|

Toyouke-hime

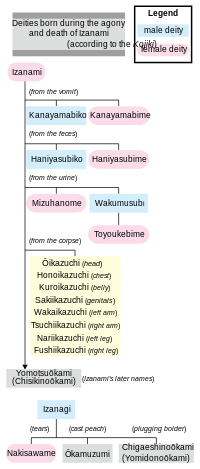

Toyouke-hime is the goddess of agriculture, industry, food,[1] clothing,[1] and houses[1] in the Shinto religion. Originally enshrined in the Tanba region[a] of Japan, she was called to reside at Gekū, Ise Shrine, about 1,500 years ago at the age of Emperor Yūryaku to offer sacred food to Amaterasu Ōmikami, the Sun Goddess.[2]  While popular as Toyouke-Ōhmikami presently,[3] her name has been transcribed using Chinese characters in several manners including Toyouke bime no kami (豊宇気毘売神) in the "Kojiki",[3][4] while there is no entry about her in the "Nihon Shoki". Literally, her name means "Luxuriant-food Princess" kami.[5] Several alternative transcription and names are attributed to this goddess including Toyouke-Okami,[1] Toyouke-Ōmikami, Toyoukebime no kami (豊受気媛神),[6] Toyuuke no kami (登由宇気神),[3][7] Toyouka no Menokami (止与宇可乃売神),[b] Toyuke no Ōkami (等由気太神),[3][8] and Toyohirume (とよひるめ). God and goddess thought to be identical to Toyouke-Ōhmikami are a god [[[Omonoimi no Kami|Ōmonoimi-no-kami]]] Error: {{nihongo}}: transliteration text not Latin script (pos 112) (help) (大物忌神)[c] and a goddess Toyooka hime (豊岡姫).[3][d] There is a separate shrine dedicated to Toyouke's Ara-mitama, or Toyouke-Ōmikami no Ara-mitama (豊受大御神荒魂) called Takanomiya (Takamiya) inside Gekū. She is worshipped at Chōkaisan Ōmonoimi Shrine MythologyIn Kojiki, Toyouke-Ōmikami is described as the granddaughter to Izanami via her father Wakumusubi, and Toyouke was said to settle to Gekū, Ise Shrine at Watarai (度相) after Tenson kōrin when the heavenly deities came down to the earth.[3] In her name Toyouke, "uke" means food, making her the goddess of food and grain,[3] which is said to be the basis on which other kami were equated with and merged into Toyouke as the deity of foodstuffs: Ukemochi (Ōgetsu-hime), Inari Ōkami, and Ukanomitama.[6] The head priest of Toyouke Daijingu submitted "Toyuke Shrine Book of Rituals (止由気宮儀式帳, Toyukegū gishikichō)", or the record of the Ise Grand Shrine to the government in 804,[8] in which it is told that goddess Toyouke originally had come from Tamba.[6] It records that Emperor Yūryaku was told by Amaterasu in his dream that she alone was not able to supply enough food, so that Yūryaku needed to bring Toyuke-no-Ōkami (等由気大神), or the goddess of divine meals, from Hijino Manai in ancient Tanba Province.[3] Stories among various Fudoki indicate the origin of Toyouke: In that of Tango, or "Tango no kuni fudoki", Toyouke-bime (豊宇賀能売命, Toyouke-bime-no-kami)[3] had been bathing with other seven deities at Manai spring on the hilltop of Hiji in Tamba province, when an old couple hid Toyouke's heavenly robe so that she was not able to return to the heavenly world.[3] Toyouke tended to that old couple for over ten years and brewed sake which cured any ailment, but was expelled from the household and wandered to reach and settle at Nagu village as a local deity.[9] The anecdote in the Fudoki of Settsu Province "Settsu-no-kuni fudoki" mentions that Toyouke no megami (止与宇可乃売神)[b] had lived in Tango.[e] Faith and ritualsShe is also thought to be identical to or to have "associated with" Ukemochi.[1] The original locationIn Mineyama Town, Kyōtango, Kyoto prefecture, there is a well Seisuido (清水戸) and a story of the now lost half-moon-shaped rice paddy Tsukinowa den (月の輪田). They are believed to be the site where Toyouke had soaked rice seeds to encourage germination and planted the first rice.[10] The Hinumanai Shrine (比沼麻奈為神社) is mentioned in Engishiki dating back to Heian period, as Taniwa (田庭) literally meaning the Garden of Rice Paddies. That ancient place name is thought to have changed over time to Taba (location of rice paddies), then to Tamba/Tanba (丹波). On the slope of the Kuji Pass, there is a shrine dedicated to Ōkami, as well as Hoi no dan, the ruin of a sacred well Ame no manai of Takamagahara: That well was entered both in Kojiki and Nihonshoki, and was also the highest title given to water bodies. The shrine's auspicious spirit is said to be in the cuboid (盤座, Iwakura), which has been worshiped as Ōmiae-ishi (大饗石). There is a shrine named Moto-Ise Toyouke Daijingu in Ōemachi, Fukuchiyama City[3] to the south of Naiku of Moto-Ise uphill the Funaokayama. Its name literally means former Ise, where the priesthood has been inherited by Kawada clan, the further relative of the Fujiwara clan. Amaterasu and ToyoukeEmperor Sujin appointed imperial daughter Princess Toyosuki-iri (豊鍬入姫命, Toyosuki-iri hime) as a Saiō to serve "as a cane for Amaterasu" to find a new location to reside, and dispatched Toyosuki-iri to travel from present day Nara to neighboring areas. It is said that on the route, several locations hosted the spirit of Amaterasu by building her shrines, while Tango had the first of such shrines among the list of relocation sites. Those shrines honor Amaterasu as their main kami are:

In addition, Toyouke-Ōmikami is worshiped at many branches of Ise shrines called Shinmei shrines, along with Amaterasu,[6] and separate shrines are often built on the property of regular shrines for Toyouke-Ōmikami. There are also Inari shrines where they build altars for Toyouke as well.[6] According to the discipline of Ise Shintō (Watarai Shintō) originated by a priest at Geku named Watarai Ieyuki (度会家行), Toyouke-Ōmikami is recognized as the first divine being which appeared in this world. In their idea, Toyouke is also identical to Ame no minakanushi and Kuni no tokotachi. In this sect of Shinto, Geku, or the shrine of Toyouke-Ōmikami, is treated as ranked higher than Naiku, or the shrine of Amaterasu.[11] Omonoimi Omonoimi no Kami is the God of Chōkaisan Ōmonoimi Shrine and Mount Chokai.[12][13] There are shrines that enshrine Omonoiminokami in various other places in the Tohoku region, including Chōkai gassan ryōsho-gu. [[[Omonoimi no Kami|Ōmonoimi-no-kami]]] Error: {{nihongo}}: transliteration text not Latin script (pos 112) (help) (大物忌神) is considered possibly identical to Toyouke-hime[f][3] He is associated with industrial growth.[14] Every time Mount Chōkai erupted his rank increased.[15][13] See alsoSources

FootnotesNotes

References

Further reading

|

||||||||