|

Triumphs

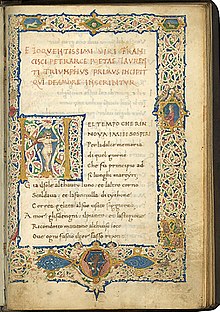

Triumphs (Italian: I Trionfi) is a 14th-century Italian series of poems, written by Petrarch in the Tuscan language. The poem evokes the Roman ceremony of triumph, where victorious generals and their armies were led in procession by the captives and spoils they had taken in war. This was a popular and influential poem series when it was published.[1] Composed over more than twenty years, the poetry is written in terza rima.[2] It consists of twelve chapters (a total of 1959 verses) ordered in six triumphs envisioned by the poet in a dream honoring allegorical figures such as Love, Chastity, Death, and Fame, who vanquish each other in turn. Further triumphs are awarded to Time and Eternity. Composition of the work started in 1351 and the final chapter was last edited on February 12, 1374, a few months before the author's death. The book was produced in many lavish illuminated manuscript versions, and spawned panel paintings for cassoni and the like. The ancient Roman triumph survived the Middle Ages in various forms, and was used as a literary device with the entrance of Beatrice in the Commedia.[3] StructureThe poem is structured in six allegorical triumphs. The triumphs are concatenated, so that the Triumph of Love (over Mankind and even gods) is itself triumphed over by another allegorical force, the Triumph of Chastity. In its turn, Chastity is triumphed over by Death; Death is overcome by Fame; Fame is conquered by Time; and even Time is ultimately overcome by Eternity, the triumph of God over all such worldly concerns. Francesco Pesellino: The first three Triumphs of Love, Chastity and Death, 1450 Two of the triumphal cars, carrying Chastity and Love, from a lavish illuminated manuscript copy (early 16th century). Giacomo Borlone de Buschis: Trionfo e danza della morte, 1485 Zanobi Strozzi: Trionfo della fama, c. 1440-1445 Cristoforo Majorana: Trionfo dell'Eternità, 1490. Four Evangelists draw a cart with a Gnadenstuhl representation of the Trinity above Petrarca's first lines of the poem. Triumphus Cupidinis: Triumph of LoveOne spring day in Valchiusa, the poet falls asleep and dreams that Love, personified as a naked and winged young man armed with a bow, passes by on a fiery triumphal chariot drawn by four white horses. Love is attended by a multitude of his conquests, including illustrious historical, literary, mythological, and biblical figures, as well as ancient and medieval poets and troubadours. Eventually the procession reaches Cyprus, the island where Venus was born. Although only Love is described in the text as riding on a car or chariot, it became normal for illustrators to give them to all the main figures.[4] Triumphus Pudicitie: Triumph of ChastityLove is defeated by Laura and a host of personified virtues such as Honor, Prudence and Modesty, as well as chaste heroines including Lucretia, Penelope, and Dido. Love's captives are freed and Love is bound to a column and chastised. The triumphant celebration culminates in Rome, in the Temple of Patrician Chastity. Triumphus Mortis: Triumph of DeathReturning from the battle, the victorious host encounters a furious woman dressed in black, who reveals a countryside littered with the corpses of once proud people from all times and places, including emperors and popes. This personification of Death plucks a golden hair from Laura's head. Laura dies an idealised death, but returns from heaven to comfort the poet, who asks when they will be reunited in one of the most significant passages of the poem. She replies that he will survive her a long time. Triumphus Famae: Triumph of FameDeath departs and after Death comes Fame. Her appearance is compared to the dawn. She is attended by Scipio and Caesar, and many other figures from Rome's military history, as well as Hannibal, Alexander, Saladin, King Arthur, heroes from Homer's epics, and patriarchs from the Hebrew scriptures. Accompanying these soldiers and generals are the thinkers and orators of Classical Greece and Rome. It has been remarked that for Petrarch, Plato is a greater philosopher than Aristotle, who was preferred by Dante. Triumphus Temporis: Triumph of TimeTime is represented by the sun, chasing the dawn and racing across the sky, jealous and scornful of the fame of mortals. In an elegy on the fickleness of Fame the poet concludes that it will always eventually be followed by oblivion, the "second death". Triumphus Eternitatis: Triumph of EternityPetrarch finds consolation in the almighty God and the prospect of being reunited with Laura in heaven and timeless eternity. Eternity is not represented allegorically. AnalysisTriumphs examines the ideal course of a man from sin to redemption: A theme with roots in medieval culture, being typical of works like Roman de la Rose or the Divine Comedy. Petrarch's work invites comparison with Dante's, from the structural point of view (having adopted Dante's terza rima meter) as well as for its treatment of an allegorical voyage. Triumphs shares and builds on numerous themes of Petrarca's Canzoniere, such as the confrontation of death, as in the sonnet Movesi il vecchierel canuto e bianco ("Grizzled and white the old man leaves"), and the spiritualization of his love for Laura. Critical analysisTriumphs is appreciated for its lyrical achievements and the poet's vivid introspection into his feelings. On the other hand, it has been criticized for the mechanical rigidity of its narrative in contrast to the more natural style of the Canzoniere, and the long enumerations of notable persons which often sap its vitality. This work is also noted by scholar Gertrude Moakley (1905-1998) as being a probable origin for the 21 trump cards of tarot decks.[5] Notes

References

Wikimedia Commons has media related to I Trionfi. |

||||||||||||||