roughly equal-sized "double canines" as seen in Lycosuchus (unlike the smaller first canine described for Trochosuchus).[3] However, such proportional differences are subject to distortion, and the variable size of lycosuchid canines is now recognised to only represent different stages of tooth growth and replacement.[a] Furthermore, the poor condition of the fossils obscures any potentially useful diagnostic features, and so the specimens themselves can only be assigned to Lycosuchidae incertae sedis.[1][2] All specimens referred to Trochosaurus—including the three holotypes—are poorly preserved and badly worn, and mostly consist only of partial skulls representing the snout and jaws up to around the orbits. Specimens for which the locality data is known were collected from the Prince Albert district and come from the Abrahamskraal Formation within the Capitanian-aged Tapinocephalus Assemblage Zone of the Middle Permian. Notably, one specimen (SAM-PK-2756) is among the stratigraphically lowest (and so oldest) lycosuchid fossils known, lower than the oldest recognised records of the valid lycosuchids Lycosuchus and Simorhinella.[1][2] Taxonomy Trochosaurus was named in 1915 by Sidney H. Haughton for the type species T. intermedius (referring to its seemingly intermediate condition between Lycosuchus and Trochosuchus) based on a single specimen, the holotype SAM-PK-2756. This specimen is an extremely weathered partial skull, preserving roughly the first two thirds of the skull and jaws with an estimated total length of ~237 millimetres (9.3 in).[1][3] The species assigned to Trochosaurus have a somewhat confused taxonomic history, as the type species T. intermedius was later synonymised by Robert Broom with another large early therocephalian in 1932, Trochosuchus major.[5] Broom also named Trochosuchus major in 1915 from the holotype AMNH 5543 (a similar weathered partial skull to SAM-PK-2756 about 219 millimetres (8.6 in) long),[1] but did so slightly earlier than Haughton named T. intermedius.[6] Thus, when Broom moved T. major into Trochosaurus and synonymised the two species, the type species T. intermedius became its junior synonym and so formed the new combination of Trochosaurus major. Broom, however, described separating the two genera as provisional, admitting he was uncertain whether Trochosaurus and Trochosuchus could be truly distinguished. Indeed, Romer (1956) and Romer & Watson (1956) later synonymised the two with Trochosuchus as the senior synonym.[2][5][7] At the same time as his synonymisation, Broom referred a third specimen (NHMUK R5747) to T. major. Although also poorly preserved, this specimen is relatively more complete than the two holotypes and both Broom (1932) and Boonstra (1934) used this specimen as the primary basis for illustrating complete skull reconstructions of Trochosaurus. Broom would also name a second species of Trochosaurus, T. dirus, in 1936 from a large partial snout he had cut into multiple sections. Broom justified erecting the new species only on the basis of its larger size and seemingly lower number of postcanine teeth than T. major.[8] However, no specimen number was given and by 1987 the holotype had been lost.[2]  Trochosaurus and its species would remain in use in therocephalian systematics up until 1987, when Juri van den Heever revised early therocephalian taxonomy in his PhD thesis. Van den Heever determined all the specimens referred to Trochosaurus lack any discernible diagnostic features beyond those now recognised for Lycosuchidae. As such, the genus Trochosaurus and its various species are all regarded as nomen dubia by modern researchers and the specimens themselves only represent Lycosuchidae incertae sedis.[1][2][9] Notes

References

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||